|

Apprenticeship

I joined Chubb as a student

apprentice on 4th September 1950, straight from

Wolverhampton Grammar School where I had specialised in

science. My original career ambition had been to go to

Sandhurst as a professional soldier, but I had failed

the medical due to slightly defective vision. The

Wolverhampton Juvenile Employment Bureau were most

helpful and on being advised that part of my reason for

a military career was "to see the world", suggested an

interview with Chubb, who were seeking young men to

train in security engineering and then to join the

Export Department. I was interviewed by Leonard Dunham,

the Sales Director and Leslie Tinkler who doubled his

job as chief estimator with that of apprentice

supervisor. |

A strong room emergency exit door

nearing completion.

Courtesy of the Reverend Bill Enoch. |

Most apprentices started work in

the tool room where they were introduced to engineering

machinery, measuring instruments, and the basics of hand

fitting.

I was extremely fortunate to be

trained by Albert Ling, who was the model maker,

responsible for pre production safes etc, based on the

new drawings.

Our charge hand was a larger than

life character, Ron Brown who later progressed to the

Research Department, where amongst other things, he

handled the explosives used for testing safes, and the

weapons used in testing bullet resisting materials. |

|

At that time we

were working a forty four hour week, and during term

times apprentices were expected to attend Wolverhampton

and Staffordshire Technical College, later Wolverhampton

Polytechnic and then Wolverhampton University, for one

day a week and

as many evening sessions as demanded by our course.

Every six

months, apprentices changed their place of work, so as

to familiarise themselves with the whole factory and its

production.

My next place of

work was the Lock Shop, which consisted of a very large

number of repetition lathes, milling machines etc.,

mainly operated by women under male tool setters, and

the locksmiths benches at which the locksmiths, whose

apprentices underwent a separate course to the safe

works apprentices, produced the whole range of locks |

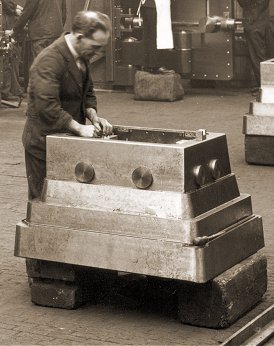

Assembling a strong room

emergency exit

door. Courtesy of the Reverend Bill Enoch. |

George Palmer constructing

a strong room door. Courtesy of

the Reverend Bill Enoch. |

My next area was the Light

Product Works, where fire resisting filing cabinets,

safe deposit lockers, metal deed and cash boxes were

produced.

Initially, I was based with Horace

Ward, the shop foreman, following which I had spells

with Walter Webb, charge hand of the fire resisting

filing cabinet section and then with Bill Stean on the

safe deposit locker section.

Bill had a sideline as a dance

band leader and was a popular figure at local dances. |

|

A spell in the

safe works followed, where I spent a fair amount of time

on the vault door section, although I was encouraged to

look over other sections such as safes, night deposit

traps, the foundry, and heavy machine bays. Most

interesting were the number of relatives who all worked

in the same areas. The Hamlin brothers, who made all the

night deposit safes with their apprentice, Dennis Unit,

who later became a senior manager. The Moore family were

welders and one of my fellow apprentices, also a Moore,

later became a first class welder. The Roberts family

were well represented and over the years were known as

"Old Cock", "Young Cock", "Bantam" and Chick", although

I remember only Chick Roberts. |

| Whilst in the safe works, I was

seen again by Mr. Dunham, during one of his visits, who

enquired whether I still wished to go to the Export

Department. On receiving an affirmative answer he

arranged for me to transfer to the Drawing Office, under

David Tate, the Chief Draughtsman.

