|

Coal Mining

The Earls of Dudley made a massive

fortune from their mineral rights in Dudley and the

surrounding area. At the start of the industrial

revolution, coal and iron ore were in great demand. They

were in plentiful supply in the area and ready to be

exploited. When canals were built, the minerals could be

easily and cheaply transported from the mines to factory

sites.

When the first canal in the

vicinity, the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal

opened, John, second Viscount Dudley and Ward was

largely responsible for linking it to his estates via

the Stourbridge and Dudley canals. He was a shareholder

in four of the canals and introduced three of the Bills

into Parliament that allowed their construction. This

included the Dudley Castle Canal Tunnel that linked the

Dudley and the Birmingham Canals. After the Act was

passed in July 1785, the Dudley Canal Company recorded

its thanks to Lord Dudley for his "Unremitted Attention

to the Interests of the Company and for his very

powerful and successful exertion in Parliament in

support of the Extension of the Canal"

Viscount Dudley and Ward’s estates

in Dudley, Kingswinford, Rowley Regis, Sedgley, and

Tipton contained up to nine seams of coal, including the

rich thick coal or 30ft seam, along with deposits of

iron ore, limestone and clay. The Dudley family became

the leading mine owners in the Black Country, who

greatly intensified the exploitation of their estates.

This resulted in a greatly changed landscape in the area

around Dudley and has led to many cases of subsidence,

which still occur.

|

|

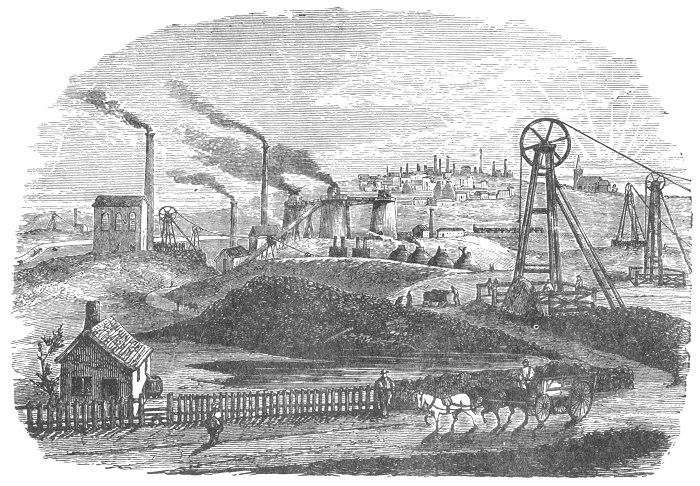

The Earl of Dudley's

coalfields. From Griffiths' Guide to the Iron Trade

of Great Britain. |

|

Lord Ward initially leased the

collieries to charter masters, who employed butty-colliers,

who in-turn employed middle men to employ the

colliers to mine the coal. In 1797 the system was

reorganised when Lord Ward employed Charles

Beaumont, who supervised the colliers himself and

stipulated how the mines would be run. The colliers

were now permanently employed, which didn't happen

with the old system. Every fortnight a minimum

amount of coal had to be brought to the surface.

Beaumont introduced a standard weight for the coal

so that the colliers knew beforehand how much they

would be paid. The standard rates were based on the

types of coal being cut, such as best coal, second

best coal, lump coal and slack.

In the 30 foot seam he started

a new system in which six foot layers had to be cut,

one at a time, to reduce waste. He also instigated

the use of one large shaft instead of two smaller

ones to carry air into the mine, with a stronger

draught. His work resulted in reduced costs and

higher profitability for Lord Ward. In 1803 the

annual profit was over £3,555 which in today’s money

is approximately £355,500.

In 1803 Lord Ward employed

Francis Downing as Mineral Agent for the Dudley

Estate, but by 1826 productivity was falling. So in

1836 he employed Smith and Liddell, mining

engineers, to improve matters. They recommended that

the business should be put in the hands of a mining

engineer and that the mines should be worked to

their full capacity, including the removal of the

thinner seams of coal and ironstone. They also

recommended that the pits should be leased on a 20

percent royalty on sales and that the coal masters

and ironmasters should meet all working costs.

Lord Ward appointed Richard

Smith as Mine Agent to work alongside Francis

Downing. Richard Smith greatly increased the profits

from the mines, which by the end of the century were

producing a lot of coal for domestic use.

In 1841 over a quarter of the

male population of Dudley were occupied in the coal,

iron and limestone mines which were run by 17 coal

masters. Bentley's Directory of 1840 lists that 1.2

million tons of coal and 150,000 tons of limestone

and ironstone were used to produce 24,000 tons of

iron in Dudley parish.

