|

The

Sage At Badger.

John Ruskin's Visits to Shropshire, 1850 & 1851.

by Anne Amison.

In January 1850, Mrs Euphemia (Effie) Ruskin, of

London, paid a visit to the home of Colonel Edward

Cheney, of Badger Hall, near Albrighton, Shropshire. The

Colonel was away, as the visit was paid in Venice.

Effie, aged 21, was spending several months in Venice

with her husband. John Ruskin, at 31, was already a

respected critic and author on art and architecture,

having published the Seven Lamps of Architecture in

1849. John was in Venice to research his new book, The

Stones of Venice. |

| Effie Ruskin drawn

by G. F. Watts in 1851. |

|

|

John Ruskin in his thirties. |

| Effie was left to her own devices during the day,

whilst John sketched, measured and took plaster casts of

Venetian arches, windows and pillars. One day her

friend, Rawdon Brown took her to the palatial apartment

in Palazzo Soranzo, overlooking the Grand Canal,

belonging to Colonel Edward Cheney. Although the Colonel

was not there (he visited Venice once a year), Effie was

entranced by his "mixture of Italian and English

comforts" and by his collections of gems, statues,

pictures "and I don't know what".

Palazzo Soranzo.

On the Ruskin's return to London, Effie

was glad of the opportunity to meet Col. Cheney and his

elder brother Robert, an artist, at their London home in

Audley Square. (There was also a younger brother,

Ralph). Effie soon became a friend of the three

scholarly brothers, who were great collectors of

classical antiquities which they displayed in a small

museum at Badger Hall. The brothers invited Effie and

John to pay them a visit at Badger Hall, and the Ruskins

stayed for a few days in August 1850.

Badger Hall had originally been a timber-framed medieval

manor house. This building was demolished in 1719 and

replaced by a house offering more modern comforts

including a drawing room, smoking room and "best

parlour".

Between 1779 and 1783 the owner, Isaac Hawkins Browne,

MP for Bridgnorth, added a spacious extension, turning

Badger Hall into a stone-framed, brick built house with

a library, conservatory and museum complete with moulded

plaster friezes showing gods, heroes and characters from

Shakespeare. A surviving sketch shows a comfortable,

commodious Georgian home. |

|

Badger Hall, from the Victoria

County History, Salop. |

The architect of the extension, James Wyatt, was

also engaged by Isaac Browne to build a summer house in

the style of a Greek temple between the formal gardens

of the Hall and Badger Dingle. This well-known local

beauty spot is not, as most people now believe, a

natural landscape: it was deliberately "improved" in

1780 as a "wilderness", a wild garden with a stream,

hills and valleys. |

| Making artificial "romantic" landscapes for walks

and picnics was very popular among Georgian country

house owners: Lizzie Bennet and Lady de Bourgh walk in

"a prettyish kind of a little wilderness" at Longbourn

in Pride and Prejudice. The wilderness was an

interesting yet safe environment for walks, sketching

and dalliance. Should a picnic be planned, the servants

had only a short distance to carry the rugs and tea

service. |

So what would John Ruskin, the well-known

architectural critic, think of Badger Hall? The answer

is: he would probably dislike it intensely! He made his

visit there with considerable reluctance: Mr Ruskin did

not like socialising as it kept him from his work; and

we know from one of Col. Cheney's letters that the

brothers thought less highly of John than of Effie:

Mrs Ruskin is a very pretty woman and is a good deal

neglected by her husband, not for other women but for

what he calls literature…. but I cannot see that he has

either talent or knowledge. (August 1851)

