|

The

strike at Jeddo Works

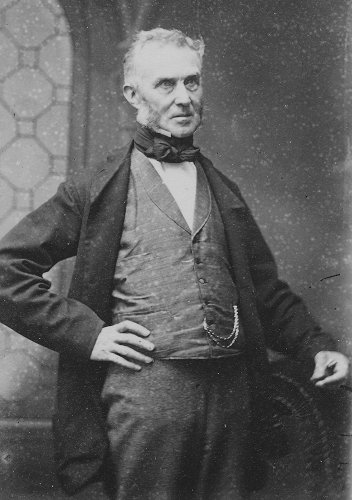

Edward Perry was clearly a

strong-willed man who felt that he could stand up to the

forces of adversity. William Highfield Jones described

him as follows:

Edward Perry was of medium height,

a thin wiry man, with a fidgety manner and of a restless

disposition. He had dark piercing eyes, and an incisive

way of speaking. His promptitude in emergencies was

remarkable, and he proved himself to be a man of great

determination. Mr. Perry had a good knowledge of the

rights of capital and labour, and especially of the laws

relating to conspiracy, and he felt sure the ignorance,

and the enthusiasm of the working men would give him an

advantage which he would be prompt to take.

The two London delegates, Peel and

Green organised the strike, and used the Swan with Two

Necks pub at the top of Paul Street as a base. They

formed a strike committee to meet daily in the pub, and

appointed 5 workers as committee members, each being

paid 4 shillings and sixpence a day, and an extra

sixpence for drink. The members were: George Duffield,

John Gaunt, Charles Piatt, Henry Rowland, and Thomas

Woodnorth. |

Edward Perry. From "The Mayors of

Wolverhampton" by John Jones. |

When the strike began, Perry

advertised for men to replace those on strike. In

response the union circulated posters warning men not to

work for Perry, who was described as a tyrant who paid

half the going rate.

The committee kept an eye on the

factory through the windows of the pub, and sent groups

of men to the entrance gate to intimidate those still at

work. They also attempted to prevent anyone entering the

factory who was seeking work. The strikers shouted at

the workmen as they came to and from work, calling them

‘blacklegs’, ‘rats’ etc. and threw dead rats at them.

They also hung dead rats around the works entrance.

Not satisfied with their actions,

the committee managed to convince some of the older

apprentices to stay away, and sent them to other towns

where they were looked after. They also allured some of

the workers, who were on a long term contract with

Perry, into the pub, got them drunk, and conveyed them

to the railway station where they were put on trains and

sent to distant parts. They also gave money to the

families of the strikers.

This continued for 8 months, after which most of

Perry’s workers were on strike. He was unable to fulfil

any outstanding orders, but being the man he was, he had

spies everywhere, who kept him informed of the actions

of the strike committee. |

| One of them was his nephew George Winn, who

sympathised, and drank with the strikers to gain their

confidence. He discovered where some of the hired men

who had been spirited away by the committee were living.

On hearing of this, Perry instantly sent warrants for

their apprehension. Some were sent to prison, and others

went back to work after paying costs. One of them had

caught a severe cold whilst away, and on return to

Wolverhampton he died.

Things Worsen |

|

The trade association attempted to

intimidate Edward Perry even further by sending him

anonymous letters. In them he was described as a

murderer, and threatened with his life.

One night a large chalk drawing of

a coffin appeared in front of the works, bearing the

words “E. Perry, prepare to meet thy God”.

Comical verses were written about

him and sung in the streets of the town. Out of the 59

hired workmen still at the factory, 18 had been spirited

away by the committee, which was aided by delegates from

London, who actively helped in getting the workmen away. |

| The location of

Jeddo Works. From Joseph Bridgen’s map of

1850. |

|

|

Perry then attempted to attract

some of his old hands who were working at the Old Hall.

He offered them good wages, and a bonus of five pounds

to return. When several of them returned, it incensed

the other workers at the Old Hall, who had each been

paying four shillings a week to support the strike.

