The Victorian era was full of advice on industrial design and the Victorian house was full of coal scuttles. The question here considered is what influence the gurus of industrial art actually had on production, taking the specific case of containers for coal. Up until the late 18th century wood was the commonest fuel used in houses (though dry gorse and furze were frequently used in commercial premises such as bakers and brewers and was probably used by the poor in places where it was abundant and wood was not; and peat or turf was used in places where it was available, such as Ireland, which was infested with turf as it was free of snakes). Logs could be stacked anywhere but it was not uncommon for it to be stacked in the fireplace. In better class houses there might have been log baskets, made of willow or in a wood stave construction, with metal bands, often of brass. In the biggest houses the question of how to store fuel in the families rooms did not arise as the servants would bring in fresh logs as need be.

By the late 18th century wood was in desperately short supply and coal was increasingly used as a fuel in all classes of houses. Fireplaces had to be re-designed for the purpose and some provision had to be made for coal. It was soon established that coal was stored in the cellar or, in smaller houses, in a half-cellar or a large bin sited in the back yard. But where did you store the coal for immediate use in making up the fire as it burnt down? It seems that while some had found that a few logs in the fireplace were quite acceptable, nobody wanted a heap of coal in the drawing room. One approach to the problem was to refuse to have coal in the drawing room at all. Judith Flanders in "The Victorian House" quotes from Mrs. James Ellen Panton, who published at least five books on home management from 1888 to 1896. Ms. Falndesr writes: "coal scuttles were not approved by all. Mrs. Panton thought they should not be permitted; it was no trouble she airily assured her readers, to have coals brought in whenever the fire needed more fuel". But the matter might go far further than that. " Mrs. Panton … instructed that an invalid’s bed was to have a screen nearby so that the room could be cleaned without her seeing it "and so save the invalid from the nervous strain caused by the worry of watching the movements of the servant" although even then "the noise of the coals and the moving of the fire irons are maddening if improperly managed". Her solution was that each lump of coal was to be wrapped separately in a piece of paper before the coals were brought it, so they could be placed noiselessly on the fire". The servants, who were assumed to be available at all hours of the day and night to lug in more coal and make up the fire, probably carried the coal in a simple bucket, though in later times they were assisted by sheet metal coalboxes on wheels (at least one of which was made in Wolverhampton by Henry Loveridge) which could be dragged around to wherever needed. (But the noise such contraptions must have made would have been intolerable to Mrs. Panton).

But if the coal (and the attendant fire irons) were to be in the drawing room, then chucking it into a simple bucket would hardly do. The drawing room was seen as the heart of the house and the fireplace was the heart of the drawing room. Further the house was not merely a thing of bricks and mortar, providing shelter and a place to eat and sleep but much more.

The whole house had to be kept attractive (by the wife or the wife supervising the indoor staff) so that the husband did not swan off after his evening meal to the pub, the club or worse. And it went further than merely holding the family together. The house was not only a reflection of the morality of those who resided in it but it could be a positive influence on those morals. And further still, if the house were tastefully and beautifully decorated and full of beautiful objects, that would improve the taste of the occupants and elevate their higher feelings and sensitivities. Everyone said so, from the art establishment in the form of Cole and his group (including George Wallis) to Ruskin and way out to Christopher Dresser who wrote that: "Art can lend an apartment not only beauty, but such refinement as will cause it to have an elevating influence on those who dwell it".And, of course, Mrs. Panton had something to say on the subject: she was "quite certain that when people care for their homes, they are much better in every way, mentally and morally, than those who only regard them as places to eat and sleep in … while if a house is made beautiful, those who are to dwell in it will … cultivate home virtues".