I must confess I was not a good

draughtsman but was greatly helped by David Tate who

allowed Ron Swift and myself to carry out many fire

resisting tests on his behalf as he strove to develop

better fire resisting materials. We also made a number

of small prototypes which were most interesting,

particularly when they entered production, based on my

drawings. Ron Swift went on to become a first class

designer and was responsible for many of the later

security features for high grade safes. |

A nearly completed strong room

door. Courtesy of the

Reverend Bill Enoch. |

| For a short period I spent time

with the Time Study department who were responsible for

deciding how long the various items of equipment should

take to make (and therefore the labour cost). This

background was extremely useful in estimating production

time and cost when I joined Export Department, and non

standard items were called for. |

Casting anti-blowpipe alloy

in the early 1950s. Courtesy of the

Reverend Bill Enoch. |

After a further brief spell with

John Jeavons and Charles Grainger, who dealt with the

programming of orders for Chubb products, I was

transferred to Birmingham sales office, then based in

Newhall Street to start learning the basis of selling

Chubb products.

I was extremely fortunate in that

Frank Hall, the sales manager, let me deal with the

showroom and also go out on calls from time to time, and

also assist Peter Dewey, a first class engineer who

dealt with repairs and breakdowns. |

| Peter and I became close friends

and in later years I was able to recommend him for

Overseas Installations, which until then had been

carried out by one or two works engineers, notably, Les

Minshall. Finally in September 1955, my indentures came

to an end and I awaited call up for National Service at

the age of twenty two. |

| Back From

National Service

Following my National Service in the RAF, I resumed work

at Wolverhampton on 1st January, 1956. I was attached to

Mr. Reg Hoye, manager of the Lockworks and given a

refresher course.

I was involved in the early

attempts to manufacture certain locks without all the

hand fitting by locksmiths. This work was carried out at

Leyton, in East London, at the former Hobbs Hart factory

The experiment was not altogether successful but it gave

an insight on what was required to manufacture locks in

this way.

For the final month of my time at

the factory, I was allowed to spend time on the

locksmiths benches, not usually granted to any except

lock apprentices, where I spent time hand fitting locks

and dealing with three and four wheel combination locks.

Finally, in August 1958, I

transferred to London sales to take up my career. |

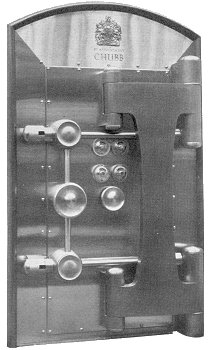

A Chubb

Treasury Vault door. |

| Since joining the Company in

1950, rapid expansion had taken place and in this

period, Chatwood-Milner, itself formed by the

amalgamation of Chatwood and Milner, was taken over.

Hobbs Hart, Josiah Parkes (Union locks), Burgot Alarms,

Rely a Bell, Pyrene, Read and Campbell and others were

acquired to form the rapidly growing security group.

Additionally, a company had been set up in Canada and

the existing operations in Australia and South Africa

expanded. |

|

Another Chubb

Treasury Vault door. |

In addition to this rapid growth,

much development work was taking place in the

construction of safes and vault doors to counter a large

number of burglary attacks.

Many men had been trained in the use

of explosives, cutting equipment and modem tools during

their military service and as much security equipment in

use dated back to the early parts of the twentieth

century, the contest between modern explosives and

cutting equipment, and obsolete safes, was very one

sided. |

| The banks especially, were keenly

aware of the problems posed and instituted large

upgrading programs in their branches, which kept the

security companies, Chubb included, at full stretch.

This period saw the development of the new relocking

devices from the pre-war "static" varieties which could

be beaten by preloading the bolt throwing handle during

an explosive attack, to the final version of the Chubb

"live" re-locker which operated every time the safe was

locked, which together with the handle clutch mechanism,

which disconnected the handle from the mechanism when

locked, effectively closed this avenue of attack. As a

result, explosive attacks became very rare during the

final years of my service. |

| Oxy acetylene metal cutting

equipment had been available to safebreakers since the

late 1800's and Chubb had developed a ferrous based

material which we called A.B.P. (anti blow pipe) which

was practically impervious to attack by oxy acetylene,

and this material which was cast in thick slabs was used

in heavy bankers safes and vault doors.

In the late 1950's however a new

cutting device utilising both the electric arc and

oxygen was produced to cut up the complex alloys which

had been used in the manufacture of military tanks etc.

