|

Many Victorians were justifiably proud

of their country’s achievements, both at home and abroad.

Numerous people were art lovers, and there was great pride

in our vast manufacturing industries and their world-beating

products. The success of the Great Exhibition at

Crystal Palace in 1851 led to many similar exhibitions, on a

much smaller scale, taking place throughout the country.

Entrepreneurs were always ready to promote such events,

which were usually very profitable.

Wolverhampton had its share of

exhibitions, most of which were very successful. The first,

organised by George Wallis in 1839 was held at the

Mechanics’ Institute in Queen Street. Another held in the

grounds of the Molineux Hotel in 1869 was equally

successful, as was one in 1884, held in a temporary building

on land in Wulfruna Street, where the wholesale market later

stood (now the Civic Centre) to raise funds for

Wolverhampton Art Gallery, and the School of Art.

The inspiration for an art and industry

exhibition in Wolverhampton possibly came from the 1901

Glasgow International Exhibition upon which much of it seems

to have been based. The Glasgow exhibition had displays of

fine art in the City’s new art gallery, a highly ornamented

industrial hall for industrial exhibits, exhibitions

featuring countries with close ties to Glasgow, and

entertainment, including a switchback railway, and a water

chute. It was extremely successful, attracting around 11.5

million visitors.

Much of the inspiration for the

Wolverhampton exhibition came from Dunfermline born Thomas

Graham, proprietor of the Express & Star newspaper, and

prominent Liberal councillor. Interest was shown by local

industrialists, businessmen, and the town council. There

were many people willing to finance the project, which was

seen as a sure way of making money. It was to consist of an

art display in Wolverhampton art gallery, and industrial

displays and entertainment on land near to Newhampton Road

East, and in West Park, to allow easy access from the town

centre.

|

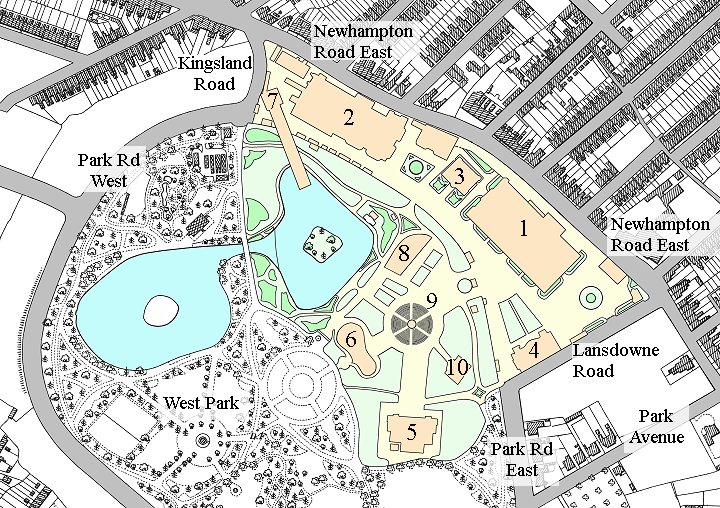

A map of the exhibition site based

on the map produced by Whitehead Brothers. The main

features are as follows:

| 1. |

Industrial Hall |

6. |

|

Spiral Toboggan |

| 2. |

Machinery Hall |

7. |

|

Water Chute |

| 3. |

Canadian Hall |

8. |

|

Voyage Through Fairyland |

| 4. |

Connaught Restaurant & Shell

Bandstand |

9. |

|

Kiosk Bandstand |

| 5. |

Concert Hall |

10. |

|

Magic Mirrors |

|

|

A bird's eye view of the

exhibition by George Phoenix. From Hildreth &

Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Building work on the large impressive

buildings started in 1901, after a competition was held for

the design. The winners were two Glasgow architects, Robert

Walker and Thomas Ramsey, who designed the three main

buildings; the Industrial Hall, the Machinery Hall, and the

Canadian Hall. The largest building, the Industrial Hall

was 107 metres long by 52 metres wide with three bays for

displays by British manufacturers. The slightly smaller

Machine Hall measured 107 metres long by 40 metres wide. It

also had three bays. The smallest of the three buildings,

the Canadian Hall, was paid for by the Canadian

Government and featured attractive displays about the

country, hopefully encouraging would-be immigrants from the

UK.

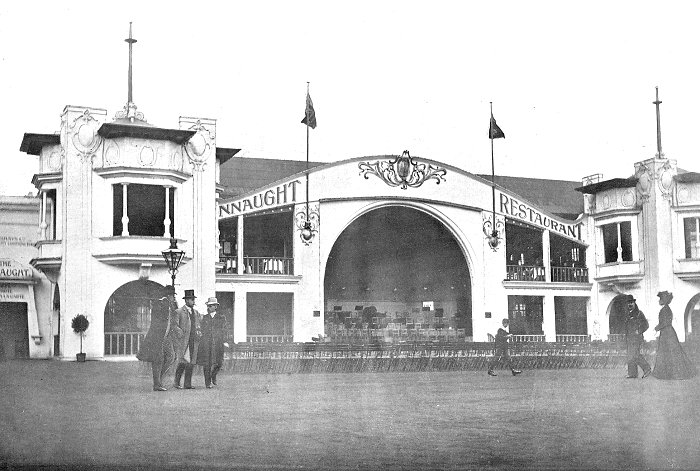

The two other major buildings were the

Concert Hall, and the Connaught Restaurant and Shell

Bandstand. The building contractors were James Herbert of

Hartley Street, and Henry Gough of Dudley Road. Smaller

buildings included the Barnard Popular Restaurant, several

small restaurants and tea rooms, and a number of small

structures built to house displays by local companies.

