|

How I

Learned the Nuts and Bolts of a Good Day’s Work.

Memories of an

Apprentice Anthony R. Andrew

After receiving my exam results in

1962 and leaving Short Heath Secondary Modern, I decided

I would like to be a draughtsman, the reason being that

I had achieved a distinction in that subject. I went on

a job search during August to many local factories but

failed to get a job. I was beginning to get

disillusioned and fed up with being rejected when my

mother suggested I enrol for a college course, which in

her words meant that "I wouldn't end up in a factory".

I enrolled for a full time

pre-engineering course (electrical bias) and spent an

enjoyable time learning new subjects and doing practical

electrical tasks. I passed the course in August 1963 and

left Walsall and Staffs Technical College to find a job

but "not in a factory". After writing off for many jobs

to complement my new knowledge and school exam results,

I failed to achieve employment as a draughtsman so the

only route left was to try for an apprenticeship in

engineering. My quest for apprenticeship status began at

John Harpers, Willenhall, then Wilkins & Mitchell,

Rubery Owen, and Easiclean, but to no avail. Finally I

was sent from the youth employment service to Charles

Richards Nuts & Bolts Ltd. |

|

Charles Richards' Imperial Works

in Heath Road, Darlaston in the 1930s. |

|

Massive

After my interview at Charles

Richards I was offered an engineering apprenticeship. My

father was asked to attend the second interview to sign

my indenture documents. After the formalities were

completed I was welcomed to Charles Richards Nuts &

Bolts Ltd for the next five years. It was very strange,

that first day at Richards's. The first feeling on

entering the small wooden door off Heath Road was

"Bloody hell, what have I signed up for?" (and wishing,

in the back of my mind that I had worked harder for my

Eleven Plus). We were in the Black Forging Department,

with all sorts of massive, noisy, hot machines, banging

and forming red hot steel metal bars into nut and bolt

shapes.

We (the apprentices) nervously

followed the chief instructor past workers who were

feeding furnaces, loading power presses with steel

billets, pushing trucks, pulling trucks and feeding

automatic forging machines with long, round bars. The

workers stared at our keen young fresh faces with a look

that said "Why do you want to work in a place like

this?" The main things you noticed upon this first

"tour" were the noise, dirty floors, old doors and steel

windows with glass that was filthy dirty, due to the

smoke, heat and sweat of decades of hot metal

manufacturing through two world wars and numerous

recessions. There was also that "factory metal smell"

that was always synonymous with any steel bashing

establishment of that era.

We arrived at our destination,

which was the apprentice training school situated within

the "bowels" of the fitting and machine shops. The

department was perched over a canal basin, which was to

become very useful during the first year of training.

After the formalities of health and safety instructions,

time planning sheets and general works information, we

were asked to introduce ourselves to each of the other

ten apprentices who we would be working with for the

next five years - all strange faces but friendly enough,

some serious, some nervous, some funny and although some

were tall and some were small, we all looked the same in

our new baggy boiler suits. |

|

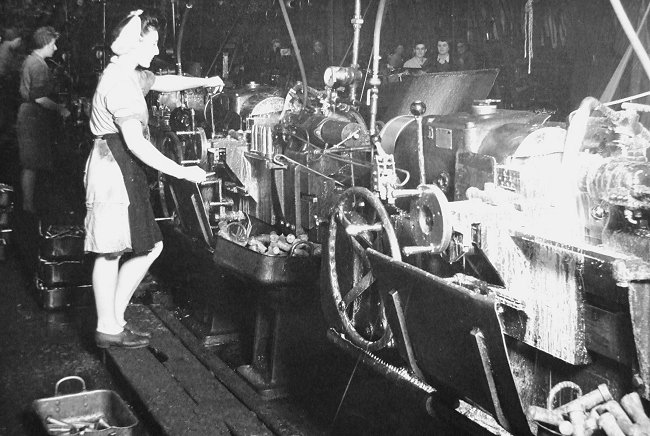

Part of the bolt production line. |

|

After a few weeks induction we

began our training schedule beginning with machining of

components to engineering drawings in the training

school. This was when we realised the canal basin

outside the window was to prove very useful.

