| "The appearance of the country around

Wolverhampton and Bilston is strange in the extreme. For miles

and miles the eye ranges over wide-spreading masses of black

rubbish, hills on hills of shale, and mashed and muddled coal

dust, extracted from beneath and masking, as it were, the whole

face of nature."

This description of the area, written in

the middle of the 19th century, paints a vivid picture of an

unpleasant, unhealthy place in which to live and work - the

harsh reality for many of the working classes living in the

industrial areas of England.

Lives were hard and short, and the people

found their entertainment and leisure where they could, more

often than not in the public houses, of which, in Bilston, it is

said that, at the end of the 19th century there was one for

every 140 inhabitants, including children.

The desperate need for public open spaces

to provide those living in the rapidly growing towns with

opportunities for health recreation, was recognised by the early

years of the 19th century but it did not become a reality until

the 1840s when the first public parks were opened in Derby and

Manchester. Birmingham was not far behind, opening their first

park in 1856, but in Wolverhampton, the people had to wait until

the summer of 1881 for the opening of what became known as West

Park.

|

|

West Park Conservatory built in 1896. |

The council had first set its sights on the town's

race course as the ideal location for a park as early as the

1860s, but it was not until 1879 that terms were agreed with the

Duke of Cleveland who owned the land, when he finally agreed to

a 63 year lease of the site with an option for the council to

buy the land at the end of the term.

From the outset the council was determined that the first

park in the borough should be state of the art. |

| A special sub committee toured the country

looking at the best examples, and advice was sought from the

leading experts in the field. |

|

The eventual design of the park was the

subject of a national competition, won by Richard Hartland

Vertigans, a landscape designer and nurseryman with premises in

Malvern and Edgbaston. His task was not an easy one. To begin

with the site was described at the time as a "treeless swamp" so

a lake would be essential to help drain the land.

The council also specified that the park

should be surrounded by stout railings, and two lodges for park

keepers were to be provided.

|

Boating on West Park Lake. |

|

In keeping with the latest trends,

Vertigans made provision for archery, cricket, bowling and

volunteer drill in his design, as well as the planting of trees

and shrubs. Many gifts were made to the park in the early years,

including ducks and swans for the lake, several glacial

boulders, a four faced clock, which still overlooks the flower

beds at the centre of the park, and at least two drinking

fountains. But the most generous gift was that of Charles Pelham

Villiers, MP for Wolverhampton, who was unable to attend the

grand opening of the park, but, instead, gave a beautiful cast

iron bandstand.

|

|

West Park entrance. From an old postcard. |

The park's crowning glory, the

conservatory, was built in 1896, with the proceeds of the town's

Floral Fete, held every year in the park. It was designed by

Thomas Mawson and his architect partner Dan Gibson, who were

advising the council on their second park at the time.

Other improvements in the early years

included new paths around the lakes, the erection of the

lakeside shelter and a tea room called The Chalet, which was

opened in 1902.

|

While the park gradually

evolved over the first 20 years of its existence, Vertigans'

original design of 1897, a plan of which is held in the council

archives, remains virtually unaltered to this day.

The new park soon proved itself a huge

success and a great benefit to the people of the town. However,

its location on the more affluent west side of the town meant

that it was of limited use to those living in the more heavily

industrialised areas to the south and east.

East Park

There was rising political and public

pressure for a comparable park to serve the east end of town and

in 1892 Sir Alfred Hickman and the Duke of Sutherland offered a

gift of 50 acres of land, just off the Willenhall Road, to the

Corporation.

It was, however, a difficult site

consisting largely of collapsed and exhausted mine workings of

the former Chillington Colliery which would require considerable

reclamation in order to create a park.

Once again the council held a competition

for the design, but all the entries far exceeded the budget

allowed for the project.

One design did, however, catch the eye of

the judges - that by Thomas Mawson, who had recently completed

two public parks in the Potteries, and was to become recognised

as one of the outstanding landscape designers of his time.

|

The council decided to use

his basic concept and retained his services to assist the

Borough Surveyor in development of the plans.

Mawson seems to have remained closely

involved with the park and attended site inspections during

works, and the opening ceremony.

The Mayor at this time was Charles Mander,

and Mawson so impressed the family that he was later

commissioned to remodel the gardens at Wightwick Manor.

|

East Park bandstand. |

The final design, a copy of

which is held in the city archives, shows 11 acres of sports

grounds, a children's play area, an open air swimming pool, a

lodge, toilets and areas of shrubberies and flower gardens.

However, the main feature was a 10 acre boating lake with a

promontory on the east shore which was to be the location for an

eyecatcher.