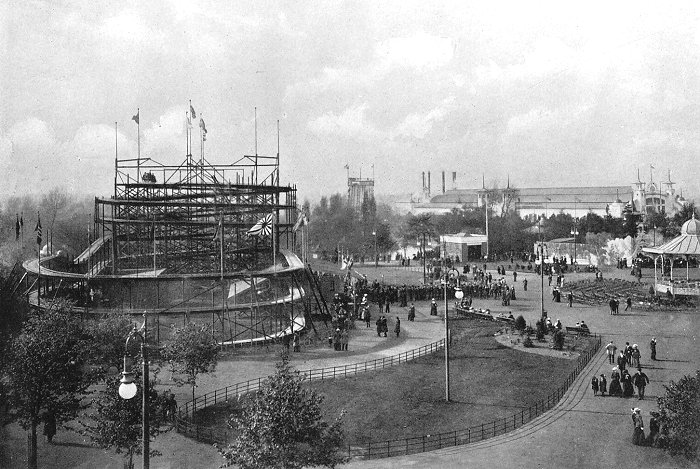

Amusements included the small kiosk bandstand, the water

chute, the spiral toboggan, the voyage through fairyland,

and magic mirrors. The buildings occupied the north eastern

corner of West Park and an area between Park Road East and

Newhampton Road East. A section of Park Road East was closed

to make way for the exhibition.

|

|

Because the local authority expected a

very large number of visitors to the exhibition, underground

toilets were built in Queen Square, and the council ensured

that the new electrically-powered trams would be up and

running between Whitmore Reans and the town centre to

provide easy access to the site.

The art displays in Wolverhampton Art

Gallery were planned by the Fine Art Committee, under the

chairmanship of Laurence Hodson. The committee consisted of

John Annan, John F. Beckett, Thomas B. Cope, Edward L.

Cullwick, Edward Deansley, A. C. C. Jahn (Director of the

art gallery), Charles Paulton Plant, J.P. (mayor of

Wolverhampton), H. G. Powell, W. S. Rowland, Thomas H.

Sidney, Ernest White, R. Williams, and Thomas Wilson.

The paintings and sketches included

works by John Constable, Sir Joshua Reynolds, William

Hogarth, Thomas Gainsborough, Van Dyck, J. M. W. Turner,

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Horatio McCulloch, William

Strang, D. G. Rossetti, Rembrandt, Edward Burne Jones, and

many others.

|

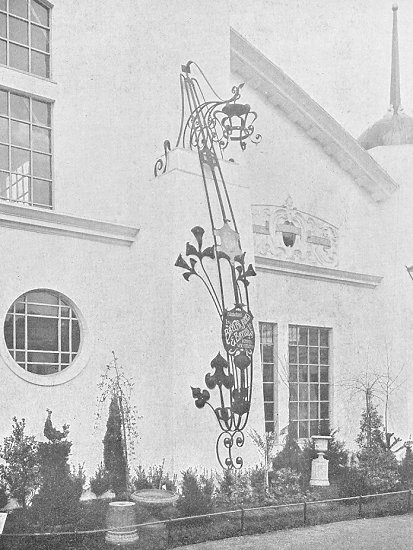

An ornate light fitting on the front

of the Machinery Hall. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of

the exhibition. |

|

Many important artworks

were on display at the exhibition.

Duncan Nimmo has kindly sent the

following assessment of the art section,

that came from an article about William

Strang in the journal “Studio” from

1921.

Between 1899 and 1901 Strang painted the

ten canvasses with which he established

a place for himself amongst the English

painters of the day. This series, to be

mounted in panelling as a frieze, was

dedicated to the theme of Adam and Eve

and commissioned by an enlightened

collector and patron, the Wolverhampton

brewer, Laurence Hodson. It was in this

series that Strang first managed to

correlate a sympathetic code of

colouration with his established ability

to compose in the classic and massive

manner. Amongst those critics and

painters who felt that the decorative

and insubstantial aspects of French

Impressionism and bravura painting had,

via the N.E.A.C., gained too much of a

hold over young English artists, such

works were welcome.

The critic, Frank Rutter, later wrote

that ‘amongst the exhibitions of 1902, I

pick out as the most representative that

held in Wolverhampton. This I shall

always couple with the first

International Society as the two

exhibitions of modern art which have

most deeply stirred me, and while the

International thrilled me by its

Whistlers and its modern French

painting, it was at Wolverhampton that I

was first roused to consciousness that

there and now, all around me, was

growing up a really great school of

British painters . . . the sensational

feature of the exhibition was a room

devoted to the younger and intenser

artists of the day.’