If a particular part was scrapped,

usually due to chatting to your mates and leaving

autofeeds on, it could be ejected through the window

into the cut when the instructor was out of the

department. The main thing was to chuck it as far as

possible to avoid a big pile of rusting metal parts

which was up to the canal surface, this being left by

decades of apprentices throwing their scrap in the cut.

The first year was OK, although we

had to attend college for one day a week, which was a

bit of a shock. But unlike school, we began to be

treated like adults. Once we got used to going to

college it was great - a day off work. It was this year

I got my first scooter (a Vespa) which gave me freedom

to zoom around the locality with my new apprentice

mates, going to coffee bars and the pictures.

Mending

After the first year of training

and college tuition it was time for us to be allocated

to various departments in the company. My first move was

to the maintenance area in the New Imperial Department.

This was my first chance to obtain new skills of machine

repair and servicing to achieve continuity of nut and

bolt production.

This area was "over the road" and

seemed a million miles away from the training school. I

felt like I was a proper worker, assisting the fitters

and mending machines. The people who worked on the shop

floor were the salt of the earth and the maintenance

fitters soon accepted me as the new boy and became my

mates. |

|

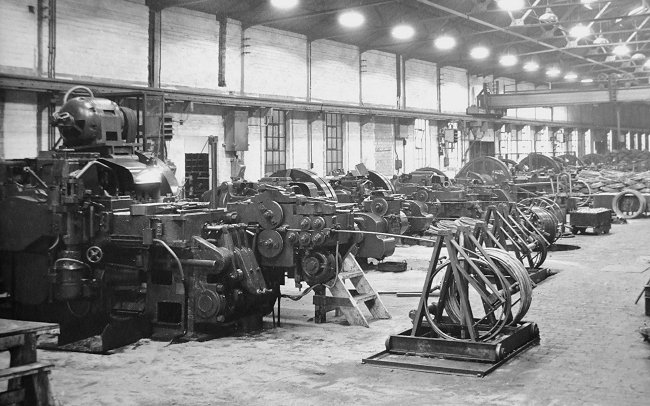

Another part of the bolt

production line. |

|

Many things happened during my six

months in this area. Once, when I was on a lunch break,

I decided to toast my sandwiches on a small electric

fire with a home-made wire fork. The work that morning

had been particularly arduous and while doing my

toasting I fell asleep and my fork touched the open

element waking me up with an electric shock up my arm. I

tried to let go but at first couldn't. After a lot of

yelling and shaking I finally broke loose, ran outside

and dived in a pile of snow, which being January had

fallen the night before. After lying there for five

minutes or so I looked upstairs to big "G" and said

thanks. Fortunately it was only 240 volts and not 415

volts. The rest of my time in this area was enjoyable

and completed with no more "shocking" moments.

The next move was back to the

fitting shop where I would be working with the machine

tool fitters for six months, stripping down and

rebuilding various machines used in nut and bolt

production. I immediately enjoyed it in this department

and felt at home with the tasks I was asked to do. The

machine tool fitters were great blokes who were mostly

friendly and helpful to the "new apprentice". There was

Fred Hampton, Jack Williams, Charlie Bailey, Jimmy

Rogers, Bill Griffiths and Arthur Bettley. Some of these

were workers who had helped keep the company production

going through the war and since then I have often

wondered if their efforts and that of other similar

workers were appreciated by the government of the day,

which contributed to the defeat of Hitler through their

hard work.