When the next man was about to

leave and return to Perry, his colleagues decided to get

their own back. His name was Tom Jones. They waited for

him to receive his wages, then formed a circle around

him, and treated him in a barbaric manner, shouting,

booing, and beating iron pans. As he managed to make his

escape, the police closed the street and forced the howling

mob back into the works.

The

European Connection

In an attempt to defeat the strike,

Perry sent his nephews George Winn, and his brother

Alfred to France to hire thirty tinmen. Alfred could

speak French and so acted as the interpreter. Twenty

eight men signed an agreement to work for Perry for

twelve months and soon arrived at Wolverhampton railway

station where they were met by Edward Perry and his

solicitor Henry Underhill. On their march to the works

they were tormented and intimidated by the mob. The poor

Frenchmen were terrified by the ordeal, made worse

because they could not understand a word of English.

Perry provided lodgings for them

near the works. The strike committee were determined to

convince them to leave, and paid an old French soldier

named Mayeurs, to talk to them. He soon convinced them

to return home, informing them that the union would give

a handsome present to each man, and pay their fare home.

They were in a frightening situation and only too happy

to leave. Had they known of the strike beforehand, they

would certainly not have come.

The committee was jubilant with

their success. They formed a procession, and paraded

through the streets with the Frenchmen as they made

their way to the railway station. Flags and banners were

waved, and a brass band played:

“See the conquering hero comes,

Blow the trumpet, beat the drums.” |

A view of Paul Street in 2001.

Jeddo Works was at the far end of the street on the

left, and the Swan With Two Necks was in the foreground

on the right, where the tree is standing. |

The committee and strikers were in ecstasy, they

thought they had won their fight, but Edward Perry was

made of sterner stuff.

He quickly arranged for his nephews to go to Germany in

secret and return with 30 German tinmen. They placed

adverts in German newspapers and soon engaged 30 men to

work for 12 months, along with an interpreter. While

this was happening, Perry organised sleeping quarters

for them at the works, and on their arrival in

Wolverhampton, secretly conveyed them in closed

carriages. At the factory the gates were closed, and all

their needs were catered for, so that no outside

communication with the strikers was possible. |

|

The public meeting

The strike committee, who had no

idea of what was happening, were furious. They were

powerless to intervene, and were anxious because the

reserve fund was exhausted. They stepped-up their

campaign against Perry’s workmen, intimidating and

ill-treating them worse than ever. One of them, John

Briggs, was knocked down and assaulted in a public

house. The man who committed the offence was brought

before the magistrates and fined 40 shillings and costs.

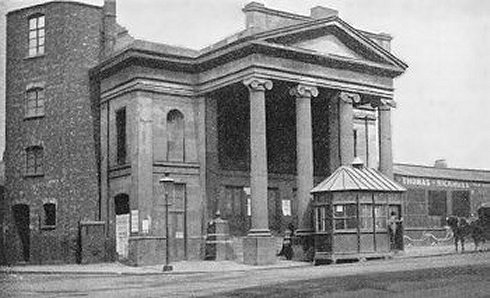

The strike committee felt that they

were loosing public sympathy and so called a mass

meeting at the Theatre Royal in Cleveland Road. They

placed large numbers of posters around the town,

inviting workmen to come along to assist them in

fighting the tyranny of the employers.

The meeting, held on Tuesday, 22nd October, 1850 was presided

over by Samuel Griffiths, a businessman, merchant and

factor, who drifted into the iron trade, and came to

intimately know the industry. Several people spoke to

the audience, including Mr. A Fleming, treasurer of the

union, Mr. Peel, union secretary, Mr. Bartlett,

solicitor of the strike committee, and Mr. Green, the

union delegate from London.

They all spoke at length about the rights of

the workers, and their determination to fight the

employers to the bitter end. The employers were

criticised for their tyranny, and Perry was castigated

for his treatment of the hired hands who were forced to

return to Wolverhampton. |

| After the meeting, Perry appealed to the mayor for

police protection for his employees, stating that they

were threatened with violence by the strikers.

