|

Wolverhampton Printers

A short history - page 1

|

|

Wolverhampton’s monastery would probably have had some sort of

scriptorium – a small one where the church's documents could be written

out on parchment. It does

not appear to have been a centre of manuscript production.

The lay people living round about would not have done much

writing – estate accounts and the occasional legal document. All our earliest documents, such as the charters, are

parchment and ink.

Printing was introduced into the country by Caxton in about 1473 and

gradually expanded. But the

presses were tightly controlled by the government and for almost two

hundred years the only places in which anything was printed were London,

Oxford and Cambridge. Their

output was mainly religious texts, classical works and a large number of

law books. During the

disturbances of the 17th century there were periods when many

political tracts were published.

The general expansion of printing beyond the three cities began

towards the end of the 17th century when presses were set up

in many cities and larger towns.

But the type of material they produced remained largely religious,

classical, governmental and legal.

Literacy was not widespread and most towns did not have a

literate population large enough to sustain a printing press.

It was largely economic expansion, the agricultural and

industrial revolutions, which changed the position.

Not only was there a great increase in the population generally,

including great increases in the size of towns, and a general increase

in literacy rates, but there was a commercial and industrial demand for

printed material.

The first book known to have been printed in Wolverhampton was

produced by George Wilson in 1724.

He, and his wife, Mary Wilson who succeeded him, produced a

number of books. This

suggests that they had a pretty good press and a reasonable stock of

type and it is likely that they were finding a sufficiency of commercial

work to be done, even before 1724.

By 1760 another printer, Thomas Smith, is found in

operation and, at the same time Joseph Smart appears on the

scene. He was not only a

printer but an editor and publisher of books, a book seller and a centre

of Wolverhampton’s literary life.

He and his succesors, who included William Parke,

continued printing until about 1833.

As the industrial revolution took a grip in the 19th

century the demand for commercial and industrial printing increased.

Increasing political activity with the widening of the franchise

and with the extension of local government increased the call for

printed material. There was

also a great increase in non-fiction works and the rise in fiction to be

allowed for. Newspapers

started to be regularly published and to flourish from the late 18th

century onwards.

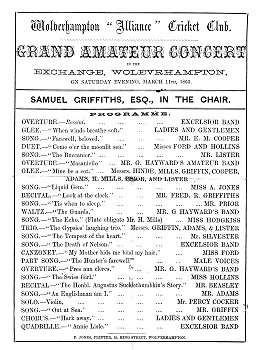

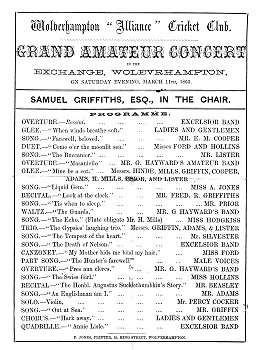

Concert programme by F. Jones, of King

Street. 1863. |

In about 1811 Thomas Simpson appears as a

printer and he seems to have operated on a large scale.

He was succeeded by his son, another Thomas Simpson, who

eventually took into partnership John Steen, who

continued in business under his own name, his firm becoming one

of the largest in Wolverhampton, even taking over Edward Roden’s

business when he retired.

Another printer, whose output also included books, was J.

Bridgen who seems to have been the first to introduce colour

printing to the town.

At what date he did this is not recorded but his first book was

printed in 1831.

Edward Roden seems to have set up his business in

Wolverhampton in 1848.

He not only printed to a higher standard than those who had gone

before him but was a successful inventor of printing equipment. |

| The rapidly expanding town had a rapidly expanding

demand for print of all sorts.

This was met by the expansion of existing firms and the setting

up of new ones.

Alfred Hinde set up in 1856 and became one of the town’s

biggest printers.

But we find references to other printers too during the

latter part of the 19th

century such as A. J. Caldicott, J. Hildreth & Son, Hildreth and

Chambers, J. Heighway, Price and Williams, Richards & Cope, B.

Rowlands, J. A. Roebuck.

Although the bulk of their trade would have been jobbing

printing – printing anything the private customer or the

industrial or commercial customer might want – they would from

time to time print (and possibly bind also) books mostly of the

religious variety, but also some law books, trade directories,

trade catalogues, local guides books, and even slim volumes of

verse. |

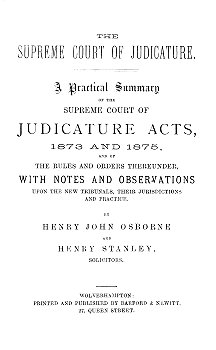

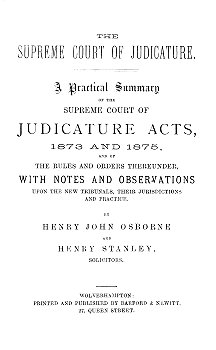

A legal text book, printed

by Barford and Newitt who were at 27 Queen Street. |

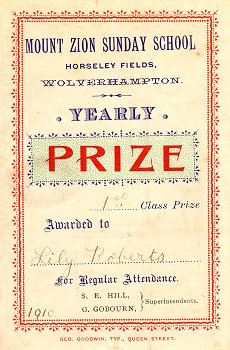

A Sunday school prize book label by

George Goodwin, Queen Street. |

Some of these would have been printed for

booksellers or other sorts of publishers, some for the authors

themselves who would then circulate them however they wished,

but some would be printed for the printer himself to publish.

In times when, if you wanted more than a very few copies of

any written material, printing would be the cheapest and

quickest way to produce them, all sorts of material was printed

– for example, we know that one local worthy, when applying for

a new job, had his cv printed and produced as a book; it is

unlikely that he was alone in this.

But the bulk of their work would be visiting cards, business

cards, letter heads, all sorts of commercial stationery,

posters, commercial and political.

Sometimes they would venture out into printing and publishing

newspapers or magazines; or they would print them for others. |

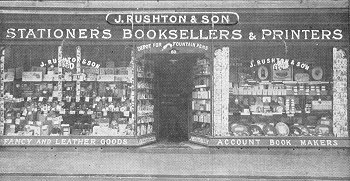

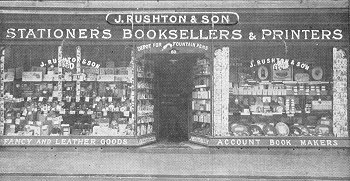

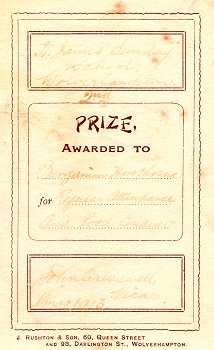

Rushtons shop (it seems to be at 60

Queen Street) shows the range of goods and services which a

local printer, bookseller, book binder and general stationer

would supply. The prize book plate would be a stock item

for the shop. |

|

This seems to be a purpose built printing house.

It is in Wheeler's Fold. Does anyone know anything about it?

Which company operated from here?

|

|

|

|

Return to the

Printing Hall |

Proceed to

page 2 |

|