Having begun my six months working

in the fitting shop I found out some of my fellow

apprentices were in there as well, which was great and

meant we could have a few laughs during the following

months, which we did. The first thing you were told by

the foreman was to listen to what you were told by the

fitters and learn from them. I was assigned to work

mainly with Fred Hampton who, I had been told, was one

of the best engineers in the shop. Fred was very

instructive and taught me all the skills he could in six

months. |

|

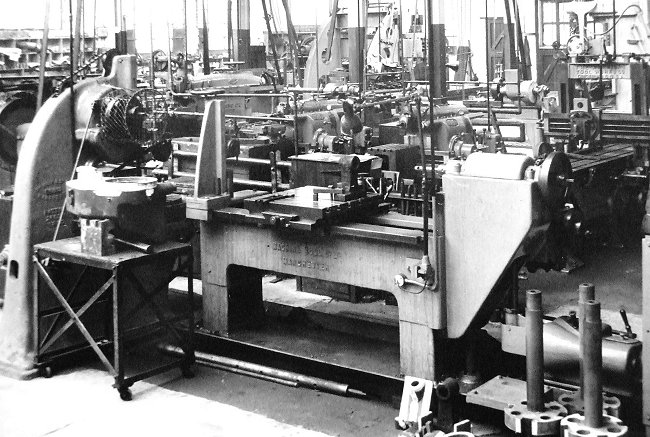

Large diameter coils of steel are

threaded into machines, possibly to be cut and threaded

for studs. |

|

I moved on from the fitting shop

for six months in the laboratory. This was the

department that tested the quality of the products that

were "heat treated" for greater tensile strength and

quality. The lab was hidden away up an alleyway by some

toilets and upon first entering, it was reminiscent of

the science room at school. The main machine was for

tensile testing of bolt samples taken from the heat

treatment process, which were then turned down on a

lathe to a defined cross sectional diameter before being

fixed in the machine tooling and pulled under hydraulic

pressure until it fractured. The result was then

recorded and logged before testing the next sample.

At first this was very new and in

those days "hi tech", but after a few hours of "bosting"

bolts it became extremely boring. After my six months

confinement in this place I was finally transferred back

to reality into the Bright Shop maintenance area. Great!

A chance to get my hands dirty and have a laugh with

some of my mates. The fitters in the shop were down to

earth and hard working. The chargehand was George Lees

and the fitter was Bill Foulkes. In this department you

were taught to think for yourself and get on with the

jobs.

Overtime

Any problems were soon rectified by

Bill or George, who were always willing to help and

teach you all the tricks of the trade. Day-to-day

maintenance was supplemented by Saturday morning

overtime, which came in very useful for a chap who now

had an A35 van to support. I was then moved back to the

fitting shop to do six months of machining. Having spent

the majority of my time in this area I was immediately

at home with my surroundings and began, after initial

instruction, to work on the planning machine. |

|

The corner of a machine shop,

possibly in the maintenance department. |

|

The time had come for my next

training period, this time in the Drawing Office, the

move I was looking forward to, although I was a bit

nervous of the works engineer.

The next Monday I started at 8.30

instead of 7.30, wearing my best suit and shiny shoes

and reported to the chief draughtsman, Les Foulkes. He

was another nice bloke who had worked his way up from

the shop floor. I was introduced to the manager, works

engineer, and the girl who was the drawing tracer and

another girl who was the junior tracer. The change from

shop floor to an office environment was amazing. You

were treated like a person, not just another worker, and

I felt quite at home.

My first task was to learn how to

print off large drawings on the ammonia print machine,

then to trim them on the guillotine. This was OK, but

sometimes you did get a lungful of ammonia which

certainly cleared your sinuses.

The following months passed with

great memories. The office was a happy place, with Les

having his daily apple, always peeling it then slicing

it to eat, followed by a cigarette. This was usually

smoked in conjunction with the junior tracer, who also

smoked and used to launch a fag over the drawing boards

to reach Les at the back. This was repeated in reverse

at tea break. Being in the drawing office was another

world from the factory floor and if I had to go out to

take some measurements for a drawing my mates would say

"yow'm dressed up a bit posh, ain't ya". I would reply

that they would have to "dress up" as well when they

went into the Drawing Office.

While I was there we had loads of

good times. I hoped that I could stop in there and when

an interesting task came up I thought I might be asked

to stay on permanently.

This was the time in the mid-1960s

when nuts & bolts companies were changing their logos to

refer to "fasteners" instead of the old fashioned "nuts

& bolts". My directive from the works engineer was to

modify all existing signs and wall letterings. The next

few weeks I spent climbing ladders, painting out "nuts &

bolts" and painting in "fasteners". I also had to draw

all the walls to scale, showing every brick and every

letter change for contractors to do the external

lettering modifications. The engineer was satisfied with

my efforts and I was hoping he would offer me a job in

office, but sadly the offer never came.

