|

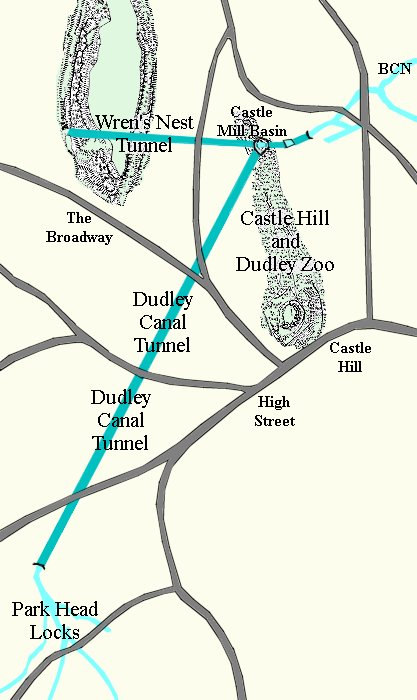

An Act of Parliament allowing the

construction of the canal and tunnel, linking the Dudley

Canal with the Birmingham Canal, was passed on the 4th

July, 1785. Work quickly started on the project, under

the supervision of John Pinkerton and Adam Lees, who was

chief engineer. They were assisted by Thomas Dadford.

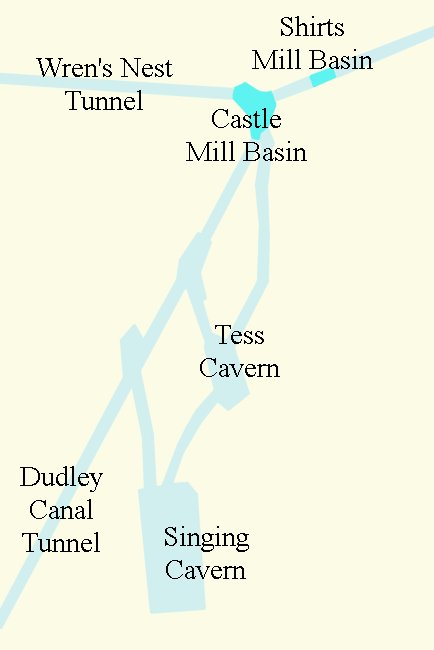

The tunnel, which is 3,172 yards

long was built with a minimum headroom of 5 feet 9 inches and a width at the

waterline of 8 feet 5 inches. There are two open basins

towards the northern end of the tunnel, Shirts Mill

Basin and Castle Mill Basin. The building work included

the construction of five locks at Park Head, which

raised the canal from its old level to the level of the tunnel and the Birmingham

Canal.

The work at Park Head was carried out by Brown

and Green, a local building firm. John Pinkerton

resigned from the project and Brown and Green agreed to

carry out the remaining work on the tunnel. In 1789 it

was discovered that errors had been made in the original

survey, which made the construction more difficult.

Sadly Brown and Green had financial difficulties and

were declared bankrupt, so the tunnel had to be

completed by local labour, recruited by the company’s

engineers.

In January 1792, the working shafts

not needed for ventilation were closed and in February

the tunnel was open for navigation. The final work on a

shortened link to the Birmingham Canal was completed in

March, 1792. The Birmingham Canal Company insisted on

building a stop lock at Tipton Green because of fears of

losing water to the Dudley Canal. The tunnel opened for business on

the 15th October, 1792. The canal now took a lot of

traffic from the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal,

offering a faster route to Birmingham. |

|

Initially limestone was quarried

from the immediate area near the tunnel, but as more of

it was used, work began on the Wren’s Nest Tunnel that

linked Castle Mill Basin to the limestone mines at

Wren’s Nest. It was over half a mile long and was linked

to the mines by many tramways and foot tunnels.

Limestone was blasted from the roof and sides of the

mines in pieces weighing as much as 100 tons, which

would fall to the bottom and break-up into smaller

pieces. The limestone was then loaded onto tramway

wagons and taken to the canal to be loaded onto boats,

which were about 30 feet long by 5 feet 6 inches wide

and could carry about 10 tons of stone.

