Christopher Dresser is now one of

the most fashionable names in design history - and in antique

dealing. Dresser’s main occupation as a designer – of almost anything

and everything – and his business mainly involved selling his designs to

manufacturers. The matter of interest to this web site, concerned

as it is with the history of Wolverhampton, is what did Dresser do in

Wolverhampton and for its companies. Wolverhampton was one of the

greatest centres for the production of hollowwares and other domestic

items. And little is known about who actually designed most of

Wolverhampton’s products. It seems as if most of it was done in

house but it is hard to be more specific than that. But it is

clear that there was, in Wolverhampton, a greater interest in design

than there was in many other manufacturing centres. Wolverhampton,

under the influence of George Wallis, showed a consistent interest in

matters of good design. Wolverhampton makers were consistent exhibitors

at international exhibitions and Wolverhampton organised more than its

fair share of industrial exhibitions, both before and after the Great

Exhibition of 1851. As late as the exhibition of 1902 it was Orme, of

Orme Evans, a leading light in the organisation of the exhibition, who

was still busily explaining that one of the aims of such exhibitions was

the improvement of standards of design. And Wolverhampton had its

own art school from 1851. It may not have been large but it was

there and it was teaching students with the intention that they should

be industrial designers.

1. The problems

of finding Dresser

If we are to look for Dresser in

Wolverhampton we immediately run up against the standard problem in

researching Dresser: there is very little written evidence,

especially from Dresser himself. What documentation there is tends

to come from the archives of the companies he worked for or to be

secondary. This material does give us excellent evidence of some

of Dresser’s designs. More evidence comes from finding pieces

which are marked with Dresser’s name and, fortunately, Dresser seems to

have been keen to have manufacturers put his name on pieces he had

designed (a commercially useful thing for both parties and maybe also a

reference to Dresser’s interest in Japanese productions). Of

course, Victorian businessmen were not quite as fussy as we might be

about the authenticity of their claims and it is possible that pieces

which proclaim themselves to have been designed by Dresser were not.

After that we are left with

trying to identify pieces as being by Dresser on “stylistic grounds”.

That means saying that a piece looks as if it was designed by Dresser.

In assessing whether a Wolverhampton made object was designed by

Dresser, or was simply influenced by Dresser, or had nothing at all to

do with Dresser, there is a number of matters to be taken into account.

Most of these are fairly obvious and well known (and carefully taken

into account by the authors of most published accounts of Dresser’s

work) but some of them at least are worth setting out here, not least

because there is little documentary evidence of Dresser in Wolverhampton

and attribution on stylistic grounds is very often going to be all we

have to go on in trying to establish which firms, if any, he worked for.

a) First, the most obvious

difficulty: if an object looks like a Dresser design, does that mean it

was designed by Dresser? Much of the argument about what Dresser

designed or did not design revolves around this problem, which is one

well known to archaeologists as well as others. If vase A is by Dresser

and vase B looks very much like it, it is tempting to say that vase B is

by Dresser. Then vase C is found and looks very much like vase B and the

temptation is to say that therefore vase C must be by Dresser. Then vase

D comes along and has features in common with vase C. So vase D is a

great risk of being identified as being by Dresser too and that may

happen even though vase D is nothing much like vase A at all.

This problem is made more severe

if anyone trying to identify a Dresser article on stylistic grounds

seizes upon single features. As Angeline Johnson has pointed out to me,

it is easy to identify the spout on a water can or the handle of a ewer

as being like those on known Dresser jugs. But that does not make a

Dresser design. You have to look at the whole object and all its

features to get near the truth.

b) Nearly all of these

pieces have peculiarities which are now identified as indicators of

Dresser. What we do not seem to know is whether or not Dresser designed

items which do not have these now well known indicators. It is notable

that in his book on interior design he refers to his characteristic

style as the "new style", separating it out from designs which we might

refer to as being in the mainstream tradition. This, as well as his

other writings, suggest that Dresser designed in the mainstream too.

