|

The Priory of St. James

The priory was founded by

Gervase Paganel, whose father Ralph Paganel had intended

to establish a religious community in Dudley. The priory

was Gervase’s own private church, little more than a

burial place for his family, which also acted as a

guesthouse for the castle. The Cluniac priory of Dudley

was founded in about 1160 with just three or four monks

and Osbert the first prior. It was part of a Benedictine

order, founded at Cluny in eastern France in 910.

When founded it had little

influence in the area and was just an appendage of the

castle. It was also dependent on the priory at Much Wenlock. The

priory was largely supported by income from a number of

parish churches, as well as from the two half hides of

land that it owned, and various rights of pasture. The

castle estates provided a tithe of bread, venison and

fish, as well as rights to take wood for building and

other needs. The priory was surrounded on at least three

sides by large fishponds and mill pools. The monks seem

for the most part to have led a quiet uneventful life

under the protection of the Paganel family.

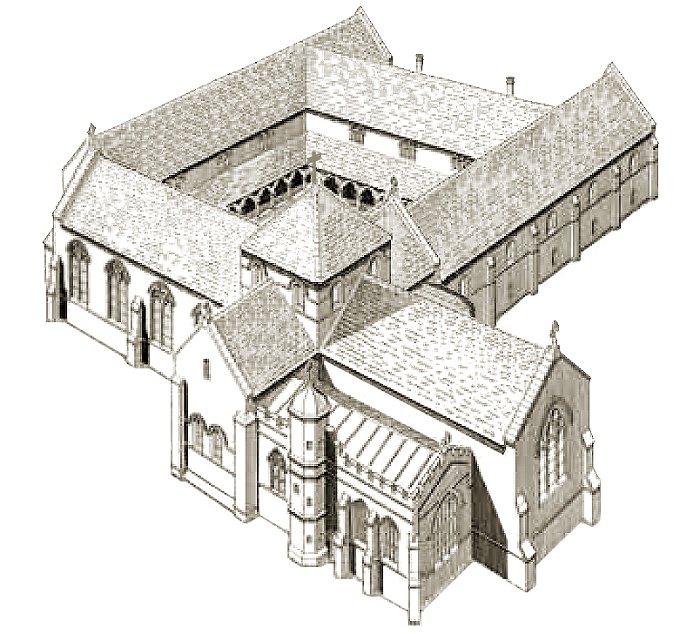

The priory was cruciform

with an aisleless nave and two chapels on the south side

of the choir, the eastern chapel being separated by a

blank wall from the western chapel, which opened

directly out of the south transept. Gervase Paganel

appears to have built only the crossing with the

transepts, each with a small apse and a very plain east

cloister building, with a chapter house and day room

below, and a dormitory and a toilet. The east end was

erected in about 1190 and the nave was probably built in

the early 13th century.

The cloister and monastic

buildings were to the north of the church, rather than

the usual position to the south. In the north east

corner of the north transept are remains of a newel

staircase that ran between the dormitory and the church

and also traces of four central arches. The stonework is very plain, but of

good standard. During the late 14th century, John

Sutton, Lord of Dudley bequeathed 20 pounds for his

burial within a grand tomb, and a very fine stone

vaulted chapel of three bays was built on the south side

of the choir. |

|

Based on the image on the public

information panels, beside The Broadway and Paganel Drive.

