|

We are always hearing that times

were tough in the old days. Well, they clearly were – as

the words of Alice Hall of Darlaston testify. She was

born in 1904 and her stories of real hardship - and of a

childhood without the care of a mother - bring to life a

bygone era.

Official documents tell us the key

dates in the lives of our forebears. As such

certificates of births, deaths and marriages are vital

to all historians - and the information they give us can

be strengthened by census entries. And yet, important as

such evidence is, it lacks much. It can give us pointers

towards the lives led by our people, but it cannot pass

on their thoughts and emotions, their trials and

tribulations, their hopes and achievements - the very

warp and weft of their being. For such we need to hear

them, either through their memoirs or their recordings.

One of those fortunate to have the

words of someone from the past is Pauline Poole. The

words are those of her mother, who died in 1994. Pauline

wrote them down because "I was listening to her opinions

one day, which was in 1989, of life at that time, when

she began to compare then with how it was in her early

life and I decided to make a note of what she was

saying. I was a secretary and could still capture her

words very easily in shorthand. I came across my

original typed copy, which was done on a small portable

typewriter, when I was looking for something else the

other day and having re-read it. It struck me that maybe

you would find it interesting to read too."

Pauline stresses that she is "very

interested in anyone's personal stories but more so the

further back we go, and she believes that it is vital to

keep the past alive for the generations to come.

|

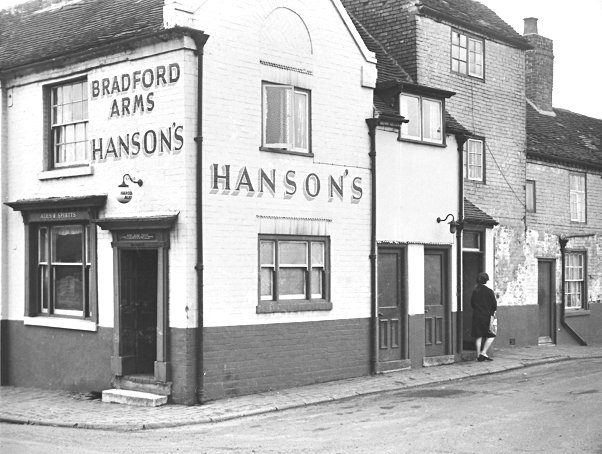

The Bradford Arms, known as 'The

Frying Pan' stood on the corner of Bilston Street and

Eldon Street. From the

collection of the late Howard Madeley. |

|

Misfortunes

She says: "To me now, my own

childhood and early life is like looking back to a black

and white film and I feel that socially, life is moving

on a pace never known before. After all, when we wake up

each morning, the previous day is our personal history."

Alice Hall, as she was born, knew

real hardship. Her memories bring to the fore the harsh

effects of personal loss and the misfortunes of a

childhood without the care of a mother who died too

young. Alice grew up in a hard era, one in which the

poor only got by with the help of kith and kin. When

that extended family was missing then the travails of a

youngster could be heart wrenching. Yet for all the

adversities she faced, Alice was never embittered.

Here then are the moving words of

Alice Hall, the beloved mother of Pauline Poole. Through

her words she lives on:

“Quite often, when I hear someone

complaining that the state benefits they are getting aren't enough to live on, it makes

me think back to my own young life and reflect on how

very different things were then. I was born on August

8th, 1904, in No. 2 Court, Bilston Street, Darlaston,

very close to the house where John Wesley stayed and

which it was said, he used as a Meeting House.

My family later moved to No. 4,

Eldon Street. My brother, sister and I and a tiny baby

were left without a mother in 1907, when I was three

years old. I clearly remember my mother being ill in bed

downstairs and one day hearing my brother cry out in

pain in the street. There was a pub on the corner at the

top of the street called the 'Bradford Arms' (nicknamed

'The Fryin' Pon') and like most pubs at that time, they

made soup which people would fetch in a jug for a few

pence.

My brother had been running up the

street with a friend named Shaler (surname) and he

bumped into a lady coming out of the pub with a jug of

steaming leek soup in her hands. The leeks stuck to his

neck and he carried the scar for the rest of his life.