Further, if we consider the size of his studio operation and its

apparent success, it seems highly likely that the known designs would

not have fully occupied or fully financed it. He must have

designed very many things which nowadays we would not identify as

Dresserish. If this body of work does in fact exist then we

do not know the full range of his work. This matters when establishing

what work Dresser did in Wolverhampton, simply as a matter of accuracy

and record – Dresser might have designed lots of things made in

Wolverhampton but without any of the style peculiarities (and very

peculiar some of them are) which is all we often have to identify his

pieces. It also matters in establishing what one is actually doing when

attributing items to Dresser on design grounds.

c) This problem is

related to, but not covered by, the problem that Dresser’s design

principles could have lead others to produce designs similar to his.

Take, for example, his emphasis on working with materials, not against

them; and on producing functional objects; and on the need to understand

production methods. All of these, like much else in his design theory,

comes directly from the South Kensington School and could be described

as a commonplace of Victorian industrial art. Certainly they are points

which were constantly re-iterated by George Wallis. It seems to me that

if a manufacturer decided to produce a water can for domestic use, and

designed it in accordance with these principles, he is likely to have

come up with much the same result as Dresser would have done. Similar

materials and similar production methods, applied to similar articles,

produce similar designs. As an example we may take what we might call

Dresser’s straight sided vessels. It has to be remembered that, part

from a cylinder, the easiest shape to make from sheet metal is a cone.

The cut out sheet only needs bending, not hammering or pressing or

stamping into shape. That is why so many metalware water ewers are

conical – or, to be precise, the bodies of them are, since the top of

the cone has been removed, frustra of right cones. Many of the

vessels which are said to be characteristic of Dresser are simply one or

more frustra connected to each other. Such a design is quick and simple

and follows from manufacturing cheaply.

d) We might

say that the next problem is that of Dresser’s influence. If we

have an object which looks as if it might have been designed by Dresser

then, before saying it is by Dresser, we have to bear in mind that

Dresser wanted other people to design objects in his style. He saw

himself not just as a designer but as a teacher of design. He points out

that, wherever he went, he tried to write articles in local newspapers

and to give talks to local groups. This was not just pr work. And it was

in addition to his books and the articles he produced in national

magazines. He was a publicist for good design. It seems to me

that if a place like Wolverhampton was not producing articles in his

style, Dresser would have been disappointed.

What that indicates for

Wolverhampton designs it is hard to say. The factors are that Dresser

was certainly known in Wolverhampton; his practice and his cause may

even have been promoted by George Wallis. Dresser’s work for Perry may

have acted as good pr and encouraged other Wolverhampton firms to

commission him.

But on the other hand we have to

allow for the fact that most firms in Wolverhampton knew exactly what

the other firms were producing. Wulfrunian manufacturers were probably

not immune from the common Victorian practice of freely copying other

people’s successful idea. The introduction to a catalogue, from

about 1890, issued by Orme Evans says: "We are prepared to supply

almost every article in sheet iron, steel, brass, copper or enamel, and

our close touch with the trade throughout the United Kingdom enables us

to be constantly bringing our articles thoroughly 'up to date' and

exactly suited to British tastes and requirements". The least that

shows is a willingness to be, shall we say, heavily influenced by other

people's designs. The commercial travellers would report on what

was on the market and what was selling and the company would react

accordingly.

e) Nor is there any reason

to suppose that Wolverhampton makers were incapable of producing their

own designs, quite uninfluenced by Dresser. Because of the context in

which they were working their designs might tend towards looking

Dresserish. And they could read Dresser’s books and articles as

well as anyone else. They were open to influence by Dresser and there is

no reason to assume that any article they produced which looks

Dresserish was not designed by them.

2. Dresser’s

connections with Wolverhampton

Bearing in mind all those

caveats, and noting that how firmly one attributes anything to Dresser

depends on the evidence and, especially, the weight one attaches to the

evidence, we can now start the search for Dresser in Wolverhampton.

It is best to start with the case which is established beyond reasonable

doubt and then to proceed to other suggestions.