The collieries included the Parkhead and Dudley

Wood Collieries that served Parkhead Furnaces and

Woodside Works, also Shaw's and Badley's at Blowers

Green. At Netherton, the rich supply of easily

obtainable coal from the 30 foot seam contributed

enormously to Dudley's industrial development. It

was free from sulphur and with a characteristic long

flame that was ideal for the iron industry.

Netherton furnaces were well supplied by the New

Bufferies and Bumble Hole Collieries. There were

large coal and ironstone mines at Coneygre,

Russell's Hall, Himley, Knowle Hill and Saltwells.

At

Kates Hill, coal could be found at the surface.

|

|

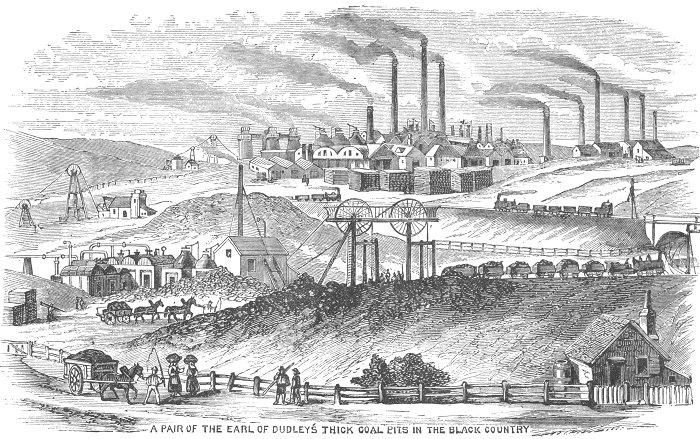

From Griffiths' Guide to

the Iron Trade of Great Britain. |

|

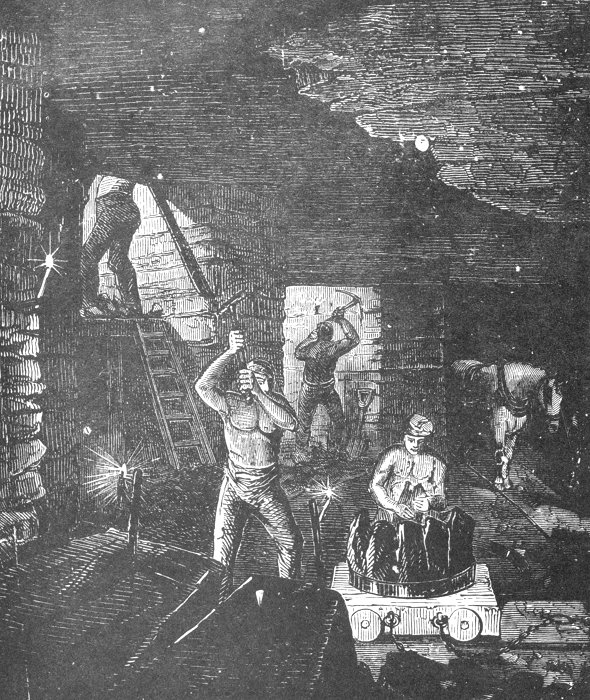

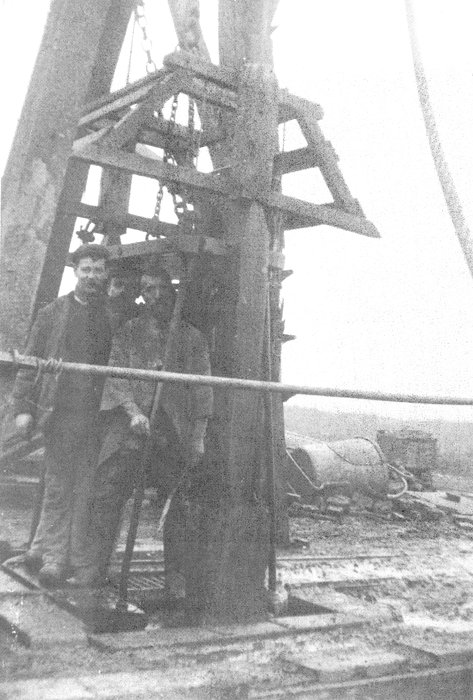

Underground work at

Saltwells Colliery.

