|

Wolverhampton changed dramatically

as a result of the building of the local canals. In

August 1771 the canal from Birmingham, built by the

Birmingham Canal Company reached Wolverhampton. On 21st

September, 1772 the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal

opened, and four months later the difficult 1½ mile

section from Wolverhampton to Aldersley Junction was

completed.

The new form of transport overcame

most of the problems caused by the inadequate national

road system of the day, and vast amounts of goods of all

kinds were transported to the town. But Wolverhampton

still had its medieval street plan with narrow winding

streets that formed a bottleneck for the many carts and

carriages transporting items into the town, from the

canal.

For many years the town had been in

the charge of the Constables, public executives

appointed by the Manors of the Deanery and of Stowheath,

who had a limited range of duties. Many local

inhabitants were no longer content with their rule, they

wanted changes to be made in the town centre, including

the demolition of old crumbling buildings, a better

water supply, and improvements to the roads.

The

1777 Improvement Act

This led to the first Act of

Parliament relating to the town, the 1777 Improvement

Act for Wolverhampton which appointed 125 Commissioners

to run the town. It started in a small way on Friday

30th May, 1777 when twelve men met at the Red Lion Inn

in North Street to take the first tentative steps

towards local government.

The introduction to the Act

includes the following: “It is a large, populous trading

town and it would be a great convenience to the

inhabitants if the streets were widened where necessary,

and properly cleaned and lighted, and because a

navigable canal has lately been made up in the said

town, the number of carts and carriages used in carrying

and conveying goods and merchandise is greatly increased

and it is essential that they be put under proper

regulations.”

The Act named 125 Commissioners,

all local residents, who were joined by Stewards of the

Manors of the Deanery and of Stowheath, and Prebends of

the Collegiate Church. To qualify for office,

individuals had to own property worth more than £12 per

year and land or goods worth more than £1,000. It was

thought that those with the most expensive property were

the fittest to rule. The Commissioners represented no

one except themselves, they looked after their own

interests.

In June, 1777, they appointed James

Horton as clerk, and agreed to pay him one guinea for

each of their meetings, in return for writing-up the

minutes and ensuring that their orders were properly

carried out. Littleton Powis was appointed as rate

collector, John Marshall as treasurer, and Joseph

Barney, Joshua Devey, and John Smith as assessors.

The meetings were held at various

pubs, including the Hop Pole, the Bird in Hand, and the

Swan, all in the Market Square; the Cock Inn in Berry

Street; the Talbot in King Street; the Angel in Dudley

Street; and the Red Lion in North Street. It was decided

that each Commissioner shall pay not less than sixpence

at each meeting, to be spent in drink for the good of

the house! |

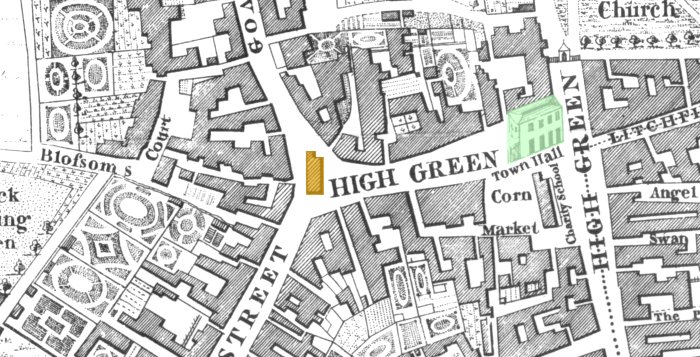

High Green from Isaac Taylor's map

produced in 1750. The market hall is coloured green, and

'roundabout house' is orange. |

| Demolitions and

Street Improvements The

Commissioners were empowered to remove nuisances and

encroachments. One of their first tasks was to demolish

the old Market Hall in High Green which had fallen into

a bad state of repair. It had been built in 1532 and

measured 68ft. by 29ft. 4 inches, and was later known as

“The Old Town Hall”. The upper floor had been used for

the Assizes, and on the ground floor were butchers'

shops and a slaughter house. In the area alongside the

building, known as the shambles, skins of slaughtered

animals were left on the ground in a filthy and

disgraceful condition. The building was demolished in

1778, and the butchers’ shops and the shambles were

moved, after some opposition from the traders, to Pigstye Walk, alongside St. Peter’s churchyard. After

the work had been carried out, the market place was much

cleaner and healthier.