On Thursday 24th October, the mayor, George Robinson, and four

magistrates, Whitgrave, Fryer, Walker, and Andrews held

a meeting at the Town Hall with Edward Perry and the

London trade delegate, Mr. Green, in an attempt to

resolve the situation. Both sides were deeply

entrenched, and so the attempt failed. |

The Theatre Royal in Cleveland

Road. |

|

Edward Perry Fights Back

The strike continued for month

after month, and Edward Perry collected evidence in

support of a charge of conspiracy against the strike

leaders. The members of the strike committee, Duffield,

Gaunt, Piatt, Rowland, and Woodnorth were indicted for

conspiracy, as were the London delegates.

The trial took place at Stafford

Assizes in August 1851 with Mr. Justice Erle presiding.

Perry called many of his workmen as witnesses, and the

union produced a copy of their rates book, stating that

Perry’s wages were considerably less than those paid by

other employers. Perry said that this was because he had

gone to great expense to automate the manufacturing

process. He showed the court two colanders, one made the

old fashioned way, by hand, and another made in one

piece by machine. The hand-made colander consisted of

seven pieces of tin which were raised, punched, and

jointed together by the tinmen, who were paid twelve

shillings a dozen for the job. The other colander was

completely produced by machine, except for the fitting

of the handle. For this the tinmen were paid one

shilling a dozen, but because of the speed of the

process, and the large numbers produced, the tinmen

actually earned more money.

The jury were greatly impressed

with Perry’s argument, and found the defendants guilty

of conspiracy. The counsel for the defendants

immediately appealed against the verdict on technical

grounds, and so the defendants were bailed until the

case could be heard in London before the judges.

Back in Wolverhampton the

defendants summoned Edward Perry before the local

magistrates on a charge of perjury for remarks he made

during the trial. After hearing statements from both

sides the Wolverhampton magistrates dismissed the

charge.

The

final outcome

The appeal was heard on 26th

November, 1851 by Lord Campbell, and justices Patteson,

Coleridge, and Erle. The appeal was rejected, and a

sentence of 3 months imprisonment with hard labour was

imposed on the London delegates; W. Peel, T. Winter, and

F. Green, and also on 4 members of the strike committee;

Rowland, Gaunt, Duffield, and Woodnorth. The 5th member

of the committee C. Piatt was let off with one month’s

imprisonment. Each of them had to pay a fine of 1

shilling and costs, which were very high. They were sent

to Stafford Gaol to serve their sentence.

As a result of the high costs

involved, the National Trade Association was declared

bankrupt. The men were now penniless, and liable to a

long term of imprisonment because of their inability to

pay the heavy costs. Unsuccessful attempts were made to

raise the money by subscription, and so they appealed to

Edward Perry, who generously paid the remainder of the

costs, so allowing them to leave prison.

The strike ended after 18 months,

and the unions decided to leave the employers alone,

which they did for nearly 30 years.

Edward Perry was twice elected

Mayor of Wolverhampton, first in 1855, and again in

1856. He married Sophia, but had no children. In

1856 he was one of the founders of the Wolverhampton

Chamber of Commerce, and its president from 1856 until

1864. Just before his death in 1871 he built a large

house at Tettenhall called ‘Dane’s Court’ but sadly

didn’t live long enough to settle in. When the house had

been completed, he was taken ill and soon died.

By the 1880s, the japanning and

tin-plate industries were in decline, mainly due to

changes in fashion, and the development of

electroplating. The over-decorated and fussy designs

greatly appealed to the Victorians, but not to later

generations. The last vestiges of the industry had more

or less disappeared by the 1920s.

References:

| W. H. Jones, |

"Japan, tin-plate working, and bicycle

and galvanising trades in Wolverhampton",

Alexander and Shepheard Limited, London,

1900. |

| John Jones, |

"The Mayors of Wolverhampton" vol.1,

Whitehead Brothers, Wolverhampton, 1880. |

| Frank Mason, |

"The book of Wolverhampton", Barracuda

Books Limited, Buckingham, 1979. |

|

|

|

|

Return to

unrest and the strike |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|