From Griffiths' Guide to

the Iron Trade of Great Britain. |

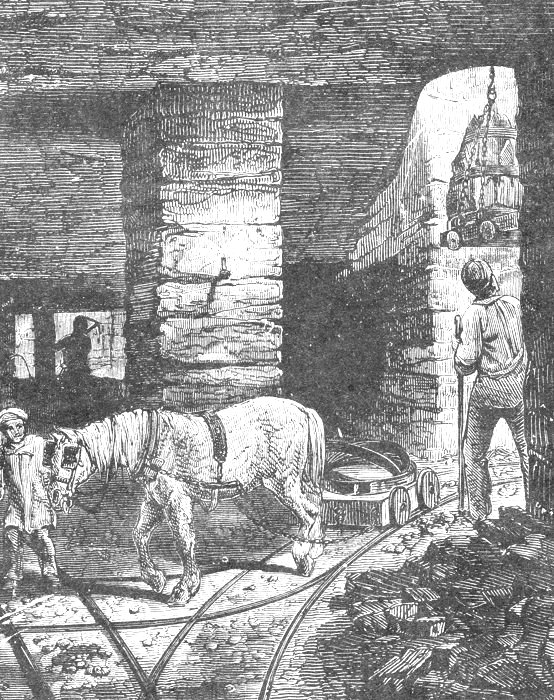

| Getting Coal at one of

the Earl of Dudley's thick coal pits.

From Griffiths' Guide to

the Iron Trade of Great Britain.