This opinion may well have been formed during Mr and Mrs

Ruskin's visit to the Hall. |

| Wyatt's Greek

temple overlooking Badger Dingle. |

|

| The museum at

Badger Hall (Victoria County History,

Salop). |

|

The Cheney brothers were no doubt proud of their

Georgian country home, inherited from their

childless cousin Isaac Browne. They were proud of

their museum, a photograph of which (taken in 1888)

shows paintings, busts of Roman Emperors and a

medieval seat with gilded arm-rests featuring winged

lions: the symbol of Venice. |

| With the exception of the medieval seat, all of

this would have been anathema to John Ruskin. He

would loathe everything around him: the Georgian

house with its rectangular sash windows and

classical pediment; the moulded plaster Greek gods

and the Roman Emperors. And, unlike polite visitors

who kept their opinions to themselves, Ruskin would

have had no hesitation in telling his hosts exactly

what he thought. In fact, given the opportunity he

would deliver lengthy lectures on his architectural

views. For Ruskin, Classical architecture (and all

later architectural systems influenced by it, such

as Renaissance, Palladian and, to a degree,

Georgian) represented a corrupt pagan decadence. The

only true architecture (Ruskin went so far as to say

the only "Christian" architecture) was the Gothic,

the work of master-craftsmen who, unlike Classical

architects, were not chained to a system of

proportion and rigid orders, but were free: free to

develop ideas, styles and concepts, free to travel

across Europe and work wherever they wished. Indeed,

in The Stones of Venice Ruskin theorised that

Venice's decline from greatness coincided with her

abandonment of the Gothic in favour of corrupt

Renaissance and Classical styles. |

|

|

|

| Classical

regularity: A reconstruction of the Roman temple

of Mars together with George Gilbert Scott's Foreign

Office (1858), a Victorian public building in the in

the Classical style which Ruskin abhorred. |

|

|

|

| Christian

"freedom": The Church of San Stefano, Venice,

one of Ruskin's favourite Gothic buildings, and the

chamber of the House of Lords, designed by Barry and

Pugin in Gothic revival style in the 1830s. |

If John Ruskin made his views clear during his visit

to Badger Hall, it is not surprising that his classicist

hosts thought that he had neither talent nor knowledge!

In August 1850, after their visit to the Cheneys, the

Ruskins moved on to stay with more congenial company

(for John, at any rate; the fun-loving Effie's thoughts

are not recorded): John's friend John Pritchard at

Broseley Hall. |

| Broseley Hall was built in the mid-1700s, so it

would still, from Ruskin's point of view, not have been

an ideal place to stay. As the photograph above shows,

is is a brick-built, symmetrically-proportioned house

with its roots (as with all Georgian domestic

architecture) firmly in the Classical tradition.

However, by the end of the 18th century it had been

"improved" with the addition of a Gothic summerhouse and

a "Gothic three-seater boghouse" (not a Gothic privy,

but a rustic seat or arbour), both designed by the

probable architect of the Iron Bridge, T. F. Pritchard

(no relation). |

Broseley Hall (photo: Anne

Amison). |

|

All Saints, Broseley. (photo: Anne

Amison) |

John Ruskin would also have liked the view from the

front of the house over to All Saints Church, a very new

building at the time of his visit as it dates from 1845.

It is in the Gothic Revival style so popular in the 19th

century; specifically, it is in the Perpendicular style

which was originally used in England from the 14th to

the 16th centuries. |

John Pritchard of Broseley trained as a lawyer. On

the death of his father (also called John) in 1837 he

and his brother George became partners in the bank their

father had helped to establish: Vickers, son &

Pritchard, with offices in Bridgnorth and Broseley. At

the time of the Ruskins' visit, John Pritchard was MP

for Bridgnorth. He and John Ruskin had met through Mrs

Pritchard, whose brother, the Rev Osbourne Gordon, had

been Ruskin's tutor when he was a student at Christ

Church College, Oxford.

The two Johns were great friends: in the following year

the Ruskins and the Pritchards travelled to Switzerland

together before the Ruskins returned to Venice so that

John could finish his book.

John Pritchard must have been a far more receptive

listener to Ruskin's lectures about Gothic architecture,

since he encouraged the erection of buildings in the

Gothic style in Broseley. A local architect, Robert

Griffiths, was commissioned to build a National School

in blue brick in Tudor style in 1855, just a few years

after Ruskin's visit. A building like this exemplified

Ruskin's philosophy: its two-fold purpose was to both

introduce something aesthetically pleasing into the

daily lives of ordinary people (to give public art to

those "whose childhoods were without beauty" as Ruskin's

protégé Edward Burne Jones put it later in the 19th

century) and to improve their prospects through a better

education.

