|

Mill Street Depot

Wolverhampton High Level railway station was built

as part of a joint venture between the Shrewsbury &

Birmingham Railway, and the London & North Western

Railway. The station was originally called

Wolverhampton General Station, and later renamed

'Queen Street' Station in 1853. The station

buildings were designed by Edward Banks, the

Shrewsbury & Birmingham Railway's architect.

The site also included a purpose-built goods

station, that was jointly owned by the two

companies, and presumably designed by Edward Banks.

It became known as Mill Street Depot, and had

warehouses and canal basins. The railway to

Birmingham, known as the Stour Valley Line, opened

on 24th June, 1852 in the middle of a dispute

between the two railway companies.

After the dispute, the Stour Valley Line was

operated solely by the London and North Western

Railway, who purchased the Shrewsbury and

Birmingham Railway's half share in the goods depot in

September, 1859.

|

The location of Mill Street Depot.

Mill Street Goods Depot as it is today,

showing the mixture of S& B and L.N.W.R. buildings.

| The depot operated in the London and North

Western Railway's usual efficient manner. Work at the depot was

extremely methodical, just like in a modern Royal

Mail sorting office. Packages of all shapes and

sizes arrived from all over the country and every

one had to be accurately sorted and sent to the

correct destination. Similarly parcels and all kinds

of manufactured goods that were sent by rail from

Wolverhampton had to be accurately sorted and

dispatched on the correct train. The London and

North Western Railway buildings are of the company's

usual pattern, and were designed at Crewe. All of

the components including the bricks were produced at

Crewe and would have been delivered to Wolverhampton

as a kind of kit, just like buying a garden shed

today from a D.I.Y. store.

Inside there would have been platforms fitted

with standard types of “North Western” cranes and

hydraulic lifts, some of which could lift loads of

up to 14 tons. There would have been warehouse

facilities for the temporary storage of inwards and

outwards goods, and provisions for the storage of

perishable items such as food.

The L.N.W.R. moved vast amounts of goods, many of

which were for the railway’s own use. Being the

largest railway company in the country it used an

enormous amount of consumables which all had to be

transported around the network. In 1913 no less than

57.5 million tons of freight were transported

throughout the system.

In the early years of the 20th century Mill Street

Goods Depot was handling around 50,000 tons of goods

annually.

Wolverhampton became the headquarters of the L.N.W.R.

South Staffordshire and East Worcestershire Goods

District, with offices in the Queens Building. Goods

traffic greatly increased with the building of many

private sidings. In 1887 Thomas Mitchelhill became

District Goods Manager. |

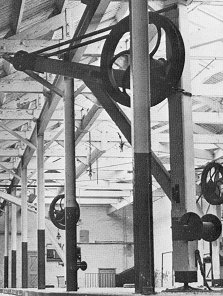

The hydraulic engine house that is on the opposite

side of Corn Hill to the depot. This produced the

pressurised hydraulic fluid for the cranes and lifts

that was piped into the depot via Corn Hill bridge.

|

|

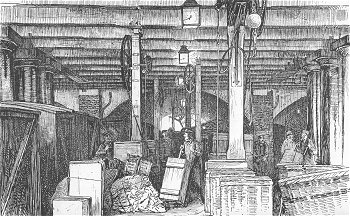

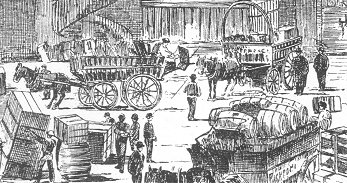

A contemporary drawing showing goods being unloaded from an L.N.W.R. train. Goods to be transported were loaded onto wagons and this was an art form in itself. |

It was as expensive

to transport an empty wagon as one that was full, and

so efficient use of wagon space was essential. Heavy

articles could not be placed on top of fragile ones

and care had to be taken to avoid spillage or

contamination from one package to another.

Some

articles were moved at the owner’s risk, whereas

others were moved at the company’s risk, and so

errors could be costly. |

| Wagons were loaded and unloaded by gangs of men

consisting of porters, loaders, checkers, yardsmen

and warehousemen. A typical gang consisted of five

men, but this varied with fluctuating levels of

traffic. Gangs worked a 72 hour week, which included

12 hours for meal breaks. Sometimes alternate day

and night shifts were required and salaries were

boosted by a bonus system based on the weight of

goods moved during each shift. |

An L.N.W.R. 10 ton goods van. |

|

A loaded and sheeted L.M.S. wagon. |

There were many special wagons for delivering

different types of goods. Initially wagons were open

topped with either high or low sides. One of the

most profitable commodities that railways delivered

was coal. This was mined in huge quantities, and in

the days of poor roads and primitive vehicles, the

only efficient and cheap way of delivery was by

rail, and coal wagons were developed for the

purpose. There were mineral wagons, coke wagons,

low-sided open wagons, and eventually covered goods

vans. |

| Specialised vans were developed for transporting

such things as cattle and butter, refrigerated vans

held frozen food, fish or meat. Some fruit vans

were fitted with steam heaters to help ripen

bananas. Arriving wagons were transported to the

loading platform or the yard in readiness for the

transfer of their contents to road vehicles for the

final part of the journey. The platform was

accessible by an open arch, so that when necessary,

road vehicles could be backed up to it and easily

loaded. Invoices for the incoming goods were

collected and inspected. Each included a description

of the goods, their destination, weight and

particulars of the charges. These were passed to the

delivery office where details were entered into a

book and stamped with an identity number. The

arrival time was noted and the charges were checked.