|

|

|

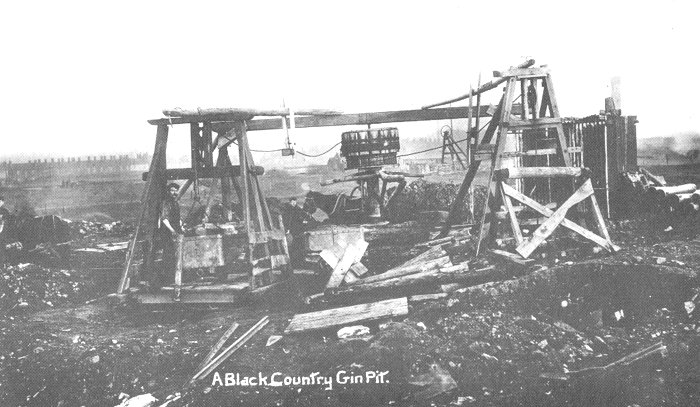

A once common

sight in the Dudley area, a horse-driven

gin pit. From an old postcard. |

|

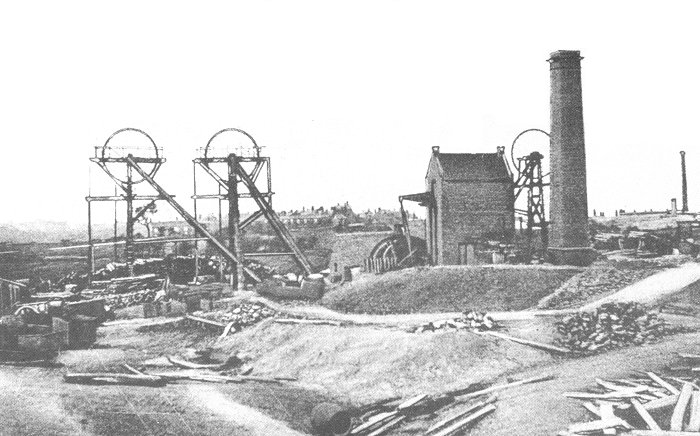

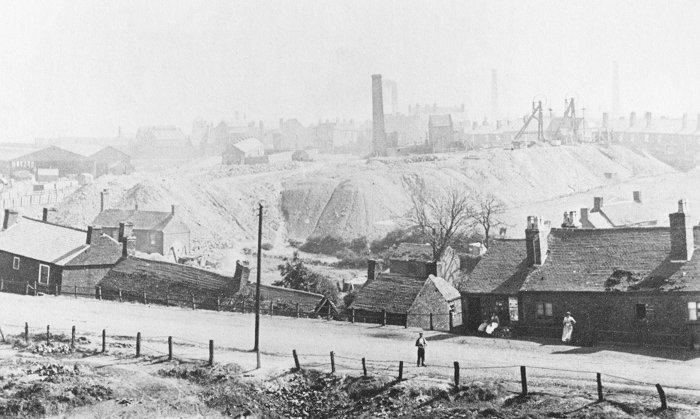

Another

typical view of a coal mining

area with a gin pit in the

foreground. From an old

postcard. |

|

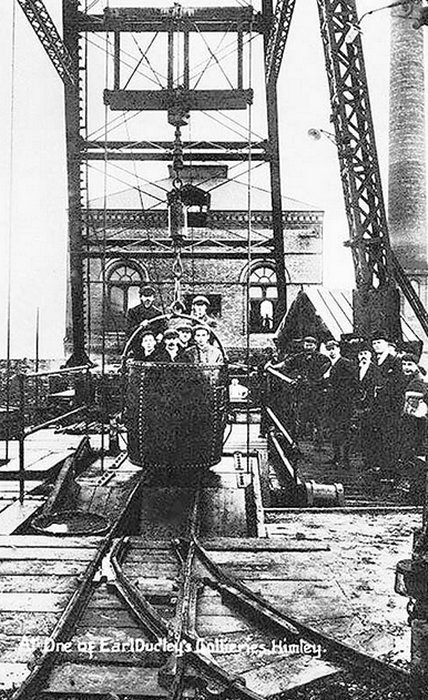

A mine with a

Newcomen steam engine operating a

water pump and the winding gear.

From an old postcard. |

|

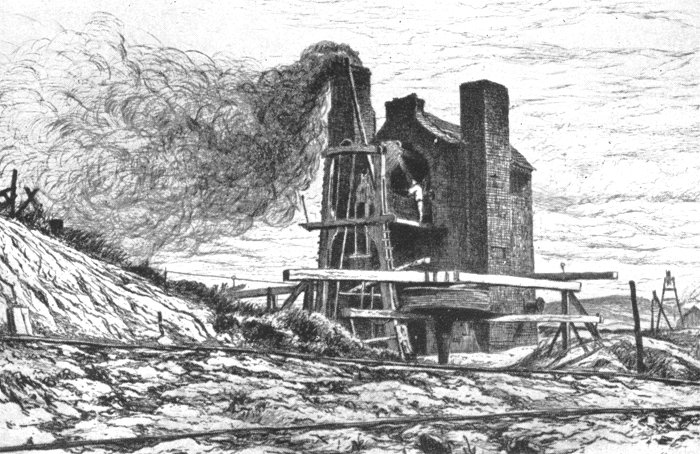

From an old postcard. |

Coal mining was hard and dangerous work. When

the demand for coal was high, miners were well paid,

but when demand fell, their wages were reduced. In

November 1831, many of them joined forces to form a

miners’ union, so wage reductions sometimes led to

strikes and even riots. In 1878 because of the

poverty caused by a wage reduction, a soup kitchen

was opened and 2,200 pints of soup were distributed

in Dudley, in under two hours. Unfortunately wages

continued to fall until the end of the century.

Accidents

There were many accidents including underground

explosions. Two men were killed at Saltwells Colliery when the explosive

firedamp (usually methane) came up from the sump of

the shaft and ignited in 1855.

Firedamp was common

in the Dudley pits, accumulating in pockets in the

coal. It sometimes collected in the underground

workings and could suddenly ignite, killing and

maiming miners. Work in a pit would have to be

stopped at least three times a day so that the gas

could be cleared by firemen who hung a candle from a

long rod and slowly raised it until an explosion

occurred.

|

|

The pumping engine

at the Buffery Pit. From Chandler and

Hannah's 'Dudley as it was'. |

|

In 1808, James Ryan developed a system to safely

ventilate the thick coal at No. 16 Pit, Netherton,

in which passages were cut in the upper parts of the

workings and connected to air pipes running to the

surface. Within a very short time all the firedamp

was removed, which allowed the people underground to

work longer without having to resort to firemen

three times a day. This system was soon used

throughout the country.

|

|

Coal miners leaving a pit

in about 1912. From an old postcard. |

An explosion occurred at Homer Hill Colliery, in

Cradley, owned by Messrs. Evers and Sons, on the 1st

November, 1866. The explosion occurred underground,

killing twelve men. On the 26th April, 1853, eleven men died in an explosion

at Old Park Colliery, Dudley, owned by Lord Ward, and another nine men died in

September 1857 at an explosion in Gwane Colliery,

Rowley Regis, owned by William Mills and Son.

The risk of an explosion could

be reduced by the use of a Davy lamp, which was

introduced into the Black Country in the early 19th

century.

It was not liked in

Dudley because the lamps did not give enough light

and the gauze which made the lamps safe, would

clog-up with coal dust, so that the miners could

hardly see what they were doing.

