|

In 1865 we have, thanks to J. C. Tildesley, a slice in

time picture of the local industry.

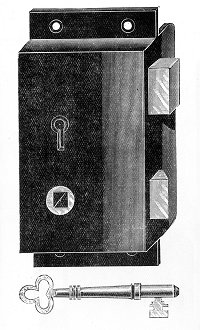

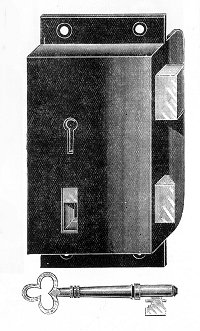

Tildesely’s main classification of the lock trade is into

the trade of Wolverhampton and that of Willenhall. Clearly they are both

important trades in their own areas but he does not suggest that the

scale of manufacturer is noticeably greater in one town than in the

other. But he does see some clear distinctions between them. The first

is that in Wolverhampton the locks are based on tumblers and levers and

in Willenhall and elsewhere they are based on wards. Secondly the locks

produced in Willenhall are "of inferior quality". Thirdly the lock trade

in Willenhall is divided amongst "many masters, the majority of whom

employ only some six or eight men or boys". This has resulted in

considerable competition, exploited by purchasers to drive prices down,

so that "excellence of workmanship has given way to rapidity of

production". The implication is that Wolverhampton’s lock industry is

based on much larger firms, though the only one which gets a mention is

Messrs. Chubb and Son.

Brewood, Coven and Pendeford also get mention as making

the ironwork for fine plate locks, which are completed in Wolverhampton.

Short Heath and New Invention make cabinet locks "but the articles

produced are much inferior to Wolverhampton make". The lock trade in

Walsall "has much extended in recent years" and Wednesfield is noted as

making some locks as well as keys, but in both places "the lock trade is

only a supplementary brand of industry".

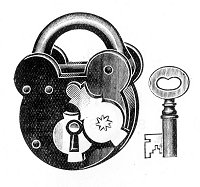

At this time, Tildesely records, the principal overseas

markets are Australia and New Zealand. India is a large market for

padlocks. And the Continent provides a market for brass and ornamental

padlocks. The United States used to provide a considerable market, more

than half the locks made in the district being sent there. But now their

home industry was expanding and trade to the US was declining. But "the

development of new empires, and the opening up of fresh fields of

commerce in our colonies, augur well for this department of local

industry".

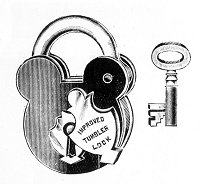

There was foreign competition, mainly from America, France

and Germany. The Americans use very fine casting sand which does away

with the need for any filing of the castings, which enables locks to be

made ten times faster. But their locks "are unenduring and insecure" and

are little threat outside the USA. Continental locks are no better.

Although they are elaborately decorated, they lack "the strength and

practical usefulness" of English locks.

Even though Tildesley thinks it will take some time

"before the French consumers will abandon their own flimsy decorative

articles in favour of plain practical English locks" the example of

these fancy foreigners does give Tildesley some cause for concern:

"neither …have locks and keys made in this district kept pace with the

demand for decorative art workmanship, which is the natural result of

the refining influence of an increasing civilisation, and the spread of

education amongst the people". And "it cannot be denied … that Mr.

Ruskin’s theory, on the union of art and handicraft, might he studied

with advantage by the locksmiths of this district, to whose productions

might be given increased symmetry and beauty, without in any way

destroying their more practical qualities."

He also says that "perhaps no extensive branch of local

industry has taken less advantage of the recent progress of mechanical

science than the lock trade. In most cases, they are constructed now in

precisely the same manner as they were twenty years ago. To the fact of

the trade being so much in the hands of small capitalists, must be

mainly attributed the lack of that enterprise and progression which have

characterised other departments of local industry".

The lives of those working in the industry also has his

attention, where he finds that things have "much improved of late years,

but there is still room for amendment". Working hours were from 6 a.m.

to 7 p.m. in winter and from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. in summer "but in too many

instances those hours are exceeded". Only 10% of the workforce is women

but the widespread employment of boys under the workhouse apprenticeship

system causes concern, though there is less of it than there used to be

and the boys are better treated.

Generally the blacksmiths work much better than they used

to, even though they still drink the health of St. Monday – that is,

they do not work on Monday, turning Sunday and Monday into a week end

break. But they have taken advantage of the facilities for

self-improvement offered to them and "in one lock factory, which may be

taken as a fair example of the others in the district, 70 per cent. of

the artisans are members of Friendly Societies, 50 per cent. can read

and write, 15 per pent. are members of a Mechanics’ Institute, 10 per

cent. have accounts with the Post Office Savings Bank, and 5 per cent.

are the owners of the freehold cottages in which they reside."

Tildesely, who is not averse to including local folklore

in his account, does not mention one still-remembered feature of

Willenhall lock workers. They were said to spend so much of their lives

hunched over a bench that they developed a permanent distortion of the

spine. So many men were so afflicted that Willenhall was known as

"Humpshire" and, it is even said that the pub benches had hollows in

their backs to accommodate the humps. But no evidence of this curious

furniture has ever been found.

Many years later, another Tildesley, Norman W. Tildesley,

adds a few details (in his History of Willenhall, Willenhall UDC, 1951,

published "to commemorate the Festival of Britain") adds a few details,

apparently from the same period. "The locksmiths were assisted by their

wives and members of their families, together with one or two

apprentices. Children in those days were set to work at the tender age

of nine or ten years. They were first taught how to file and humped

backs and twisted shoulders were the result of this early training. A

considerable number of these children were placed as apprentices by the

parochial officers. The lot of the parish apprentices was indeed a

grievous one. Many of these lads came from the Tamworth Workhouse and at

ten and eleven were apprenticed to the lockmakers to spend the next ten

years as members of their households. Many of the masters were harsh and

unscrupulous and looked upon these unfortunate children as a form of

cheap labour which they could exploit to the full. The small cramped

workshops, hard work, long hours and poor food wrought havoc with their

frail bodies and the death rate amongst them was high, many of them

perishing from consumption and other kindred complaints". Bad though

this may be, it is worth remembering that the locksmith’s own children

may have fared no better and the apprentices became part of a whole

household that was barely scraping a living.

|