|

Racing Tragedy and Success

Dario Resta had driven for Sunbeam for several years. He

was originally recruited in 1912, and when racing was banned in Europe at the

outbreak of war, he continued to race for Sunbeam in America. After a little

while he moved with his family to Bakersfield, California and created a small

racetrack at Buttonwillow. In 1923 he returned to Europe as a Sunbeam team

member for the Spanish Grand Prix at the Autodrome Nacional, Sitges. The race

took place on October 28th, but unfortunately Resta had to retire after 150

laps.

1924 was a bitter-sweet year for

Sunbeam’s Experimental Department, many racing successes were achieved during

the first half of the year, but tragedy soon followed. On March 29th, Resta came

2nd in the Kop Hill Climb, and on April 21st he finished in 3rd place in the

37th 100 mph. Long Handicap at Brooklands. On May 17th, driving one of the 1924

Grand Prix cars, he won the Aston Clinton Hill Climb, and also in the same car,

finished in first place in the South Harting Hill Climb, on May 31st. His last international race

took place on August 4th when he finished in 9th place in the Grand Prix de L'Europe, at Lyon, France.

|

|

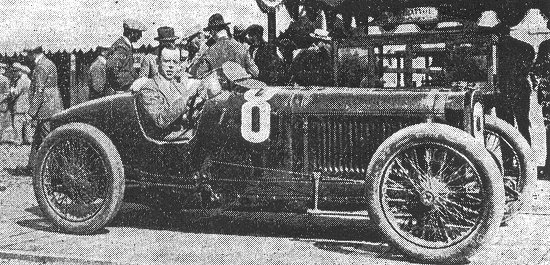

Kenelm Lee Guinness at the

wheel, with mechanic Bill Perkins.

Courtesy of Jan Jeavons. |

| His last race was at the

International Class ‘E’ Records meeting at

Brooklands on September 3rd. Dario Resta competed for

Sunbeam along with mechanic Bill Perkins in their 6

cylinder G.P. car. Things went well until a tyre

came off a wheel rim on the 4th

lap. Resta lost control of the car, whilst was

travelling at around 115 mph. The car collided with

a corrugated iron fence, and Resta was instantly

killed. Bill Perkins ended-up in hospital, due to

his injuries. At the inquest it was mentioned that a

rear tyre had been punctured by a security bolt that

had been broken after hitting a bump in the track. |

|

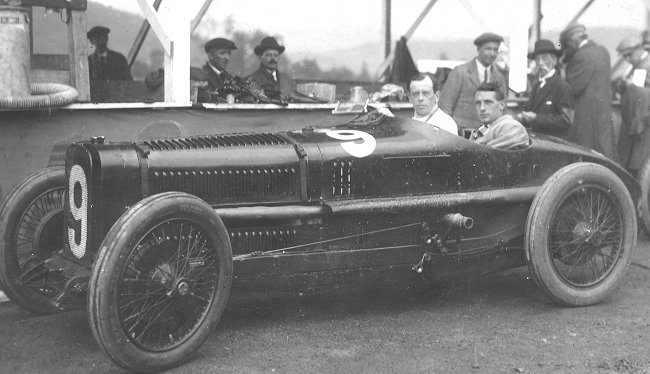

Kenelm Lee Guinness in his

car at the Grand Prix de L'Europe at Lyon, France. |

|

The specification for the

1924 two-litre Sunbeam cars. |

| Sunbeam’s next major event

was the Spanish Grand Prix at Lasarte, San Sebastian,

on September 27th. Two of the company’s

drivers, Henry Segrave and Kenelm Lee Guinness took

part in the race along with their mechanics.

Guinness’s mechanic should have been Bill Perkins,

but he was still in hospital recovering from his

injuries received at Brooklands, three weeks

earlier. He was replaced by Tom Barrett. |

|

Kenelm Lee Guinness and Tom Barrett

before the race. Courtesy of Jan

Jeavons. |

|

All went well for Guinness and Barrett

until the 11th lap, when

Guinness lost control of the car on the slippery

road surface after hitting a rut in the road. The

car turned through 180 degrees, and rolled over.

Guinness was thrown clear, across a steep railway cutting,

and collided with telegraph wires. He suffered serious head

and limb injuries, and never raced again. Unfortunately Tom

Barrett was trapped in the car, where he died from the

terrible injuries he received during the crash.