Men also died in accidents

while being lowered or raised from the pit. On the

20th June, 1856, eight men fell to their deaths

while being lowered down the shaft at number 20 pit,

Old Park Colliery, Dudley, when a chain broke.

|

|

Dangerous working

conditions at the coal face. From an old

postcard. |

|

Mining subsidence in

Northfield Road, Netherton. From an old

postcard. |

|

Mining subsidence in

Scotts Green Road on 13th November, 1922. From

an old postcard. |

|

At Bridge End Colliery in Pensnett, run by Mr. Raybould,

six men were killed on the 11th. January, 1864 when

a pit horse fell down the shaft onto the men who

were being lowered into the mine. At Woodside

Colliery in 1893, three men were killed when the

winding machine broke while bringing them to the

surface.

At number 10 pit, at Saltwells on the 9th. February, 1865, around fifty

tons of coal fell around seventeen feet at one of

the openings, killing six men. On the 18th.

March, 1929 at Coombs Wood Colliery, in Halesowen,

managed by Mr. H. J. Newey, eight men died after an

underground fire. In another underground fire at the Old Buffery Colliery in

1875, four men died.

|

|

Coalmines in Dudley

in 1896: |

|

Colliery |

Manager |

Minerals |

People Underground |

Surface

Workers |

|

Bournehills, Netherton. |

J. Williams |

Coal, Ironstone |

76 |

28 |

| Brettell Lane, Brierley Hill. |

George King Harrison |

Coal, Fireclay |

13 |

3 |

| Bridge End, Brierley Hill. |

J. W. Grocott |

Coal |

51 |

11 |

| Brickhouse, Rowley Regis. |

G. H. Dunn |

Coal |

37 |

8 |

| Brockmoor, Brierley Hill. |

R. Mills & Company |

Coal, Ironstone |

44 |

17 |

| Bromley, Brierley Hill. |

J. W. Growcott |

Coal, Ironstone |

57 |

20 |

| Bromley Lane, Pensnett. |

J. A.

Fullwood |

Coal |

83 |

17 |

| Coneygre, Rowley Regis. |

H. W. Hughes |

Coal, Ironstone |

301 |

111 |

| Corbyns Hall, Kingswinford. |

Bennett & Bradley |

Coal |

10 |

7 |

| Delph, Brierley Hill. |

Hickman & Company |

Coal, Fireclay |

9 |

4 |

| Fly, Old Hill. |

W. B. Keen |

Coal |

21 |

6 |

| Granville, Old Hill. |

W. B. Collis |

Coal |

|

|

| Knowle, Rowley Regis. |

R. Mason |

Coal, Ironstone |

80 |

25 |

| Merry Hill, Brierley Hill. |

Firebrick Works, Stourbridge |

Coal |

11 |

3 |

| Oak Farm, Dudley. |

J. Walker |

Coal, Fireclay |

12 |

4 |

| Old Hill, Old Hill. |

Noah Hingley & Sons |

Coal, Ironstone |

133 |

51 |

| Pearson, Old Hill, |

H. Johnson |

Coal |

22 |

14 |

| Saltwell, Cradley. |

C. F. E. Griffiths |

Coal, Ironstone |

167 |

59 |

| Scotwell, Rowley Regis. |