Richard Perry Son and Co

The strongest evidence that

Dresser had anything at all to do with Wolverhampton is the work he did

for Richard Perry Son and Co.. That Dresser did design for this company

is established beyond a peradventure, both by the evidence of Pevsner’s

original article on Dresser and by signed pieces. If all the pieces

illustrated in Andrew Everett’s works were indeed designed by Dresser

himself, then the amount of work he did for that company was

considerable.

|

Water can by Perry. The

square shape is unusual for these items. The hoop

handle, sometimes quoted as a Dresser characteristic, is a

commonplace and was used on watering cans at least as far

back as the early 19th century. There are no raised

lines round the body to strengthen it.

Photo by courtesy of Ken

Cummings. |

| Chamberstick by Perry. A

Dresser design. The shape of the handle makes for an

unbalanced design but at least it is practical. Most

of Dresser's other designs for Perry's chambersticks are

quite impractical and would result in burnt fingers at the

least. |

|

|

'Kordofan'

chamber-stick, which was made by Perry in conjunction

with Christopher Dresser.

It was produced in brass, or tinplate, and

enamelled in the fashionable colours of the period. This

example, unusually, is in the original finish.

He also has another example, with no Dresser label,

that was produced by Griffith and Browett Limited, of

Birmingham. |

| A close-up view of the maker's mark. |

|

A George Wallis connection

But there are other, more

tenuous links, as well. There are many indications of close links

between Dresser and George Wallis.. The relevance of this is that Wallis

was a Wolverhampton man by origin and, although he lived and worked in

many other places, spending most of his working life in London, he

remained a Wulfrunian, visiting the place often. His children saw him as

a Wulfrunian: they erected a memorial to him in St. Peter’s church in

Wolverhampton and arranged a memorial exhibition to him in the

Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Dresser a pupil at the South Kensington

School when Wallis was a teacher there and seems to have thought that

Wallis was one of the best of them because his practical experience of

machine work informed his views of design and his teaching and practice

of design. The apparent regard of one man for the other may also have

had some base in both of them being the only members of the set who did

not have a university education – something that Dresser’s later

enthusiasm for his doctorate seems to emphasise.

There are later indications that

the two men maintained contact. When Wallis was presenting to the

Royal Society the results of his attempts to develop a cheap and

effective reprographic system for the better distribution of images, he

specifically mentions that Dr. Dresser was working on a similar project.

The fact that he knew about it and no one did, suggests a continuing

connection.

One of Wallis’s main interests

in Wolverhampton was the Art School and a leading supporter of the Art

School was Henry Loveridge. There seems to be a possible link between

Wallis, Loveridge and Dresser, a link which would have been based on a

mutual interest in design.

Chubbs

Much of Dresser’s furniture was

produced by Chubbs. Chubbs were, of course, a Wolverhampton firm.

This might be taken as suggesting that Chubbs were another of Dresser's

Wolverhampton links. But the member of the Chubb family with whom

Dresser had contact seems to have lived in London. Chubb's head

offices were in London and they had a safe making factory there;

Wolverhampton was their main manufacturing centre, not the place where

the leading decision makers lived and worked. Although Dresser’s

furniture designs appear in the Chubb Archive it seems most likely that

this furniture making activity was a personal sideline of Mr. Chubb

rather than something which was integrated into the rest of the firm.

And as for Wolverhampton: there was no furniture making tradition there

at all. Chubb furniture must have been made in London. And is

there any evidence of Dresser designs in Chubb’s core business of safes,

locks and keys? There is plenty of scope for such design work but I know

of no evidence, even stylistic, of its having taken place. (The

same might be said for the other great Wolverhampton locksmiths,

Gibbons).

Oliver Wendell Holmes

The most interesting other

evidence of Dresser’s Wolverhampton connection is a brief entry in

Oliver Wendell Holmes’ "One Hundred Days in Europe" (Houghton Mifflin

and Co, 1888), which records his trip round Europe in 1886. Referring to

the window shopping he did in London and commenting on the goods he saw,

Holmes said (p.223): "I greatly admired some of Dr. Dresser’s water-cans

and other contrivances, modelled more or less after the antique .... I

should have regarded Wolverhampton, as we glided through it, with more

interest, if I had known at that time that the inventive Dr. Dresser had

his headquarters in that busy-looking town". That remark raises many

interesting questions but what we get out of it is that Holmes thought

that in about April 1886 Dresser "had his headquarters" in

Wolverhampton.