Amongst these

artists, Wilson Steer, Tonks, Orpen,

Rothenstein, Nicholson, Holmes, Shannon

and John, he made specific mention of

Strang's Adam and Eve series. These were

noticeable also as amongst the very few

large scale religious and mural

paintings (always associated in the

English mind with attempted

nationalistic revivals of an indigenous

school of the date.) |

|

| The exhibits in the Industrial Hall

consisted of displays by British manufacturers, including

ironwork, safes, silverwork, glass, upholstery, paint,

bicycles, and even a display by Heinz, featuring soups,

baked beans, and tomato sauce, which visitors could sample. Other items on display included cycles by Beau Ideal, and Wulfruna; safes by Chubb, and George Price; locks and door

furniture by James Gibbons; fencing and gates by Bayliss,

Jones & Bayliss; and gears by John Roper. There were also

some exhibits from abroad including carvings from India, and

arts and crafts from Japan. |

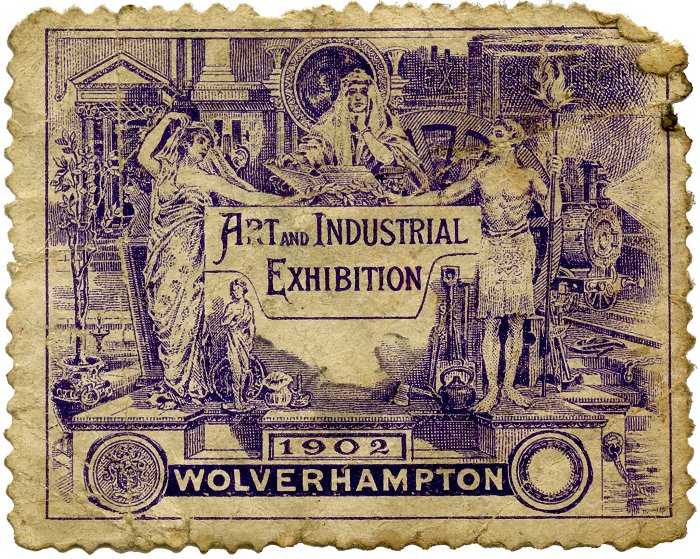

One of the special stamps that

were produced to commemorate the exhibition.