Hawes Hill Colliery Co. |

Coal |

10 |

4 |

| Shut End, Kingswinford. |

D. Rogers |

Coal, Ironstone |

113 |

67 |

| Stour, Cradley Heath. |

David Parsons |

|

45 |

27 |

| Stourbridge Extension,

Kingswinford. |

Himley Firebrick Company |

Coal, Fireclay |

15 |

6 |

| Straits Green, Lower Gornal. |

J. W. Newey |

Coal, Ironstone |

26 |

7 |

| Thorns, Brierley Hill. |

Gilbert Claughton |

Coal, Fireclay |

18 |

18 |

| Tiled House, Kingswinford. |

R. S. Dodd |

Coal |

86 |

32 |

| Timbertree, Cradley Heath. |

W. H. Chapman |

Coal |

40 |

25 |

| Turners Lane, Brierley Hill. |

Harris & Pearson |

Coal |

15 |

9 |

| Upper Gornal, Dudley. |

A. P. Taft |

Coal, Fireclay |

32 |

5 |

|

|

Salop Street No. 2

Fireclay Pit in the London Fields area. From an

old postcard. |

|

Fireclay

Mines in Dudley in 1896: |

|

Mine |

Manager |

Minerals

|

People

Underground |

Surface

Workers |

| Brettell Lane, Brierley

hill. |

Trotter, Haines &

Corbett |

Fireclay |

14 |

5 |

| Clattershall, Brettell

Lane, Stourbridge. |

Bowens Limited |

Fireclay |

15 |

4 |

| Crown, Amblecote. |

E. J. & J. Pearson |

Fireclay |

15 |

2 |

| Dibdale, Lower Gornal. |

T. E. Jackson |

Fireclay, Pyrites |

38 |

15 |

| Freehold, Lye. |

William Cox |

Fireclay |

3 |

1 |

| Moor Lane, Brierley

Hill. |

John Hall & Company |

Fireclay |

17 |

9 |

|

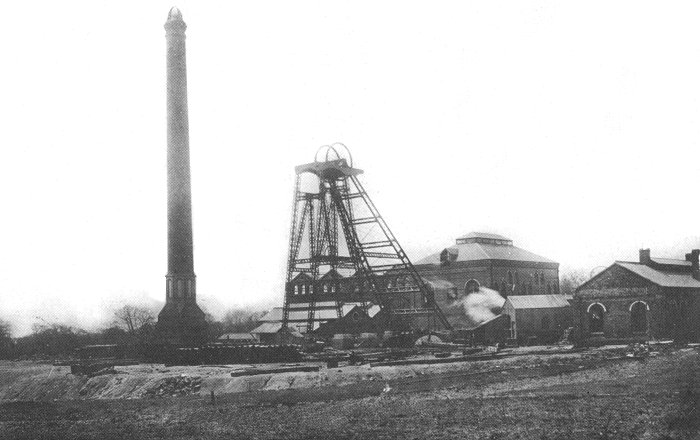

| The Dudley family’s last pit, Baggeridge Colliery,

began life after the first shaft was sunk in 1902 to

reach a thick coal seam, 1,800 feet below the

surface. Two further pit shafts were sunk in 1910

and full production began in 1912. It was served by

a branch of the Earl of Dudley's Pensnett Railway

and in its heyday employed 3,000 men who produced

around 12,000 tons of coal per week. The pit closed

on the 2nd March, 1968 and was the last remaining

pit in the Black Country. |

|

Baggeridge Colliery. From an

old postcard. |

|

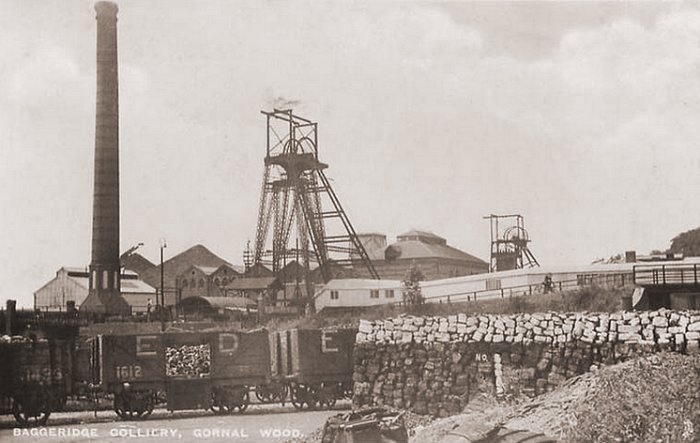

Another view of Baggeridge Colliery. From an

old postcard. |

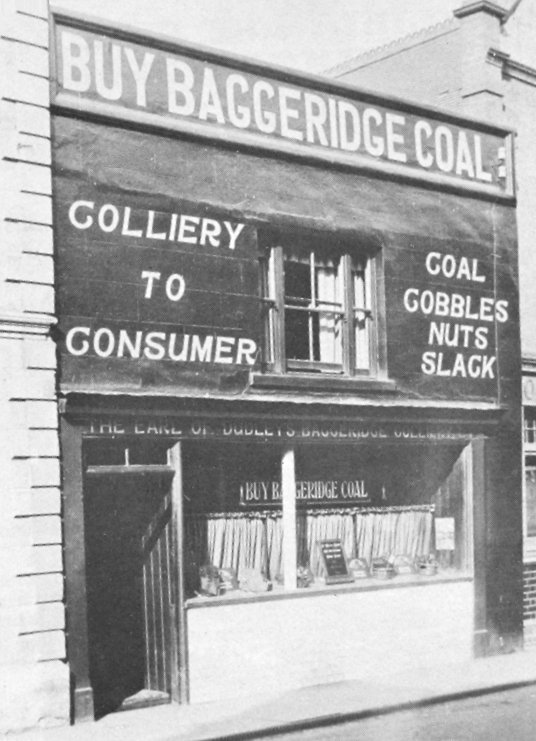

One of the many

Baggeridge Colliery shops that sold coal

directly to members of the public. |

|

An advert from 1958. |

| Limestone Mines From the end of the 18th century, limestone was

in great demand due to the opening of many ironworks

and the ease of transportation on the newly built

canals. It was used as a flux that was essential to

iron making. Silurian limestone, outcrops in a series

of faults in the Dudley area that form Castle Hill,

Wrens Nest Hill and Hurst Hill.