Mother struggled out of bed and I can see her now,

standing on the doorstep with long black wavy hair,

shouting, 'Oh! My lad!' Shortly afterwards, back in bed,

I remember her words, 'Let me back' - and she died.

Rose's Bull was blowing 9am at the time. This was a

factory in nearby Stafford Road.

|

|

Eldon Street in the 1960s when

most of the buildings in the area had been demolished.

From the collection of the late Howard Madeley. |

|

Funeral

For the funeral I wore a little

black dress with puffed sleeves and white cuffs and

collar and I remember it was a horse-drawn hearse. The

horses had black plumes and the men wore black high hats

and black tail-style jackets. The funeral firm was S.

Webb & Son of Wednesbury. An aunt came to help for a

while and she lay on the baby, who shared the same bed,

and the child was suffocated.

From then on, the family was split

up. My brother, Ted, was fostered with a family in

Slater Street, Darlaston. He was about seven at the

time. His friend's family, the Shalers, had a shop in

Cross Street, at the bottom of Eldon Street. Our sister

Irene, who was only a toddler, was looked after by

relatives in Dudley, where our mother's family came from

and we lost touch with her until I was fourteen and

needed my birth certificate when it was time to leave

school and get a job.

My brother, Ted, was kicked on the

shin about this time and it was ulcerated. He was looked

after by Dr. Fox at the Workhouse, 100 Pleck Road,

Walsall, now a part of the Manor Hospital. I was in the

Workhouse for a time. I had been offered to several

people to live with them and I was turned away. In the

Workhouse, I can remember a man with a disfigured mouth

through cancer.

We used to be given cod liver oil,

with an arrowroot biscuit to take the taste away. I

slept in a tall cot. My brother used to do jobs for Dr.

Fox when he was growing up which included going with him

to take care of the horse and governess's cart, while

Dr. Fox was at the Workhouse.

I used to go to the Old Church

School in School Street, Darlaston for a short time and

I can remember walking in file to St Lawrence's Rectory

garden for a party on the occasion of Queen Mary and

King George V's Coronation. The Rectory garden's big

entrance gates faced onto Church Street (opposite what

is now a chemist). The garden gates have only recently

been removed and the entrance bricked up in the wall,

but the brick gate posts are still there, on either

side. (This was early in 1989.) We were given a small

metal box of chocolates with the King 'and Queen's heads

on the lid. I shared a desk with Percy Hickman, whose

family shop was a grocer's, where the Darlaston Carpet

shop is now, by the 'White Lion' pub in The Fode.

Then a family called Owen

eventually took me in for a weekly payment of 3/- (three

shillings) from my Dad.

|

|

The Barley Mow pub in Cross Street,

awaiting demolition. From the collection of the late Howard

Madeley. |

|

Married

They lived at No. 4 Bush Street,

The Green, Darlaston. I had been passed from pillar to post, unwanted by

one or another but I was to stay here until I married in

1932. When the Old Church School was closed in 1980,

they had an open week for all the old pupils to look up

their own old school records, and the comment written in

the margin at the side of mine was 'Left the District'.

I had moved about a mile away, to Darlaston Green! I

went to the Central Schools in Slater Street from then

on and I think I was about nine by this time.

No. 4 Bush Street had two bedrooms

and the family were Granddad Owen (also known as Captain

Owen), Granny Owen, their daughter, her husband, their

granddaughter Florence (known as Floss) and me, plus two

men lodgers. There was one room downstairs with a back

kitchen which flooded every time it rained. Upstairs

there was a four poster where Granny Owen and her

granddaughter Floss slept at the top and I slept at the

bottom. Floss's mother and father slept in the other

bedroom and Granddad Owen and the two lodgers slept on

chairs downstairs.

They cooked on the fire and washed

in bucket or bowl of cold water which was fetched from

the one outside tap, shared by the other two houses in

the yard. St George's Church, with its very overgrown

church yard, was opposite. There was a family called

Jones who lived in the Dairy, two doors down from us.

This house is still there now, no longer a dairy but

called 'The Dairy's Still'. Mr Jones, an old gentleman,

used to come into the street with a big ear-trumpet. He

would put the trumpet to his ear, listen and say "Them's

over" (meaning the German planes!) I remember sitting on

the gutter very late at night and listening for the

zeppelins.