|

|

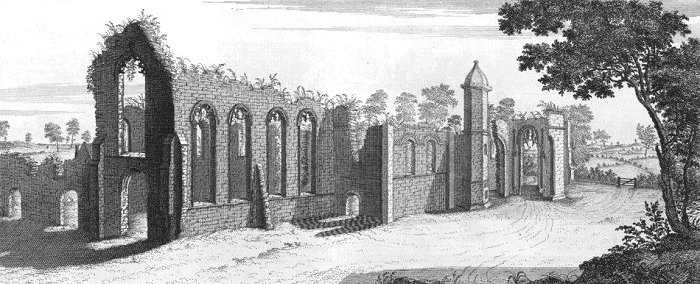

An engraving of the priory

before industrialisation. From an engraving by S. &

N. Buck, 1731. |

|

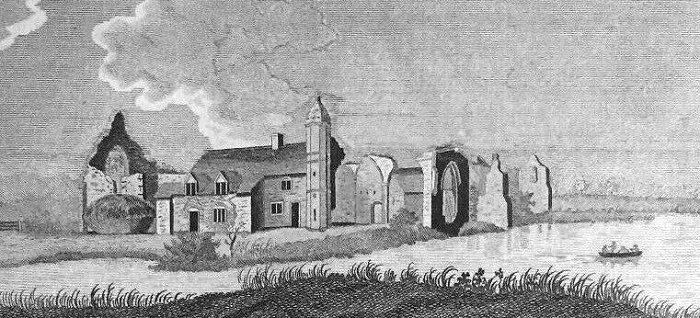

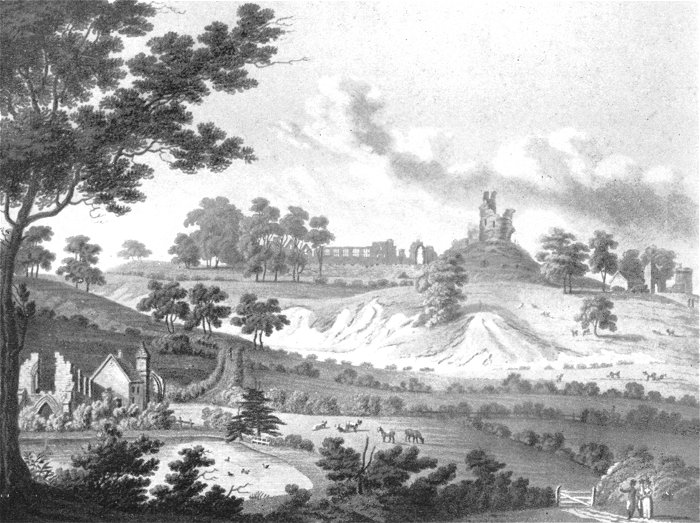

A view from the

1770s. |

|

The prior of Dudley,

like others from Cluniac monasteries, was probably

suspected or implicated in the rebellion of Thomas,

Earl of Lancaster, in 1322. He was arrested by order of the king and then released in October,

1323.

The population of the priory is never thought to

have exceeded around five monks and a prior. When it

was dissolved in the 1530s it was valued at 36

pounds and 8 shillings. In 1545 the estate was

granted to Sir John Dudley, and the church and

buildings fell into decay.

Although Dudley’s ruling families did not possess

a water mill in the 16th century, the priors of

Dudley had one in their possession, which had been

taken over by Lord Dudley in around 1610. In the 1640s

the priory was used to store ammunition during the

Civil War.

| The site was later used

for various industrial purposes, including a

tannery, a water mill and an iron works. A large kiln

was also inserted in the western range

during the industrial period. A tanner built

a cottage in the ruins in the 1770s, using one of

the walls and some dressed stones from

the site.

By 1776 a

thread manufacturer also occupied the site and a

steam mill was built there, possibly in

the area once occupied by the cloisters.

In 1801 the mill was using ground glass

to polish items made from steel,

including fire irons. |

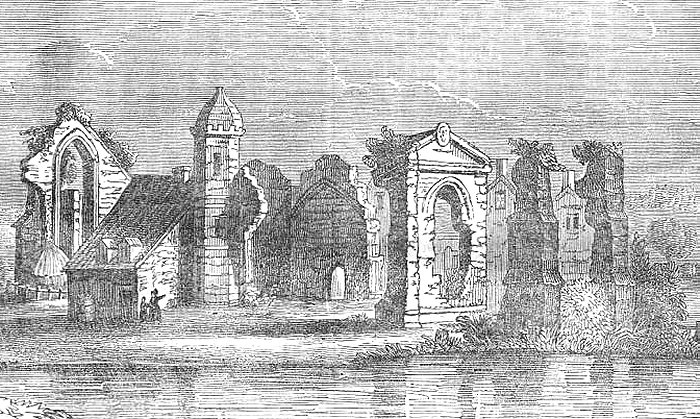

A drawing from the

1880s showing the steam mill and the

other industrial additions. |

In 1825 the Earl of

Dudley constructed Priory Hall on the north western

side of the priory ruins as a family residence. The

ruins were then incorporated into the grounds of the

new house and the industrial additions including the

cottage were removed. The site was cleaned-up, the

walls were planted with ivy and the remains of the

medieval fishponds were drained. The grand drive

from The Broadway to the house was then constructed

through the park-like grounds.

The ruins include some

spectacular arches. The outlines of the monastic

buildings and cloisters are marked in the

grass by stones, put there by the

archaeologist, Rayleigh Radford, in 1939. The

remains of the priory are now Grade 1 Listed.

The Priors were as

follows:

Osbert, circa 1160.

Everad, circa 1182.

William.

Robert de Mallega, recorded in 1292 and 1298.

Thomas de Londiniis, recorded in 1338 and 1346.

William, recorded in 1351 to 1352 and 1354.

Richard de Stafford, circa 1400.

John Billingburgh, who died in 1421.

William Canke, appointed in 1421 and resigned in the

same year.

John Brugge, appointed in 1421, recorded in 1434.

John Webley, circa 1535.

Thomas Shrewsbury, who received a pension in 1539 to

1540. |

|

|

|

Another view from the

1770s. |

|

A view from the eastern end of

the site in the

1770s. |

|

The industrialised site. |

|

From the Saturday Magazine, December 1839. |

|

From an old postcard. |

|

The priory and the

castle in 1831. From an engraving by H. F.

James. |

|

Gardeners at work

in the early 1900s. From an old

postcard. |

|

The main entrance. |

|

The main entrance

and the nave. |

|

Inside the

nave looking towards the entrance. |

|

The

Priory, seen from The Broadway. |

|

The internal arch at the end

of the nave. |

|

The eastern end of the

site. |

|

The monastic buildings

and cloisters as marked out, and the remains

of a staircase. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|