The Villiers Engineering Co. Ltd.

1946 onwards

|

After the war demand continued to be very strong and the

company was almost constantly expanding and re-organizing. In 1956

Villiers produced its two millionth engine and duly presented it to the

Science Museum. |

| In 1957 they "absorbed" J. A. Prestwich Industries Ltd.,

makers of the J.A.P. engines. In 1962 the company were claiming

that: "jointly the two companies produce a vast range of two-stroke and

four-stroke petrol engines and four-stroke diesel engines from 1/3rd to

16 bhp.

These are the engines which power many of Britain's

two-stroke motor cycles, scooters and three wheelers and the great

majority of the motor mowers, cultivators, concrete mixers, generating

sets, elevators, pumping sets. etc."

Not only that but the

old standbys continued: "in fifty-eight years [Villiers] have sent

nearly seventy millions [bicycle free wheels] to all parts of the

world".

Not only did the company produce engines but, as they said in

1962: "The Villiers Group offers an extensive service to industry in the

supply of drop forgings, castings, pressings and metal fabrications,

spur, bevel and helical gears, and in the design and manufacture of

Viltool special-purpose machine tools, using the Viltool unit heads and

the 'building block' system of tooling." |

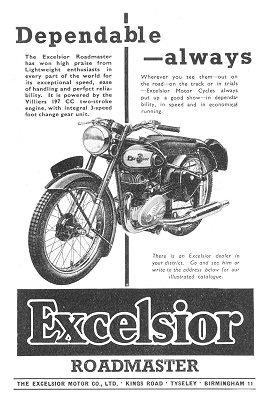

This 1951 Excelsior was fitted with a Villiers

197cc two stroke engine. |

An advert from 1956.

An advert from 1951. |

Overseas the company had subsidiaries in

Australia (Ballarat), New Zealand and Germany and associate companies in

Spain and India.

To give an impression of how widely used Villiers

engines were here is a list, names only, of motorbikes which had

Villiers engines in some or all of their models in the post World

War II period alone: Aberdale, ABJ, AJS, AJW, Ambassador, BAC,

Bond, Bown, Butler, Commander, Corgi, Cotton, Cyc-Auto, DMW, Dot,

Excelsior, Francis-Burnett, Greeves, HJH, James, Mercury, New

Hudson, Norman, OEC, Panther, Radco, Rainbow, Scorpion, Sprite, Sun,

Tandon.

In the early 1960's the company was taken over by

Manganese Bronze Holdings, who also purchased Associated Motor Cycles (A.M.C.)

in 1966.

A.M.C. was formed in 1931 when A.J.S. was purchased by

Matchless. In 1952 A.M.C. acquired Norton Motors Limited who produced

Norton motorcycles. |

|

After A.M.C.'s collapse and take-over in 1966, a

new company called Norton Villiers was formed, which would produce

machines using the Norton name. A new flagship machine was needed to

replace the current ageing models, and so in 1967 the Commando was

developed, just in time for the Earls Court Show.

The first production

machines were completed in April 1968, but there were bending problems

with the frame and so a new frame was developed, and introduced in

January 1969. The original model, now called the 'Fastback' was joined

by the 'S Type' which had a high level left-side exhaust and a 2.5

gallon petrol tank.

Initially

the engines were produced in Wolverhampton, the frames in Manchester and

the components were assembled at Burrage Grove, Plumstead. The Plumstead

works were subject to a Greater London Council compulsory purchase

order, late in 1968 and closed in the following July. |

An advert from 1953. |

|

After a Government subsidy, an assembly line

was set up in a factory at North Way, Andover, with the Test

Department in an aircraft hanger on nearby Thruxton Airfield.

Manufacturing also took place in Wolverhampton,

where about 80 complete machines were produced each week. Components

and complete engines and gearboxes were also shipped overnight, from

Wolverhampton to the Andover assembly line.

The police were showing a lot of interest in

the Commando and so Neale Shilton was recruited from Triumph to

produce a Commando to police specifications. The end result was the

'Interpol' machine, which sold in good numbers to police forces,

both at home and abroad. The machine was powered by a 750 c.c. O.H.V.

engine and included panniers, top box, fairing, and had fittings for

a radio and auxiliary equipment.

