|

One of the greatest feats of

Victorian exploration took place on 5th

September, 1862 at Stafford Road Gasworks in

Wolverhampton. It consisted of a balloon flight that

greatly increased our knowledge of the atmosphere, and

helped to lead the way to modern weather forecasting.

There were other balloon flights from Wolverhampton’s

gasworks, but this one was very different and far more

important. It was in fact a scientific experiment.

Our ability to accurately forecast

the weather depends to a large extent on our

understanding of clouds, and which types will produce

rain. The ancient Greeks understood that the heat of the

summer evaporated water, which later came down as rain.

This is known as the hydrological cycle. Isaac Newton

greatly improved our knowledge of the cycle, and

calculated how much water is evaporated into the

atmosphere.

In 1803 Luke Howard classified the

different cloud types and gave them Latin names which

were standardised throughout the world.

It’s possible that people’s intense

interest in weather, and rain in particular, was

stimulated by the severe drought in the 1850s, when

everyone was extremely worried about the shortage of

water.

One of the leading scientists of

the day, James Glaisher decided to investigate what

happened to the water vapour as it rose into the

atmosphere. The only way to get there at the time was by

balloon. In the 1860s balloons were mainly used for

entertainment, and ascents were a popular spectacle.

|

|

Wolverhampton Gasworks in the

1930s. |

In 1862 the British Association of

Science had selected Wolverhampton Gasworks as a

suitable location for a research balloon flight because

it was sufficiently far inland to prevent the balloon

from being blown out to sea, and the gasworks could

supply the gas to inflate the balloon.

Henry Coxwell was approached for

the flight, and he undertook to build a suitable balloon

at his own cost.

The balloon was 55 feet in

diameter, and 80 feet high, with a capacity of 93,000

cubic feet. |

|

Henry Coxwell was the son of a

naval officer. He saw his first balloon flight at the

age of nine, when he watched Charles Green ascend from

Rochester through a telescope.

At the age of 16 he saw Charles

Green launch a large balloon at Vauxhall.

Coxwell became a dentist, but his

interest in balloons grew. He made his first flight in

1844 at the age of 25, as a passenger in Mr, Hampton’s

balloon which ascended above White Conduit Gardens, at

Pentonville.

He began to make a series of

flights with two rival balloonists, Gale and Gypson,

many of which took place on the Continent.

By 1852 he had become one of the

country’s leading balloonists. |

Mr. Green's balloon. From the

Illustrated London News. |

|

Mr. Hampton's balloon. From the

Illustrated London News. |

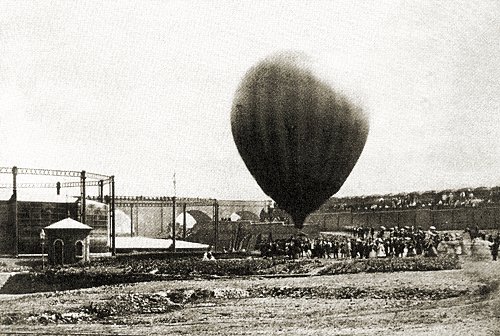

Glaisher and Coxwell made a series of balloon

flights to study the moisture content of the air.

Their third and most important flight took place on 5th

September 1862 from Stafford Road Gasworks, where there

was a plentiful supply of town gas for the balloon.

On the day Glaisher filled the balloon basket with 17

scientific instruments and they lifted off at 3 minutes

past one.

During the flight he intended to constantly monitor

the instruments to discover the quantity of moisture

that the air carried at different altitudes. |

|

The balloon rose into the cloud at

5,000 feet, and broke through it onto a plateau of

cloud. Glaisher described it as follows:

On emerging from the cloud at

seventeen minutes past one, we came into a flood of

light, with a beautiful blue sky without a cloud above

us, and a magnificent sea of cloud below, its surface

being varied with endless hills, hillocks, mountain

chains and many snow white masses rising from it. |

Lift off from the gasworks. |

Approaching the cloud.

|

The sea of cloud. From the

Illustrated London News. |

At this point Glaisher attempted,

possibly for the first time ever, to take a cloudscape

photograph. Unfortunately the attempt was unsuccessful.

During the ascent Glaisher took

regular readings of temperature and humidity as the

balloon rose ever higher, but soon things started to go

very wrong.

This was the highest manned balloon

flight that had been attempted, and so the dangers were

not fully understood. |

|

The height of two miles was reached

in 19 minutes, and the temperature was at freezing

point. More sand was discharged, and 28 minutes later

they reached an altitude of 5 miles. Up to this point

Glaisher had no problems reading the instruments but

Coxwell became breathless because of his exertions.

At one point he had to leave the

basket and climb onto the ring to untangle the valve

line, which become entangled because of the rotary

motion of the balloon.

At 29,000 feet Glaisher began to

have problems. He had difficulty seeing clearly and

could not see the column of mercury in the wet bulb

thermometer, or the hands of the watch, or the fine

divisions on any instrument. He soon lost the use of his

arms and legs and fell into unconsciousness.

Coxwell later claimed that he was

so cold and paralysed that his hands ceased to function,

and turned black from lack of oxygen. It seemed that as

the balloon rose even higher, the occupants were doomed

to die. As the air pressure reduced, the envelope would

have expanded until it finally burst, at which point the

balloon would plunge to the ground. |

|

Coxwell claimed that he managed to

grip the balloon’s rip chord in his teeth, and after

three tugs the balloon started to slowly descend. He

then let more gas out, to control the descent. It was an

extremely narrow escape from death.

As the balloon continued its

descent, Coxwell attempted to rouse Glaisher, who soon

regained consciousness and immediately continued to

monitor the instruments and make his observations.

He was a determined scientist who

would stop at nothing to get his results. He had been

unconscious for about 7 minutes.

When Coxwell told him that he had

lost the use of his hands, Glaisher poured brandy over

them. |

| Pulling the rip

chord. From the Illustrated London News. |

|

|

The whole flight took about 2½

hours. Glaisher thought that they had reached an

altitude of 37,000 feet, around 7 miles. A world record

at the time. He found that as they went higher there was

less moisture in the atmosphere. This discovery alone

enhanced out understanding of how and where clouds form,

and advanced our understanding of rain.

The descent, which was at first

very rapid, was effected without difficulty at Cold

Weston. It had been one of the greatest journeys of

Victorian exploration. A prodigious, and scientifically

significant feat. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|