|

Town built on coal and

the skill of gunmakers

As if standing guard, a line of hills stretches

across the south of the Black Country, dominating the

landscape. Rising up just below Wolverhampton, they line

up in a south-easterly fashion, beginning with Sedgley

Beacon and moving on through Wren’s Nest and Dudley

Castle Hill to the Rowley Hills.

The high ground then marches

onward, although more narrowly and less pronounced, out

of the Black Country and across Quinton and Frankley

Beeches, going on to merge with the ridges of Clent and

Lickey.

Important for their limestone and

road metal, these hills were vital to the industrial

development of the Black Country and they lie on the

watershed of England. To the west, water drains to the

River Severn via the Smestow and Stour system; while to

the east the River Tame and its small tributaries flow

away to the River Trent and the North Sea.

World renowned for their geology

and fossils, these hills provide a magnificent vantage

point for the South Staffordshire Plateau. Standing up

on Kates Hill at night and looking north-eastwards, down

at the valley of the River Tame, the darkness is picked

out by a multitude of lights from countless homes and

factories in an almost magical illumination.

Attracted

In the daylight, it is clear that

this low-lying ground is broken up by low hills formed

in most cases by glacial drift and which have not been

eroded by streams. From early times, these hills in the

basin of the upper Tame attracted settlers, but the

names that we call them today are those given them by

the Angles who moved in to what is now the West Midlands

in the late sixth and seventh centuries.

There's Bilston, mentioned in Lady

Wulfrun's charter of 985 and a few years later in 996

when it was given as Bilsetnatun, meaning the farmstead

or estate - tun - of the dwellers on the sharp ridge -

bill saete.

Then there's Wednesbury, bringing

to mind Woden, the greatest of the old pagan gods, who

was the creator, the god of victory and of the dead and

who is also remembered in Wednesday. Signifying the

stronghold - burgh - of Woden, Wednesbury may not have

been mentioned in documents until the Domesday Book of

1086 but its name indicates a much older origin.

Lying between these two is another

hill settlement, that of Darlaston. Just over a mile

north west of Wednesbury and three miles south west of

Walsall, it is also unnamed in the unprecedented and

massive gathering of information ordered by William the

Conqueror - unlike the other Darlaston in Staffordshire

near to Stone.

|

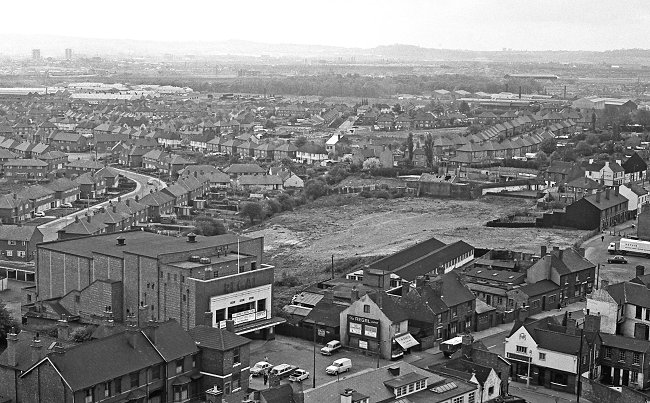

A mid 1960s view from the top of

John Wootton House looking across Darlaston to Dudley

and the distant hills. Courtesy of Bill Beddow. |

|

Mind you, that is not to say that

there was no Darlaston in the aftermath of the Norman

Conquest. It may have been included within a bigger

manor, such as that of Sedgley, or a scribe may have

missed it out by mistake. We don't know. What we can say

is that Darlaston signifies the estate (tun) of Deorlaf.

The earliest document for the place

named it as Derlaveston in 1262, although by 1316 its

modern form had emerged when it was recorded as

Derlaston. According to Sampson Erdeswicke, whose

pioneering and unpublished survey of Staffordshire was

carried out over the decade from 1593, a William of

Darlaston was lord of the manor at about the time of

Henry III, who reigned for much of the thirteenth

century. In 1801, the Reverend Stebbing Shaw brought out

an indispensable tome on the History and Antiquities of

Staffordshire, drawing on the work of Erdeswicke and

others. Fortunately he brought to light a little more

information on the history of Darlaston.

