| Little is known about the company’s early years.

It was established in about 1850, the same date as the oldest

building on the site, which presumably was purpose built for the

company. Originally it was called the Crown Nail & Stamping

Company, as was seen on several brass clocking-in disks that

were found at the works in the 1950s.

The advert opposite is from the 1902 Wolverhampton Red Book

and lists many of the company's products. |

|

|

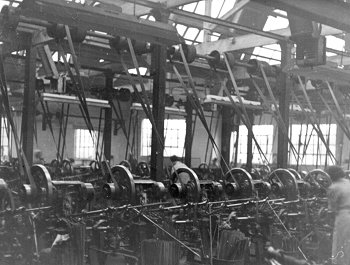

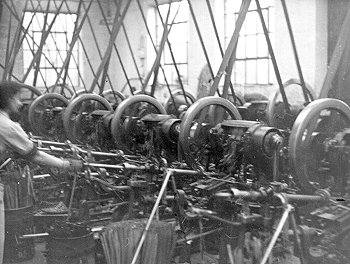

The works in 1871.

|

By 1884 the company was called the Crown Nail

Company, as mentioned in John Steen & Company’s Guide to

Wolverhampton.

Until the early 1950s the company was owned by the Lloyd

Family and it is believed that they were the founders. |

|

In the early years domestic holloware must have been produced on

the site because a number of frying pans, each bearing the name

“The Crown Stamping Company” were used in the works as tack

pans, until the 1950s.

Steen & Company’s directory of 1884 lists

four nail makers in Wolverhampton:

The Crown Nail

Company

The Patent Tip & Horseshoe Company

Messrs. Neve & Company

Danks, Walker & Company.

|

The works in 1901.

|

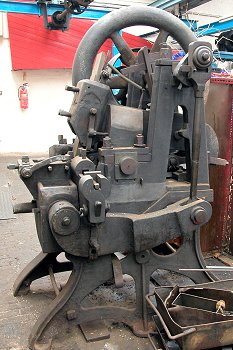

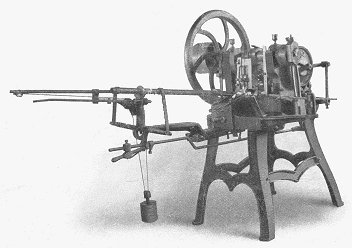

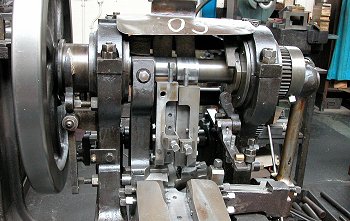

The old Elwell low-down nail machine that

was used in the early years. It still has the original pre 1910

seal to prevent the machine from being used at the time when the

industry was rationalised. The machine must have been in store

for nearly 100 years. |

Two of the companies, The Crown Nail Company and

The Patent Tip & Horseshoe Company were next door neighbours.

Several old machines were kept in store in the Commercial Road

factory, dating from around 1870 but unfortunately carrying no

manufacturer’s name. It has been suggested that they may have

come from The Patent Tip & Horseshoe Company, next door, which

stopped making nails in about 1883.

The Company was run by Paul Bedford Elwell who took out a

patent for nail making machinery in 1876. The patent is for a

low-down cut-nail machine that used a peculiar oscillating feed

arrangement for the steel strip. Instead of turning the strip

over in-between cuts, the strip moved through an arc and each

cut was parallel to the front of the machine.

The oldest machine that was in store at the works used an

identical arrangement and so is likely to be an Elwell machine.

This machine and the one below have been saved by the Black

Country Living Museum and will be on display in a few years

time. |

| In the early years the Crown Nail Company was run

by John Lloyd and it seems that his wife Rose Lloyd took over at

a later date, her signature was found on an old indenture. She

was a rather strict and domineering woman and had two sons, who

later ran the business for many years. The Lloyds were Welsh and

lived at 3 Waterloo Road North before moving to “Hafren”

in Albert Road sometime during the 1930s. |

|

The company was probably founded by John Lloyd and so he must

have been much older than his wife, who lived until the mid

1940s. He had presumably died before 1902 because the family is

listed under the name of Rose Lloyd in the 1902 Wolverhampton

Red Book. The two children, Jack and Harry attended Rugby

School. They were very different, Jack being an extrovert and

Harry an introvert who kept himself to himself.

The two brothers took over the running of the company when

their mother retired. Harry Lloyd ran the office and his brother

Jack, an exceptional engineer, ran the factory. Jack enjoyed

mixing with the workforce but was a strict disciplinarian. Rose

never allowed her sons to marry, they were both dedicated to the

company and spent as much time as they could there. Jack’s only

luxury was his Bentley car, of which he was justifiably proud.