People were forbidden to ‘wash any

brass dirt or ashes, or any kind of metal’ in the

streets, for which there was a fine of ten shillings,

and stall owners in the market place and the surrounding

streets were to ordered to remove their stalls before

twelve o'clock at night on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and

before ten o’clock on other nights. Scavengers were

ordered to go round once a week and inform the

inhabitants of their approach, using a loud bell or

shouting. Their job was to collect ashes and rubbish

from places that were inaccessible to carts, such as

yards at the back of houses. A fine of five pounds was

introduced for anyone involved in bull or bear baiting,

and a fine of twenty shillings was to be paid by anyone

who slaughtered any animal in the streets. Properties

with an annual value of four pounds, and not exceeding

seven pounds were rated at 4 pence in the pound, and

properties with an annual value of seven pounds, and not

exceeding fourteen pounds and six pence were rated at

one shilling in the pound.

The Commissioners then turned their

attention to the dark, crooked, narrow, and dangerous

streets. Oil lamps were hung on street corners, and

every ale house was ordered to fix a lamp over the door.

Although the illumination from such lamps was at best

dismal, it was the only option. Gas supplies did not

exist at the time.

Some of the people who lived in the

more narrow streets, received an order to demolish the

porch on the front of their house because it was seen as

an obstruction. The Commissioners ensured that all the

streets were named, using white letters six inches high

on a black background. At the same time all the houses

and buildings were numbered. They also decided that

something had to be done to improve the town’s water

supply. The waterworks were totally inadequate, and so

the lack of supply was partly remedied by the sinking of

wells around the town centre, at places including Town

Well Fold; High Green, Salop Street, Snow Hill, North

Street, Bilston Street, Walsall Street, Stafford Street,

and the Culwell near Cannock Road. |

|

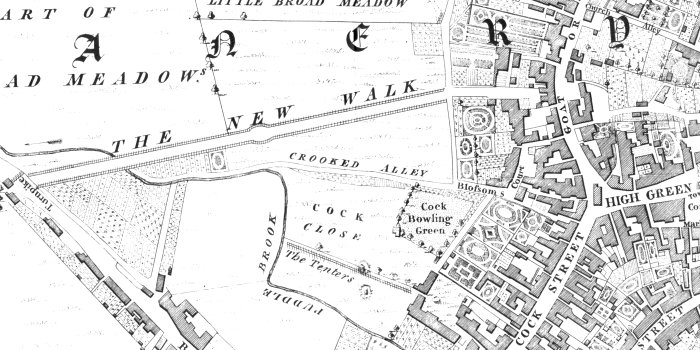

The western side of the town

before the building of Darlington Street. From Isaac

Taylor's map. |

| More Improvements

The problem of the inadequate water supply was discussed

during a Commissioners’ meeting at the Cock Inn in

August 1779. At the meeting the treasurer was instructed

to pay Mr. Bowick £1.4s.8d. for taking the levels of

springs at Goldthorn Hill; and Mr. Junett was paid £29

for supplying a water cistern, 18 feet wide and 35 feet

long, which stood in the market place, and also for

repairing some of the other waterworks in the town.

Unfortunately the water supply was still inadequate, and

so some residents sunk wells in their back garden to get

a better supply than could be obtained from the public

wells. Also in 1779 Samuel Salt was appointed as parish

beadle.

The Commissioners also considered

the possibility of providing suitable stalls on market

days, in the market place. It was agreed that Mr. Higgs

could erect stalls at his own expense and charge one

penny for each separate basket brought into the market.

Later they agreed that he could rent the ground

previously occupied by the market hall, and the now

demolished water cistern, for seven pounds ten shillings

annually for ten years.

In 1793 the Commissioners decided

to divide the town into ten districts, and employ extra

scavengers to clean the streets. They also entered into

a contract for lighting the town’s streets, and improved

policing by appointing a watchman for each district to

control crime, particularly because there were frequent

robberies with violence, especially at night. Each

watchman had a watch box to shelter in, and was dressed

in a heavy fawn coloured coat, with a cape, and provided

with a dim horn lantern, a large wooden rattle, and a

long stave. Every half hour they would leave their watch

boxes for a few minutes to call the time, and the state

of the weather.

The Town Improvement Act of 1814

banned the use of thatched roofing, although the last

thatched building in the town, a cottage in Broad

Street, remained until the 1870s. In order to improve

the state of the streets, the Commissioners ordered that

every person should clean the area in front of his or

her house before 10 o'clock on every Thursday and

Saturday morning, and that some of the poor men from the

workhouse should sweep and clean the streets.

Darlington Street

Another old building, seen as a roadside obstruction

was the ancient ‘roundabout house’ that stood at the

western end of High Green between North Street and Cock

Street (now Victoria Street). It was in a dilapidated

and dangerous state, and in May 1815 was sold to the

Commissioners by Sam Adey, the owner, for £800. The

building was soon demolished. The materials from the

building were sold by auction to the highest bidder.