The Marking Clerk then entered the details of where

the item would be stacked on the platform or sorting

bank, in readiness for collection. |

A typical L.N.W.R. crane. |

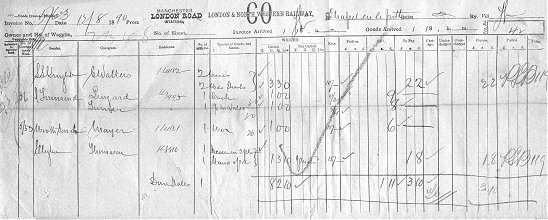

An L.N.W.R. goods invoice issued at Manchester

London Road Station. It is dated 13th August 1890

and is for buckets, shovels, a box, and a stand. It

includes details of the goods, their weight and the

charges including payment for the porters.

|

|

Each platform was divided into sections that were

marked by letters and numbers painted on the roof

supporting columns, along its length.

The invoice was

then passed on to a clerk who produced a delivery

sheet for the driver of the road vehicle. |

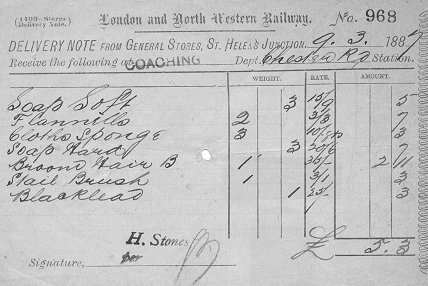

A delivery note issued by the General Stores at St.

Helens Junction on 9th March 1887 for soap,

flannels, sponges, brushes and black lead.

|

| When the paperwork was complete the invoice was

returned to the platform where a gang of men would

unload the wagons and position the goods at

appropriate places on the platform, using hand

trucks and sack trucks. There was also space for

goods that had arrived without an invoice, which

sometimes arrived late due to delays in the paperwork. If

the unloaded goods were to be left for any length of

time on the platform a warehouseman might be on hand

to prevent pilfering. |

A typical "North Western"

goods yard; a veritable hive of activity. |

The loading of the goods onto road

vehicles for the final part of the journey was in

the hands of the Delivery Foreman, who examined the

paperwork and organised the porters during the

operation.

In the early days the road vehicles would have

consisted of a horse and cart that was driven by a

cartage man, known locally as a carter, carman,

drayman or lorryman. |

| They were slowly replaced by lorries, which were

handsomely painted in the company’s livery; horses

however continued in use for many years.

After emptying, the wagons were transferred to

another platform in readiness to receive outward

going goods, which arrived on loaded road vehicles.

These vehicles were stopped at the weighbridge

office, and the consignment notes were stamped with

an official stamp for authenticity. |

Mill Street Depot yard in 1908. In the foreground is

a wagon turntable, several of which were in the

yard. |

Some of the road vehicles that were used in

L.M.S.

days. |

After inspection they backed-up to the outward goods

platform. The Unloading Foreman then inspected the

consignment notes and handed them to the checkers

and unloading gangs, who unloaded the goods onto the

platform, and checked them against the entries on the

notes.

Finally the goods were weighed and placed in

appropriate positions on the platform, corresponding

to their final destination. |

| The empty wagons were filled by a loading gang,

consisting of a checker, a loader, a caller-off and

several porters. When loaded they were sheeted,

labelled and taken to a siding to await their

locomotive. The consignment notes were taken to the

shipping office where the clerks recorded the

details, and made out the invoices that were handed

to the brakeman who was in charge of the outgoing

train. If they were not ready in time for the

departing goods train, they were sent by fast

passenger train to their destination. |

An L.N.W.R. "G2" class goods locomotive at Willesden

Shed. These were a common sight throughout the

network and many continued in use until almost the

end of steam. |

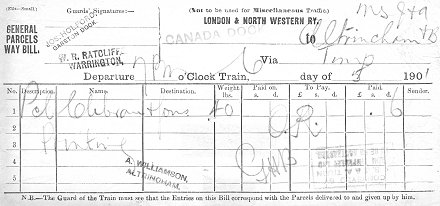

An L.N.W.R. Way Bill issued at Canada Dock.

| On 1st January, 1923 the London & North Western

Railway became part of the London Midland and

Scottish Railway, known as the L.M.S. which

continued to run the goods depot until the railways

were nationalised on 1st January, 1948. From 1959

the goods depot was run from Birmingham as a result

of the introduction of the Midland Freight Traffic

Plan. |

Some of the L.M.S. goods staff in the early 1930s.

Back row

Next row

Next row

Next row

Front row |

L to R: ?,?, Harry Newman, ?,?,?

L to R: ?,?, Powell, ?, Jimmy Cuthbertson, Dunton, ?, Bob Clayton, ?

L to R: ?, Harry Ubbotson, ?, Joe Edwards,

D. Pinney, ?,?, Perks, Burton, Mantle

L to R: ?, Harry Johnson, ?, Fred

Humphreys, ?,?, Perrins, Jack Mason, ?,?,?,?, Thomas

L to R: ?,?,?,?,?,?,?, Edith Ubbotson,

?,?,?

|

| This has been a brief description of the goods

depot, and the daily procedures that were rigidly

adhered-to, so as to ensure that all of the goods

were transported to their correct destination in the

most efficient manner. As time progressed road

transport slowly took over and the quantity of goods

transported by rail fell dramatically.

There was a

time when nearly every railway station had its own

goods depot. Some were large and others small, but

they played an important role in earning revenue for

the railway company. Most of the old goods depots

are now long-gone, and we are lucky to still have

such an excellent example standing in Wolverhampton,

and still in use today. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|