page 3

Demonstrations of resistance to fire

Thomas Milner had observed that the asbestos, mica or alum he used to

insulate his ammunition boxes gave off steam when the boxes were heated.

He reasoned that if asbestos, mica or alum were used as cavity

insulation in safes, and holes punched in the inner walls, then when the

safes were affected by fire, steam would escape into the interior and

protect the contents from destruction. He patented this invention in

1840, and the hugely prosperous Victorians fell over themselves to buy

this protection. When the patent lapsed in 1854, Price and most safe

manufacturers in the country were more than ready to make use of the

idea. Milners had been demonstrating their safes' capacity to preserve

money and documents by placing the safes inside huge public bonfires and

then dowsing the fire and removing the magically surviving contents to

the astonished applause of the onlookers.

Price set up his first demonstration of a safe using Milner's principle

in June 1854. One of Milner's foremen assisted. But it was not a

success. He recorded this disappointment

in his Treatise:

"Soon after taking over the business of which I am now proprietor,

relying on the statements of other makers as well as on the assurances

of a person in my employ, as to the fire-resisting capabilities of safes

made fire-proof by the use of a simple non-conductor (which activated

the production of steam to preserve the contents) I had a public test of

two safes made on this principle and invited my friends and fellow

townsmen to be present a the trial.

One safe was in an intense fire for three hours, and the other for

five hours - Mr. Milner's foreman and his agent and lock manufacturer in

Wolverhampton were present and assisting me. The contents comprised

books, bound in leather, loose papers and a parchment deed. After the

safes were cooled and opened, the books were found to be burnt black at

the edge for some distance towards the centre of the paper; the loose

papers were more or less burned, the leather destroyed, and not a

vestige of parchment could be found. The disappointment, vexation and

chagrin I experienced at the result of this my first test, caused me to

study the manufacture, not only as a mechanical art, but as a science

requiring some research. From that day, it has had my undivided study

and attention."

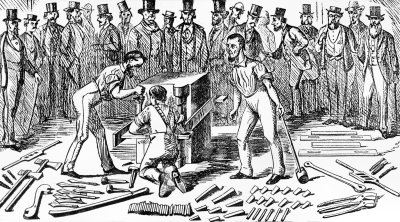

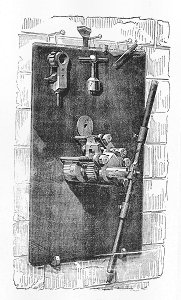

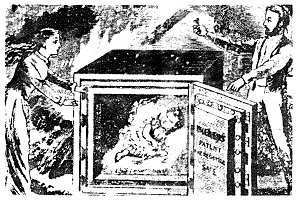

| An old woodcut showing a

public demonstration of the security of a safe. In this case a

group of German operatives were failing to effect an entry despite

all their equipment |

It was this public humiliation which motivated him to write his huge book. Milners

had always claimed in their advertisements that their own safes would

protect "deeds" from fire. But they must have excluded parchment deeds

from their public tests. "It would invariably be assumed (by the public)

that 'deeds' meant parchment deeds, even though the word parchment was

excluded." Price should have remembered that Bilston's

bonnet makers used to buy offcuts of parchment from his father's print

shop. Parchment is made from animal skin and the bonnet makers used to

boil it for size to stiffen bonnet brims. Steam could never be used to

protect parchment from heat. It was melted, cooked, frazzled by steam.

Paper, made from cotton waste and wood pulp, survived, as did money and

precious metals. What incensed Price was that Milner's foreman had

allowed - perhaps encouraged - the novice safe maker, himself, to

include parchment in his first challenge, knowing it would frazzle.

He

consulted experts and came up with a design for a special compartment

within a safe for the storage of parchment documents which was proof

against steam. He patented this, and challenged Thomas Milner’s son,

William, who had inherited his father’s manufactory, to publicly admit

the shortcomings of his Phoenix safe and acknowledge that only a

Price safe could properly protect parchment.

From there on Price was on his high horse, the bit between his

teeth, hell bent on outdoing all competitors, and above all, William

Milner, son of Thomas, the founder of the company.

But Price was not above sharp practice himself. Far from it! The

locks on Price's safes in the early days were made by Charles Aubin,

whose lock trophy had been purchased by Mr. Hobbs. Aubin had also worked

for Samuel Chatwood, another powerful competitor in the safe industry.

Later Price patented Aubin's design as his own. Then there was the bad

feeling caused by recruiting William Dawes, again from Samuel Chatwood.

It was dog eat dog.

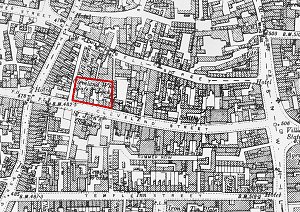

|

The 1903 Ordnance Survey

Map shows the Cleveland Works (here outlined in red) on the

north side of Cleveland Street and the east of Bell Street.