Dwelling

The first deed that he mentioned

related to Thomas lord of Darlaston transferring to Hugh

son of John de Bylestone a messuage (a dwelling house

and its surrounding property, including outbuildings)

formerly held by Amice le Peynnereste. Shaw thought that

this document also came from the reign of Henry III, and

in another deed he noted that a wood belonging to a

William de Darlaston had been destroyed of old. The

direct line of the Darlastons later died out and for a

time their old possession came into the hands of Henry

VIII when it was valued at 13 pounds nine shillings and

thruppence farthing.

Still, despite Shaw's researches,

there is little hard information about Darlaston and its

history. In Robert Plot's Natural History of

Staffordshire in 1686 it merited but a handful of

references. One related to the local iron ore which

could be made into nails, while another praised the

generosity of a Dr. Thomas Pye. Born in Darlaston, he was educated at Oxford and became a

vicar, teacher and writer in Sussex who was noted for

his learning.

In 1606, Pye visited "some

Relations at Darlaston near Wednesbury, upon occasion

that some of his Servants going to ring in the old

Steeple which was of wood and weak, had been in

danger of their lives". Accordingly, Pye offered to pay

for a tower of stone for the parish church of St.

Lawrence so long as the people of the "town" paid for

its transport. This they did and also put up an

inscription to his good-heartedness and piety.

Such references to Darlaston are

rare. Too often it was overlooked by commentators or

else it was associated with Wednesbury and given no

clear identity of its own. However, in 1698, good coal

mines were pointed out at Darlaston. It is not

surprising for it lies above the Middle Coal Measures of

the South Staffordshire coalfield, where the Thick Coal

is rarely more than 400 feet below the surface.

|

The Waggon and Horses in King Street, in the 1960s.

Courtesy of the late Howard Madeley. Gunmakers and

tradesmen had money to spend! |

Shaw himself was alert to the

importance of coal to Darlaston. He wrote that "there

are several coal pits sunk lately, and probably will

soon be more, as they have lately cut a canal through

the parish to Walsall. There is only one coal mine at

which they work now in this parish, in which the coal is

about seven yards thick. The ironstone is about three

quarters of a yard thick, and is found in the parish

under the coal.

The mines are very subject to damps. The

miners are subject to asthmatic complaints, and very few of them live to be 70

years of age. The air is sharp and dry. |

|

Nailers

"There is great plenty of brick,

tile and quarry clay; in some places not more than four

feet, and in others a great deal more. There is a mine

of clay now at work in which they have gone 13 or 14

feet deep, and it is then good. They are prevented going

deeper by water." In addition to the miners and

quarrymen, there were numerous gunlock makers and

nailers in the locality.

By 1801, Darlaston had a population

of about 3,000 people living in 600 houses. Its area was

small, encompassing just over 1,500 acres and it ranged

two miles east to west and one and a quarter miles north

to south. Of this total there were about 800 acres of

arable and pasture, upon which wheat, barley and oats

were generally grown, and 30 acres of meadow. Among the

chief buildings were the church, its schools opened in

1793, a meeting house for the "very numerous" Methodists

dating back to 1762, and another place of worship for

the Independents "who are very few".

In the succeeding years, Darlaston

continued to be ignored by observers. The Strangers

Guide to Modern Birmingham published in 1825 belied its

title by including material on many Black Country towns,

but its entry for Darlaston was brief.

Hinges

The writer declared that the place

was only one mile distant from Wednesbury and that

"neither on the road or in the village could I perceive

anything deserving of attention; the inhabitants being

employed in the same pursuits as at Wednesbury". These included coal mining, the gun

trade, the making of springs, steps and other articles

for coach makers and the production of "wood screws,

hinges, and of late, apparatus for the gas lights".

Nine years later, in his History,

Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire of 1834,

William White explained that "the manufacture of the

place is gunlocks; and there are several steel furnaces

and forges for the supply of steel for the locks and

springs that are made".

The British gun trade was focused

upon Birmingham and was marked out by its sub-divisions.