|

Limepit Lane that ran

alongside Wrens Nest Hill, as seen in the

1920s. In the distance is the chimney and

pithead gear of one of the limestone mines. |

| The limestone

outcrops were mined for hundreds of years, initially

for building stone and mortar, then with the coming

of iron making, it was in great demand for use as a flux. During the

height of the industrial revolution, up to 20,000

tons of local limestone was quarried annually. It

was laid down in a shallow sea and was known for its

wide variety of fossils including large numbers of

trilobites. Because they were so common, they became known as the ‘Dudley Bug’. |

|

Wrens Nest, from where

most of the good quality limestone was quarried. |

|

Wrens Nest in the mid

1970s. |

|

A trilobyte. |

| The first part of Lord Ward’s canal tunnel was

built to help transport the limestone that was

extracted from the mines inside Castle Hill, through

which the tunnel runs.

A branch from the main tunnel

that runs to Parkhead, went under Wren's Nest to two

underground basins, east basin and west basin, to

transport limestone from the underground workings.

This is now blocked off.

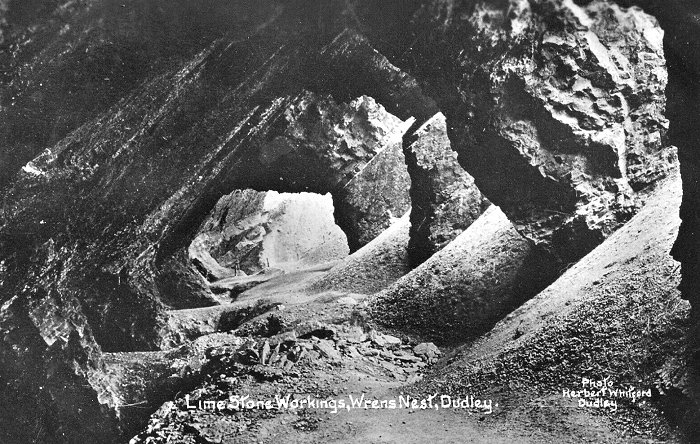

Wrens Nest was well known for its large surface

cavern known as the ‘Seven Sisters’ which is more

than 100 metres long.

Quarrying ended in 1925 and

the site was abandoned. In 1956 it became a national

nature reserve.

In 2004, Wren's Nest and the nearby

Castle Hill were declared Scheduled Ancient

Monuments, because they represented the best

surviving remains of the limestone industry in the

area.

