|

Background

Dud Dudley was a pioneer in the

iron industry, the first man to successfully use coal to

produce iron by melting iron ore in furnaces, with

bellows, although only in small quantities. Iron had

been traditionally produced using charcoal, made from

the wood that came from the plentiful forests that grew

locally. This couldn’t last because trees were being

chopped down at an alarming rate, leading to

deforestation. There were vast coal and iron ore

deposits in the area, so coal would seem to be the

obvious fuel for smelting iron.

The problem with this is the high

sulphur content in coal. Any iron smelted with coal

would contain sulphur, which had little short term

effect when producing castings, but led to

deterioration. The sulphur content was disastrous when

making wrought iron. Much of the iron produced was

wrought iron, but the high sulphur content from the coal

caused the iron to crumble when it was being worked

under the smith’s hammer. The use of coal in a blast

furnace only became possible after the introduction of

the hot blast, by James Beaumont Neilson in 1828. This greatly

increased the hearth temperature and enabled the sulphur

to be removed as calcium sulphate from the slag.

In the 1700s, Abraham Darby, a relative of Dud Dudley, developed coke-fuelled

blast furnaces to produce good quality iron, which led

to the growth of the Shropshire iron industry. His

great-grandmother Jane, was Dud Dudley’s sister.

Little is known about the process

used by Dud Dudley in his iron making, which was kept

secret, but it was unlikely to have involved the use of

coke because the local thick-seam coal slack, which he

often referred to, is non-caking. Coal is not as

combustible as charcoal and it would have been difficult

to produce an adequate blast for a coal-fired furnace

using the crude blowing apparatus existing at that time.

He did rely on extra large bellows to increase the

blast, and extra blasts, but his furnaces and the

bellows have not survived. He certainly produced cast

iron in small quantities, but it is unlikely that it

would have been very profitable.

Dud Dudley

Dud Dudley’s parents were Edward

Sutton, 5th Baron Dudley and his mistress, Elizabeth

Tomlinson, with whom he had at least 11 illegitimate

children. They lived at Himley Hall, then a moated manor

house. Dud was born in 1599 and was given a lease of

Chasepool Lodge in Swindon, near Wombourne. Edward

looked after his children well and educated them

carefully, before employing them in the management of

his extensive properties.

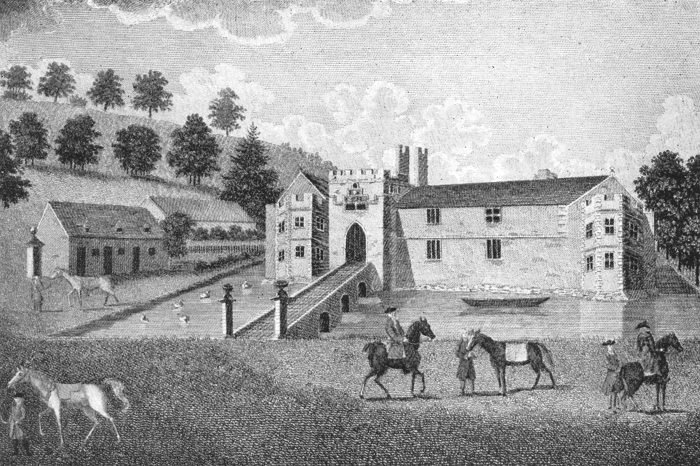

Himley moated manor

house, where Dud lived as a child. An

engineering drawing by Ravenhill, from

'Dudley' by G. Chandler and L. C. Hannah.

|

Dud took great interest in his

father's ironworks near Dudley, and obtained

considerable knowledge of the various processes

involved. He was a special favourite of his father, who

encouraged his interests in the improvement of iron

manufacture, and sent him to Balliol College Oxford, to

obtain an education that would help to turn his

excellent practical abilities to good use. He was there

until 1619 when his father sent for him to take charge

of an iron furnace and two forges at Pensnett.