This was the oxy arc cutter. The first successful attack

using this new tool was carried out on a London bank in

the late 1950's. The perpetrators were caught as the

tool was so new that the manufacturers kept records of

all purchasers. It quickly became obvious that Chubb

A.B.P. could be penetrated by this new weapon and after

much research a material comprising copper and extremely

hard inclusions which Chubb called Anti Arc was

produced. |

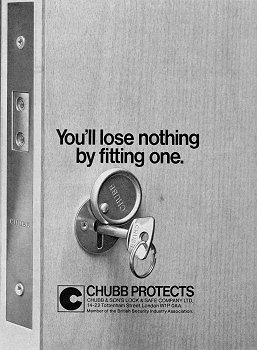

An advert from 1968. |

| This material not only protected

against penetration by oxy arc but also effectively

countered the threat posed by the new tungsten carbide

tipped drills, and the percussion drilling machine which

could bore through most hardened steels and concretes.

A further version of this protective

material was developed using aluminium in lieu of

copper, which was found to be ideal for the protection

of the bodies of safes. Very soon a process was

developed using the aluminium based material, which

enabled the foundry to cast a five sided "bell" on a

heavy steel inner shell, and this system quickly

replaced the old iron based protection used in the

bodies of high grade safes, and remained in use until

the closure of the Wednesfield Road plant.

This form of protection, allied

with a highly sophisticated drill protection, which

covered the vulnerable points of the Chubb "isolator"

bolt locking mechanism, was used in the highest grade

production safe produced at Wolverhampton, "The

Sovereign". |

|

An advert from 1972. |

Until my retirement from the

Company at the end of 1991, no successful attack was

ever recorded on this type of unit. For cheaper

range safes, special concrete protective layers were

developed by the Research Department, which gave

incredibly high levels of protection. These

concretes utilised metal and synthetic fibres to

prevent the shattering, which normal concretes are

subject to, and strict quality control enabled

concretes having extremely high crushing strengths

to be produced. The

early attempts to produce locks more cheaply than by

the traditional hand fitting by locksmiths

eventually bore fruit. Whilst domestic locks (those

for use on company products) were still manufactured

by skilled locksmiths, those sold to the general

public for household and commercial use were

manufactured by a process of extremely accurate

machining which enabled semi skilled fitters to

assemble them without compromising security. |

| The Later Years

The vastly enlarged company fortunes

prospered until the early 1970's when a further addition

to the Chubb group was made. The Gross company

manufactured a range of mechanical cash registers, which

had been extremely popular with many large chain stores.

Unfortunately, insufficient research had been undertaken

to move from mechanical machines to the coming

electronic and computer controlled systems. It became

obvious that unless something could be done to remedy

this situation, Gross would go out of business with the

loss of a large number of jobs.

Naturally this prospect horrified

the Labour government of the day and a high level search

was instituted to seek a rescuer for the ailing company.

Chubb was one of the possible companies approached and

finally it is said after certain government inducements,

Chubb made an offer which was accepted. It quickly

became obvious that Gross was beyond saving, in spite of

large amounts of capital being injected in an attempt to

catch up on the neglected research work.

Finally the cash register business

was closed causing a loss of the capital which had been

denied to the core businesses of the Group. This

financial blow had a severe effect on the stock market

standing of the Chubb Group, as dividends paid to

investors suffered and also reduced funds for the

development of the group. |

| Chubb quickly became a target in

the financial press, as the likely victim of a take over

bid themselves and on many occasions G.E.C. were said to

be the likely predators.

In fact, a senior director assured me

that no take over bid was ever received from G.E.C. or

anyone else, but over a period of time, the drip, drip,

drip of rumour had the desired effect. |

A final view of a

Chubb Treasury Vault door. |

| Racal, headed by Ernest Harrison

was a long time competitor of G.E.C.; in fact it was

reported that there was considerable rivalry between

Arnold Weinstock of G.E.C. and Harrison. Eventually,

Racal launched a bid for Chubb, some said to spite

G.E.C. and as Harrison had something of a cult status in

the City, as a financial wizard, the bid succeeded.