Air raids

During the air raids we would go

down the cellar of the house next door, where a family called Kimberly lived. (This

house is still there now, next to Bowling Green Close,

on the left as you look at the Close). Mrs Kimberly

would say "bring some bread" she was always afraid we

would be blocked in! The cellar was cleaned and

whitewashed and there was a stone sill all around the

walls where we would sit. Bowling Green Close is

actually cut through the site of our house and the other

two houses in our yard.

I remember during the summer, we

children would sit on the gutter in the early morning

light, doing corking with four nails knocked into an

empty wooden cotton reel. My Dad worked for Darlaston

Council for a time but then his main job was as a

maltster for Pritchard's Brewery. Mr. S. Canlett was in

charge and his name can still be seen in a glass window

at the town hall side of The Swan pub in Victoria Road.

|

The house on the left-hand corner of Bowling Green

Close, once occupied by the Kimberly family. |

|

When I was taken in by the Owen

family, I had only ‘ill-assorted leaves-off’ for

clothes, which people would give me and this included

shoes of sorts. I was once given a white pinafore by the

family who lived at and kept the old Darlaston Post

Office. I was so naive in those days, I believed that

the rails around the top of the Town Hall, on the

right-hand side roof, looking at the building from the

front, was where the devil lived!

I also remember a teacher, Miss

Nixon, taking me to Beecham's Chemist in Darlaston to

have a wart removed from my finger. The treatment cost 1

shilling and was paid for by the teacher. This was on a

Friday and the wart was gone by school time on the

Monday. In Bush Street, towards the top end where the

Old Bush pub stood (the present one is a new building

and has now been made into a rest home (1988/89).

There was a family who had a

daughter called Serran (Sarah Ann?) and she was a very bad cripple. She used to play

on the footpath and pitifully drag herself around on her

bottom. This was just accepted as it was, nothing was

ever done about it. There was no-one to care in those

days. You just got through life as best you could.

Most Saturday nights, after the

pubs closed, there would be rows and fights and the lamp

would go flying across the room, still alight and lamp

oil would spill everywhere. That was at our house.

Sometimes, rows would be so bad elsewhere in the street

that the furniture would be thrown out on to the street

- to be recovered next day, when they'd sobered up.

The families in the other two

houses in our yard were the Stanfields next to us, in

the middle house, and the Finches on the other end, next

to a gullet which led down the side of the big house

which is still there now, on the right-hand side of

Bowling Green Close as you stand facing it. At night,

sometimes, Floss and I would walk down The Green, down

Heath Road, to the Forge called Tolleson's and Bostock.

We would watch the puddlers at work and the big furnaces

open up. The men would be sweating and would wear big

handkerchiefs around their necks. This would be on the

left-hand side, at the end of Charles Richards & Sons

works, before the extension to Charles Richards factory

was built on the site in the 1930s.

When it was growing late, one of

the men would say, "Come on girls, it's time you went

home", and he would take us home. There was never the

slightest thought of danger or mistrust, they were

staunch, honest men. Men you could trust. There was a

large chimney breast in the downstairs room, where the

table and squab were and I used to sit on a stool under

the mantelshelf, in what is now called an 'inglenook'

for hours, nursing the cat. I often got shouted at for

putting my dinner down for the cat!

Daughters

One dinnertime, Grandad Owen came

in from the pub and saw me doing this and I pulled over

a chair which caused him to fall over. I ran for my life

all the way to Moxley, to the home of some relatives of

the Owens. They were Grandad Owen's brother and his wife

and three daughters, and they lived in Queen Street,

Moxley. The husband was a kind man and let me sleep on

the squab for the night.

Two of the three daughters found me

in 1988, after about sixty years. I had forgotten them,

but I had been in their minds all those years, even

though they were so much younger than me. They had tried

several times to find me. It was lovely to know that I

had had a link with a family all down the years, after

feeling that I had been unwanted all my young life. It

is like looking back to another world. What a great pity

the people of today don't realise just how lucky they

are, whatever help they get." |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|