When the building had gone, the Commissioners decided to

build a new street from the western end of High Green to

the bottom of Salop Street. They approached the land

owner Lord Darlington and agreed to purchase the land

for £350 per acre. The new street became Darlington

Street. |

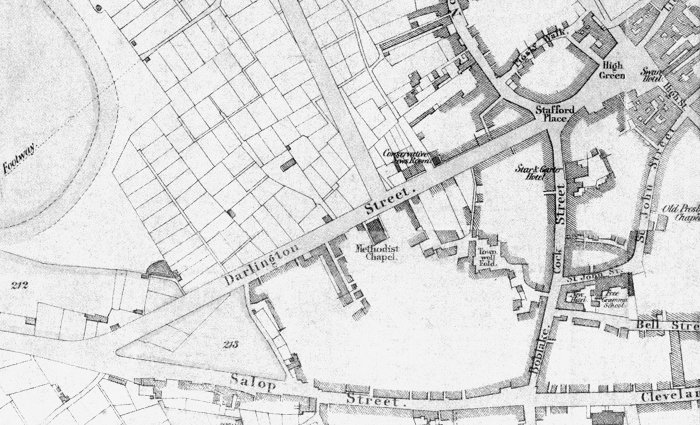

|

The newly built Darlington Street.

From the 1842 Tithe map. |

|

The big candlestick in High Green. |

As already mentioned, the streets were originally

lit with totally inadequate oil lamps. This situation

was rectified in 1821 when for the first time the

streets were lit by gas.

The town’s gas supply was provided by the

Wolverhampton Gas Company, and produced at the gas works

that were built in Horseley Fields, and began production

on 17th September, 1821.

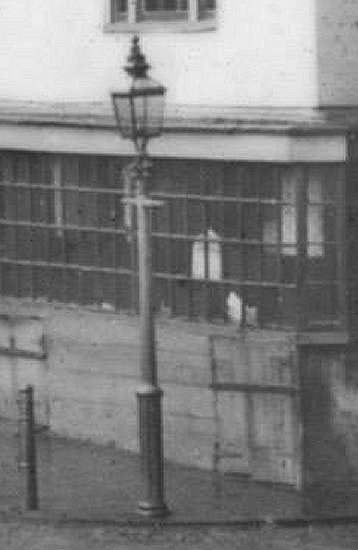

The gas lights were a great success, and a large cast

iron column about fifty feet high, carrying a huge gas

lamp, was erected in High Green to commemorate the

event. Because the column was so high, the light did not

reach the ground, and it became known as ‘the big

candlestick.’

By 1826 the pillar of the lantern and the railing

round its base became dirty, and the surrounding area

was a rendezvous for the local layabouts and

degenerates.

It became a public nuisance and was eventually

removed in 1840. In 1824 the gas company renewed the

contract for lighting the streets at a cost of £1.16s.

per lamp per year. |

|

A gas lamp in High Green. |

|

A typical gas light. |

|

Waterworks

The Commissioners supported a Bill

for the formation of the Wolverhampton Waterworks

Company to supply the town with water. The waterworks

company was formed in 1845 and a new waterworks was

built in Regis Road, Tettenhall. Up to 800,000 gallons a

day were pumped from boreholes and stored in reservoirs.

The Commissioners also gave their support to a Bill to

provide a new cemetery, which led to the building and

the opening of Merridale Cemetery in 1850.

Dissatisfaction and Change

By the 1840s there was a great deal

of dissatisfaction with the Commissioners. The question

of a network of sewers for the town attracted much

attention, but the Commissioners’ borrowing was limited

to £20,000 so nothing was done. People were also

dissatisfied because the Commissioners were not elected

by the ratepayers and could choose anyone they wanted,

to fill their vacancies. They also appeared to work

extremely slowly. Other dissatisfactions included the

incompetent watchmen, beadles, and parish constables,

who were all open to bribery.

Dissatisfaction grew, and on 1st

February, 1847 a petition was signed by 108 of the

principal householders, and presented to Mr. John

Hartley, the Head Constable, asking him to call a public

meeting to consider the possibility of petitioning

Parliament and the Queen to ask for the granting a

Charter of Incorporation for the town. As a result of

the successful application, the Commissioners were

replaced by a Borough Council in 1848. The first council

elections were held on 12th May, 1848.

One of the Commissioners’ last acts

was the purchase of a large piece of land beside

Cleveland Road from the agent of the Duke of Cleveland,

for the construction of a cattle market for the sale of

horses, cows, sheep, and pigs.

References:

The Book of Wolverhampton by Frank

Mason. Pub. Barracuda Books Limited, 1979.

Wolverhampton The Town Commissioners by Frank Mason.

Pub. Wolverhampton Public Libraries, 1976.

The Story of the Municipal Life of Wolverhampton by W.

H. Jones. 1903. |

|

|

Return to the

previous page |

|