The Lysaght Memorial Clock Tower was

erected on the site in 1887. Although not shown on the borough

surveyor's plan, a bandstand was also erected in the park, paid

for from the proceeds of the annual floral fete. Implementation

of the scheme proved to be both difficult and expensive, and the

budget was soon exceeded, but eventually all was completed and

on September 21, 1896, crowds gathered on a rainy afternoon to

witness the grand opening by the Mayor and Mayoress.

|

|

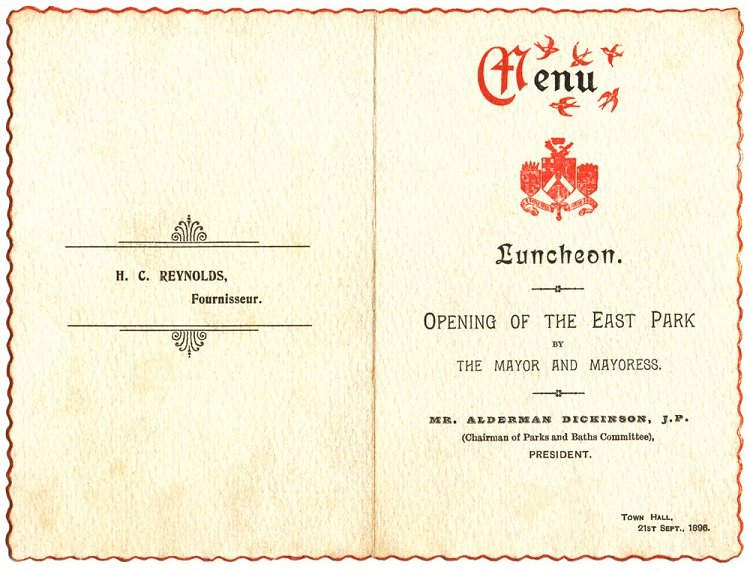

After the opening, the principal

guests were invited to a luncheon at the Town Hall.

Courtesy of David Clare. |

|

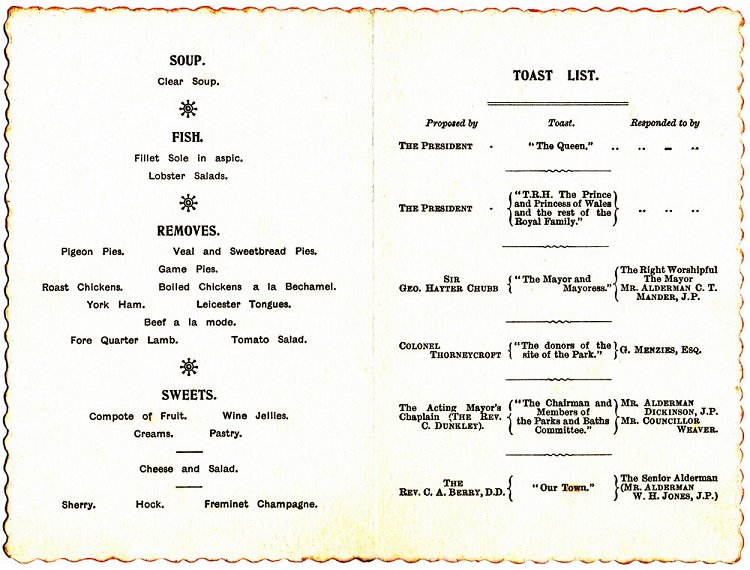

The food and the toasts at the

Town Hall. Courtesy of David Clare. |

|

The East Park, as it became known, was

beset with problems from the outset. The main entrance was 200m

from the Willenhall Road across rough ground, reported to be

ankle deep in dust in the dry weather and deeper in the wet.

Both the Duke of Sutherland and Sir Alfred Hickman had retained

ownership of the surrounding land, no doubt hoping to reap the

benefits of any new developments which would be attracted by the

new park, but this did not materialise and well into the 20th

century the park remained surrounded by open land.

The lake, however, proved to be the biggest

problem. Even during construction there were problems with

leakage into old mine workings and, despite efforts to retain

levels, by pumping water from a specially bored well and

numerous repairs, the lake gradually disappeared. Efforts to

save the lake ceased during the 1914-18 war and by 1922 the area

was reported to be covered with grass. The East Park was never

the huge success its western counterpart had been.

The area surrounding the park was not

developed with housing until the middle years of the 20th

century, and the loss of the lake as an attraction was a major

blow to its popularity, but there was a revival in its fortunes

in the post war period when a paddling pool and new sports

facilities were introduced to serve the new housing which had

grown up around the park.

Hickman Park

After Wolverhampton had celebrated the

opening of its second municipal park a campaign was launched in

neighbouring Bilston to raise funds to open a park, by public

subscription. However, by 1910 only £600 had been raised. It was

then that the family of the late Sir Alfred Hickman offered, as

a memorial, to purchase a site and layout a public park.

The site chosen was that of Springfield

House and grounds, just a mile to the west of the town, plus an

adjoining field which, together comprised 12 acres. The design

was drawn up by the Borough Surveyor. The original drive through

the estate was retained but a new grand entrance was constructed

off Broad Street.

Lawns and paths were laid out and trees and

shrubs planted. At the centre of the park a cast iron canopied

drinking fountain was erected which was paid for by public

subscription to commemorate the Coronation of George V. Opposite

this a timber shelter was erected next to a grotto, complete

with a pool and fountain.

|

|

Hickman Park. From an old postcard. |

Lady Hickman made a special gift of a new

and rather unusual bandstand constructed of reinforced concrete.

As with many parks, Hickman Park continued

to evolve over the years. The most significant changes were in

the inter-war years when sports facilities were laid out and an

indoor theatre built with funds raised by Bilston Horticultural

Society.

|

|

Studying the history of our parks we become

aware of how hard ordinary people and politicians battled to

provide public parks at a time when our towns were growing at a

faster rate than ever before and pressure on land was enormous.

Their role in providing opportunities for

recreation and access to green open spaces is just as valid

today as it was a hundred years ago. But today, they must be

valued as part of our heritage, comparable to those examples of

Victorian architecture which provide some of our most treasured

landmarks.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|