Whatever disagreements there were about what was beautiful and what was not, nobody thought a tin bucket full of coal was a thing of beauty and fit to elevate the morals of those who contemplated it. There was, therefore a demand for something in which to store the coal in the drawing room, the dining room, the bedrooms and other public rooms. And, whatever it was, it ought to be elevatingly beautiful. The manufacturers of Wolverhampton had to meet this challenge if they were to make sales. The relevant manufacturers were those who worked in sheet metal, whether tinplate, sheet steel, brass or copper; and those who worked in cast iron – though this material, though practical, seems to have gone out of favour, probably on account of the weight, not to mention cost. Wolverhampton seems to have had no notable workers in wood – furniture makers - until Stroud’s Niphon works went into the large scale production of furniture sometime near the very end of the 19th century. But whoever worked in wood and tried to make coal containers out of wood, needed fittings for them and the Wolverhampton brass workers, both sheet workers and foundries, were well up to supplying their needs in the way of scuttle furniture.

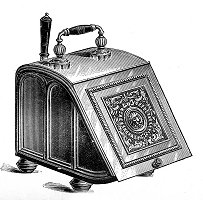

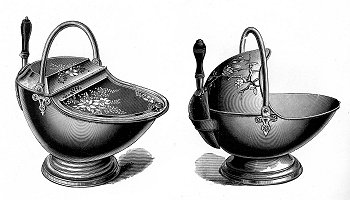

But how were they to be designed? The Georgians had left some precedent, though it is difficult to identify specimens. Surviving examples seem to be a simple tub shape (which it could not have been easy to get the coal out of) and a tub on its side (which would have been easier to get the coal out). But note that in these examples the nasty black coal remained visible. By the end of the century it had turned out that most coal scuttles had a lid of some sort to hide the horrible coal – but by no means all. Many people must have found the sight of coal acceptable (possibly influenced by the fact that lidless scuttles would be cheaper). Our Victorian manufacturers were not short of advice on how things should be designed. A plethora of writers produced a plethora of books – and there was, perhaps surprisingly, a large degree of agreement amongst them at least on the basics: that form follows function, that there should be truth to materials, and that almost any visible flat surface should be decorated. (Many of the books about design assumed the first two points and spent most of their time dealing with the decoration of surfaces, leading to the misleading impression that the Victorians cared little or nothing for function or truth to materials). The design gurus were also quite sure (and became very noisy about it after 1851) that most design, especially of goods for use within the house, was bad. They allocated the blame for this state of affairs to the ultimate purchasers who had no taste; and to the manufacturers, who were as bad. But many of them found that the chief culprits were the middlemen – the shopkeepers - who claimed to stock only what they thought would sell and who thought that the only things that would sell were the appalling designs they themselves, in their tasteless ignorance, favoured. The ultimate purchasers could only buy what the retailers offered; and the manufacturers would only make what the retailers would buy. It all lead back to the retailers’ and their bad taste. The design gurus were much concerned about where to break into this vicious circle but, in effect, ended up with a attack on all fronts. So what were Wolverhampton’s manufacturers to do? Some, of course, would ignore the art gurus and produce whatever their retailers would accept. Others, like Loveridge and Perrys, were interested in design and tried to produce items which the design gurus favoured. Perry did this by commissioning designs from Christopher Dresser (and it may be that Marston did likewise). Loveridge approached the problem by being the leading light in setting up the Wolverhampton School of Art, and sending his staff there. He probably also designed many of his goods himself - his firm always claimed to be designers as well as manufacturers. But, certainly in the case of Perrys, and almost certainly in other cases, such as Henry Fearncombe, the manufacturers produced items of high design and items of popular design. But we can also find more specific instances of Wolverhampton people trying to produce articles which served their purpose and adorned the living room. The earliest example comes from the Great Exhibition of 1851, In the Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the Industry of All Nations, published by Virtues for the Art Journal, in 1851, we find these three coal containers and some notes on their design:

