|

The Black Country was ideally

situated for the production of iron, especially from the late 18th

century, through to the 20th century. Demand was

extremely high in the many manufacturing industries that

soon appeared and the raw materials consisting of coal,

iron ore, and limestone were all available locally in

vast quantities. Thanks to the building of the large

canal network, some good roads, and the coming of the

railways, transporting heavy iron products was

relatively fast and cheap. Many people worked in the

ironworks. It was estimated that in Dudley alone, around

500 men and boys worked in iron production in 1852.

The main producers of iron in

Dudley

Blowers Green Iron Works was

established in 1800 by the Grazebrook family and by 1844

around 177 to 180 tons of iron were produced each week.

In 1851 the business was run by Michael and William

Grazebrook.

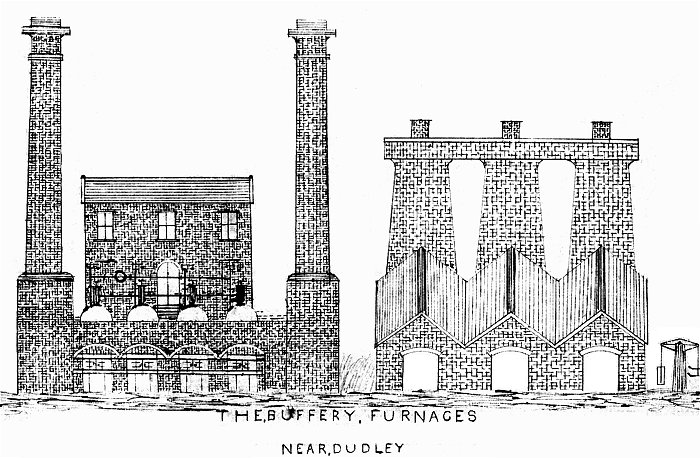

Buffery Furnaces had two ironworks,

Old Buffery Furnaces and New Buffery Furnaces. The

ironworks were located beside Bumble Hole Road,

Netherton and a short branch of the Dudley Canal that

ran north westwards from the Bumble Hole. Old Buffery

Furnaces was started by Samuel Ferriday who ran Ferriday

& Company. The business was declared bankrupt in 1817.

It was later run by Richard and Edward Salisbury. By

1855 it had been taken over by Joseph Haden, but had

closed by 1865. New Buffery Furnaces had opened by

1817 and were run by Wainwright and Jones. The factory

had closed by 1886. |

This drawing, made by J. N.

Onslow in 1913 was owned by the late David Evans.

David was unsure about the accuracy, but they are

the only images of the furnaces that are known to

exist. |

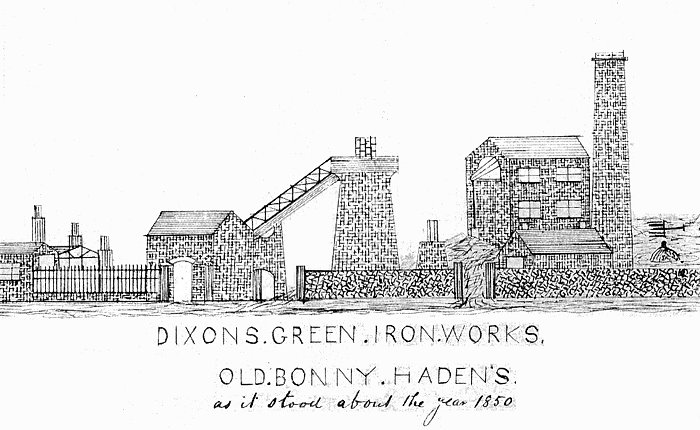

| Dixons Green Ironworks was run by

William Haden from 1835 until 1867. It had only one

furnace and closed down in 1873. |

|

Another drawing, made by J. N.

Onslow in 1913 that was owned by the late David

Evans. |

| Hingley & Smiths Ironworks was

opened in 1847 by William Jefferies at Harts Hill. In

1848 an iron boiler exploded, killing 40 men and boys.

In 1881 it became known as Hingley & Smiths when Noah

Hingley & Sons Limited acquired the business.

