|

A Prefabricated Home of

Your Own

In the 1930s and 1940s the country

suffered from a severe housing shortage, which resulted

in large numbers of new houses being built. In the late

1940s one solution to the problem was to build

prefabricated houses consisting of a kit of parts that

were built in a factory, and taken to the building site

for rapid erection. Darlaston’s largest engineering

firm, Rubery Owen & Company Limited realised that a

lucrative market existed for cheap factory-built houses,

and so the company’s Structural Department began to

produce good quality houses for sale to local

authorities and building companies. |

|

Background

In the late 1920s and early 1930s

large numbers of people still occupied old Victorian

slums, which had few modern amenities. The 1930 Housing

Act introduced a five year programme for the clearance

of slums, with designated Improvement Areas. Local

authorities were required to provide suitable housing

for anyone whose home was demolished in the slum

clearance. This led to the provision of council housing.

As a result of the Act a total of 19,840 houses had been

demolished by the summer of 1934.

Although many houses were built in

the 1930s, the problem still remained, and was made

worse by the increasing population. The building

programme temporarily came to an end at the outbreak of

the Second World War, and didn’t start again until the

war ended in 1945. During the war thousands of houses

were destroyed by enemy bombs, which made the problem

even worse. In 1945 it was estimated that around 750,000

new houses were required.

The post-war Labour Government

instigated a housing programme that relied on local

authorities to provide the much-needed housing, and

large building projects were soon underway. Part of the

solution lay in the large-scale construction of

‘prefabs’, a scheme that was instigated by the

government’s Temporary Prefabricated Housing Programme.

Most of the ‘prefabs’ were small

factory-built, single storey temporary bungalows with a

life expectancy of just 10 years. Although around

156,000 of them were built, there was still an acute

housing shortage. Local authorities still had to provide

a range of houses to cater for different sized families,

and so the conventional ‘prefabs’ could only fill part

of the housing gap.

The Rubery Owen houses, unlike the

basic ‘prefabs’, had a very long life expectancy, and

offered the inhabitants a more spacious, and comfortable

lifestyle. They were also ideal for larger families.

Rubery Owen Houses |

|

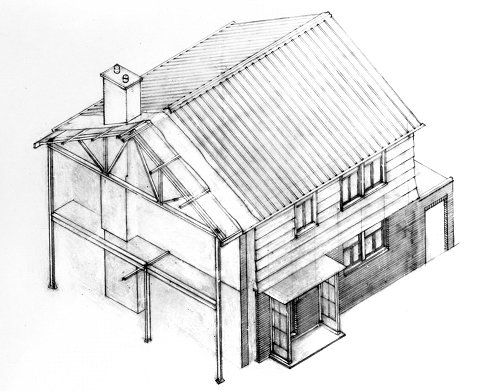

A Rubery Owen prefabricated house. |

|

An advert from the mid 1960s. |

Rubery Owen was in an almost unique

position to produce factory-built houses. The company’s

Structural Department had been responsible for a number

of prestigious developments including the London

Passenger Transport Offices in Westminster (the tallest

building at the time in London); the Palace Court Hotel

in Bournemouth; and numerous factory buildings.

The company also produced a

considerable number of domestic items such as stainless

steel and vitreous enamelled sinks, and cupboard units.

The company’s wealth of technical

knowledge and practical experience came together to

produce a good-sized building that struck a balance

between the sound methods of traditional building, and

the ease and speed of erecting factory produced units.

The architects were A. T. and

Bertram Butler of Dudley and Wolverhampton who were

responsible for many of the area’s landmark buildings

including Dudley’s Technical College, Station Hotel, and

the Guest Hospital. |

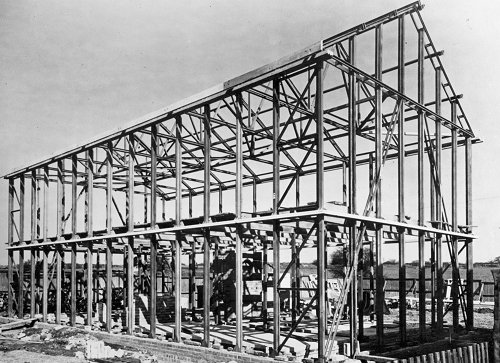

| The houses were built around a rust-proof light

steel frame with stanchions, trusses, and beams of a

substantially rectangular form.