"The three coal-vases, or, as such articles of domestic use are generally called, coal-scuttles, are from the establishment of Mr. Perry, of Wolverhampton, who has, with much good taste, endeavoured to give a character of elegance to these ordinary but necessary appendages to our "household hearths". Hitherto, in whatever room of a dwelling-house one happens to enter the coal-scuttle is invariably thrust into some obscure corner, as unworthy of filling a place among the furniture of the apartment, and this not because it is seldom in requisition, but on account of its unsightliness. Mr. Perry's artistic-looking designs, though manufactured only in japanned iron, may, however, have the effect of drawing them from their obscurity, and assigning them an honourable post, even in the drawing-room. It is upon such comparatively trivial matters that art has the power to confer dignity; and notwithstanding the absurdity - as we have sometimes heard it remarked - of adopting Greek and Roman models in things of little importance, they acquire value from the very circumstance of such pure models having been followed. And further on we come across four engravings which "represent coal-boxes, to use the only term that seems applicable to their purpose, although it is inappropriate when the form of these objects is regarded; they are manufactured in japanned iron by Mr. H. Fearncombe, of Wolverhampton".

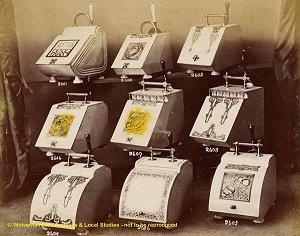

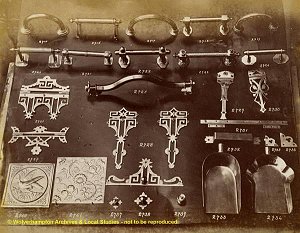

One can understand why the designers of these things might have taken both vases and tureens as suitable design sources – but why anyone thought that an enormous clam shell would sit appropriately in the hearth is more mysterious. It may be connected with the enthusiasm Victorian art gurus had for designs based on nature, though in this case carried to a rather literal extreme. Note that the writer of these critiques (who may well have been Cole and/or Wallis) has a problem knowing what to call these objects: coal boxes, coal scuttles, coal vases. But that was not the last of it. Our manufacturers seem to have been well aware that the right name was half the selling battle. In the Loveridge catalogue of 1897 they also use coal chest, coal scoop, coal hod, coal Canterbury and, even, purdonian (sic. The more usual spelling these days seems to be purdonium, which Collins English Dictionary says is "a type of coal scuttle. Having a slanted cover that is raised to open it and an inner removable metal container for the coal. (C.19: named after its inventor, a Mr. Purdon)." The basic word seems to be "scuttle", from the old English scutel, a dish or platter. But the earliest use of coal-scuttle found by the OED is 1849. By the time of the 1869 Industrial and Fine Arts Exhibition held in Wolverhampton, coal scuttles of designs fit for the drawing room were widely available. The collection of photos of the exhibition (held in the City Archives, and probably by Haseler) shows some general views, inside and out, and other views of exhibits, probably chosen simply by which manufacturers were willing to pay Haseler to take them. They include four photos of displays of coal scuttles.

These are most likely to be by Richard Perry Son & Co and by Henry Loveridge and possibly two others. In George Wallis’ Special Report on the Local Manufactures there is no specific mention of these scuttles; one can only assume that either they were seen as sufficiently covered by his general remarks on these manufacturers or they were not fit to comment on.

In the 1878 Exhibition (which seems to have been a different sort of exhibition, with no fine art section, all the goods for sale, and an emphasis on "gas cooking ranges, stoves, heating and other gas apparatus" and "machinery") coal scuttles do not seem to get much of a look in but there are coal vases in wood by a Birmingham furniture maker. At the 1884 Exhibition (which had reverted to type as a Fine Arts and Industrial Exhibition) the catalogue seems not to mention coal scuttles specifically but there are many entries with general titles which could well cover such objects. In his book on the japanning and enamelling trades of Wolverhampton, William H. Jones makes large claims for the company Jones Brothers, of which he was a leading member, as innovators in production and design. He may have been making the most of what innovations they made. He claims that, from its earliest days, the "firm introduced many novelties and did much to improve their manufacture". In particular, sometime shortly after 1862, "Jones Brothers & Co brought out an entirely new-shaped coal vase. Previous to this, a useful but ugly article of furniture called a coal-scuttle, with an open mouth filled with lumps of coal, was kept in the back kitchen. The new-shaped vase now introduced had a neat and pleasing appearance, being somewhat in the shape of a nautilus shell. The coal was entirely hidden under a highly ornamental cover. … The new-shaped vase was improved by being fitted with handsome brass handles, which had opal mountings. … To make it more attractive glass panels were inserted in the covers and these panels were ornamented with pictures and photographs, taken from pictures such as the "Monarch of the Glen" and "Dignity and Impudence" by Landseer …. Others were fitted with splendidly decorated panels, embossed with gold and colours, and new and brilliant designs composed of paste jewel stars on black grounds. … These glass panels gave an opportunity for the japanner to display his artistic taste …".