After taking charge of the factory,

he discovered that wood for making charcoal was in short

supply, so he began to look into the possibility of

using coal, then known as pit coal, as a substitute. Dud

altered one of his furnaces to burn coal and carried out

a trial run. He was quite satisfied with the result and

decided to persevere, carrying out the same procedure as

before but with the addition of a second blast to

increase the active combustion of the fuel. He felt that

the small quantity of iron produced was of good enough

quality to be sold and so he wrote to his father, then

in London, to inform him of what he had done. He asked

him to obtain a patent for the invention from King

James, which was granted as patent No. 18, dated the

22nd February, 1620 and taken out in the name of

Lord Dudley himself.

Dud proceeded to produce iron in

this way, both at Pensnett and Cradley, where he built

another furnace. The following year he sent a quantity

of the new iron for testing, to the Tower of London,

following a command by the king. After the tests it was

pronounced to be good merchantable iron and so there was

every prospect that the new method of manufacture would

become established. He hoped that further improvements

could be made, but due to a succession of calamities,

manufacture came to an end.

The first calamity was a flood,

known as the "Great May day Flood" which destroyed his

main factory at Cradley and caused a lot of damage in

the area. Dud later recorded that part of Stourbridge

was deep in water: "At the market town called

Stourbridge," says Dud, "….although the author sent with

speed to preserve the people from drowning, and one

resolute man was carried from the bridge there in the

daytime, the nether part of the town was so deep in

water that the people had much ado to preserve their

lives in the uppermost rooms of their houses."

The next calamity came because the

hostile local iron smelters hoped that the flood had put

an end to Dud's pit coal iron making. They had seen

him making good iron by his new patent process, and

selling it at a cheaper price than they could manage.

They began to spread the word that his iron was bad and

not fit to be used. The iron smelters even appealed to

King James to put a stop to Dud's work, but Dud quickly repaired his

furnaces and forges after the flood, at great cost and

after a short time was making iron again. A fresh outcry

came from the local iron smelters who again appealed to

the king, who commanded Dud to send samples of all the

types of iron that he made to the Tower of London, as

quickly as possible for testing. The iron smelters were

unsuccessful in their efforts until 1624 when they

managed to limit Dud’s patent to 14 years instead of 31.

Dud carried on regardless and

accumulated a large stock of merchantable iron and sold

it for £12 per ton. He also made all kinds of cast iron

wares including brewing cisterns, pots and mortars. He

continued to have problems with the local iron smelters

who began to take out lawsuits against him and succeeded

in getting him ousted from his ironworks at Cradley. He

then set up a pit coal furnace at Himley, from where he

sold pig iron to charcoal ironmasters. He also built a

large furnace at Hasco Bridge (usually known as Askew

Bridge), on Himley Road. The furnace was built of stone,

27 feet square, with an unusually large bellows,

enabling 7 tons of iron to be produced per week. At the

time it would be the greatest quantity of pit coal iron

ever made in the country. Dud also opened a coal mine

above a 10 feet thick seam, lying over a large deposit

of ironstone.

When the factory had just been

completed, a mob of rioters, instigated by the charcoal

ironmasters, broke-in and destroyed everything, even

cutting the new bellows into pieces. Dud was attacked by

mobs, received countless lawsuits against him and was

eventually overwhelmed by debt. His creditors seized him

and took him to London, where he was held a prisoner in

one of the Compter prisons for debtors, for several

thousand pounds, until his patent expired.

|

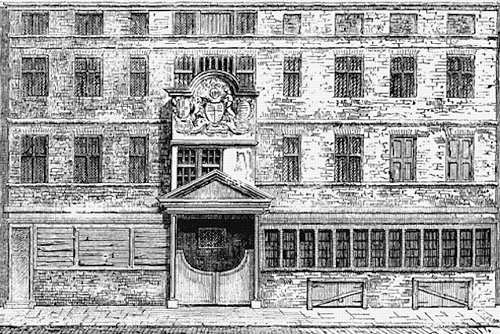

|

Wood Street Compter, London. |

The compters were terrible places, each run by a

sheriff and his staff, who charged the prisoners for

everything necessary for their survival and comfort,

including food, drink, clothes, bedding, heating and

medicine. Conditions were awful, many inmates died

from disease. |

|

Dud sought employment as an

adventurer with the court of Charles I and in 1637 was

sent by the crown on a mission to Scotland. The king seems to have taken pity on the