Right

from the beginning the Commando took part in racing events, and

after its win in the 1969 Hutchinson 100 and a second place in the

Production T.T., the company decided to produce a racing model. This

led to the development of the successful 750 c.c. overhead valve

'Production Racer'. It featured a tuned engine, front disk brake and

was finished in bright yellow, which led to the machine being known

as the 'Yellow Peril'. |

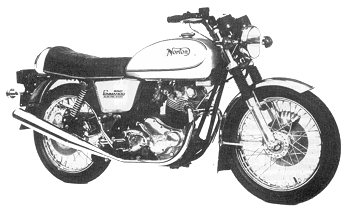

The Norton Interstate. Courtesy of the late Jim Boulton. |

A new version of the 'S Type' was introduced in

March 1970, called the 'Roadster'. It had a 750 c.c. O.H.V. engine and a

low-level exhaust, with upward angled silencers and reverse cones. The

model 'S' was discontinued in June.

September

1970 saw the introduction of the 'Fastback MK. 2', which was soon

replaced by the Mk.3. It had alloy levers and modified stands and chain

guards. |

|

The ‘Street Scrambler’ and the ‘Hi Rider’ were

launched in May 1971 and the ‘Fastback Long Range’ with a larger petrol

tank, was launched in July. January 1972 saw the appearance of the ‘Mk.4

Fastback’, an updated ‘Roadster’ and the ‘750 Interstate’, with its high

performance ‘Combat’ engine. The ‘Combat’ could deliver 65 b.h.p. at

6500 r.p.m. with a 10 to 1 compression ratio. Unfortunately the engine

proved to be extremely unreliable, main bearing failures were common and

pistons tended to break off at a slot, under the oil control ring. These

problems gave the company a bad reputation, which wasn’t helped by the

fact that the ‘Commando’ suffered from quality control problems which

were well covered in the motorcycling press.

By the middle of 1972 the BSA-Triumph group were in

serious financial trouble and the Government decided to bail the company

out with a financial rescue package, providing it would agree to merge

with Norton Villiers. This led to the formation of Norton Villiers

Triumph Manufacturing Limited, but the new company got off to a shaky

start.

In January

1973 the ‘Mk.5 Fastback’ was launched and the ‘Long Range’ discontinued.

In April the ‘Roadster’, ‘Hi Rider’ and the ‘Interstate’ all began to

use a new 828 c.c. engine. Development work also began on a 500 c.c.

twin, stepped piston engine, with a monocoque pressed steel frame. The

new engine, called the ‘Wulf’, was dropped in favour of developing the

rotary Wankel type engine that had been inherited from BSA. |

|

Things

went well that year for the Norton racing team. Peter Williams won the

1973 Formula 750 T.T. and Mick Grant came in second. Unfortunately the

company itself was in deep financial trouble and redundancy notices were

issued at Andover, which was followed by a sit-in at the works.

The

situation continued to deteriorate in 1974 and came to a head in June

when the Government withdrew its subsidy. |

The 750 Commando. Courtesy of the late Jim Boulton. |

|

There was a general election and luckily the

incoming Labour Government restored the subsidy. The company decided to

close two of its sites and concentrate production at Wolverhampton and

Small Heath. This caused a lot of industrial unrest at Meriden, and

resulted in a workers’ sit in, which stopped production at Small Heath.

By the end of the year the company had lost over 3 million pounds.

Even during these hard times the company still

managed to produce new models. 1974 saw the release of the ‘828

Roadster’, the ‘Mk.2 Hi Rider’, the ‘JPN Replica’ and the ‘Mk.2a

Interstate’. Only two of these were to continue in production the

following year. Early in 1975 the company reduced its range of models to

just two machines, the ‘Mk.3 Interstate’ and the ‘Roadster’. Both

machines were improved by the fitting of an electric starter, a left

side gear change, right foot brake and rear disk brake.

Things went from bad to worse in July when the

Industry Minister recalled a loan for 4 million pounds and refused to

renew the company’s export credits. The company then went into

receivership and redundancies were announced for all of the staff at the

various sites. At Wolverhampton an action committee was formed in an

effort to continue production and develop the ‘Wulf’ engine. The works

were picketed and a prototype machine called the ‘Norton 76’ was

produced. This came to nothing as the Wolverhampton works never

reopened. It was a sad end to such an important company, and a bitter

one. Many of the local workers never received the money that was owed to

them.

Norton

Villiers Triumph managed to survive when the Government stepped in to

save part of the company, but unfortunately this did not include the

Wolverhampton factory. The British motor cycle industry was in its death

throes. The market for British machines disappeared, there was not

enough demand to maintain the factory. With a strange burst of

enthusiasm the company bought the gates from the now demolished Tong

Castle and erected them at the works entrance in Marston Road. It was a

last gesture. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to World

War Two |

|

Return to the

Beginning |

|

Proceed to

Motorcycle Engines |

|