|

Recipe Books

Recipe books became part of the popular press

thanks to Isabella Mary Beeton’s “Book of Household Management”

which was first published in 1861. For many years it was the

best selling book on the topic and became a “must” for the

well-appointed Victorian kitchen. There are chapters on

preparing all kinds of food and drinks; food for invalids;

domestic servants; the rearing and management of children;

diseases of infancy and childhood; and the doctor. The book is

over 1,000 pages long and offers advice on such diverse subjects

as etiquette, animal husbandry, poisons and fashion. It is well

illustrated with coloured engravings on nearly every page and

was the first book to lay recipes out in the form that we still

use today.

Isabella Beeton was born in Cheapside, London in 1836 to

Benjamin and Elizabeth Mayson and educated at Heidelberg. She

became an accomplished pianist and married Samuel Orchard Beeton

in 1856. |

| Her famous book was written when she was only 22

years old, but her life was filled with tragedy. Their first child

Samuel died in September 1859 and soon afterwards the couple had a

second child also called Samuel. The winter of 1858 was very severe

and Isabella opened a soup kitchen at her home for the poor children

of Hatch End and Pinner. She had a very short life, dying from

puerperal fever at the age of 28.

Although there were other Victorian recipe books, Mrs. Beeton’s

is the one we all remember, giving the middle-class housewife

and her staff much of the information required to run the

“perfect home”. Cooks could experiment like never before using

many of the new ingredients that appeared in the shops from all

over the Empire. The newly built railways enabled fresh food to

be quickly and cheaply transported over long distances and new

techniques such as canning and bottling were developed for

preserving food. In the 1860s cheap ice was available and

refrigerated transport appeared in the 1880s. |

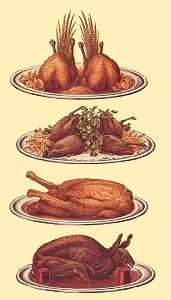

| Illustrations from

Mrs. Beeton's book. |

|

| The following is a brief description of a typical

Victorian middle-class household where the early recipe books would

be found. It is worth noting that many working-class families and

poorer families would not even have been able to afford to buy a

recipe book let alone some many the ingredients mentioned within. |

|

Victorian and

Edwardian Kitchens

What were kitchens like when Mrs. Beeton’s

book first appeared? They were certainly very different from

what we know today. Victorian families were often large with

maybe 10 children and several servants to feed and look after.

The kitchen was a hive of activity with a lot of work to be

done. |

|

Cooking was often done by the cook rather

than the lady of the house on a cast iron kitchen range, which

had a raised open fire in the centre with an oven on either

side. A cooking pot could be hung over the fire on a hook and

items could be roasted in front of the fire on a spit, which was

turned by hand or even operated by a clockwork motor. A large

tin would be placed underneath to catch the fat. The range was

also used for heating water. A boiler at the back provided all

of the hot water for cooking, washing and household needs. Gas

ovens slowly replaced the kitchen range. Early versions were

exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 but they were slow to

catch-on. People were afraid of gas explosions and eating food

that had been exposed to harmful gas fumes. Gas cookers didn’t

sell in large numbers until the 1890s when they gradually

replaced most of the old solid fuel ranges in middle-class

homes. In many working-class homes it was a different story,

ranges continued in use until well into the twentieth century.

A large wooden table would be used as the

work surface and would be carefully scrubbed-down between each

use. There would be a large wooden dresser with open shelves for

crockery and drawers for table linen and cutlery, and possibly a

square or rectangular “Belfast” sink.

Gas lighting would be installed in the more

affluent homes, others would have used oil lamps. Walls were

often finished with white or distempered plaster, or even

varnished paper for ease of cleaning. Glazed wall tiles became

more affordable in the 1890s and they became very popular being

so easy to clean. Windows were very high to provide efficient

ventilation and floors were made of stone slabs or unglazed

tiles.

Food was stored in the pantry or larder, a

room off the kitchen that was sometimes fitted with slate or

marble shelves to help keep the food cool. Such things as

washing-up, vegetable preparation and laundry work were done in

the scullery. Even smaller houses had a scullery and often it

would contain the only sink in the house. It wasn’t until the

twentieth century that kitchen sinks became popular.

The kitchen was a busy place with so many

mouths to feed thanks to the large families that were

commonplace at the time. Labour saving devices were a necessity

and all kinds of aids were developed. There were knife

sharpeners; lemon graters; lemon squeezers; parsley choppers;

sugar snippers to cut pieces of sugar from a slab; potato

peelers; mincers; and even hand-operated food processors. The

electric kettle was invented by Crompton and Company in 1891 and

temperature controlled ovens were developed that used a

complicated system of flues and metal plates. The cook could now

prepare the more complex meals that had previously only been

enjoyed by the wealthy. |

|

Cleaning the kitchen

In Victorian times few proprietary cleaning

agents were available. Recipe books sometimes contained formulas

for making your own. Knives and utensils could be cleaned with

abrasives such as emery powder, and rust was removed with a

mixture of turpentine, camphor and emery powder. Glass could be

cleaned with methylated spirit on a cloth and then polished with

a leather, and brass and tin could be cleaned using a mixture of

rape oil and rottenstone. Silver could be polished using a

mixture of chalk, ammonia, alcohol and water. Drains were

disinfected with chloride of lime and all animal and food refuse

was burned.

Washing powders are a modern invention, in

those days a blue bag was used instead. We all take furniture

polish for granted today whereas in Victorian times this was

often made from a mixture of beeswax, white wax, turpentine and

white soap. |

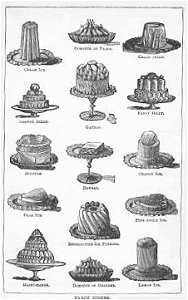

Another illustration

from Mrs.

Beeton's book. |

|

|

Domestic Servants

Domestic servants were commonplace in

middle-class homes, working-class families relied upon their

children to do much of the work.

Smaller houses had only one servant, a maid

of all work. She did all of the household work including

cooking, cleaning, washing, shopping, and lighting and tending

to the coal fires. She lived in the house and possibly only had

one week’s holiday a year.

A larger house would have had several

servants. There would have been a cook who prepared the meals

for both the family and servants, a scullery maid who did all of

the dirty jobs such as washing up, doing the laundry, scrubbing

floors and preparing coal fires. There would also be one or more

housemaids who looked after the family and did all of the

general housework.

Mrs. Beeton was by no means the first lady to

produce a recipe book but she did inspire many others to do the

same, aided by the Victorian’s emphasis on self-improvement and

the growth of education.

Old recipes are evocative of the past and are

fun to follow and try out, giving us an opportunity to sample

some of our ancestor's favourite food.

|

Return to the

list of recipes |

|

|