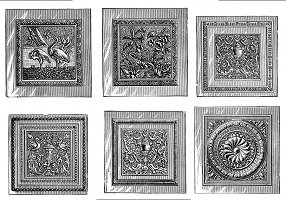

So Wolverhampton manufacturers were certainly producing coal boxes in many materials and decorated in many ways. Were they at the forefront of design? Did they respond to the demands made by the art gurus for better design? Certainly George Wallis consistently praised Loveridge’s work and Richard Perry’s work and noted a general improvement in design during the later half of the century. But the information we have on coal scuttles rather suggests that many of our makers used a shot gun approach – they offered as many designs as possible in the hope that one or more of them would appeal to all possible markets. Loveridge’s catalogue of about 1897 shows 89 different designs of coal boxes and many of these could be fitted with any of the 12 different designs of repousse brass panels, giving an enormous number of possibilities. The catalogue also announces that "New shapes and patterns of coal boxes are produced every season to suit the prevailing tastes and styles of ornament, and will be shown by our travellers or patterns will sent on application". This rather suggests that the practical manufacturer was more influenced by passing fashion than by the principles of good design that the art gurus propounded; but that, if you could produce enough designs, some of them, surely, could be sent to the great national and international exhibitions and get the approval of the critics. But some of them, at least, produced leading edge (or, anyway, way out) designs as an addition to their range. Perry’s and Loveridge’s and Marston certainly did this – though not, so far as we know, in the case of coal scuttles. Examples from the Loveridge catalogue are shown below:

Of course the shotgun approach ensures that some designs will be panned by the critics. Mrs Orrinsmith , in her "The Drawing Room and its Decoration and Furniture", condemned a pretty wide range of such products: "coal scuttles ornamented with highly-coloured views of, say, Warwick Castle … [or] screens graced by a representation of Melrose Abbey by Moonlight with a mother-o’-pearl moon". It was probably not only Jones Bros. that she was getting at.

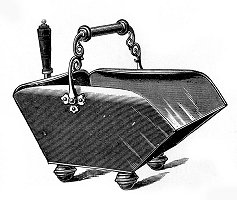

"As a primary matter Mr. Pattison discourses on what he chooses to call, the modern coal scuttle, which as happens is not a coal scuttle at all, but simply a coal box. A coal scuttle has three distinct uses as such; it acts as a shovel to get the coals out of the coal heap, it holds the coals for use, and is used as a shovel to put the coals on the fire. This is the use and the original intention or design of the coal scuttle, and it happens that the brass or copper object of his admiration is, or was, simply a parlour "sham," since it never went down to the coal heap to be used according to the purpose of its form and construction, but was kept bright and clean for show in its "best room" condition, and was simply used as a coal box, so filled with fuel that it was necessary to supplement its original shovelling qualifications with another shovel to put the coals on the fire, or use the tongs. "The original coal scuttle was a very primitive affair, and was formed of a single sheet of iron cut to shape and then bent and riveted together, and specimens may still be seen on the coal-pit banks of Staffordshire. It was a large shovel with a high back and sides, a handle across the top in the manner of a bucket, and another on the outside at the back. "Now I am not concerned to defend either the design, construction, or decoration of the japanned iron coal box, which so excites the esthetic ire of Mr. Pattison, but I am concerned that the true principles of constructive design, even in a coal scuttle, should be understood; and I think any one who objects to the black lac varnish to defend the metal of the coal box from rust and give it a smooth and clean surface, and at the same time can admire Japanese lacquered wood and paper, simply "strains at a gnat and swallows a camel." Some may think that what Wallis insists was a scuttle was really a hod. But that is of no great consequence. "As one of those preachers and teachers, not of thirty but of forty years ago" he insisted that design had improved in that time and that public taste had improved in that time.

