|

|

In the mid eighteen forties, in essence prior to Nightingale, a group

of Victorian philanthropic businessmen in Wolverhampton were determined

that the town was worthy of a hospital as an alternative to a six bedded

dispensary.

Duty was done and a total of some £18,000 was raised which purchased

land from the Duke of Cleveland, and a fine portico fronted hospital

with 84 beds was built with the residual £14,000 plus.

|

|

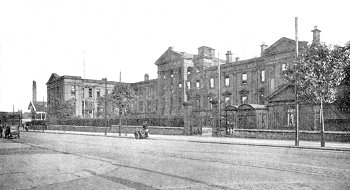

A late 1920s view of the hospital. |

The hospital opened its doors in January Ist 1849

to "patients who are such unable to pay for medicine and advice

and are destitute of funds to make provision for them". It was

run by a non-stipend Board of Governors and was totally reliant

for its complete running costs on charity. |

| By the turn of the century, the hospital was

recognised for training doctors and nurses and had established a

pathological laboratory (albeit in a shed), a steam laundry,

medical library, hospital chaplaincy, electricity and a new

kitchen. By the year 1912 the hospital had developed a 53 bed

nurses home, a new wing of beds dedicated to King Edward VII,

its own motorised ambulance provided by Wolverhampton Police

Force, an electric lift and a new laboratory. |

| During the First World War, much use of its

facilities was made for the war wounded from France. Lady

doctors were used for the first time, and many of the staff

themselves gave war service. In the ten years immediately after

the Great War the hospital added many new departments and wards,

including operating theatres and VD clinics. The hospital was

visited by the Prince of Wales and granted its Royal Charter. By

1928 it became known as the Royal Hospital, losing one of its

former names of Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Hospital. |

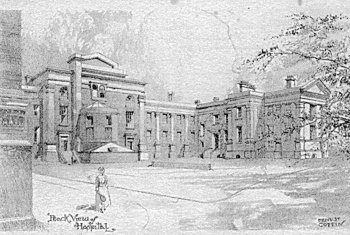

A postcard from a series printed in the

1920s to raise funds for the hospital. Courtesy of Neil Fox. |

| During the nineteen thirties, the Royal Hospital

acquired the reputation of being one of the best provincial

non-teaching hospitals in the country. This was largely due to

the work of three men - J.H. Sheldon, R. Milnes Walker and S.C.

Dyke.

Sheldon came to Wolverhampton from Kings College Hospital

after the first world war and was a pioneer of the 'brains

drain' from the teaching hospitals to the provinces which began

to raise the standards from largely G.P. part time hospital

staff to consultant- led institutions. He gained national

recognition in 1986 when he published a monograph on

haemochromatosis based on his own observations - a work still

referred to in the literature. His clinical reputation was

enhanced by a classic account of an outbreak of trichomaniasis

during the second world war. Soon after the war he produced his

important report on the medicine of old age. He used to say that

one of the most valuable services for the elderly was the

marketing by Woolworths Stores of simple convex lens spectacles.

At that time nothing in the store cost more than 6d (2.1/2p), so

that many elderly people were able to read again. This work was

an important factor in the formation of the new speciality of

geriatric medicine, and for some years Sheldon became a leading

authority on the subject. |

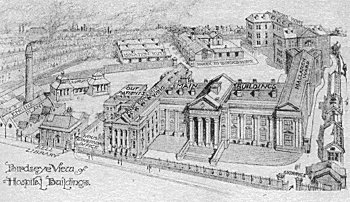

Another postcard from the series printed

in the 1920s to raise funds for the hospital. Courtesy of Neil

Fox. |

Milnes Walker acquired a considerable reputation

as a surgeon and attracted patients from a wide area. He had a

large family and became so busy that his home life was severely

affected. Shortly after the war, his talents won him the post of

Professor of Surgery at Bristol, so sadly, Wolverhampton lost

him. |

| Dyke also came to Wolverhampton from a London

teaching hospital in the early 30's. He was an excellent

histologist and had the quality of admitting when he did not

know. He developed an interest in diabetes and was one of the

first to use insulin. As late as the early sixties he used to

demonstrate a patient still in good health who was said to be

the fourth subject in the country to have been given insulin.

His diabetic clinic was huge and he used to sit at a desk raised

on a small platform while the patients filed past him, as there

was still little space for waiting in the laboratory; it was a

familiar sight to see a queue of people with raised umbrellas

outside the laboratory door. He was involved in the trials of

the antibiotic "M & B 693" before the discovery of penicillin.

He had something of a flair for showmanship and formed the

European Association of Pathology.

With such well known figures in a provincial hospital, it is

hardly surprising that bright young men were attracted as

residents, and when the bombardment of London began in 1940 and

the city's medical schools were moved out of danger, the

Middlesex Hospital sent students to the Royal Hospital. Some of

these, delighted at their experiences, returned after

qualification as residents and later settled in the town as

consultants and G.Ps. |

| In the late thirties a complete new wing of five

floors containing 120 beds and a fine swimming pool was added.

By the forties the hospital had developed into an excellent

general hospital encompassing all the necessary medical

specialities and facilities, including cancer treatments. During

the Second World War it again received many war wounded. In 1948

it was handed over to the NHS with its books in the black and

having been developed and run for 100 years on the charity and

zeal of Wolverhampton's businessmen and worthy citizens. |

The hospital building as it is today. |

| During the fifties, in addition to its excellent

male and female Nurse Training School of some distinction, it

established both Physiotherapy and Radiography Schools of

similar note. Its quality of care and training of staff became

legion throughout the UK with increasing numbers of overseas

medical, nursing and physiotherapy students arriving. In the

early fifties a Nurses League, Hospital Friends and Nurses

Christian Movement was established. Considerable improvements to

patient services were seen, and a new kitchen was built. |

|

The hospital buildings in 2003. |

Throughout the sixties and seventies a new theatre

suite and I.T.U. facility, plus a coronary care unit were

established; however talk had begun to move the hospital’s

facilities to the out of town New Cross Hospital site of some 60

acres, albeit a former workhouse. |

| This decision was finally enacted, and the Royal Hospital

closed on Tuesday 24th June 1997 after more than 148 years of

care and dedication to the citizens of Wolverhampton, thus

ending a centre of excellence in the epicentre of Wolverhampton

Millennium City. |

|

Return to

the

health section |

|