|

The

growth of Japanning

Corrosion-proof, and heat resistant

household items made of metal became a practicality in

the late 17th century with the invention of the rolling

mill to produce thin sheet iron, and the development of

rust-proof coatings. The first of these, tin plating,

was originally developed in Germany, from where tin

plate was exported to the United Kingdom, until the War

of the Austrian Succession in 1738, after which it was

manufactured here.

The second invention, japanning,

consisted of the application of a varnish, which when

heated provided an extremely tough and durable black

finish. All kinds of items in every day use were

produced using these processes, including candlesticks,

coal boxes, coal scuttles, trays, coffee pots, and tea

pots. When the varnish was heated, after application, it

provided an ideal surface for decoration.

Japanning began in Pontypool in the

late 17th century when Thomas Allgood developed his

corrosion resistant oil varnish, made from linseed oil,

burnt umber, and the coal by-product, asphaltum. Items

varnished in this way became known as Pontypool ware. |

An example of decorated japanware,

a papier mache collection plate. Courtesy of Lawson

Cartwright, |

Japanned goods were being produced

in Bilston as early as 1719 by Joseph Allen and Samuel

Stone, and also in Birmingham, where in 1740 a japanning

works was set up to produce trays. The rich decoration

that appeared on many locally japanned items must have

owed a lot to the Bilston enamelling industry, and its

highly skilled enamellers.

Around the middle of the 18th

century, japanned goods were being produced in

Wolverhampton, which had an abundance of skilled metal

workers. It soon became an important manufacturing

centre for the industry.

Sketchley & Adams’ Directory of

Wolverhampton for 1770 lists 8 japanners. Pigot &

Company’s Directory of 1842 lists 16, including some

notable manufacturers such as Henry Fearncombe, Edward

Perry, Loveridge & Shoolbred, and Benjamin Walton at

the Old Hall, which became the cradle of the local industry. |

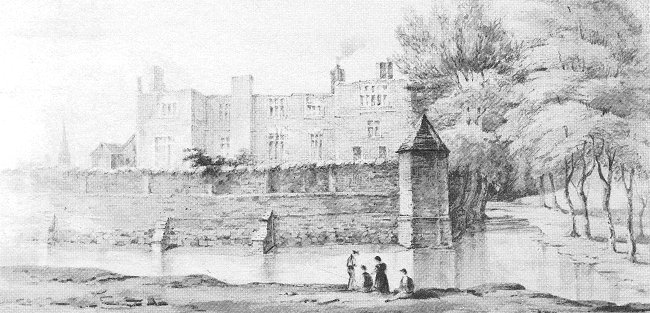

A drawing of the Old Hall and moat. From a 1907 edition of the

Wolverhampton Journal.

| The Old Hall was originally a manor house with a

moat, which belonged to the wealthy Leveson family, who

made a fortune from the wool trade, and owned much of

the land, both in Wolverhampton and the surrounding

area.

After the Levesons had departed, the hall came into

the possession of the Turton family, who owned, and

occupied the building for many years. As a result it was

often called ‘Turton’s Hall’. |

The Old Hall during demolition in

1883. From the collection at Bantock House. |

|

After being empty for some time, it

was rented on a long lease to William and Obediah Ryton,

who were tin plate workers, manufacturing Pontypool

ware. They lived in part of the building, and converted

what remained into workshops. Their business became

extremely successful, and for a while the local

japanning industry was centred on the Old Hall. One

famous apprentice there was Edward Bird, R.A. who became

a well known artist, whose paintings sold for large sums

of money.

After Obediah Ryton’s death, his

brother William continued in business at the Old Hall

with a new partner, Benjamin Walton. They specialised in

new forms of decoration, and paper tea trays, which were

sought after by the wealthy, and sold from £5 to £10

each.

Another successful local japanner who started his career

at the Old Hall was Edward Perry. He built-up a large

business at Jeddo Works in Paul Street, where much of

what follows took place. |

|

|

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed to

unrest and the strike |

|