|

Number 11 Factory Street, a

typical house in the area. |

Many of the houses were still

without a mains gas supply and so oil lamps had to be

used at night. They were hung from the ceiling and often

filled the rooms with an unpleasant acrid smell. Soot

from them would be deposited on the ceiling above,

eventually producing a black mark. Often just a single

lamp would be used upstairs, usually hanging from the

landing ceiling, so as to illuminate the stairs, and

light the bedrooms through open doors.

Coal fires were an essential part

of life, and the chairs in the sitting room (often the

kitchen) would be arranged around the fire in order to

get the most benefit from it.

Coal was delivered by the coal man

in 1cwt sacks, and tipped into the cellar through the

coal hole, or stored in a coal house, or coal place as

it was sometimes known. It would be stored in piles,

each consisting of lumps of the same size. Bundles of

kindling wood made from

off-cuts could be cheaply purchased from many shops, and were often stored with the coal.

Everyday, a bucket or coal scuttle would be filled and

placed by the fire in readiness for use. The grate was

swept clean with a small brush to remove any ash from

the previous day’s fire, and a few crumpled newspaper

pages and criss-crossed pieces of kindling wood were

positioned in the centre. They were covered with smaller

lumps of coal, known as “slack”, and larger lumps were

placed around them. The paper could then be lit to start

the fire. |

| Often a coal shovel would be fanned in front of the

grate to produce a draft to draw air over the fire to

quickly get it going. Lighting a coal fire is a

practiced skill, something that we have almost forgotten

today.

Throughout the evening, as the fire burned, other

pieces of coal would be added. The quality of the coal

could vary considerably. Good black coal often burned

better, and at a higher temperature than the browner

Lignite. Sometimes small pieces of fossilised leaf, or

other stony material would be embedded in the coal. When

they heated and expanded, they could shoot out of the

fire and possibly put a burn mark on the carpet. Often a

mesh fire guard would be used to prevent this, and also

to keep small children safe from the fire. The larger lumps of coal,

often including bits of shale were known as “bats”. |

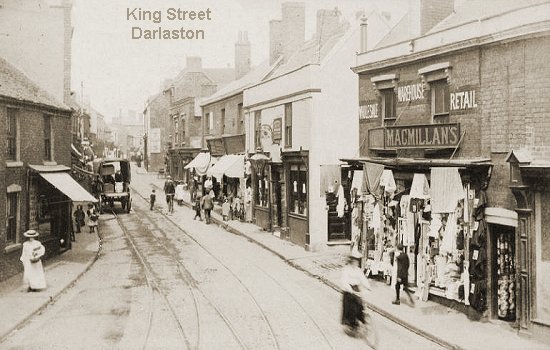

King Street, from an old postcard.

| A large blazing fire would more

than adequately heat a whole room, but as the evening

progressed the state of the fire greatly changed. Later

in the evening when much of the coal was consumed, the

temperature would fall. Because of this people tended to

sit around the fire, and their rooms were laid out

accordingly. Occasionally the chimney sweep would be

called to sweep the chimney and remove the soot which

was a fire hazard. Soot burning in the chimney could

cause a lot of damage, and a large build-up of soot

could fall down the chimney and blacken everything in

the room below. Coal fires were dusty and dirty and so

rooms had to be dusted and cleaned more frequently than

today. Bath night usually occurred once a

week because a fire had to be made to heat the water.

People bathed in a tin bath, either in the brewhouse or

in front of the fire in the kitchen. Because of the time

taken to heat the water, the same water would often be

used by several people, and topped-up with hot water as

necessary. |

A podging tool. Courtesy of Beryl Jones.

|

Carpets were a luxury. They were

usually podged rugs (sometimes called bodged rugs) that

were hand made using strips of old material, threaded

through a course Hessian backing with a podging tool,

consisting of a steel rod with a hook at one end and a

wooden handle at the other. Most of the family joined in

the rug-making which could be a good way to while away

the long winter evenings. An old sack would be saved and

washed to form the backing and a podger could be made

from half an old clothes peg. They often used darker

material which did not show dust and dirt, and sometimes

formed a pattern from several colours. The finished rug

would take pride of place in front of the hearth and

would be a treat to walk on, especially when compared

with the cold quarry tiles that frequently covered the

floors.

Cooking was a very different

process to what we know today. Some families were lucky

as their houses were connected to the gas supply, and so

might even have a gas cooker. Most would cook on the

kitchen range, having to cope with the vagaries of the

fire and the changing temperature. Pots would be hung

over the fire, or placed in the small oven that usually

formed part of the range. The fire also heated the

kitchen, often the only heated room in the house, which

usually doubled as the living room.

Some food would be washed and

prepared at the sink in the brewhouse, before being

carried into the kitchen to be cooked. Fruit and

vegetables were seasonal and so homemade preserves such

as jam and pickles were an important part of the diet.

Food was stored in the pantry, a

dry, cool, and dark room, with a large stone slab and

plenty of shelf space. If you didn’t have a pantry it

could be stored in the cellar, which would be

partitioned to separate it from the coal. Many families

kept chickens in their back yard to provide them with a

frequent supply of eggs, and meat on special occasions. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Woman's Work |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Hobbies etc. |

|