Courtesy of Ralph Hickman. |

Another of the special

stamps that were produced to commemorate the

exhibition. Courtesy of Ralph Hickman. |

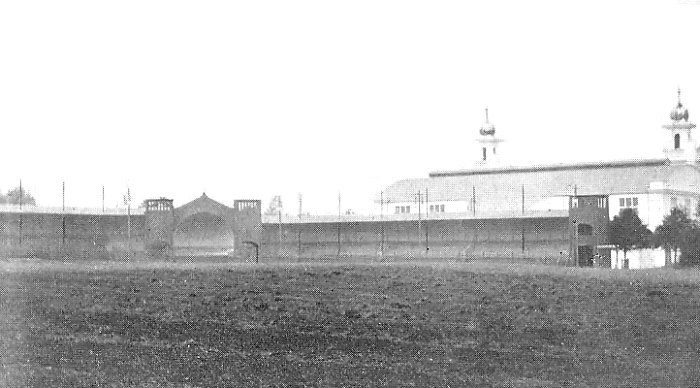

Wolverhampton Art Gallery where

the fine art section was on display. From H. J. Whitlock

& Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

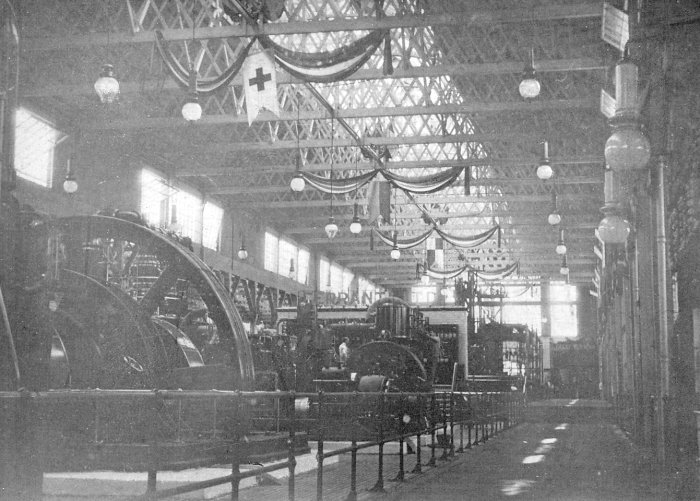

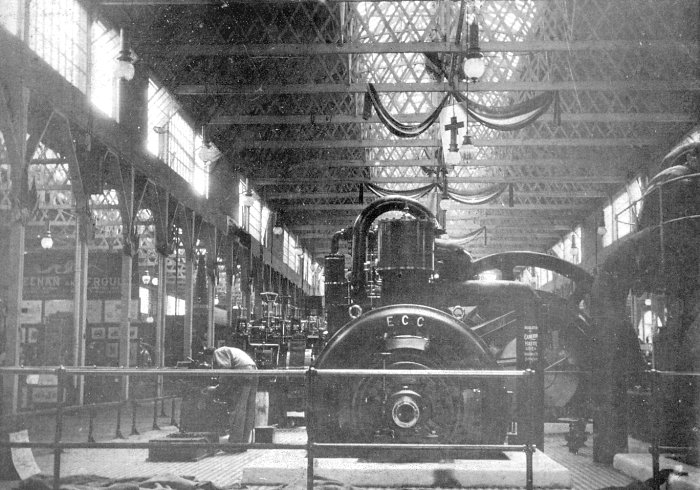

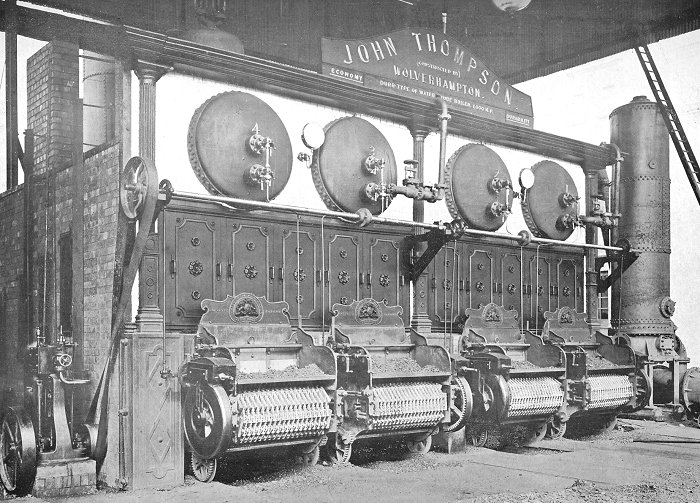

In the Machinery Hall visitors could

see impressive displays of a wide range of machinery,

including motors, printing machines, weaving machines, and

the boilers and generators that were supplying the

electricity for the exhibition. Displays included electric

motors and generators by E.C.C.; boilers by John Thompson;

and pumps by Joseph Evans.

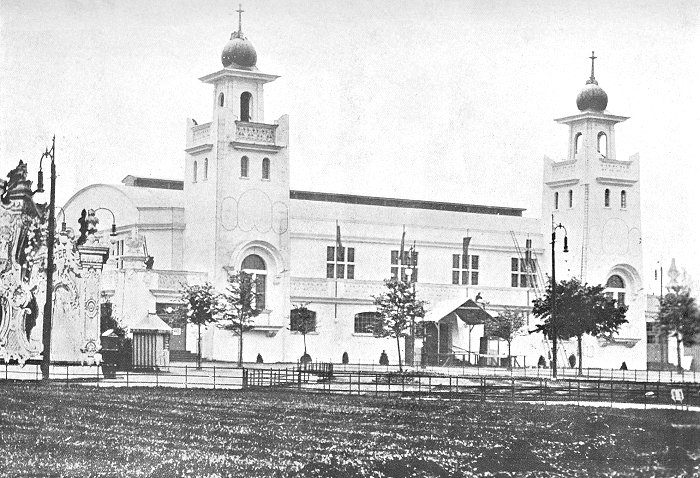

In the Canadian Hall were displays

featuring the country’s natural resources, including

minerals, gold ore, clay, timber, and agricultural goods

such as meat, fruit, whisky, butter, cheese, eggs, grain,

grasses, and canned goods. There were also displays of

photographs, and landscape paintings.