The boatmen

propelled the boats using long poles pushed against the

tunnel roof, or where space allowed, they would be

"legged" by boatmen lying on their backs and walking

along the sides or roof of the tunnel with their feet.

By the middle of the 19th century,

most of the limestone near the main tunnel was worked

out and so mining became concentrated on Wren's Nest

Hill.

As built, the main tunnel was unlined, but due to

pieces of rock falling from the roof, a brick lining

was added in 1816, except in areas where there was

rock movement due to the many faults in the area. |

|

| In 1836, stop gates were built at the tunnel ends to

protect boats in the tunnel from accidental loss of

water. In 1845, the Dudley Canal Company was

amalgamated with the Birmingham Canal Company and

the stop lock at the junction of the two canals was

removed. In the mid 19th century the tunnel

was extremely busy. Over 100 boats per day used the

tunnel, carrying coal, limestone, iron ore, timber, clay

and items manufactured in the local factories. Because boats could

not pass each other in the narrow tunnel, a timetable

had to be drawn up and boats went through in convoys

from each end, at certain times. |

|

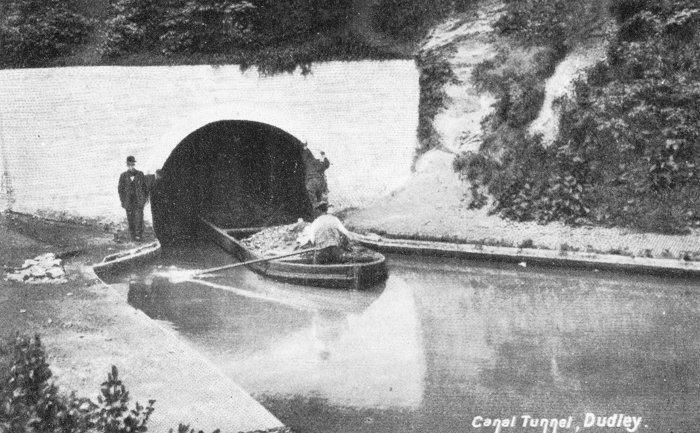

A narrow boat leaving the

Dudley Tunnel. From a postcard posted in 1908. |

|

Part of the main tunnel. |

|

In 1858 the Netherton Tunnel opened

with a tow path on either side of the canal so that

boats pulled by horses could go through the tunnel and pass one another. Both tunnels continued to

be heavily used until the later part of the 19th century

when railways began to take trade from the canals. At

this time more of the remaining traffic used the Netherton Tunnel in preference to the narrow Dudley

Tunnel, which had to be rebuilt at the southern end in

1884, due to mining subsidence.

By the 1930s, road transport began

to greatly reduce canal transport and by the early

1950s, less than half a dozen boats passed through the

Dudley Tunnel each week. The numbers rapidly fell and in

1959 British Waterways decided that the tunnel should

close. A protest cruise was held in October 1960, but

in spite of strong protests from canal societies, the

tunnel was officially abandoned by British Waterways in

1962.

|

|

Castle Mill Basin. |

On the 1st January, 1964, a group

of canal enthusiasts formed the Dudley Canal Tunnel

Preservation Society, which soon had several hundred

members.

The society organised trips through the tunnel

and gave talks to other societies and organisations,

also managing to publicise their campaign on radio and

TV. They were eventually acknowledged by British

Waterways and in 1970 became the Dudley Canal Trust.

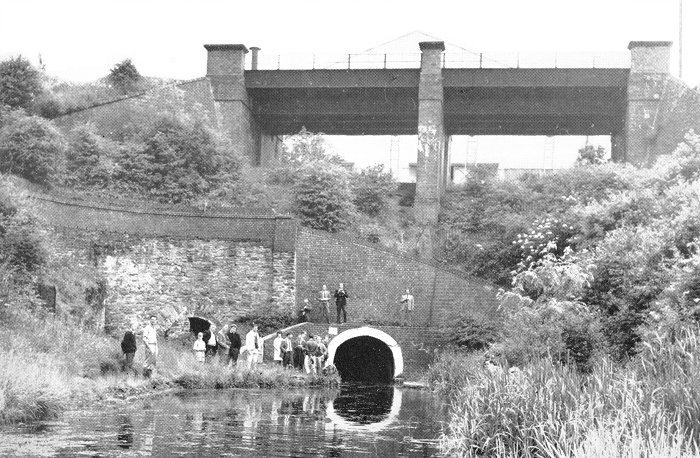

In 1968, the railway bridge that

passed over the northern end of the tunnel was declared

unsafe and so British Railways decided that it should be

replaced by an embankment that would completely cover

the tunnel.