Old and New Netherton Iron Works. The Old

Netherton Iron Works was originally known as The

British Iron Company. The Old and New Works later

worked in conjunction and in 1844 were producing

around 180 to 190 tons of iron each week. In 1845

the business was run by Benjamin Best and by 1851

the agent was George Thompson. The business was

later taken over by Noah Hingley. The New Iron

Works produced around 18,000 tons of pig-iron per

year, which was sent to the Old Works for conversion

into the iron that was used at Hingley’s factory.

Parkhead Furnaces was

run by Parks & Company in 1806. In 1843 the business

was taken over by Edward Evers. It was a small scale

affair producing just 70 to 75 tons of iron per

week, with one furnace that used the hot blast

system. The business was still in existence in 1851.

Russell's Hall Ironworks

was run by Samuel Holden Blackwell and his father

John Kenyon Blackwell in

1827. Russell's Hall Works was known as ‘The Dock’

and in 1844 was producing around 210 to 220 tons of

iron each week. John Kenyon

Blackwell retired in 1848 leaving his son Samuel in

charge. Samuel had been born in Worcester on the 8th

May, 1816 to John Blackwell and his wife Elizabeth.

In 1861 Samuel, a widower, was living in

Wellington Road, Dudley.

He owned numerous blast furnaces,

mills and forges in the Dudley area and collieries

in Monmouthshire, along with iron ore mines in the

Forest of Dean, Exmoor and elsewhere. He was greatly

interested in geology, particularly in the South

Staffordshire Coalfield and was a member of the

Institution of Mechanical Engineers and one of the

Vice-Presidents. In 1852 he read a paper to the

Institution about utilising the waste gas from blast

furnaces.

He died at Birmingham on the 25th

March, 1868, at the age of 51, after a long and

painful illness. On his death, Russell's Hall

Ironworks closed.

Withymore Iron Works was

run by Benjamin Best in 1844 and produced around 180

to 190 tons of iron per week. By 1851 it was being

run by Benjamin Best, Barr and Northall. Francis

Northall was the furnace manager.

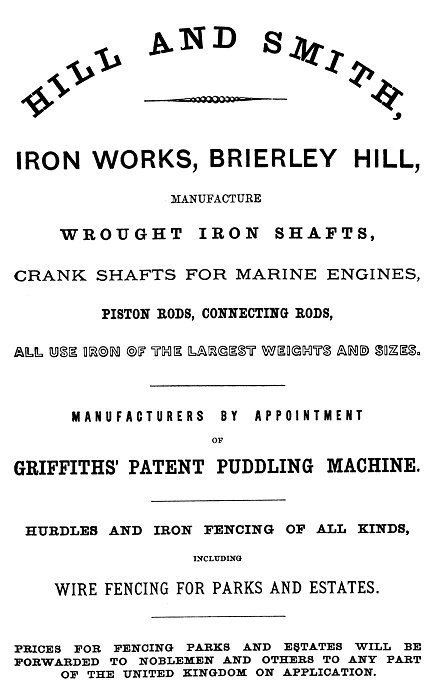

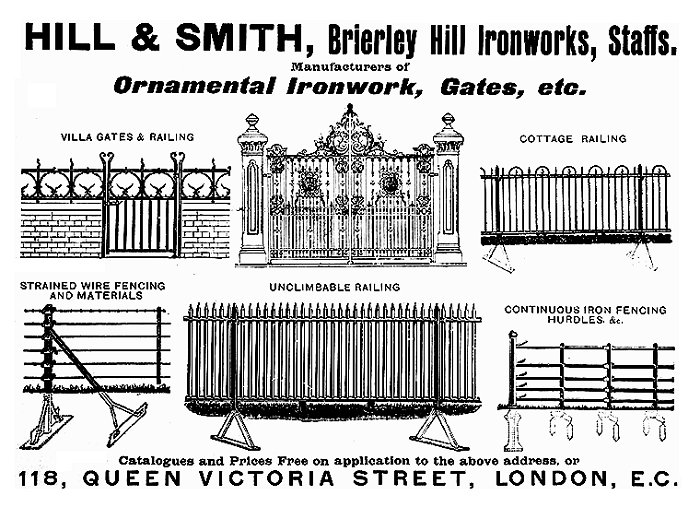

Harts Hill Ironworks

opened in 1836 for the manufacture of hurdles and

fences, mostly for export to the colonies. Edward

Smith ran the ironworks, which by 1851, also

produced wrought iron forgings for steam engines. In

1860 the ironworks manufactured many miles of

continuous fencing for Queen Victoria's estates.