The only comment I can find on

this is in Stuart Durant’s book, Christopher Dresser, Academy Editions,

1993, where he says (p.39) that "Dresser’s ‘headquarters’ were never, as

far as I know, in Wolverhampton. In 1866 they were at Wellesley Lodge"

and he seems to treat this reference as some sort of misunderstanding by

Holmes. (I might as well note here, as anywhere, that Durant goes on to

say "But what of the watering cans?" In fact Holmes talked about "water

cans" which are quite different).

But Holmes was a careful and

reliable observer and there seems to be no reason for doubting that

Dresser did have his "headquarters" in Wolverhampton. Where Holmes

picked up his information is not clear but somebody gave it to him - and

that somebody would not have meant that Dresser’s offices and studios

were in Wolverhampton but that Dresser was temporarily staying there and

conducting business from there. The reference is not to the idea of the

modern corporate headquarters but to the contemporary military field

headquarters. We know that Dresser travelled about a lot, selling his

services and delivering designs. We also know that he did a lot of work

in and around the Black Country. It would be natural for him to stay for

some while in Wolverhampton whilst visiting manufacturers in that town

and the district. Wolverhampton was the biggest place in the Black

Country, had good rail connections with London and good rail and other

connections with the rest of the Black Country and the surrounding area.

Even Kendricks and Coalbrookdale would have been within reach.

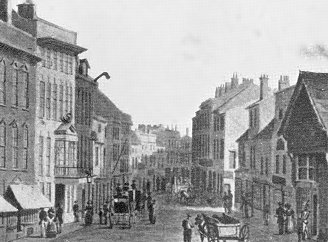

|

The Swan on

High Green (on the left with the balcony and model swan over

it) was a favourite hotel for the many merchants, factors,

salesmen and other commercial people who came in great

numbers to "that busy-looking town".

Much business was

conducted in the hotel and on the pavement of High Green

outside. At the Swan Dresser could have made many

contacts and actually conducted his business. |

It would be interesting to wade

through the local press of the time to see if there are any references

to Dr. Dresser but the foregoing by itself shows that Dresser certainly

had several connections with Wolverhampton; and that therefore we should

not be surprised to find designs by him being produced by Wolverhampton

makers; and, just as much, we should not be surprised to find designs

influenced by Dresser being produced by Wolverhampton makers.

Dresser and Dresserish

designs from Wolverhampton.

Andrew Everett suggests that in

addition to the established case of Richard Perry Son & Co., other

Wolverhampton makers who may have used Dresser designs were John

Marston, Henry Fearncombe, Orme-Evans and Henry Loveridge.

Henry Loveridge

The case of Loveridge has often

been raised (on this web site and elsewhere) but in connection with

artmetalware. Andrew Everett extends the association to Loveridge

designs for japanned ware, which is important not least because it gives

the earliest date – c.1866-68 – for Dresser doing something in

Wolverhampton. This is based largely on finding a page of designs,

in Dresser's style, in one of the books of designs which are said to

have belonged to Henry Loveridge. Even accepting that these books

were the working design books of Henry Loveridge (and the matter is not

absolutely certain), the fact that there is such a limited number of

Dresserish designs amongst all the pages in all the books, suggests that

it was a note of a matter of interest; and the fact that there are no

more would suggest that the interest went no further. The fact

that examples of these designs subsequently appearing on actual pieces

are unknown, does little to re-inforce the idea that Loveridge had

commissioned designs from Dresser.

|

Two jugs by Loveridge, the

"Japanese" jug (right) and an unnamed jug (left), a

variation of the "Dutch" jug. The angular handles are

all that might be associated with Dresser - but they were by

no means his alone. |

|

Loveridge may have noted with

disappointment that only six of his apprentices attended the Art School,

but six informed designers in his company would be a good start.