suffering inventor and granted him a renewal of his

patent in the year 1638. Dud obtained the patent with

three other partners; Sir George Horsey, David Ramsay,

and Roger Foulke. Soon after this happened, Dud became

involved in the army, supporting the king, and within a

few years the country was in turmoil when the Civil War

began.

Dud later claimed the manor of Himley, because his

father had at one point put it in his name, probably to

avoid it being seized by his creditors. This led to

Chancery proceedings, which he lost, and resulted in him spending time in

prison for contempt of court.

The Civil War

When the Civil War began in 1642,

Dud joined the Royalist side, supporting the king. As

previously mentioned, he had been employed by

the king in 1637 and was sent on a mission to Scotland.

In 1639 he accompanied the king on his expedition across

the Scottish border in the first Bishops’ War and was

present at the battle of Newburn in August 1640, when

the English army was defeated by the Scots.

Dud abandoned his ironworking and

became surveyor of the Mews or Armoury in 1640. In 1642

when the king left London to start his campaign, Dud

went with him and was present at Hull, when the king

went there to acquire arms that were stored in the weaponry

depository used in the previous Scottish campaigns. When

the king and his men arrived, Sir John Hotham, the

military governor appointed by Parliament, refused to

let them enter the town, and when Charles I arrived with

more men, they were driven off. Dud was also there when

the king raised his royal standard at Nottingham, and

also at Coventry, where the townspeople refused the king

entrance and fired on his troops from the city walls.

Dud also took part in the first

pitched battle of the war at Edgehill, on the 23rd

October 1642, which proved inconclusive, with both

Royalists and Parliamentarians claiming victory. After a

second field action at Turnham Green, the king withdrew

to Oxford, which became his base for the rest of the

war. Dud was in most of the battles that year, and also

acted as military engineer, supplying arms, shot and

cannon to the king’s forces at Stafford, Worcester,

Oxford and Dudley Castle.

Dud took part in the taking of

Lichfield and was made Colonel of Dragoons. He

accompanied the Queen with his regiment to the royal

headquarters at Oxford. In the autumn of 1643 he was at

the siege of Gloucester, followed by the first battle of

Newbury and later at Newport. In 1645 he was appointed

general of Prince Maurice's train of artillery, and

afterwards held the same rank under Lord Ashley. He was

taken prisoner at the end of the Siege of Worcester and

later released. When the first Civil War ended in 1646,

most of the Royalists who had fought in the First Civil

War gave their word not to bear arms against Parliament,

but when the war started again in 1648, the

Parliamentarians showed little mercy to those who had

brought war to the country again.

Nothing was heard of Dud until 1648

when he again joined the king’s forces. He proceeded to

raise 200 men, mostly at his own expense. They were no

sooner assembled in Bosco Bello (Boscobel) Woods near

Madeley, than they were attacked by the

Parliamentarians, and dispersed or taken prisoners. Dud

was taken prisoner and first marched to Hartlebury

Castle. Dud stated that 200 men were dispersed, killed,

and some taken, namely Major Harcourt, Major Elliotts,

Captain Long, and Cornet Hodgetts. Major Harcourt was

miserably burned with matches and the others were

stripped almost naked and marched to Worcester, where

they were kept close prisoners, with double guards both

at the prison and in the city.

Dud and Major Elliotts contrived to

break out of the prison and made their way over the tops

of the houses, passing the guards at the city gates, and

escaped into the open countryside. They were hotly

pursued and travelled during the night, hiding in trees

during the day. They succeeded in reaching London,

but were soon recaptured. Major Elliotts and Dud were

taken before Sir John Warner, the Lord Mayor. The

prisoners were sentenced to be shot to death, and

closely confined in the Gatehouse at Westminster, with

other Royalists.