Edward Smith later ran the business with one of his

employees under the name of Hill and Smith. The firm

then manufactured gates and agricultural implements.

By 1883 the firm had around 400 employees.

|

|

Moore and Manby,

ironmasters, Wolverhampton Street, Dudley.

One of the area's high

quality iron makers.

From Griffiths Guide to

the Iron Trade of Great Britain. |

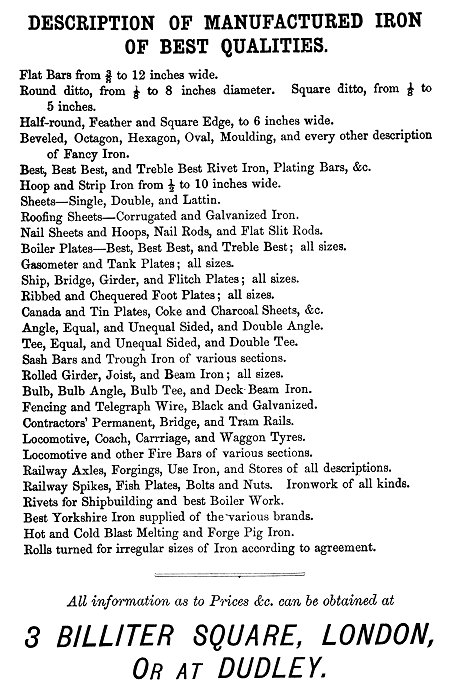

| Moore and Manby,

products. From

Griffiths Guide to the Iron Trade of Great

Britain. |

|

|

Woodside Iron Works was started in 1840

by Alexander Brodie Cochrane and his

son. The firm was also known as Alexander Brodie Cochrane and John

Joseph Bramah. Alexander Brodie Cochrane senior was

born in about 1786 in Eddlestone, Peebles, Scotland.

His son of the same name was born in Dudley

on the 10th February, 1813.

Alexander senior moved to Ironbridge from Scotland

where he went with Lord Dundonald who

developed the tar works there. In about 1830

Alexander senior became manager of Grazebrook’s

colliery and furnaces, near Dudley, where his son,

Alexander junior also worked and learned about iron

production. In 1838 Alexander

Brodie Cochrane junior, went into partnership with

John Joseph Bramah and opened a small iron foundry

in Bilston.

In 1840 Alexander and his son, founded Woodside

Iron Works in partnership with John

Joseph Bramah. They leased land at Woodside next to

the canal and built the ironworks and a foundry

alongside the canal. The partnership was dissolved

in 1842 when Alexander Brodie Cochrane senior,

retired. By 1844 Cochrane and Bramah were

producing around 9,100 tons of iron per year.

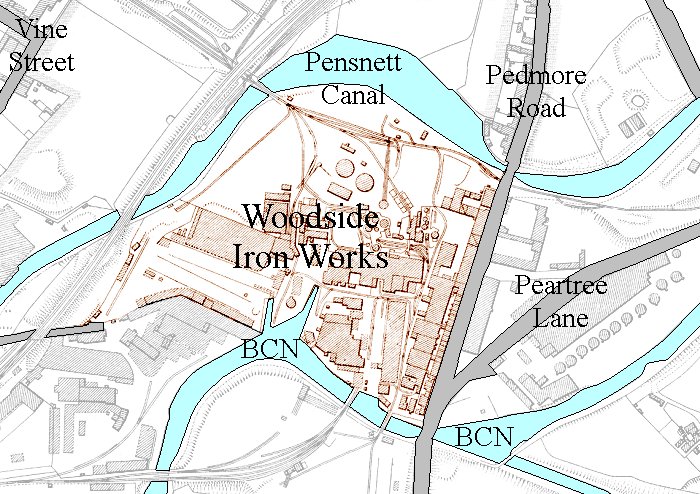

|

|

The location of Woodside

Iron Works. |

|

In 1846 John Joseph Bramah died

and Mr. Charles Geach and Mr. Archibald Slate became

partners. The business then became Cochrane and

Company.