This area was still predominantly industrial at the time. |

All this time, George Price was working on converting Noakes' old

workshop to a steam-powered manufactory. The following item appeared in

the Wolverhampton Chronicle for June 20th 1855:

We have inspected the new works of Mr. Price and were as much

surprised as pleased with out visit .… The manufacture of wrought iron

safes we have always considered one of the legitimate trades of

Wolverhampton as it is well known that both the iron plates of which

they are made and the locks which secure them, are made in the

neighbourhood of the town. And yet, their manufacture has been almost

entirely confined to London and Liverpool .… We were very much pleased

with the machinery and fittings and also with the steam engine made by

Thompson and Co. of Bilston. The buildings are substantial, the rooms

wide, lofty and well ventilated. Crowding of workmen is completely

avoided. The iron of which the safes are constructed goes in at one end

of the building in sheets and comes out at the other end a finished and

painted safe, ready to be lowered into the carrier's wagon.

Conflict with Thomas Milner and Son

We have to remember that William Milner, his company well established

in the trade, could afford to ignore this newcomer. It was his father,

Thomas, who was the inventor. William had his own fish to fry, and might

have been astonished that his refusal to respond personally to Price's

challenges had such a profound effect. Price, self taught, fervently

committed to the principles of Freemasonry, and desperate for his

invention to be noticed, went on a lecture tour of mechanics' institutes

and philosophical societies in Glasgow, Belfast, Cardiff and Dublin.

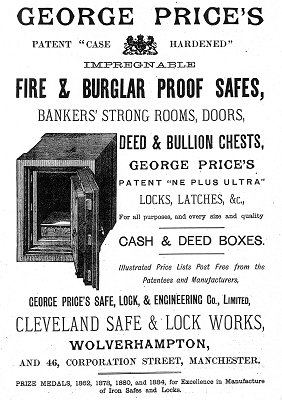

|

He preached against the persuasive, exaggerating claims

of advertising - particularly in the case of Milner - and

waxed eloquent on the need for precision in disclosing the

specifications of safes. He was scathing about the

shortcomings of Milner's products. Still no response from

William Milner, but there was a lot of public concern about

the gangs of burglars who were roaming the country on the

new fangled railways and raiding the counting houses of the

huge new mills and factories springing up in the north.

This was the point where Price decided to publish his

observations on the security trade and be damned. His

Treatise was published in 1856, only two years after he

began to produce his (truly) fire resistant safes. He was a

man obsessed. The footnotes of the section on fire

resistance contain quite libellous criticisms of Milner's

specifications. But William Milner still could not be

provoked into trying to protect his father's reputation.

|

However, Milner's agents began their own campaign of

besmirching Price's name, and the battle for customers

continued around new issues: how resistant or otherwise were

safes to burglarious drills? Could gunpowder be inserted

into keyholes, allowing safes to be blown up?

A low point was reached at Burnley in 1860 when Daniel

Ratcliff, the new Liverpool agent - who later became William

Milner's son-in-law - finally took on a direct challenge

from Price to prove Milner locks were gunpowder proof. All

the northern newspapers were present and Price's safe was

shown to be far superior to Milner's, which caved in to a

charge of gunpowder. Price was declared 'Champion safe

maker'. But in a fit of anger, Ratcliff found an out-

of-date Price safe, whose lock was not gunpowder proof,

stuffed it with gunpowder and ignited it. The safe exploded

and a child was killed with a shard of metal.

No-one was prosecuted, but the Coroner censured Price, along

with Ratcliff, for 'attempting such a dangerous experiment

in the presence of the public'.

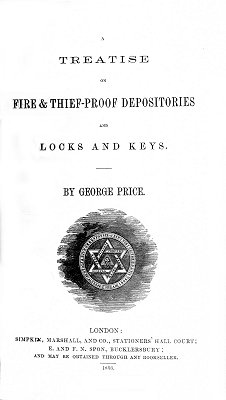

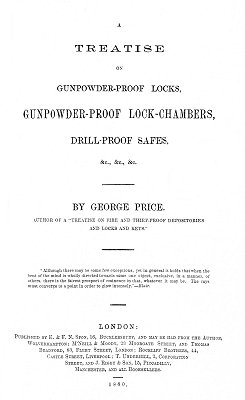

|

The title page to the Treatise. The

drawing on it is full of Masonic

symbolism. |

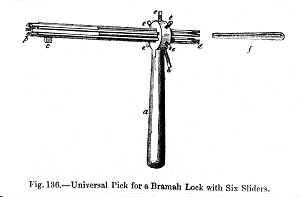

An illustration from the Treatise,

showing a device for picking Bramah locks. |

This injustice mortified Price. He had always been

fanatically safety conscience, and felt that this moral

condemnation in a courtroom meant he was unfit to

continue to be a Freemason. He had a mental breakdown,

and later, in 1863, he persuaded Spon to publish a four-

hundred- and- twenty- line 'poem' - a Thesaurus of world

religions, in which he asked the same kinds of questions

he had always asked about locks, keys and safes. Which

is the best? |

Of this Great Church, which is the purest branch?