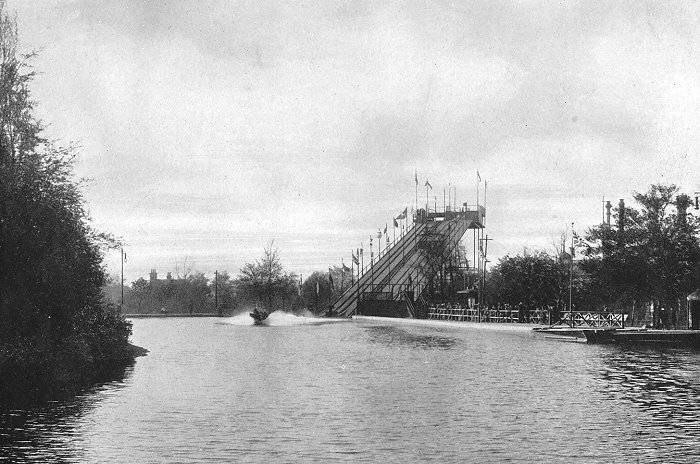

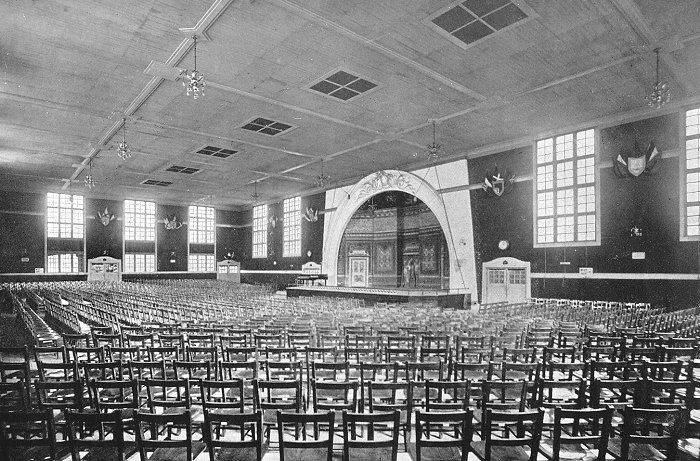

Entertainment in the Concert Hall

included orchestral concerts, recitals, and even a ping-pong

tournament. Outdoor entertainment included the five storey

spiral toboggan, the first of its kind in the country; the

water chute, the first one in the Midlands; the kiosk

bandstand, and a small fire station. There was also the

voyage through fairyland; and the magic mirror building with

its ‘hall of laughter’ with twenty five mirrors.

|

The fine wrought iron railings and

gates at the main entrance in Lansdowne Road. They were

manufactured by Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss Limited. From

Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

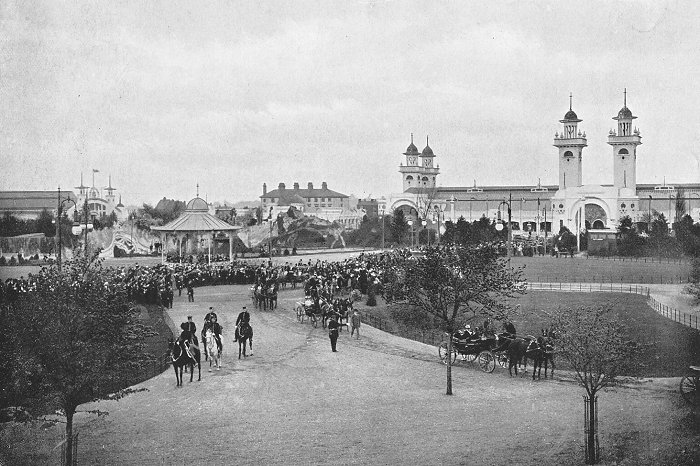

The exhibition opened on 1st May, 1902.

The president was the Earl of Dartmouth. The official

opening was carried out by the King’s brother, the Duke of

Connaught, who arrived at the High Level Station on a

special train along with a party of guests including the

Duchess of Connaught, and the mayor of London and his

sheriffs. They travelled to the exhibition after a brief

stop at Wolverhampton Art Gallery where they were greeted by

the mayor of Wolverhampton, Councillor Charles Paulton

Plant, before inspecting the fine art exhibits.

The carriage then made its way to the

industrial part of the exhibition via Queen Square, where

the new toilets were covered in red cloth to hide them from

the royal party’s view. They then proceeded via Darlington

Street, Waterloo Road, and Newhampton Road East. They

arrived at the exhibition and were welcomed in the Concert

Hall where speeches were given, and the exhibition was

declared open. At three o’clock they arrived at the

Industrial Hall where a gold key was handed to his highness,

who proceeded to unlock the front door. After viewing the

hall, the party visited the Canadian Hall where they were

received by Lord Strathcona, followed by an inspection of

the Machinery Hall, and a walk around the site. Around four

o’clock they entered the refreshment rooms for a rest before

returning to the railway station to catch their train. That

evening there were illuminations in the town and at the

exhibition.

|

The arrival of the Duke & Duchess

of Connaught. From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic

souvenir of the exhibition. |

The arrival of the Duke & Duchess

of Connaught at the Concert Hall. From H. J. Whitlock &

Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

The opening ceremony. From H. J.

Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

| One local celebrity who visited the

exhibition was Colonel Tom Thorneycroft, the eccentric owner

of Tettenhall Towers. On seeing the great water chute, he

couldn’t resist having a go. The 81 year old was greatly

shaken by the buffeting during the descent, so much so that

he became ill. Sadly he never recovered, and died on 6th

February, 1903. |

|

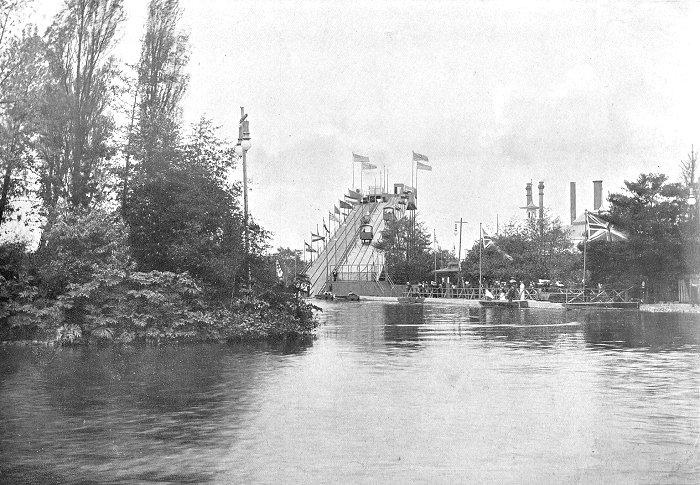

The water chute. From H. J.

Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

The exhibition, although

Wolverhampton’s grandest display, failed to attract the

expected number of visitors. One factor must have been the

poor summer, which was cool and unsettled. That year there

were three major volcanic eruptions, one at Martinique,

another at Guatemala, and a third in Mexico, which reduced

the solar radiation between 10 and 20 percent. Rail travel

was also quite expensive, so many people would have been

reluctant to travel a great distance to the event.

Although 245,000 people attended on the

first day, and around 1.5 million attended over a period of

six months, the exhibition made a loss of £30,000 which

equates to over £3 million in today’s money. By November the

subscribers had had enough. The exhibition closed on 8th

November, even though there were calls to reopen it in the

following year. It was a sad end to such a prestigious and

ambitious event, which initially attracted so much interest.

During the next few months everything

was sold at auction. Thomas J. Barnett & Sons, auctioneers,

produced a catalogue listing everything from the buildings

to their contents. By the end of 1903 the site must have

looked much the way it did before the exhibition was

planned. One of the sale items became the once well-known

Swiss chalet bus shelter in Wergs Road, Tettenhall, which

was eventually replaced by a modern structure.

|

|

The Industrial Hall. From Hildreth

& Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the Industrial

Hall. From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir

of the exhibition. |

|

The interior of the Industrial

Hall. From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir

of the exhibition. The stand next to Wulfruna Cycles was

occupied by Charles Clark, carriage maker of Chapel Ash. |

|

Another view of the interior of

the Industrial Hall. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir

of the exhibition. |

|

The George Price display of safes

in the Industrial Hall. From Hildreth & Chambers

souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

A final view of the interior of

the Industrial Hall. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir

of the exhibition. |

|

An external view of the

Industrial Hall, from an old postcard. Courtesy of

Craig Denston. |

|

The Machinery Hall. From Hildreth

& Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the Machinery

Hall. From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic

souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

The interior of the Machinery

Hall. From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir

of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the interior of

the Machinery Hall. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of

the exhibition. |

|

A final view of the interior of

the Machinery Hall. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of

the exhibition. |

|

The John Thompson boilers in the

Boiler House. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

The Canadian Hall. From H. J.

Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the Canadian Hall.

From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

The Concert Hall. From Hildreth &

Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the Concert Hall.

From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

The interior of the Concert Hall.