Woodside Iron Works was a great success,

producing large amounts of iron and many products

from the foundry. One of the large orders came from

Fox Henderson of Smethwick, who subcontracted the

work for the manufacture of the huge cast columns

for the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, in readiness for

the Great Exhibition of 1851.

In 1851 Alexander Brodie Cochrane

junior, lived in Kingswinford, with Esther

Cochrane age 40, Mary Cochrane age 12, George

Cochrane age 6, Ellen Cochrane age 3, Donald Alice

Cochrane age 2 and Alfred Cochrane, age 7 Months.

Alexander Brodie Cochrane senior

died on the 8th December, 1853, in Netherton. 1853

had been a time of expansion because the company

acquired several collieries in Northumberland

and Durham, and established the Ormesby Iron Works

at Middlesborough. In 1854 Mr.

Charles Geach died and Mr. Archibald Slate left the

firm. In the same year an order was received

from Australia for 20,000 tons of iron piping for

the Melbourne Waterworks.

In 1855, Alexander Cochrane's

son, Charles, aged 20, went to work at Ormesby

Ironworks and in 1856 became a partner with his

father, both at Woodside and Ormesby. Woodside had

many large orders including ironwork for several

important building projects in London. Including the

large caisson and dock gates for the Victoria docks,

which opened in 1855, ironwork for the new

Westminster Bridge, ironwork for the Charing Cross

Railway bridges, ironwork for Cannon Street Railway

Bridge and railway station and ironwork for the

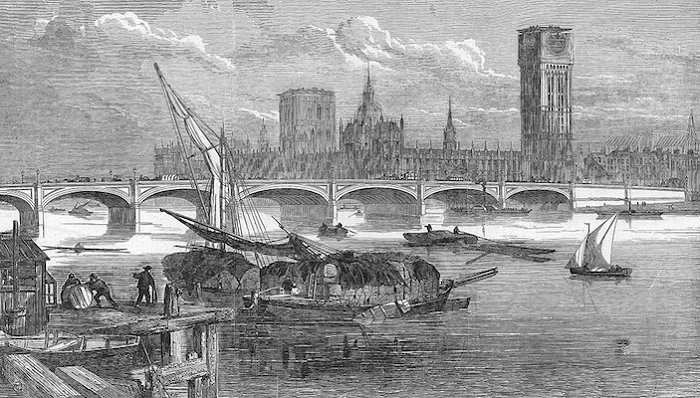

Holborn Viaduct, which opened in 1869. |

|

The New Westminster Bridge.

From the Illustrated London News, 3rd February,

1855. |

|

In 1859 the firm received a large order

for the manufacture of the once-familiar cast

iron pillar boxes, where letters were posted. Sadly, Alexander Brodie Cochrane

died on the 23rd June, 1863, at the age of 50,

after a long and severe illness, at his residence in

Stourbridge. In 1847 he became a member of the

Institution of Mechanical Engineers and for some years

before his death was one of the Vice Presidents. He was

also a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers,

which he joined in 1850 and was a magistrate for the

counties of Worcester and Stafford.

In his later years at Woodside he experimented with

the use of the slack coal for firing ovens and continued

to actively manage the company until several years

before his death, when he became seriously ill. He was

joined by his brother John Cochrane, who devoted much of

his time to the engineering side of the establishment.

Thanks to his efforts, the firm became well known for

the manufacture of cast iron pipes, and supplied nearly

all the principal water and gas companies in the

country, and also many on the continent in the colonies.

In 1868 the firm produced girders for the Runcorn

Bridge over the River Mersey and the Farringdon Street

Viaduct in London. There were many other orders

including ironwork for the Rochester Road Bridge and

Swing Bridge over the River Medway and ironwork for the

Clifton Suspension Bridge.

In 1874 Woodside produced a magnificent wrought iron

bridge for New Street Railway Station in Birmingham.

Charles Cochrane and Joseph Bramah Cochrane took over

the business in 1875 after other family members left. It

was then called Cochrane and Company. In 1890 it became

a limited company.

