The Second Edition

|

The second edition was slightly larger and included

articles on G.W.R. engine number 35, the Portobello Junction accident of

1899, the G.W.R. model locomotive, mixed gauge rail at the Low Level

Station, a drawing of S & B locomotive number 23, part 2 of 'Working at

Bushbury Shed', "Airship" tank engines, 'Robert Plant - Stafford Road

driver', and part 2 of the compilation of principal events in

Wolverhampton's railway history. Some of the articles give a good

impression of what life was like, working on the railways. 'Working at

Bushbury Shed' and 'Stafford Road Driver', both describe a world that is

now gone, a way of life that has changed beyond recognition. The

articles on G.W.R. locomotives are informative and provide useful

information for anyone that is interested in steam engines.

The cover photograph shows an 'Experiment' locomotive at Bushbury. |

Accident at Portobello

Junction 1899

| Bushbury sidings were clamped in a wet fog during the early hours of

October 19th 1899. In the gloom stood a massive goods train of 45 wagons

awaiting a clear road to Birmingham. Driver John Mason and Fireman

Thomas Summers may have seen, or at least heard "DX" locomotive No.278

as it worked off nearby Bushbury shed en route to High Level station to

collect its train. The "DX" swung off the old line and onto the Stour Valley link with

High Level. At the regulator was Driver Alfred Humphries, a forty year

old married family man. He lived close to the shed at Sherwood Terrace,

Bushbury Lane. His fireman, Francis Davis, lived a little further away

at South Street, he was twenty eight. At the station the two men

reversed the engine onto the London train, consisting of six coaches and

two vans. They were due to leave at 5.50a.m.

At 5.43 Driver Mason got his goods train under way, increasing speed

only slowly. The rails were wet and the train weighed 450 tons, falling

on the absolute weight limit set by the company. Speed increased as the

train began the approach to Portobello. Driver, fireman and guard saw

all three signals in the Wednesfield Heath area showing clear for the

section approaching the junction. These were the last signals seen as

the train rolled into a blanket of dense fog. Meanwhile at High Level,

the passenger train started on its way along the loop line to the

junction with the main line at Portobello. |

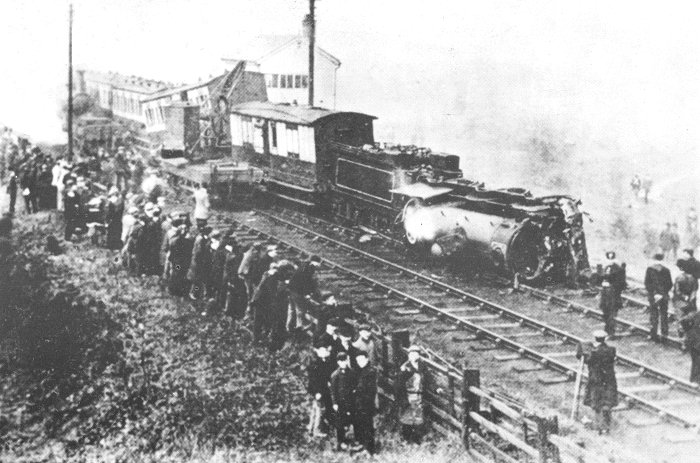

The fog has cleared in this photograph,

taken from the road bridge in Neachells Lane. The lightweight crane

in the background would be insufficient on its own to raise the

locomotive, the L.N.W.R. having only one heavy crane on its system

at this time. No doubt after much manhandling the ‘D.X’ was taken

off to Bushbury shed for examination. Surprisingly, despite it being

an early example of its class, (built 1861) No 278 was repaired and

put back into service, surviving until 1919. |

| Signalman Charles Povey was working a ten hour shift

at the junction signal box, where he had been stationed for the last

five years. The line was worked on the absolute block system, with

only one train allowed in the section at any one time. Povey did

what he had done all those years, and ignored the rules. He accepted

both trains into his section, setting the junction signals against

the goods train. He expected it to stop as trains always had before,

at the home signal.

"It all seemed so simple", he said at the later enquiry.

On the footplate of the goods train both men were straining

their eyes for a glimpse of the distant signal controlling the

junction. In his van Guard Robert Thomson did the same. The fog was so thick that

none of the men could make out the signal post, let alone the signal

lamp up behind the spectacle glass. The driver noticed that they had

passed a level crossing and that the Crossing lay beyond the invisible

distant signal. He threw the engine into reverse. In the van Thomson

felt the train lose speed and applied his own brakes. The rails were

wet, the 450 ton train was running on a downhill gradient, and the

braking was supplied by the engine and the guards van alone. The crew

could do no more as the train ran out onto the junction. It was still

impossible to see any signal light, but the shriek of an approaching

locomotive whistle warned them of their impending fate. Driver Mason

opened the regulator in a desperate attempt to outrun the train bearing

down upon him.