On the day before their execution,

the prisoners formed a plan of escape. It was 10 o’clock

on the morning of Sunday the 20th August, 1648, in

'sermon time'. They overpowered the guards and Dud,

along with Sir Henry Bates, Major Elliotts, Captain

South, Captain Paris, and six others, managed to escape.

Dud received a wound in one leg and could only walk with

great difficulty. He proceeded on crutches, through

Worcester, Tewkesbury, and Gloucester to Bristol. On the

way he was fed for three weeks in 'an enemy's' hay mow

and was unrecognisable, as the helpless creature,

dragging himself along on crutches. He reached Bristol

safely and hid under the name of Dr. Hunt, a medical

doctor.

After the War

Dud lived in great secrecy until

after the execution of Charles I in January 1649 and the

end of the Royalist campaign in 1651. He then gradually

emerged from his concealment. His military career was

now over and he was penniless, reduced to a state of

utter destitution. His estate had been sequestrated by

the government, for treason, including Green Lodge and

his home in Worcester, where his sickly wife was turned

out of doors. His ironworks were also destroyed. Dud succeeded in finding two local

businessmen to join him as partners in an ironworks,

which they planned to build at Clifton. They were Walter

Stevens, a linen draper, and John Stone, a merchant.

Work was well under way on the new factory, when Dud

quarrelled with his partners and the scheme came to an

end.

Dud wrote the following about his

partners: 'They did unjustly enter Staple Actions in

Bristow because I was of the king's party; unto the

great prejudice of my inventions and proceedings, my

patent being then almost extinct, for which and my stock

am I forced to sue them in chancery.' He also wrote

that: 'Cromwell granted several patents and an act for

making iron with pit coal in the Forest of Dean, where

furnaces were erected at great cost.'

|

|

Dud was invited to visit the

furnaces and inspect the operations there by the owners,

who hoped that he would explain his secret process to

them. Try as they may, they could not discover how his

process worked and he stated that they would never

succeed in making iron profitably by the methods they

were using. The furnaces failed, as did the operations

at Bristol. Dud then asked Charles II, for a renewal of

his patent, but the king was besieged by many other

similar applicants, so Dud failed in obtaining the

renewal of his patent, whereas others were granted a

patent to make iron with coal.

Dud continued to petition the king,

asking to be restored as Sergeant at Arms, Lieutenant of

Ordnance, Surveyor of the Mews or Armoury, and also to

be appointed Master of the Charter House in Smithfield,

professing himself to be willing to do anything to make

a living.

After sending several petitions in 1660, he

was reappointed to the office of Sergeant at Arms and

his estate was returned to him. Some time later he was

again living at Green's Lodge, Swindon,

just south of Wombourne. Dud stated that nearby were

four forges: Green's Forge, Swin Forge, Heath Forge, and

Cradley Forge, all of which he operated.

|

|

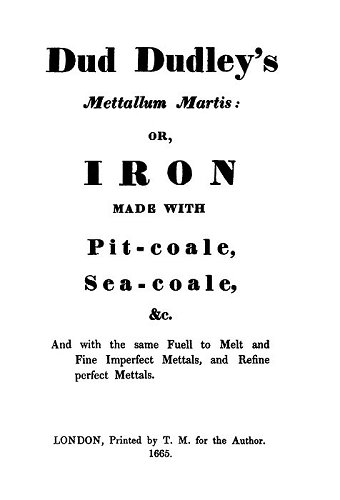

In 1665, at

the request of his nephew Edward Parkhouse, Dud wrote

his treatise 'Metallum Martis', from where much of the

information about Dud comes.

It is possible that it was

written to impress the king and give more weight to his

petitions. Also to impress possible investors.

Dud then disappeared from sight.

He married his first wife, Eleanor Heaton, (1606 to

1675), on the 12th October, 1626 at St. Helen's Church,

Worcester.