It was a turning point in my career

and I knew my ambition to be a draughtsman would never

be fulfilled, at least not at Charles Richards. Maybe it

was that secondary modern stigma again. I'll never know.

The powers that be then transferred me to the General

Toolroom for three months, which was noisy and full of

comedians and jokers, all great working people. The work

was interesting but not really what I wanted so after

three happy months I went back to the fitting shop to

finish my apprenticeship. |

|

Part of the packing department. |

|

Working in the fitting shop was my

last placement before completing my training and I was

assigned to the machine tool bench, being given the vice

and bench area formerly used by Jack Williams, a top

class engineer who had recently retired. I had a lot to

live up to, but luckily it was next to my "mentor" Fred

Hampton, who was approaching retirement in the next few

years. Although I was still an apprentice I was given a

"proper job", machine rebuilding, the first one being a

"5/8" Van Thiel hot nut forging machine, which usually

took four to six months to complete.

Fred taught me the correct

procedures to begin a machine refurbishment. It began

with a general stripping down of parts from the main

machine body, each part having to be cleaned with

paraffin and rags, ready for inspection for wear and

replacement of bearings, fastenings, oil pipes etc. The

main body was then cleaned down.

Keepsake

There was a great feeling of

satisfaction six months later when the machine was

finished and ready for production. The best thing was

being presented with the first nuts produced on the

machine for a keepsake. As soon as one Van Thiel machine

went out another one was taken off production and

brought in to the shop for rebuild. This time I knew

what to do and got on with it. I was nearly a machine

tool fitter.

Life in the shop wasn't all work

and no play, we had many distractions from the daily

grind, especially at lunchtimes. In winter we had the

darts school in the welding shop, when we would all

become "Eric Bristows" for half an hour, throwing our

bespoke factory darts in a sort of in-house league. In

the summer we used to have a "kick about" in the loading

bay after going up "Darlo" to get some "orange" chips

from Middleton's chip shop. Most of us now had cars and

a new lunchtime venue was on the car parks where we

would suddenly become expert mobile mechanics.

Christmas festive celebrations were

always one big booze-up with the last day spent cleaning

up and generally housekeeping in the fitting shop with

an air of expectancy that we would be told we could all

finish at lunchtime, which always happened. When the

hooter went off there would be a stampede of apprentices

through the door to see who would be the first in the

pub, usually the Why Not pub. After the first hour or so

some of us would go "on tour" to a few more of the local

pubs, The Bush and The Glamour House. |

|

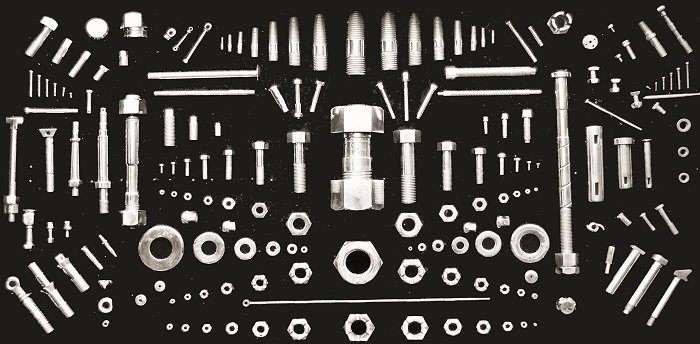

A few of the firm's many products. |

|

In August, 1968, the end of my

apprenticeship had arrived and one afternoon I was

called into the boardroom and presented with my

indentures by the managing director in the presence of

my training manager and supervisor. After a short speech

and a handshake I received them - not much of a ceremony

after all the grafting I had done in five long years.

I stayed on, having been "half

promised" promotion in a few years, but on reflection I

think it was a mistake to stay on because all I used to

hear was "you won't get promotion, because you are too

useful on the bench rebuilding machines", and they were

right. So after a further seven years as a machine tool

fitter, and becoming "part of the furniture" at Charles

Richards's, I decided to leave and get another job in

1975.

I feel privileged to have known the

people who were my workmates and friends in the 1960s

and early 1970s and who were hard working, dedicated

Black Country folk. My time as an apprentice taught me

to respect people and to do a "good day's work for a

good day's pay". |

|

The remains of Imperial Works in

2008. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|