Once a year he would take a week’s holiday and drive off

somewhere. He would always return after about five days because

the factory was his life and he couldn’t stay away.

|

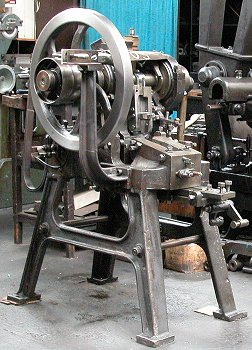

An old machine dating from the 1870s |

| The factory started at the southern end of the

site where the bluing machine used to be. There were even power

presses upstairs on the wooden floor. The company seems to

have been doing well because in the early years of the 20th

century the central building with the Belfast roof was added. |

|

The surviving seal on the Elwell nail

machine. |

Nail production ceased in about 1910 and didn’t start again

until 1986. At the time too many nails were being produced and

in order to protect manufacturers and control prices, a form of

rationalisation was introduced. Many companies, including the

Crown Nail Company were paid a certain amount each year not to

produce nails and so only tacks were made. Seals were placed on

the moving parts of the nail machines to ensure that they were

not used. The Elwell machine that was in store still carries its

seal. |

| Cyril Haydon, who later became Jack's right hand

man, started at the company in 1909 at the age of 14 as a

feeder. Most of the feeders were girls and they earned just

2s.6d a week and were very poor by modern standards, many only

owning a single set of clothes, which was common amongst factory

workers at the time. |

| The feeders were a militant group who insisted

that any new recruit to their ranks must already have a relative

working at the company. Cyril had no relative there, but he did

have a distant relative who ran the pub that was used by the

feeders, and we believe this to have been "The Bradford" in

Commercial Road, where many of the local feeders used to drink.

Cyril's colleagues insisted that he went with them to the pub

and they said to the landlord "Do you know this boy" and he

replied "No". Unfortunately Cyril had not met the landlord

before and so the two relatives did not recognise each other. |

Another view of the Elwell machine showing

the peculiar oscillating feed arrangement. |

|

It was a closed-shop and in order to appease the feeders

Cyril had to leave, otherwise they would have come out on

strike. He left the Crown Nail Company and began an engineering

apprenticeship at Culwell Works in Wolverhampton.

Jack Lloyd must have taken a liking to

Cyril and regretted his departure, because two years later he

asked him to return to the company and join him in the fitting

shop. This was acceptable to the feeders and he returned in 1911

to continue his training under Jack. Cyril was known as Sid at

the works and he and Jack became close friends.

|

| The Elwell machine

and another ancient nail machine in store at the works.

Sadly the machine on the right was scrapped. |

|

The 1914 Wolverhampton Red Book lists two

nail and tack makers:

The Crown Nail

Company, Commercial Road

G. Horobin, 76 Lower Villiers Street

The Crown Nail Company is also listed under

general stampers, and so stamped products were still produced in

1914.

During the First World War the company

supplied all of the tacks that were used to hold the fabric to

the wooden framework of the early military aircraft, which

proved to be extremely lucrative for the Lloyd family. During

the war Cyril Haydon went into the army where he worked in a

field ambulance and was a batman to the Colonel. He didn't enjoy

his new role and when he heard that the army was looking for

engineers for its workshops, he applied and after easily passing

a test became an army engineer. After the war Cyril returned to

the Crown Nail Company and continued to assist Jack Lloyd in the

fitting shop.

|

| The tack machines always ran from overhead line

shafting. Works Manager Ken Farrington remembered one of the old

employees, Frank Edwards describing how it used to be. The

shafting was originally driven by two gas engines, one located

in the old part of the works and another in the fitting shop.

After the second engine’s removal, a slight quarter-circle was

left on the floor where the engine’s flywheel ran. The engines

were replaced by a 50h.p. E.C.C. electric motor that was itself

replaced in 1972. There was also a spare that remained in the

storeroom until the works closed. |

An old view of the tack shop showing the

overhead line shafting that drives the machines. |

|

The 50h.p. motor driving the overhead line

shafting. |

The spare was dated 1926 and so presumably that’s when

the gas engines were replaced. The line shafting proved

to be extremely reliable. It originally used leather belts and

if one broke it would simply follow the pulley and drop to the

floor. In later years the belts were made of nylon and leather,

with a layer of nylon on the outside for strength and a thin

layer of leather on the inside for grip. Older belts were joined

by a riveted steel plate that was eventually replaced by a steel

gripping system called a “clincher”. |

|

If the electric motor failed it would take no more than half a day to exchange

it for the spare. It’s incredible to think that the whole factory was

efficiently running from just one 50h.p. motor. |

|

Expansion

In the 1920s tack production centred around

a number of low-down machines. Towards the end of the decade the

Lloyd brothers decided to expand production and greatly increase

the number of machines. They purchased an American Blanchard and

a British low down machine which were typical of the day, but

Jack was not satisfied with them.

|

|

An American Blanchard machine.

|

He decided to take the best parts from both

machines and with the help of Cyril, use them in a machine of

their own design that would out-perform the commercially

available machines at the time.