To simplify and speed-up the building process, the

design included simple forms of attachment for almost

any suitable building material.

The individual members of the steel structure were

produced by bending, pressing or rolling, and the

individual components were welded together at the

factory. |

The light steel frame. |

|

A partially-built house showing

the steel frame beneath the external cladding. |

On the building site the individual and lightweight

sections of the steel frame could be simply bolted

together, and the large floor, wall, ceiling, and roof

panels quickly added, so that the building could be

assembled in a very short time.

The total weight of the steel frame was 1¾ tons per

house, and the maximum weight of each section was 80

lbs.

As a result there was no difficulty in transporting

the various parts to the building site. |

| Several versions with minor differences were

produced. The type 'B' and the type 'C' are shown below: |

| The type 'B' has a downstairs

toilet and a fuel bunker on the side of the house. |

|

|

The type 'C' has an upstairs

toilet, a slightly shorter third bedroom, and a fuel

bunker on the back of the house. |

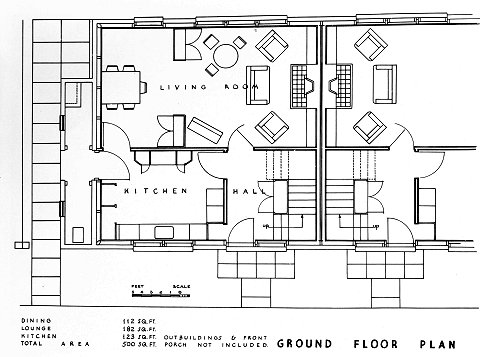

| The type 'B' ground floor plan

showing the open-plan living room and dining area, the

kitchen with its built-in cupboards, the compact

staircase, and outside toilet. |

|

|

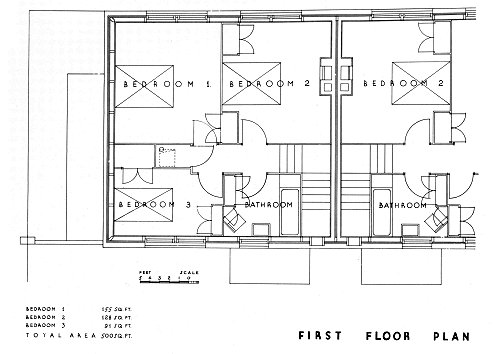

The type 'B' first floor plan

showing the reasonably sized bedrooms and bathroom, with

fitted cupboards, and the landing cupboard; presumably

an airing cupboard. |

|

Conventional concrete and brick

foundations were used with pockets to receive the

holding-down bolts for the steel stanchions. The bolts

were positioned using a steel template that came with

the kit of parts. The base of the steel frame was

mounted on a slate damp-proof course, set in

cement. The wooden sub-frames and steel casements for

the windows were bolted to the stanchions, and an 11inch

brick cavity wall was added to provide the necessary

sound insulation.

The roof could be covered

immediately after the frame was erected with coloured

combined asbestos sheeting, and the pre-formed

light-gauge steel staircase quickly added. The staircase

was fitted with wooden treads and risers at the factory,

and transported to the building site in three sections.

The plumbing and electric wiring

were also pre-fabricated in the factory. Every room had

at least one power point, and each house came complete

with a wireless earth and aerial. The kitchen and main

bedroom had points for extension loudspeakers, and fixed

electric fires were fitted in the dining recess, bedroom

number 2, and high-up in the bathroom. |

|

The kitchen included the following

fittings:

A slow combustion stove.

An electric cooker.

A refrigerator.

A wash boiler.

A sink and double drainer unit with cupboards below.

A larder.

A china and dry store.

A cupboard for a broom and cleaning materials.

The slow combustion stove provided

hot water, and heated bedrooms 1 and 3 via hot air

ducts.

It also heated the dining recess

and living room via a coil that was fitted in the dining

recess area. |

A partially completed house

showing the roof covering, with the garden gate and wall

on the right. |

|

Wet construction processes were

kept to a minimum to ensure that assembly could be

undertaken in all weathers.

The end result was a comfortable,

reasonably sized family home that was much faster to

build, and far cheaper than a traditional house, and more

spacious than a conventional ‘prefab’. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|