| Introduction

In the 13th century Wolverhampton became a prosperous market

town catering for the surrounding area. A market has been in

existence in the town since before 1204 when the market day was

moved from Sunday to Wednesday. In 1258 King Henry III granted

the town the right to hold the weekly market on every Wednesday.

Good roads would have been an essential requirement for the

development of the market town and Wolverhampton must have

developed many links with the Welsh border country to the west,

which was home to some of the best sheep in the country. Over

the next century Wolverhampton's fortunes continued to improve

and the town became wealthy from the wool trade. Wool was

purchased by the local wool merchants and sold on to Europe

where it was used by clothing manufacturers.

|

|

Read about the local wool

trade |

The Great Hall as shown on Taylor's map of

1750. |

Wolverhampton had a number of successful wool

merchants, the most prominent and influential of which was the

Leveson family (pronounced Leweson). In the late 16th or early

17th century the family built a grand moated mansion house,

complete with gardens and an orchard. The house was originally

called 'The Great Hall' and later became known as 'The Old

Hall'.

A recent excavation at the Old Hall Street Adult Education

Centre has uncovered some of what remains of the north western

corner of the hall and moat. The excavation was carried out by

Birmingham University's Field Archaeology Unit and a lot of

interesting discoveries were made. This important excavation has

given us a unique opportunity to investigate Wolverhampton's

medieval past. The following description has kindly been written

for us by Mike Shaw, Black Country Archaeologist. |

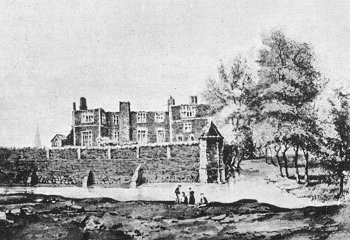

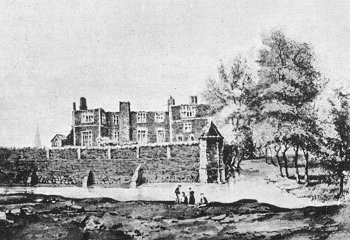

| A drawing showing the Old

Hall and moat. From a 1907 edition of the Wolverhampton Journal. |

|

| Archaeological

excavations at the Old Hall, Wolverhampton

Excavations in Wolverhampton have uncovered the remains of

the Old Hall, one of the principal buildings of the

medieval/early post-medieval town. The Old Hall was built by the

Leveson family who were wool merchants and one of the most

prominent and influential families in Wolverhampton. It is shown

on the earliest map of Wolverhampton (Taylor's map of 1750) as a

large mansion house with gardens and orchards, surrounded by a

moat.

The work was carried out between October and December 2002 by

Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit and represents the

culmination of a process of documentary research and trial

excavation designed to locate the precise position of the hall.

The present excavations located a section of the moat of the

hall which proved to be around 10m (30 feet) wide and 3m (10

feet deep). Within this were located the curtain wall around the

moat and the foundations of a wing of the hall itself. The

foundations were of stone, around 1.4m (4 feet wide) but we know

from later drawings that the hall was a three-storey brick

structure. There may, however, have been an earlier building on

the site as John Leland in his itinerary, written in the 1530s,

refers to the ancient house of the Leveson family on the edge of

Wolverhampton.

The hall remained in the hands of the Leveson family through

the 16th and 17th centuries but by the 18th century was in the

hands of Joseph Turton, a local ironmaster. Contemporary maps

show that the ditch had been filled in by 1842 but the hall

itself survived until 1883 when it was demolished. Prior to this

it was in the hands of William and Obediah Ryton who turned much

of the hall into a japanning factory. |

|

The location of the excavation site.

|

The excavations recovered a wide range of artefacts,

especially from the fill of the moat ditch. These include pottery

tablewares, glass bottles and even a silver spoon. Preliminary

analysis suggests a 16th to 18th century date for the majority of

the artefacts. Because the moat is waterlogged organic remains have

survived very well, particularly leatherwork. Soil samples from the

moat should also tell us a great deal about the local environment at

the time and the living conditions of the townspeople.

The foundations of the hall were cut into a grey soil layer which

is suggested as being a former ploughsoil. If true it would indicate

that the hall was laid out on the site of the town fields. Detailed

micromorphological analysis will be undertaken to confirm the

interpretation. |

| The work has been funded by the City of Wolverhampton

College and Wolverhampton Adult Education Service who are jointly

developing a Learning Centre on the site.

The archaeological excavations have now been completed and the finds

and records are being worked on at Birmingham University with the

intention of completing a report on the site in 2003. An open day to

view the excavations early in December attracted over 500 people and was

covered in the local press (Express and Star, Wolverhampton Ad News),

radio (Radio WM, Saga FM) and television (Midlands Today). Discussions

are currently being held with Wolverhampton Museums and Art Gallery and

it is hoped that an exhibition of the finds and results of the

excavation can be arranged for early 2003 at Bantock House Museum. Watch

this space!

Mike Shaw, Black Country Archaeologist, 20.12.02

|

|

A map of the site, made from a

sketch taken of a poster that was on display during the open day. |

| The view of the excavation from the

south. The grey soil in the foreground is believed to be former ridge

and furrow plough soil, suggesting that the building was built on open

farmland. On the right is a mixture of foundations of 'The Great

Hall' and some 19th century buildings. The former moat can be seen at

the far end of the site. |

|

|

The south-eastern corner of the site

showing the grey ridge and furrow plough soil and some early foundations

surrounded by 19th century brick structures. |

| A mixture of original, and 19th

century brickwork. The moat, which is on the far left had been filled in

by 1842 and the building was extended as part of a Japanning works. The

building originally became a japanning factory in 1767 when it was owned

by Jones and Taylor. In about 1820 it was taken over by Obadiah and

William Ryton and continued as a japanning works. In 1842 the company

became Walton & Co. |

|

|

The same view from the eastern side

of the excavation.

The japanning factory closed in 1883,

everything was sold off and the building demolished. |

This view shows the moat excavation

from the west. The brickwork in the foreground is part of a 19th century

cellar.

A number of 16th and 17th century artefacts were recovered from this

part of the excavation. These included glass, tableware and a silver

spoon. Because the area is waterlogged organic remains are well

preserved. Items found here included leather shoes. |

|

|

A view of the moat excavation from

the opposite side. This part of the excavation uncovered what are

believed to be the original foundations of the building. They consist of

massive stone foundations about 1.5m wide and are cut into the original

plough soil. The moat was not a defensive structure as in a castle but

was a status symbol, a declaration of wealth. |

| A group of visitors inspecting some

of the finds which were on display. In total there were 35 boxes of

finds, mainly consisting of pottery and glass fragments. There was also

a horse's skull which was retrieved from the moat. The remaining parts

of the skeleton may still be in the unexcavated part of the site. |

|

|

An example of the high quality 16th

/ 17th century pottery that was found on the site. This shows that the

building was of a high status at the time. Later pottery fragments from

the japanning days are of a much lower quality illustrating the change

of use of the building. |

| Another fine example of the high

status 16th / 17th century pottery that was discovered here. |

|

|

Two further examples of well- preserved high

status tableware that were found on the site. |

| The horse's skull that was removed

from the moat. |

|

The excavation was the culmination of three years work

to locate the Old Hall. Much work remains to be carried out on the finds

which will be studied and conserved. The organic remains found in the

moat should tell us a great deal about the local medieval environment,

what plants were grown and what food was eaten by the inhabitants. When

this work has been completed it will provide a unique insight into

medieval life in Wolverhampton.

We would like to thank Mike Shaw for his help and

contribution to this article.

|

|

Return to the articles

section |

|