Harry Kay (this is the name given in the newspaper at the time, a

descendant claims it to have been 'Clem' Kay) was an engine fitter on

his way to work at a Willenhall factory, he was approaching the bridge

at Neachells Lane when he heard the warning whistle of a locomotive in

the fog. He heard the sound of another engine, the beat of its exhaust

increasing sharply as it attempted to put on speed. A tremendous bell

like sound signalled disaster. As Harry Kay stared out over the bridge,

along the line he saw a solitary locomotive appear from the mist,

drawing a few goods wagons. The workmen staggered and fell down the

embankment as he went to the help of a train that he could not see.

|

Sherwood Terrace in Bushbury Lane, as it

stands today. Like most railwaymen, driver Alfred Humphries lived

within sight of his work. The railway bridge can be seen from the

front garden. Photograph Mervyn Srodzinsky. |

| Shattered goods wagons loomed out of the fog. The

locomotive of the passenger train lay on its side roaring steam. The

mutilated remains of the fireman lay beneath the tender. Kay opened

the steam valves to prevent the boiler exploding and went to help

where he could. Passengers were standing around in the mist, shocked

and confused. John Westwood, the guard of the passenger train had

been thrown across his van in the impact, recovering consciousness

some minutes later. He instinctively checked his watch as he got up,

it was 3 minutes past 6. He re-Iit his lamp and went the length of

the train but could find no sign of the locomotive crew. He set off back along the line towards Wolverhampton, laying fog

detonators along the way. Meanwhile Driver mason had continued to

Willenhall determined to warn the crew of a goods train, due at the

junction in a matter of minutes. He was successful, and returned with

his engine to render what help he could at the accident.

Driver Humphries had been found, badly injured at the bottom of the

embankment. He was lifted into the goods engine and taken to Walsall

hospital, where he died from his injuries. Amongst all the wreckage, a

bottle of tea belonging to one or other of the unfortunate men was found

unbroken. The fireman's watch and chain was also discovered, the bar and

several links were still attached to the dead man's waistcoat.

|

|

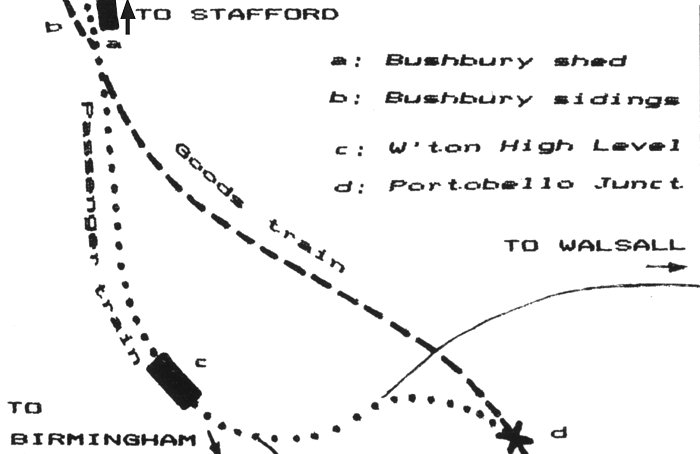

The location of the accident. |

| At 9.30a.m. the recovery crane arrived from

Bushbury, but work was hampered by the fog which was still heavy.

Shattered wagons were rolled down the embankment out of the way.

Another team arrived from Birmingham and a hundred or so men worked

through the day to clear the line. The damaged locomotive was left

where it had come to rest, still leaking steam at midday. Crowds of

sightseers descended in their hundreds as the mist cleared, arriving

in elegant carriages, hansoms, carts, or on foot. Photographers set up their equipment to record the occasion. Fireman

Davis was laid to rest at Bushbury cemetery on the Monday morning. He

was a member of the Mount Zion Bible Class as was the Mayor of

Wolverhampton, who spoke a few words at the graveside. A large number of

railwaymen were there as well. Some days later Alfred Humphries joined

his fireman, again escorted by a large body of work colleagues and

neighbours come to pay their last respects.

The subsequent enquiry report criticised the railway company over their

failure to employ fogmen over the section. No one ever laid fog

detonators along that stretch of line between the hours of 7p.m. and

7a.m. in the mornings, due the company said, to staffing problems. The

poor braking of the goods train was also mentioned. The main fault lay

however with Charles Povey, the signalman.

|

A view from the other side of the accident.

The carriage on the left of the picture appears to number 872 and is

a five compartment all third, as is the second along. The third

vehicle has a centre luggage compartment. An L.N.W.R. policeman

stands beside the train, receiving instructions. Portobello was a

notoriously poor area at this time, and the local population made

short work of emptying the shattered goods wagons of their contents

as soon as darkness permitted. Courtesy of N. Tildersley. |

| He admitted that he bad broken the rules in allowing

the goods train to proceed beyond Wednesfield Heath, but said in

defence that he had always done the same. On the few occasions when

an inspector had checked his train logs no mention had been made of

his malpractice, nor had a train ever overrun the junction signals

before. The morning of October 19th 1899 proved the exception which

made the rule a necessity.The fate of Signalman Povey is not

recorded. He almost certainly lost his job, but the real punishment

must have lain in the memory of the events that took place outside

of his signalbox window, the shrill sound of an approach whistle,

the desperate beat of the goods engine struggling to clear the

junction, and the roar of the collision, all hidden from sight in

the fog. Of such things were Victorian nightmares made....

References:

Wolverhampton Chronicle, Express & Star October

1899.

British Locomotive Catalogue, 1825-1923 Vol. 2A by B & D Baxter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Edition 1 |

|

Return to

the Beginning |

|

Proceed to

Edition 3 |

|