Loveridge had consistently been represented at exhibitions around the

world and took a close a continuing interest in design which he promoted

and wrote about. I do not see that there is any need for Loveridge

to have engaged Dresser or any other outside designer and do not think

it likely that he did so. The Loveridge catalogue of 1898 refers

to the company as "patentees, designers and manufacturers" - or, to put

it another way, they did their own thing from start to finish. As

designers they may have been influenced by Dresser and, as manufacturers

and designers, they would have designed things in a way which was very

much led by manufacturing considerations - and might therefore end up

with designs like those of Dresser or anyone else operating on that

principle.

|

The "Dutch" jug (left) and the and

an unnamed jug (right). Again the possible Dresser

influence is minimal. Perhaps the squareish handles

are typically Loveridge rather than typically Dresser. |

|

Items of Loveridge’s art

metalware can be found which show some features which may also be found

in Dresser designs – for example, scalloped edges and exposed rivets -

but this is a long way from saying that Dresser designed them. It

may be that Loveridge was influenced by Dresser. Or was it the

other way round?

|

A japanned vase. Note that

this vase, the simple shape of which makes it liable to be

attributed to Dresser, consists of four frustra and is a

typical tinsmith's design. The decoration is quite

unlike anything attributable to Dresser.

Photo by courtesy of

Wolverhampton City Council. |

| The "Parisian" hot water can.

Loveridge's name for this can associates it with the French

watering cans with hooped handles known from the 1820s,

rather than with Dresser. |

|

John Marston

Andrew Everett’s identification

of John Marston as a maker of art metalware, and of the identification

of the pieces he made, was a valuable new development.

|

Photo by courtesy of Andrew Everett. |

Everitt suggests that there is a

possibility that Dresser designed for Marston and he prays

in aid mainly two items. One is a kettle which looks

strikingly like the well known Benham and Froud kettle

in copper and brass – but which is, at best, a variant of it

with a square section spout which seems purely capricious

and which contrast unpleasantly with the rest of the kettle.

The other is a brass jug which is

“extremely similar” to a Watcombe pottery jug – which is

thought, on stylistic grounds, to be by Dresser. |

| This, I think, is an association too

far. It is noticeable that Marston’s jug is a typical

tinsmith’s design – two frustra and a cylinder; only

the handle is not a very natural use of the material.

The oddity is that the Watcombe jug is a ceramic and is not

a natural shape for that material. I would hesitate

slightly before suggesting that the Watcombe design may have

been derived from metalware rather than the other way

round. |

Three variations of

Marston's jugs. |

A wide range of Marston's domestic wares is not

known but it does seem that most of them that are known have quite

strong stylistic associations with Dresser. Martson himself is not

known as having any great personal interest in design

or art but if a second Dresser client, after Perry, is to be found, he

seems to be the best candidate.

|

Marston's ewers are noticeably

squatter than those of other local makers, perhaps

suggesting that Marston did not follow the easy course of

copying other's designs. |

|

Orme Evans

Everett also (in an illustration

from a catalogue) makes a case for Orme Evans possibly being a client of

Dresser. As Orme was a leading light in the 1902 Exhibition, in

which capacity he expressed his concern about the continuing need for

education in good design, he must have been interested in design.

He would have known about Dresser. His designs might have been

influenced by Dresser’s. But there is no evidence to go any

further than that.

Henry Fearncombe

It can be said that Fearncombe

took an early interest in design and exhibited at the big exhibitions.

But so little is known of his products that the association with Dresser

is as tenuous as Orme’s.

|

Chamberstick by Fearncombe.

Although reminiscent of Dresser's work for Perry, this is a

very easy to make design and might have come from any

tinsmith's shop. |

| Water jug by Fearncombe.

Not unlike some Loveridge designs, or the Watcombe vase,

this is a typical tinsmith's design with a wooden handle for

insulation purposes - and which is most easily made and

attached by this right angled system. |

|

|

Water can by Fearncombe. In

so far as it has a reinforcing band, it is right at the top

- not a structurally sound place to put it. The spout

is almost a commonplace but the handle seems to be unique to

Fearncombe.