On the 27th July, 1894, one man was killed and

several were injured as a result of a boiler explosion

on the Woodside site.

Charles and Joseph ran the business until 1896, when

Joseph’s son Walter took over. In 1921 the factory

closed after a strike and was bought by John Cashmore’s

Limited and used to manufacture a number of products

including street lamps. It closed in 1939.

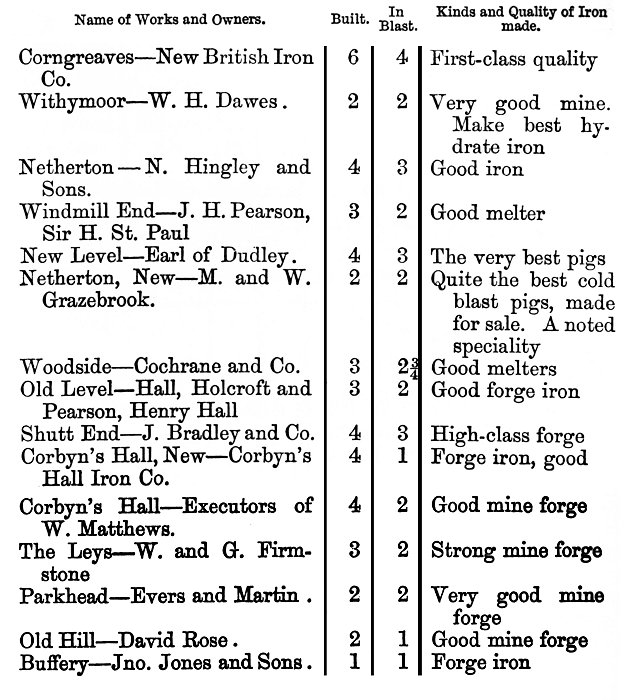

|

|

List of blast furnaces in the

area in 1872. From Griffiths Guide to the Iron Trade

of Great Britain. |

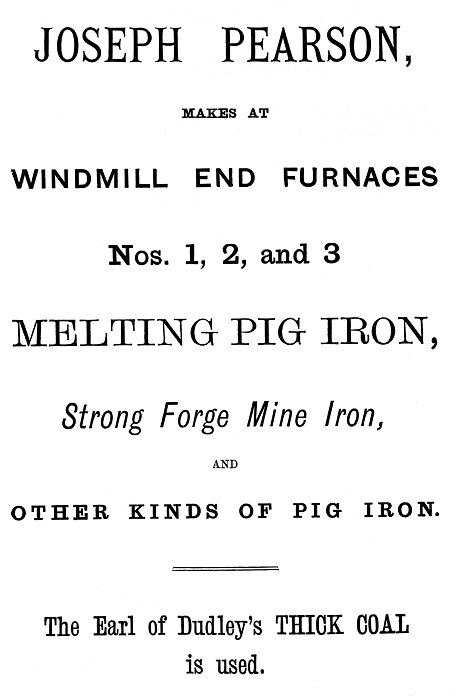

|

From Griffiths Guide to the

Iron Trade of Great Britain. |

|

From Griffiths Guide to the

Iron Trade of Great Britain. |

Hill and Smith was established in 1824 and

became known as Hill's Ironworks. Henry Smith

began working for his brother-in-law, Edward

Hill, which led to a partnership. Henry Smith

died in September 1906 at the age of 82 and was

succeeded by his eldest son, Joseph H. Smith,

who was killed in a carting accident in 1909 at

the of 54. After his death, the firm became Hill

and Smith, a private limited company. Early

products included harrows, cultivators,

chaff-cutting machines, puddling machines,

hurdles, gates and fencing, wrought iron shafts,

crank shafts, piston rods and connecting rods.

Structural steel was also produced for

factories, warehouses, roofs, footbridges and

walkways.

The firm also supplied many miles of fencing

for Queen Victoria in 1860, Ornamental Gates and

parapet railing for the Royal House of Siam,

steelwork for the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the

Royal Dockyard at Simonstown, South Africa,

gates for Hong Kong market and the steelwork for

the dome at Birmingham University.

In 1982 the business became Hill and Smith

Holdings plc. The firm now designs and

manufactures products for the construction and

infrastructure industries. |

|

An advert from 1907. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|