One of these was the making of locks, most of which came

from Darlaston and Wednesbury. Like most middle class

writers, this person pandered to the predilection of

middle class readers for shocking accounts of working

class behaviour. He relished in reinforcing negative

stereotypes of working class people, deploring the way

that "these Darlaston gun lock makers used to live in

the most luxurious and extravagant manner. Such was

their demand for poultry, fish, and meat, that Darlaston

became the most profitable market for these things in

the neighbourhood."

Appalled that working class people

should have the temerity to earn good money and to enjoy

themselves, the writer fulminated that the workers

"might have made fortunes in the days of prosperity, but

they not only spent what they obtained extravagantly,

but refused to work more than one or two days a week.

During this belligerent carnival

the people sunk even lower than before in vice and

immorality, and not one particle of what can be

denominated personal or household comfort, was obtained.

Bull baiting, dog and cockfighting, and all sorts of low

and debased practices, were the amusements they indulged

in, while swearing, cursing, and disgustingly foul

language, seemed to grow with their prosperity."

It is noteworthy that the writer

paid no attention to the drinking, gambling, carousing,

cock fighting and fox hunting of the upper class. Be

that as it may, he did acknowledge that "the workmen are

incredibly ingenious, being able to forge almost

anything on the anvil".

|

|

Workers at Bradley & Foster

Limited at Darlaston Iron Works. Courtesy of Brian

Groves. |

|

Wonderful

So they could. Until the late

1850s, lock making was a hand trade and according to the

1866 account of John Goodman of the Birmingham Small

Arms Company, "the several parts of each lock were

forged on the anvil by men whose wonderful skill became

proverbial". These various parts were put together by

filers and were finished by polishing and hardening.

During the long French Wars from

1791-1815, the gunlock makers of Darlaston prospered. In

1838, a short but interesting account of them was given

in Osborne's Guide to the Grand Junction Railway, which

line passed just to the east of the town and stopped at

James's Bridge. The writer stressed that during the war:

"A good workman could get a pound

note per day. Granting a considerable allowance for the

depreciation of paper money, yet the profitable

employment in making gun locks was such, that by working

only two days a week, the men could obtain as much as

would supply their wants, and find them the means of

enjoying the only luxury they seemed to know - that of

drinking four days a week - which they used to indulge,

out of loyalty to their own country, and hatred to

France."

The coming of peace in 1815 led to

a depression generally in Britain. In particular, it

brought a marked decline in the fortunes of the

Darlaston gun lock makers. Despite this the trade

remained an important one. By 1861 there were five or

six main workshops in the town, each employing about 20

skilled men; and there were between 20 and 30 little

masters. However, because of mechanisation and the

emergence of gun production in other countries, the end

was fast approaching for the trade.

In 1865, Jones's Mercantile

Directory of the Iron District included 26 gun lock

makers, forgers or filers – one of whom was a woman,

Ellen Butler, a gun lock forger and stamper of

Wolverhampton Lane. Several were also shopkeepers or

publicans. Their need for an alternative income

highlighted the adverse conditions for those involved in

making gunlocks by hand. The final blow came in the

depression which afflicted gun making after the end of

the Franco-Prussian War in 1876. Within 15 years the gun

lock trade had disappeared from Darlaston.

Some of those who lost their jobs

were taken on by the BSA in Birmingham, but

understandably they found it hard to cast off their

craft. Their foreman stated that they followed the

practices of 100 years previously, bow and breast

drilling instead of using power machinery, while they

continued to buy their own tallow-dip candles instead of

the best Russian tallow free supplied by the company.

Furthermore they "would do no more tempering after ten

o'clock in the morning, owing to their superstitious

belief, that springs tempered after that hour would

break.

The sad fate of these Darlaston men

was that of all skilled workers whose craft was

destroyed by mechanisation and it was shared by the

nailers of the town whose trade became extinct in the

same years. The harsh economic conditions were made

worse by the closing of local mines and the collapse in

the 1880s of two major employers: Bills and Mills, which

embraced blast furnaces, foundries, metal processing,

and coal mines; and Addenbrooke, Smith and Pidcock, coal

and iron masters.