From H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

The Shell Bandstand and Connaught

Restaurant. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

The Connaught Restaurant. From

Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

Looking towards the Machinery Hall

with the Industrial Hall on the right. From Hildreth &

Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

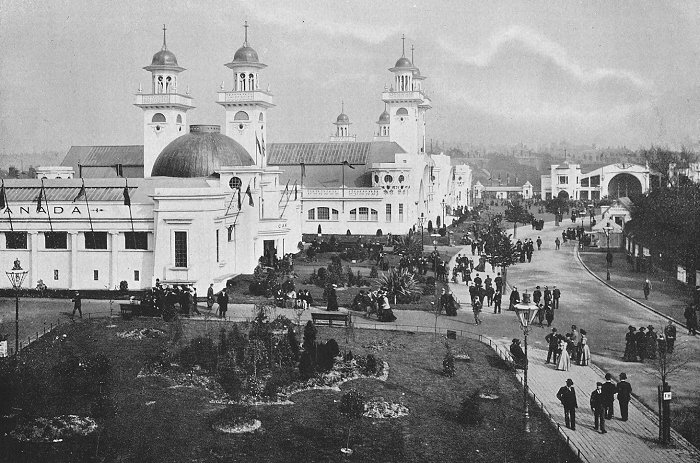

Looking eastwards towards the

Shell Bandstand and Connaught Restaurant. On the left is

the Canadian Hall with the Industrial Hall behind. From

H. J. Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

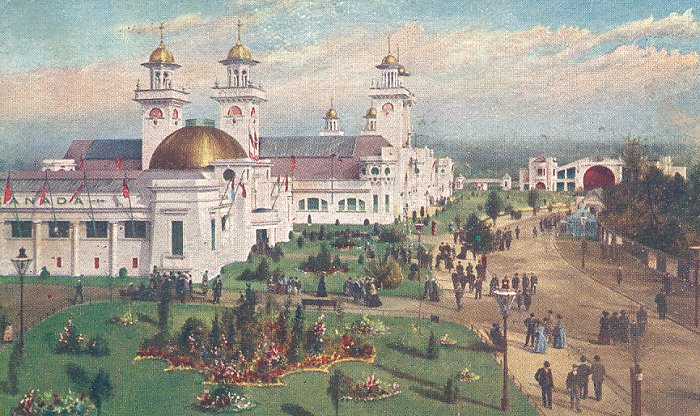

A hand-coloured version of the

previous image. From an old postcard. |

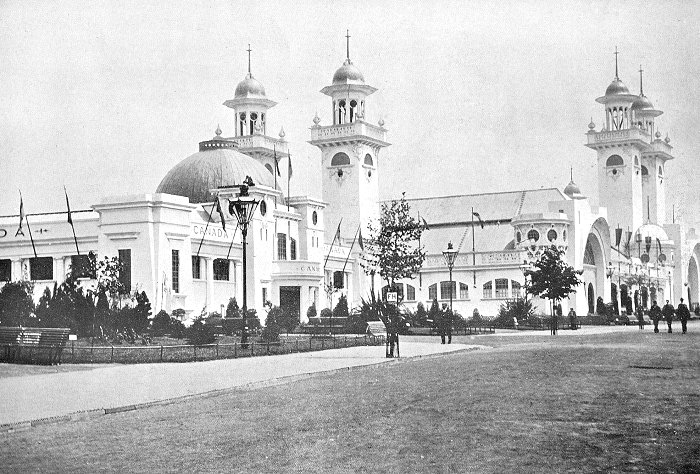

Another view looking east with the

Canadian Hall on the left and the Industrial Hall on the

right. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

Looking westwards towards the

Water Chute from near the main entrance. From H. J.

Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

The Industrial Hall from West

Park. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

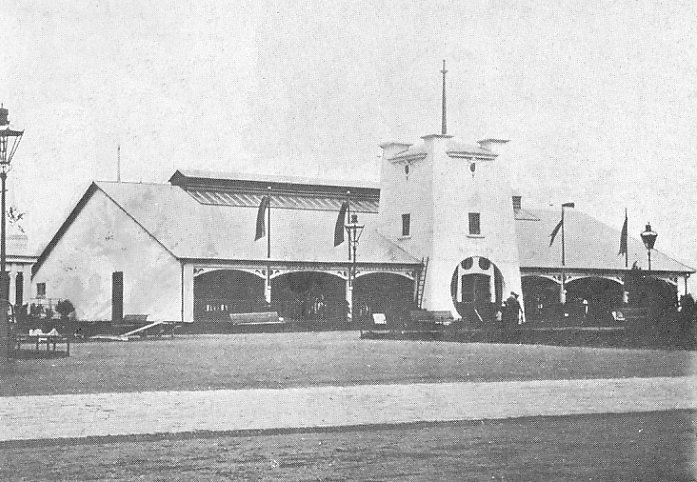

The Barnard Popular Restaurant.