Due to this accident, the rules regarding

mechanics riding in cars were changed, and soon would be a thing of the past. Segrave on the other hand had an excellent race and finished in first place at

an average speed of 63.5m.p.h. No doubt he would have retired from the race had

he realised that Barrett was dead.

Guinness never fully recovered. After the race he became

increasingly mentally unstable, suffering from bouts of depression, and

delusions. He often imagined that he was continuously being followed. His

marriage was dissolved in 1936, and he was admitted to a nursing home. In April

1937 he returned to his home, 'Melbury', Kingston Hill, Kingston upon Thames,

and was found there on April 10th after committing suicide. He had gassed

himself. At the inquest the coroner recorded that the cause of death was asphyxia and carbon

monoxide poisoning from coal gas. He was buried at Putney

Vale Cemetery on 14th April, 1937.

|

|

|

Read about

Tom Barrett |

Henry Segrave described the race in his book "The Lure of

Speed" published in 1928. This is his description:

On the night after the zoo-mile race Guinness and I went

off to San Sebastian, where we were to drive a couple of supercharged

2-litre Sunbeams. The course consisted of 35 laps, totalling 387½ miles, of

a circuit which looked at first all right to the eye, but turned out to be

in an abominably dangerous condition. The corners were supposed to be sanded

so as to give the tyres a reasonably good grip. But the Spanish workmen,

true to their tradition of avoiding any unnecessary work, discovered that it

was very much easier to dig clay out of a neighbouring field and sprinkle it

on the road rather than go some little distance off and get the sand which

they should have used.

This nearly cost Guinness his life, and

led to a crash in which his mechanic, Barrett, was instantly killed.

Just before the race I said to Bill

that I proposed to hang back for a few laps and see what was going to

happen. There were fourteen starters, representing Germany, Italy, and

England, and it appeared to me that on this occasion it would be good policy

not to go out too hard at first, especially as I had no great experience of

this very twisty circuit. Bill, however, said he proposed to go all out from

the drop of the flag. As a matter of fact, as I have noticed in many

previous events, Guinness's first lap is usually the fastest. Provided his

car runs consistently the later laps will not be much slower than the

initial one, but there are just a few seconds difference.

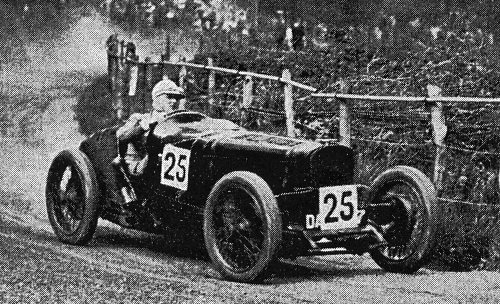

Henry Segrave at the wheel of one of the 2 litre cars

at Shelsley Walsh in May 1925.

He was taking one of those treacherous

turns on a road surface covered with wet clay, when his car refused to

answer its steering, left the road, ran up a steep incline on the left-hand

side of the road, then turned over three times down into the road again, and

finished up against a stone wall on the right-hand side.

Along the right side of the road were

telegraph poles and a railway cutting running parallel with it. Guinness and

his mechanic were both flung clear of the car the last time it turned over,

and actually went over the telegraph wires, and fell in the railway cutting.

Barrett, the unfortunate mechanic, was

instantly killed, while Guinness suffered severe injuries to his head and

legs. I shall never forget my amazement and dismay when I arrived at the

scene of the crash a few minutes later; and then for four consecutive laps I

had to pass the two stretchers carrying them to the field dressing-station,

not knowing whether my friend was alive or dead.

One's reaction in a case like this is

peculiar, because, knowing Bill as I did, I knew perfectly well that he had

not turned over through an error of judgment in driving, and therefore

something must have broken in his car to cause the accident. As both our

cars were identical, it followed that what happened to his car must happen

to mine, and so, not knowing what had caused Bill to turn over, I drove the

rest of the race waiting for anything to happen. It made me handle that car

as though it was made of glass!

In 1926 Louis Coatalen moved to the STD factory at Suresnes near Paris.

Although he spent most of his time in France, he continued to work part time

at Wolverhampton.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Sunbeam,

Talbot, Darracq |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed to

Land Speed Record |

|