At a slightly later period – the turn of the century but very much, culturally, in the Victorian era – we may also consider Sankey’s of Bilston whose "Art Metal Ware" catalogue of 1910 includes two pages of "Artistic Designs in Coal Boxes" showing 25 coal boxes. Some of these are in steel and wrought iron and can be described as traditional in design; but most of them have emphatically art nouveau designs, very much appealing to the then current design fads.

Early on we know that some of the local makers designed their coal scuttles as vases, tureens and shells. But nevertheless, when in situ, they could not have been anything but coal scuttles.

One of the design influences on many late Victorian coal scuttles was the Arts and Crafts movement. Arts and Crafts makers had their own works to offer for sale - but, of course, hand made, one at a time.

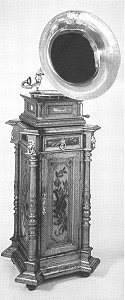

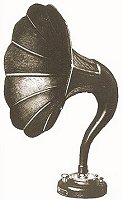

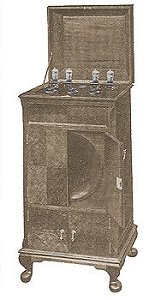

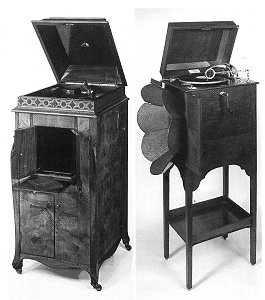

A principle of the Arts and Crafts movement was that the hand of the craftsman should be apparent on the object made. This means, inter alia, that if there is a straight line in your design, you made it slightly erratic and wobbly, because a factory could, and invariably did, make it straight. So you, in effect, did the job badly to prove that you had made it yourself - and then you had to charge a lot more for it. Doing the job badly might have claimed one advantage when working with bright surfaces and that is that irregularities catch the light and add brightness and sparkle. A comparison of hand tooled gold leaf on book bindings with gold tooling printed by a block, will make the point. But since impressions on metalware soon fill with detritus, the effect is lost. When metal is beaten flat by hand it takes up the mark of the hammer and, if not skillfully completed, those hammer marks remain visible. The metalworker prided himself on being able to beat metal completely flat - and Joseph Sankey exhibited at national exhibitions two japanned trays, each about four feet across, which were perfectly flat. But rolling mills could roll sheet metal perfectly flat and do so quickly and cheaply. So perfect flatness looked like factory work. So the Arts and Crafts people beat their sheets by hand and left the hammer marks on, so that you could see it was hand made. So the factories took their nice flat sheets and embossed them with a pattern which looked like hammer marks. It is interesting to compare the design of coal scuttles, which mostly ended up looking like coal scuttles. with the response, at the beginning of the 20th century, to two other newcomers to the drawing room, the gramophone and the radio. The first widely produced models of these had great horns sticking out of them and the radios had their valves and other bits proudly on display. They must have looked very odd in the drawing room.

This was not to last for long. AJS of Wolverhampton, who were leading makers of these items, like other makers, soon found ways of making the horn look as if it was made of wood; and then ways of tucking the horn away altogether; and then ways of hiding all the works, even the knobs, in what could pass as ordinary furniture.

These attempts at disguise continued but, in short course, probably because people were getting used to these things, and probably for reasons as much to do with cost as appearance, most radios were not disguised at all. In later times TV sets followed the same course. It may be that our tendency to have a good laugh at Victorian design is not fully justified. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||