Battered by hard times, Darlaston's

population fell from 14,739 in 1871 to 13,900 ten years

later. Fortunately new jobs soon arose because of the

adaptability of some of the town's gun lock makers, such

as William Wilkes of Eldon Street. By 1865, he had also

moved into the production of nuts and bolts, as had John

Archer and Son of Great Croft Street and Pinfold Street.

There were another 15 businesses involved in this trade.

They laid the foundation for Darlaston to push itself to

the fore as the nuts and bolts capital of the world.

|

Workers at Ward's clay pit in the

1930s. Courtesy of John & Christine Ashmore. The

fine glacial sand and clay deposits in Darlaston were

exploited for fine moulding sand for the foundries, and

clay for bricks and clay pots. John Wilkinson was

probably the first person to use moulding sand from

Darlaston, as long ago as the late 18th century. |

|

Expanded

For many years, this industry was

characterised by small scale operations. In 1851

Alexander Cotterill was the largest employer with just

fourteen men. A decade later he had expanded to give

work to 75, but within a few years such a number had

been dwarfed by those employed in large factories. By

1911, around 6,000 people were engaged in making nuts

and bolts in the Black Country, the great majority

of them in Darlaston. Perhaps half

of them were employed by Guest Keen and Nettlefold's,

which had taken over the Atlas Works at the turn of the

20th century.

Until 1890, places such as this had

supplied nuts and bolts for railways in the British

Empire. As this market dropped off, massive demand came

first from the rapidly expanding electrical engineering

and machine tool trades and second, after 1900, from the

motor industry.

Another proud Darlaston company

also pushed itself into the limelight in this period

through its innovation, design and quality products. It

was Rubery Owen. Back in 1834 a Jabez Rubery had been a

gun lock filer, screw turner and gun lock maker. Fifty

years earlier the brothers J. T. and T. W. Rubery had

started a factory in Booth Street for making light steel

roof work, fencing, gates and the occasional bridge.

Later T. W. Rubery left the business, and in 1893 his

brother went into partnership with Alfred Ernest Owen. A

young engineer of talent, foresight and determination,

Owen transformed the company. Alert to the rise of new

industries and to the potential for supplying them with

new products, he oversaw the making of an award winning

chassis frame for a car made from rolled sections and

solid round steel bars.

Shadow

In 1910 Owen became sole owner and

with his acute vision he added an aviation department,

so allowing Rubery Owen to supply small aircraft

components in the First World War. By that time, his

company was also making car wheels and had taken over

Chains Limited of Wednesbury and Nuts and Bolts Ltd of

Darlaston as well as two Birmingham businesses.

Alfred Ernest Owen died in 1929. He

was followed ably by his two sons, Sir Alfred and E. W.

B. They led a highly skilled, motivated workforce that

helped the people of Darlaston withstand the ravages of

the Depression of the 1930s and which played a vital

role in the Second World War. Rubery Owen's structural

department at Darlaston was responsible for building

shadow factories, aircraft hangers, Bailey bridges, tank

landing craft and components for the Mulberry Harbours

that were so essential to the success of the Normandy

Landings.

During the same period, the motor

frame department made gun carriages, projectiles, mines

and bomb-trolleys; the motor wheel department produced

instrument containers, bomb carriers, anti-submarine

weapons, bomb tails and much more; while the aviation

department turned out nuts and bolts for aircraft.

After the war Rubery Owen continued

to expand, but like all Black Country manufacturers it

suffered badly because of the economic problems of the

1970s and unhappily its main plant closed in 1980.

The year before the GKN factory had

shut down. Just as a century earlier, Darlaston and its

people were buffeted by a severe economic downturn.

Unfortunately, unlike then, no new industry appeared to

provide manufacturing employment. With the massive loss

of jobs locally, the town centre also declined, but

Darlaston and its folk are resilient and hardy, and are

resolved to work for the best of their town.

In the fore of that movement is

Darlaston Local History Society. They have striven to

let younger generations know about the past of the town

and have brought out a number of important publications.

Darlaston, like all the Black

Country towns, punched well above its weight for over a

century on the world stage and through the ingenuity,

innovation, adaptability, prowess and hard graft of its

people it made the world take notice of itself.

Let us hope that it can do so

again.

|

|

The sun sets on Darlaston's

industry. Bradley and Foster's furnace in the 1970s. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|