By the late 1960s, the railway was largely

used for goods and in 1968 it became a victim of the Beeching cuts. It was completely closed and so the

embankment was never built.

People’s attitudes to the canals

were changing and in 1968 the government announced that the

membership of the Inland Waterways Amenity Advisory

Committee (IWAAC), would include members from the Inland

Waterways Association, which campaigned for the

conservation and restoration of the British canal

network. |

|

Many volunteers became involved in the project to

restore the canal and the tunnel to their former glory.

Dudley Corporation became the first local authority to

finance canal restoration, announcing that they would

fund half of the repair costs for the tunnel branch, as

well as landscaping the derelict land at Park Head,

around the southern end of the tunnel. Thanks to help

from British Waterways and Dudley Borough Council,

around 50,000 tons of mud and debris were dredged from

both ends of the tunnel and the locks to the south were

restored.

At Easter 1973, the tunnel was reopened and around

300 boats and 14,000 visitors came to the event. The

trust began running boat trips into the tunnel and a

boat was converted to use a battery-powered electric

motor in 1975. By August 1977, the Dudley Canal Trust

had carried around 25,000 visitors through the tunnel,

but subsidence near the southern end led to its closure in

1979. It took many years to find sufficient funds for

the repairs. Grants from several organisations including

the European Regional Development Fund, totalling around

three quarters of a million pounds, enabled the brick

lining to be removed from a section, 110 yards long and

replaced with a concrete tube. The tunnel reopened in

1992.

|

|

Part of the southern end

of the tunnel. |

|

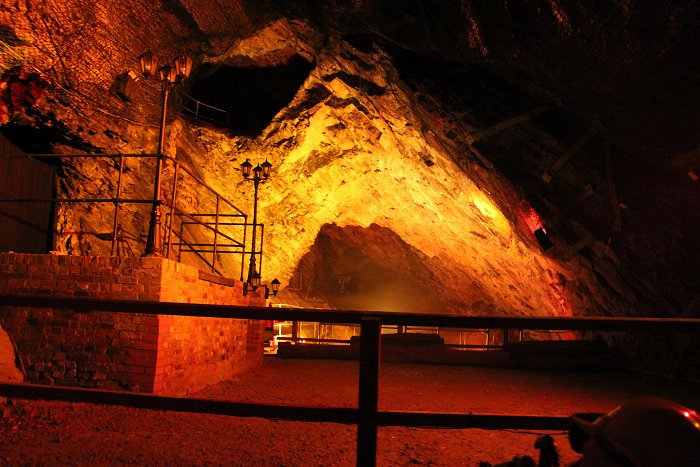

Some of the limestone workings

beside the canal in the Dudley Tunnel. |

|

The northern end of the

tunnel. |

| In 1984 a new tunnel was built to provide access to

the Singing Cavern, which was formally opened on the

23rd April, 1985, by Neil MacFarlane and John Wilson. By

1987, work began on an extension

between the Singing Cavern and the Little Tess cavern.

The work involved the excavation of part of the blocked

rock tunnel, along with a new tunnel to link Little Tess

Cavern to Castle Mill Basin. The new route was formally

opened by councillor D. H. Sparkes, on the 25 April,

1990.

In 1996 the trust took-over the disused Blowers Green

Pumphouse and converted it into offices, an education

centre, workshops and stores. It is now used for social

functions and storage.

The tunnel became extremely

popular. By 2004 between 80,000 and 90,000 people were

visiting the attraction each year.

On the 4th March,

2016, the Trust’s new headquarters, the Portal Building,

was formally opened by Princess Anne and the attraction

continues to go from success to success.

|

|

|

Return to the

previous page |

|