Dud eventually retired to St. Helen's in

Worcester, where he died in 1684, in his 85th year. He

lived at 44 Friar Street, Worcester, where he had a

house that was previously owned by Eleanor Heaton’s

family. After her death, he married again and had a son

in his old age. |

44 Friar Street, Worcester. Now

a café. |

|

St. Helen's Church, Worcester. |

Dud was buried in St. Helen’s parish

church in Worcester, where he erected a monument to

himself, now destroyed. It carried the following

inscription:

Colonel Dud Dudley, son of the late noble Edward of

Dudley, dear to his father and most faithful subject and

servant to His Majesty the King, in vindicating the

church, in fighting for English law and liberty; often

captured, in the year 1648 once condemned nevertheless

not beheaded; born again, as an old man he sees an

unshakeable crown.

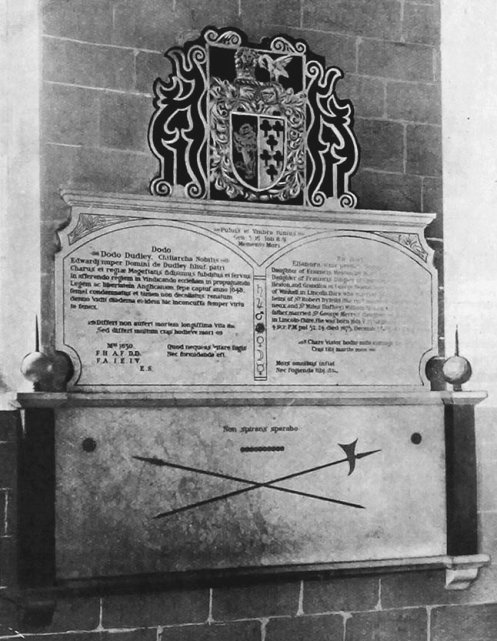

|

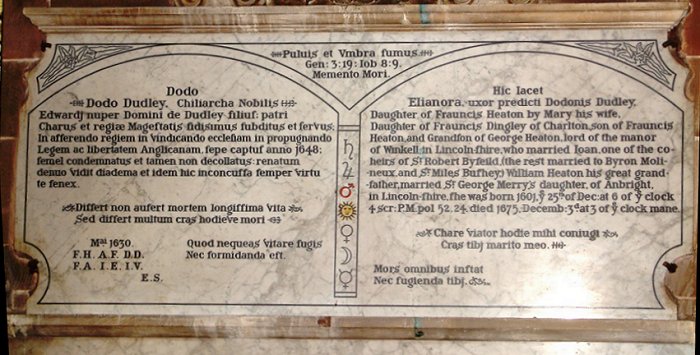

| Dud Dudley and Eleanor’s surviving monument is in the current

church

kitchen. The monument is

unusual as it contains chemical symbols written in Latin, including a list

of

metals: lead, tin, iron, gold, copper, silver and mercury. The monument was restored in 1911 by the Staffordshire

Iron and

Steel Institute. |

The existing monument to Dud and

his wife Eleanor, in St. Helen's Church. |

|

The inscription on the monument. |

|

Dud and his schemes had not been

liked by some members of the Sutton family. A relative

of his, John Bagley, accused him of wasting his father's

fortune on his coal mining schemes and bringing his

father to such destitution. His mother Elizabeth was

clearly aware of his nature and in her will she

requested that the money belonging to her, which was

passed-on to Dud, five years before her death, be given

instead to the poor people of Dudley. She also mentioned

in her will that Dud was not to see either her will or

her personal correspondence or diary. Dud did contest

his mother's will and claimed that he should own the

land where his industries stood, and also demanded the

ownership of Tipton Park and Parkfield, which Elizabeth

had owned.

Dud kept his iron smelting process a secret, not even

describing it in his 'Metallum

Martis'. He was never able to make more than five

tons a week on average, so his process never made a lot

of money. The high sulphur content in his iron meant

that it was not as good as that produced with charcoal.

He led an interesting and troubled life, and was lucky

to have survived the Civil War.

|

|

Return to the

previous page |

|