The Seven Sisters Cavern had to be filled in

with loose sand after a major roof collapse in 2001. |

Seven Sisters Cavern. From

an old postcard. |

|

The Seven Sisters

Cavern. From an old postcard. |

|

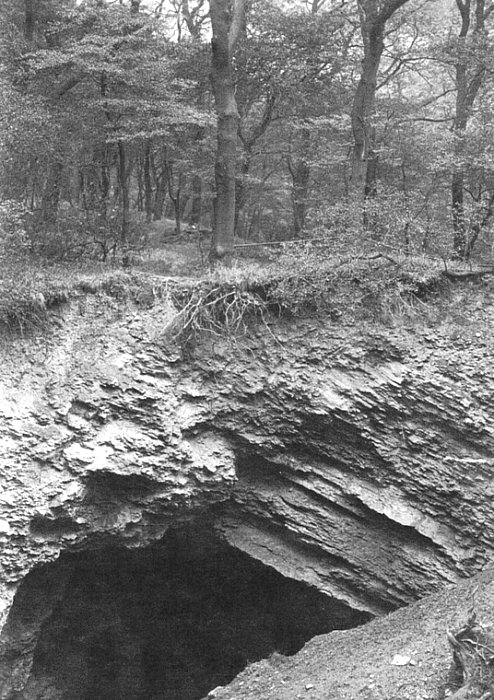

Old limestone

workings on Castle Hill. From an old

postcard. |

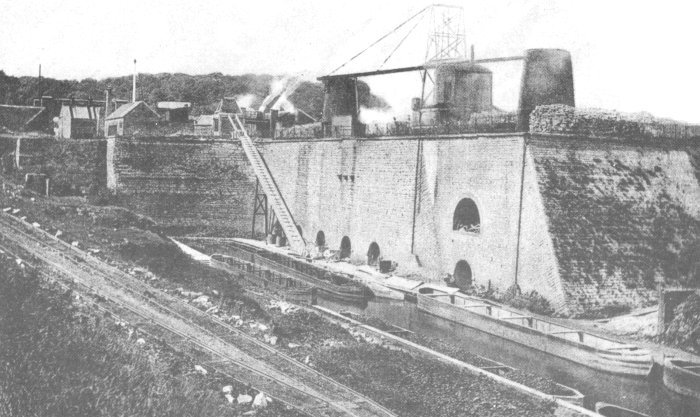

Visitors to the Black Country Living Museum can

see the remains of lime kilns beside the canal. A

reminder of the once-important limestone industry.

From an old postcard. |

|

Another view of the lime

kilns at the Black Country Living Museum. From

an old postcard. |

|

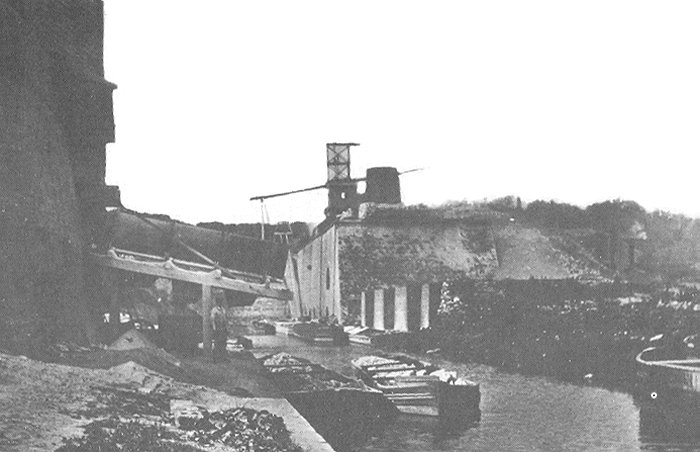

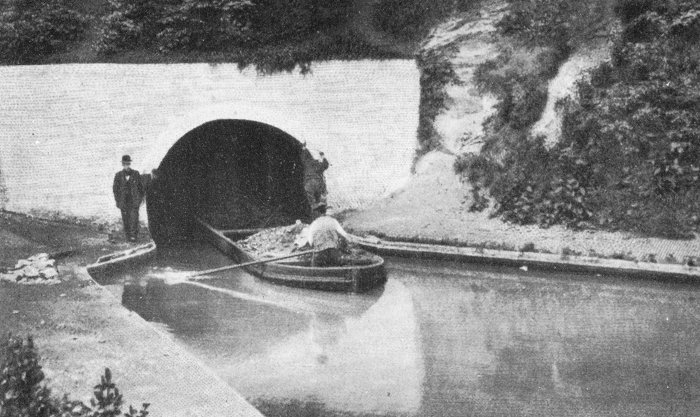

A canal boat leaving the

Dudley tunnel. From an old postcard. |

|

A boat full of

tourists entering the canal tunnel in modern

times. |

|

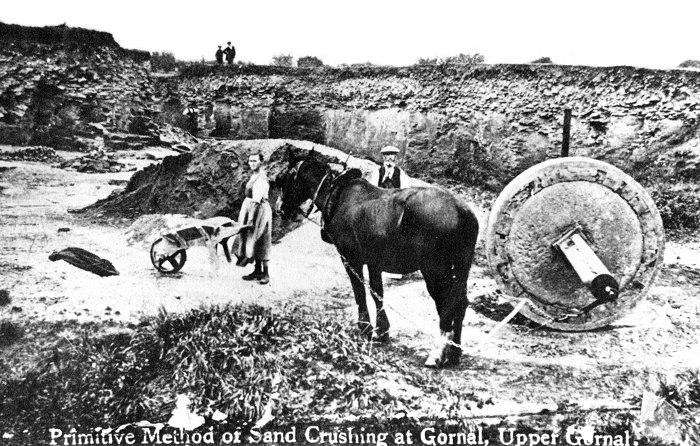

Clay has also been extensively mined in the area, for use in

brick making and for industrial furnaces. Vast clay

deposits have been found all around Dudley, where a large

number of fireclay mines and brick and tile works

formed part of the local landscape. |

|

Local

sand deposits were well-worked for glass-making. From an old

postcard. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|