All three of these items might be

said to be influenced by Dresser. |

Other makers including one

pottery

Other makers of art metalware

seem to show no Dresser influence at all. For example the very large

producers, Sankey, were only down the road at Bilston, but there is

nothing in their currently known products to suggest anything by

Dresser. The other point to make is that Andrew Everett refers to

Loveridge’s japanned wares but all the other possible instances of

Dresser in Wolverhampton are in the area of art metalware. There is not

much point in looking round Wolverhampton for Dresser designs in the

many other types of products which he is known to have designed and

which were probably his major areas of output. To all intents and

purposes there was no manufacture of carpets, wallpaper, glass,

textiles, furniture or ceramics in Wolverhampton.

|

The only possible exception which may

just be worth noting in this context is the remarkable, but

almost unknown, work of the Myatt pottery at Bilston. The

firm seems to have given free reign to a number of designers

and one or two of their productions could, very tentatively,

be seen as Dresserish, particularly if you accept an angular

handle as being symptomatic of Dresser. But the fact

that they had in-house potter-designs rather suggests they

would not have bought in designs. |

| Myatt seem to have produced this studio art pottery from

about 1890 to about 1914, which seems a bit late for Dresser

pottery. But by then the Dresser style may have been

part of the accepted canon. |

|

3. A sort of conclusion

It is as certain as such a thing

can be that Dresser designed for Perry. So Dresser had at least

one connection with Wolverhampton. It is unlikely, though

possible, that he only had one. If we take into account Holmes’s

remark about Dresser’s headquarters, then it becomes somewhat more

likely that Dresser designed for more than Perry alone in the immediate

vicinity. One takes into account also that this was the centre of

production for domestic wares of all kinds, just the sort of thing that

Wallis and other design gurus of the time wanted to ensure were objects

of beauty in every home. Dresser would have had policy reasons and

strong practical reasons to work the area as thoroughly as possible.

It therefore seems likely that

Dresser designed for Wolverhampton maker’s other than Perry. The

only evidence we have is that these may have included Loveridge,

Marston, Orme Evans and Fearncombe. But the evidence is not very

convincing. It can all be explained in ways other than saying that

Dresser designed it.

What I am arguing here may

amount to saying that Dresser was influential. It seems to me that there

has been an unresolved problem in the study of Dresser. After his death

he seems to have been almost immediately forgotten. His name came to

attention again in Pevsner’s 1937 article and after that he became not

much more than a footnote. It is only in the last decade or so that a

number of books and exhibitions have elevated his status and fame. The

argument of these books and exhibitions seems to have been that Dresser

was a brilliant designer. But if he was so brilliant, why did he have no

followers? Why was he not influential? In his time he was financially

successful and some of his designs, at least, must have sold well,

otherwise he would not have got repeat orders. Would that not encourage

imitators? It seems to me to be arguable that the many Wolverhampton

products with Dresserish features show, not that Dresser designed them,

but that he was influential, in his own time, as a designer. To

attribute to Dresser anything which looks in any way like his "new

style" designs is, in effect, to deny that he had any influence on

design.

There is a related problem. Many of Dresser's

design principles arise from an application of principles (such as the

importance of function, of truth to materials, of the influence of

manufacturing meothods) which were espoused and set out before the time

Dresser was at art school and were taught to him while he was there -

and continued to be taught by Wallis and others throughout the

nineteenth century. When we see these principles in practice we

may not be seeing the influence of Dresser but the influence of Wallis

and others.

I say all that subject to this

query: should one say that some Wolverhampton products have

Dresser features on them – or that some Dresser designs have features

from Wolverhampton products on them?

References

The main publications which

relate to Dresser and Wolverhampton are:

Andrew Everett, "Wolverhampton

Japanned Ware" (in Harry Lyons, Christopher Dresser: The People’s

Designer, 1834 – 1904, Antique Collector’s Club, 2005, at pp. 217 – 227)

Andrew Everett, “Christopher

Dresser: the Art and Craft of Design”, Archenfield Decorative Arts

Society, 2006 (the catalogue of the exhibition of the same name at

Hereford Museum and Art Gallery, 20th January to 3rd

March 2007).

Both of those publications deal

with Wolverhampton specifically (as well as with much else). The

other now standard works on Dresser mention Perry but not much else.

|

Return to

Art Metalware |

|