The main casualties were most of

Chubb's senior management, including Lord Hayter, W.E.

Randall, and W.G. Bannochie, all of whom had

considerable service with Chubb and had been successful.

Their replacements under the Racal regime were of a much

lower quality and many employees, including me, could

not understand why Racal had bought the group and for

what purpose. Initially, Chubb were amalgamated into the

Racal Group, but the promised increase in value failed

to occur and eventually Chubb were de-merged from Racal

and set up again as a stock market quoted company.

In the early years of Racal

ownership, many in Chubb, myself included, wondered why

we had been taken over. |

|

An advert from 1974. |

One explanation given to me

whilst on holiday in the West Indies, occurred during a

lunch with two Racal directors, who happened to be

visiting the island where we shared a common agent. The

managing director of our agent, having mentioned my

presence on the island to the Racal men, acted as the

host. During lunch I was quizzed about many aspects of

Chubb and the reaction of Chubb staff to the take over.

I answered to the best of my ability and towards the end

of a very good lunch, one of the Racal men asked if I

had any questions of my own.

I enquired the reason for the take

over when nothing appeared to have changed. "We believed

that you had a very sophisticated electronics

department", I was told. I protested that within the

Group we had alarm and fire companies but really their

work comprised standard electrical fitting rather than

specialised electronics. To this I received the amazing

answer, "Yes, we know that now". |

| It appeared that an error had

been made and it was believed that all towns where a

Chubb Super Centre sticker was displayed - which

indicated a major lock stockist, in fact had an alarm

control centre. I was simply staggered and to this day I

cannot believe that such an elementary mistake could

have occurred. But if it had then at least there was

some sense in the take over.

As time passed and Racal desperately

attempted to provide the "value" which Harrison had

frequently told the City that he could provide, the

accountants resorted to what had become a very popular

measure at this time; discarding staff as a company's

greatest expense, in order to improve the "bottom line".

These voluntary redundancies were

a very fashionable way forward in many businesses at the

time and Chubb were no exception. Gradually, any staff

who might have been considered as excess left and as

further redundancies took place, the staff involved were

vital for production at Wolverhampton. More and more

redundancies were called for until finally in 1991, it

was decided that not only production personnel but also

management and sales must also be "downsized".

In an attempt to save the

positions of some of our younger and very promising

staff, I volunteered to go, on the basis that after

forty one years service, I had very few more years to go

until the official retirement age of sixty five. On

December 31st, 1991 I left the office for the

last time. Unfortunately, this did not save the

prospects for many of our younger staff, who were

dismissed, which I felt to be extremely unfortunate as

they were the future life blood of the company. |

| Shortly after my retirement,

Racal sold the Chubb business to Williams, who owned the

Yale lock company. There had been rumour for some years

that Williams were seeking to acquire Chubb; presumably

to consolidate their lock business.

After a few years however, Williams

decided to break up and sell off their security

business. Fire Alarms and manned security were bought

out by United Technologies, an American concern, whilst

the locks and safes were purchased by Assa Abloy, a

Finnish security organisation, who then sold on the safe

operations to Gunnebo, another Finnish concern.

The Wednesfield Road factory was

closed down and the lock manufacture moved to Willenhall

for Commercial locks, and to a new smaller manufacturing

plant for the high security (prison) locks. |

An advert from 1970. |

|

There was great

sadness amongst many of the former staff, that after

almost one hundred and seventy years, the safe making

skills, in which Chubb had been world leaders, were

finally lost.

It has often

been said that in this modem age, where cash is not so

significant, such skills were no longer required. One

has only to recollect however, that precious metals,

jewels and other valuable commodities still need

protection from theft and that cash is still vitally

necessary for many transactions, to realise that there

is still a place for high grade security products. It is

a pity that the house of Chubb no longer exists to meet

these requirements.

©

D. R. E. Ibbs. August 2007. |

|

Return to

the

Chubb menu |

|