From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

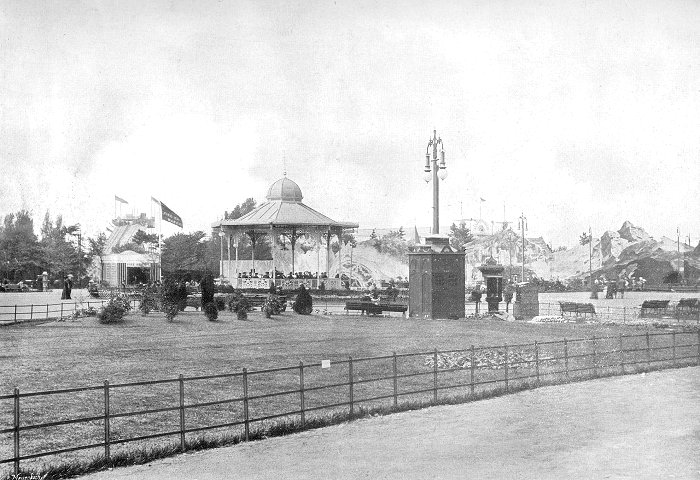

The Kiosk Bandstand with the

Industrial Hall on the left. From H. J. Whitlock & Sons

photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

The Kiosk Bandstand with the Fire

Station to the left, and the Voyage Through Fairyland on

the right. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

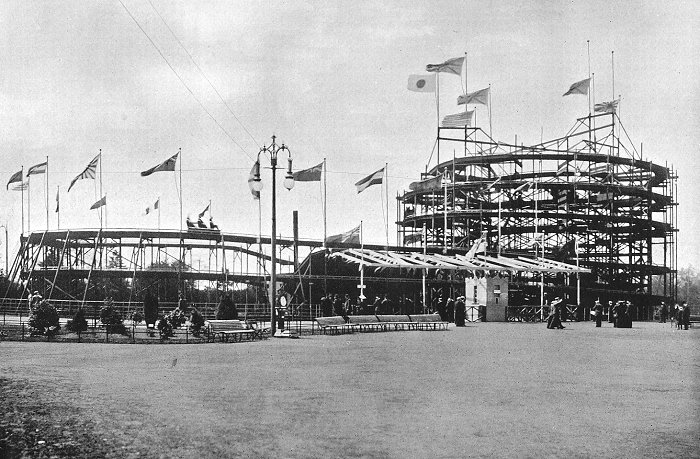

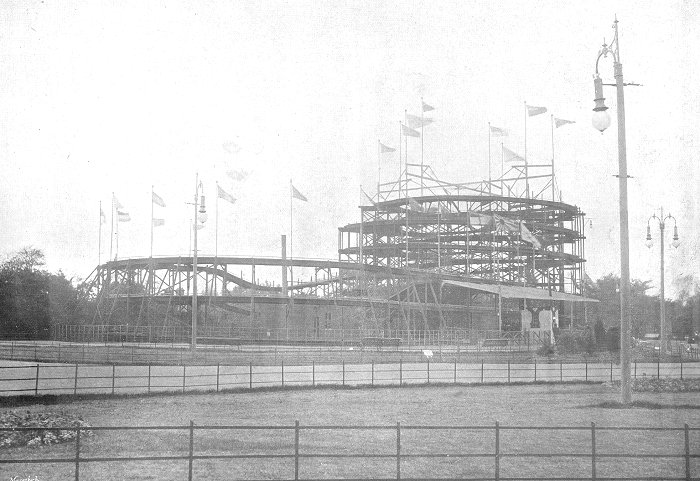

The Spiral Toboggan. From H. J.

Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the Spiral

Toboggan. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

A final view of the Spiral

Toboggan with the Water Chute behind, and the Machinery

Hall in the distance on the right. From H. J. Whitlock &

Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

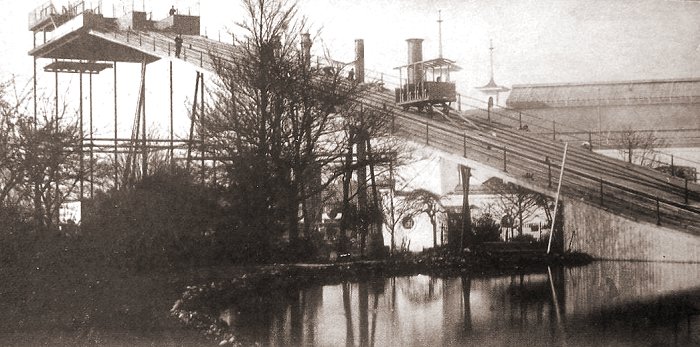

The Water Chute. From Hildreth &

Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Another view of the water

chute. From an old postcard. |

|

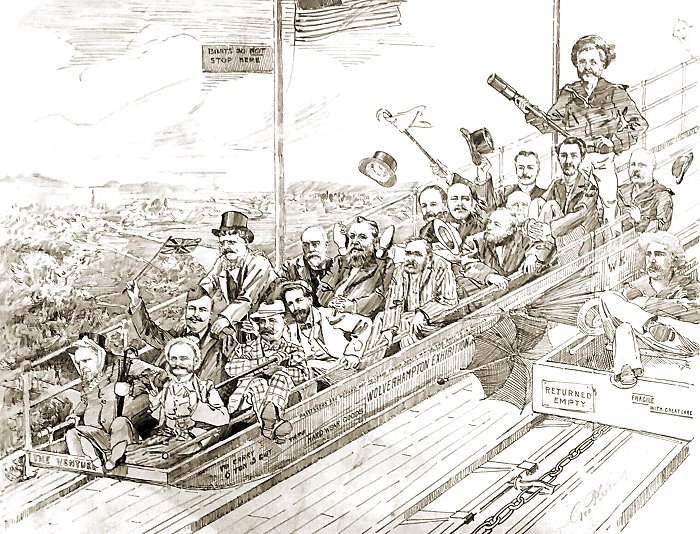

A drawing of the water

chute by George Phoenix. |

|

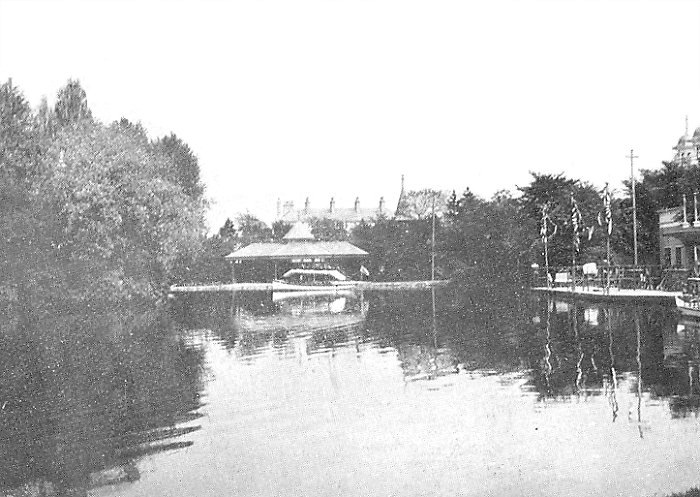

Swan boats on the lake. From H. J.

Whitlock & Sons photographic souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

An electric launch on the lake.

From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

Some of the outside exhibits. From

Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the exhibition. |

|

The Tournament and Firework

Ground. From Hildreth & Chambers souvenir of the

exhibition. |

|

A commemorative ash tray.

Courtesy of David Parsons. |

|

The underside of the ash tray.

Courtesy of David Parsons. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|