Of forms of worship so very numerous,

There must be some that near perfection be,

Though in all earthly institutions, Imperfections will be

found.…

There are Trinitarians and Arians,

Unitarians, Socinians, Arminians,

Antinomians, Calvinists, Brownists,

Presbyterians - English and Irish.

Wesleyan Methodists - Old and New;

Independents, Mystics, Quakers, Shakers,

Universalists, and Destructionists.

Sabbatarians and Moravians;

Swedenborgians and Moravians;

Baxterians and Hutchinsonians;

Lutherans and the Millenarians...Oh, where is Christ's

Church on earth to be found? |

Having withdrawn from Freemasonry, he finally converted to the Catholic

Church. Before publishing 'The Church of Christ', Price had published in

1860'A Treatise on Gunpowder-Proof Locks, Gunpowder-Proof Lock-Chambers,

Drill Proof Safes &c &c &c.' In this book he listed in detail how the

child had been killed in Burnley.

|

Image opposite: In his second

treatise Price is careful to describe this as "Milner's

Phoenix Escutcheon, engraved from the one on the safe blown up in

Burnley".

|

|

|

The Masonic symbolism from the first treatise is missing but there

is a quotation from Robert Blair: "Although there may be some few

exceptions, yet in general it holds that when the bent of the mind

is wholly directed to some one object, exclusive, in a manner, of

others, there is the fairest prospect of eminence in that, whatever

it may be. The rays must converge to a point in order to glow

intensely". This claim to superiority of knowledge may be a suggestion that he

knew more about this matter than anyone else - including Milner. |

| In January 1863 a gang using skeleton keys entered the

warehouse of a woollen mill in Batley, Yorkshire. They tried breaking

into the mill safe, which contained a large amount of gold. They

partially succeeded but then lost patience with their implement,

described as "the largest burglar machine ever constructed", and began

bashing the safe with a crowbar.

They left their machine behind when the millowner disturbed

them. It was so massive that seven men had been needed to carry

it in pieces, to be attached to the safe at the scene of the

burglary.

Delighted with this find, the Dewsbury Constabulary put the

machine together and displayed it in the police station. As soon

as his agent told him of this, George Price contacted a Dewsbury

company, who had one of his safes, and arranged for it to be

tested in public with this great implement.

It survived the test without even a dent and Price's order

book swelled again.

|

A drawing, from the second treatise, showing

"The burglars' drilling, boring and cutting machine".

|

A baby, safe and sound, after a fire.

Presumably a fanciful notion - the baby would have suffocated and been

steamed. |

He eventually published in 1866 a short, vindictive book

entitled "Forty Burglaries of the years 1863-45", recording the regular

cracking of Milner safes. But, he boasted, when burglars drilled a hole

in the roof of a provision dealer in Kirkgate, Leeds, and saw a George

Price safe, they left without bothering to touch it.

He recorded with

glee a spectacular jewellery robbery from a shop in Cornhill, London -

from a Milner safe, of course.

The safe was advertised as "Holdfast" and

"Thiefproof" and the shop owner, Mr. Walker, sued Milners, his case

being that it was neither. |

A well-known cracksman, who Price refers to as

"Convict Caseley", gave evidence that he could open a similar safe in

half an hour. "He is a man of keen wit, coarse in quality and

inexhaustible in quantity, that bubbled up like bad petroleum". He

showed "the instinct of an actor for effect; the craving of an orator

for applause; the delight of an artist in flattery." Caseley described

himself as "one of the dangerous classes who society had found out and

locked up". The cleverest men at the bar, says Price, were those most

struck with the cleverness of the uneducated Caseley. Indeed, it was a

pity he could not be employed in Scotland Yard - a thief set to catch

thieves. But Mr. Walker lost his case, with the judge ruling that he

should have employed a watchman to watch his shop. Presumably Convict

Caseley's claim was not accepted, and the judge commented that it took

twenty four hours for the thieves to break into the safe, proving it was

"strong enough". The press took up the judge's comments to condemn

companies who did not employ watchmen to watch the safes and called for

an increase in the pay of policemen.

|

|

|

Return to

page 2 |

Return to the

list of makers |

Proceed to

page 4 |

|