With his in mind he fully equipped an enlarged fitting shop,

where he and Cyril designed and built the new tack machines.

Many of the parts were made in-house, but such things as

castings had to be brought-in. |

|

Two types of machine were developed; a standard machine and a

heavy duty machine for longer tacks. Many of the parts including

the tools were fully interchangeable between the machines, which

proved to be very successful. Reliability was foremost in Jack’s

mind. For simplicity they used plain phosphor bronze bearings

(bushes) where possible. All of the bearings in each machine

were of this type except for a pair of big double self-lining

roller bearings, which were brought in to fit the machines. This

technique has worked well because none of the bearings have had

to be replaced for many years, only an occasional machining has

been necessary during normal preventative maintenance.

Jack was extremely pleased with Cyril's contribution in the

development of the new machines and rewarded him with a large

toy car for his young son. They became firm friends and Jack and

Cyril would go together to visit other companies. Jack even gave

Cyril a suit to wear for these occasions. |

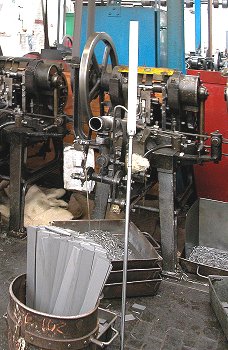

| One of the standard

tack machines that were designed by Jack Lloyd and

Cyril. |

|

|

A large Lloyd tack machine

in the tack shop. Leaning against the rest is the steel strip,

attached to the feed-rod, ready for inserting into the barrel.

The barrel can be seen to the left of the feed rod.

In the foreground is a keg containing a

supply of steel strips. The finished tacks are collected from

the pan on the right. |

| A close-up view of one of

the machines in the fitting shop during repair. On the left is

the flywheel that is attached to the pulley for the overhead

belt. The flywheel is attached to one end of the cam shaft that

operates the tool-holders, which can be seen in the centre of

the photograph. This machine is currently in-store at the Black

Country Living Museum and will be on display in the future. |

|

| The tacks are cut from a strip of steel that’s

hand fed into a long barrel by the operator. Each strip is

clamped to the end of a feed-rod and inserted into the barrel.

It is gravity fed into the machine by a “leather” and a cord

that is attached to a weight. The barrel rotates through 180

degrees before each nail is cut from the strip to minimise

waste. |

|

An old photograph showing the machines in

operation. |

The machines were a great advance on anything else

that was available at the time and between 1931 and 1964 a total

of 104 were built as required.

The smaller machines could produce 280 tacks a minute and

the larger machines 240 tacks a minute.

The first machine went into production on 30th

November, 1931 and was set up by Mr. T. Hitch. |

|

The machines were built as follows:

| Year |

Number Built |

Year |

Number Built |

Year |

Number Built |

| 1931 |

5 |

1938 |

12 |

1950 |

1

|

| 1932 |

8 |

1939 |

6 |

1952 |

4 |

| 1933 |

4 |

1940 |

4 |

1959 |

3 |

| 1934 |

12 |

1946 |

6 |

1960 |

2 |

| 1935 |

6 |

1947 |

2 |

1961 |

3 |

| 1936 |

10 |

1948 |

5 |

|

|

| 1937 |

9 |

1949 |

2 |

|

|

|

| Four of the machines would be overhauled at any

one time. The machines were taken out of service for

preventative maintenance on a five year cycle, irrespective of

whether or not it was needed. The machines were stripped down

and given a full overall before being returned to the tack shop.

The new machines were

installed in rows of ten, with a girl hand-feeding five

machines, so there were two feeders on each row. For every two

feeders there was a spare feeder who would take over if a girl

wanted to leave her machines. |

One of the last hand-feeders was Dawn

Sambrooks, who is seen here at work. |

If one of the feeders wanted

to go to the toilet she couldn’t leave her machines until the

spare feeder took over. This was done to maintain production.

The feeders were paid a production bonus, but not the spare

feeder who was on a lower salary. The bonus was calculated from

the number of tacks produced and was a few pence per 100,000.

When the tacks left the machines they were put into pans and

each girl’s output was weighed twice a week. Each tack was made

to a specific weight to ensure that the customer had a

guaranteed number of tacks per lb.

As well as the feeders there were setters. A setter

would look after 7 to 10 machines and keep a close eye on them,

because in those days the tools had to be taken out and reground

frequently due to the inferior quality of the steel. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Industrial Growth |

|

Return to

the Contents |

|

Proceed to

Shearing & Bluing |

|