In 1861the same architect built an elaborate well in the

style known as "Venetian Gothic" popularised by Ruskin.

Broseley had a very poor water supply and by the

mid-19th century still relied on only two wells. The

well was intended as a memorial to John Pritchard's

brother George. Unfortunately (but perhaps

understandably, given its situation in the Shropshire

iron fields) the water had a very high iron content and

was undrinkable.John and Effie Ruskin paid a second,

very brief visit of only 24 hours to Badger Hall in

1851. During their second stay in Venice in the same

year Effie resumed her friendship with Edward Cheney,

who was then in the process of giving up his Venetian

apartments and packing up his collection to take it back

to England. Although Col. Cheney gave excellent advice

and assistance when some of Effie's jewellery was

stolen, he and John Ruskin were never on the best of

terms: when John was negotiating with the National

Gallery in London to purchase two paintings by the 16th

century Venetian artist Jacopo Tintoretto on their

behalf, Col. Cheney tried to discourage him on the

grounds that the paintings were church property and it

would be impossible to export them. When the National

Gallery withdrew from the sale, Ruskin placed all the

blame on the Colonel, writing many years later in his

autobiography Præterita that Edward Cheney "put a spoke

in the wheel from pure spite."

None of the three Cheney brothers married. In 1884

Badger Hall passed to a cousin. In 1953 it was

demolished, like so many country houses in the decade

after World War Two. Badger Dingle, the pretty little

wilderness, remains a much-loved local beauty-spot.

Broseley Hall still stands, although The Venetian Gothic

well was demolished in 1947. The Tudor schoolhouse is

now used as Broseley's library and health centre. It is

a very attractive building, sadly marred by the modern

desire for large and inappropriate signage. The building

has two wings, each with a large arched window: one is

decorated with the sort of additions Ruskin loved, the

heads of a medieval king and queen. |

|

|

|

| The former

schoolhouse, Broseley, with decorative details from the

window on the extreme right of the picture. (photo: Anne

Amison) |

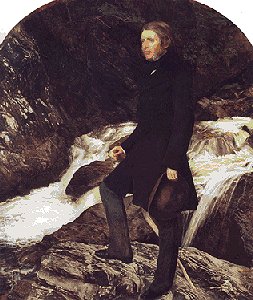

| The marriage of John and Effie Ruskin ended in 1854.

Effie later married the artist John Everett Millais.

Ironically, they fell in love when Millais was

commissioned to paint a portrait of John. Effie died in

1897. |

|

|

|

| Two portraits by

J. E. Millais: "The Order of Release", for which Effie

was the model, and his picture of Ruskin. |

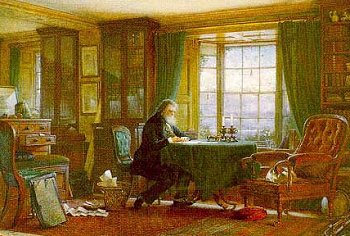

| John Ruskin became the foremost writer and critic on

art and architecture in the second half of the 19th

century. The Stones of Venice, written during his two

visits with Effie, was instrumental in the first moves

to protect and restore that loveliest, most fragile of

cities, and his name is still revered in Venice today.

He was patron of the Pre-Raphaelite group of artists;

the executor of J. M. W. Turner's will; one of the

founders of the Working Men's Colleges. He worked to

protect rural crafts and prevent industrialisation. In

old age, when he had made his home at Brantwood near

Coniston in the Lake District, he was honoured and

respected as "The Sage of Brantwood". He died in 1900,

fifty years after the Sage visited Badger.

John Ruskin in his study at

Brantwood, W. G. Collingwood, 1881.

Works

Consulted:

Jane Austen, Pride & Prejudice.

Tim Hilton, John Ruskin: The Early Years, London, Yale

University Press, 1985.

Mary Lutyens, Effie in Venice, Pallas Editions 1999.

Niklaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Shropshire.

Victoria County History of Shropshire, Volume X.

University of London, 1998.

|

Return to the

previous page |

|

|