|

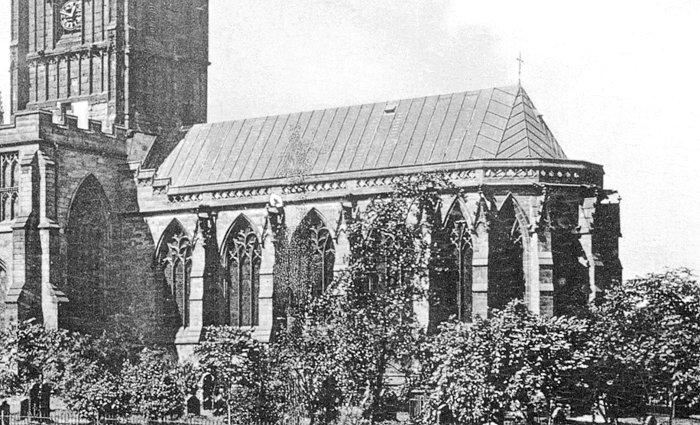

We are all familiar with Ewan Christian’s

extant chancel (early-1860s), its collegiate arrangement

of seating, and the polygonal apsidal termination.

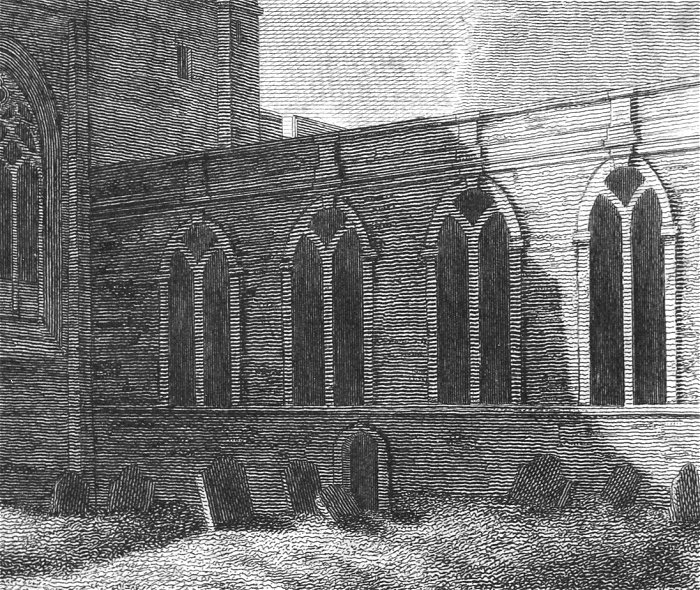

Also

well-known is the 1682-4 chancel, seen in the engraving

found in Robert Plot’s Natural History of

Stafford-shire (1640-1696) (an illustration

depending, probably, on the oil painting kept in the

church’s vestry), and we are very fortunate indeed to

possess a photograph of that building.

The illustration from Robert Plot’s Natural History of

Stafford-shire.

1

Regarding the Medieval

chancel (late 13th century?), however, there

is no visual record (that I know of – hopefully I am

wrong). It was known as the ‘Great Chancel’ or the

‘Dean’s Chancel’, Roper tells us.

2 A written record (quoted by Mander

3)

tells of its alleged ruinous state in 1665 (prompting

creation of the 1680s chancel) – but nothing else about

it.

Most English churches, large and small,

are square-ended, even when great churches have a

(square) ambulatory behind the high altar/shrine;

however, some great churches have a fine polygonal

chevet, in the ubiquitous French fashion (Canterbury and

Norwich cathedrals, and Westminster Abbey), and a few

have a more simple octagonal termination. It may just be

that such a regional fashion obtained in what we now

know as the West Midlands: St. Michael’s Coventry

(1373-1500; 1883-90,

4);

Lichfield’s eastern termination, the Lady Chapel

(1310-30?); and perhaps that of St. Mary’s, Coventry,

which possessed a set of three projecting chapels (15th

century?), foundations of which were unearthed in 1955

5;.

Aston’s Medieval parish church gained a polygonal apse

in Julius Chatwin’s rebuilding (1879-90), and he may

have been following Medieval precedent there (though

Andy Foster suggests

6

the influence of St.

Michael’s. Coventry, which, as we have seen, was being

rebuilt at this time).

While Ewan Christian’s July 1860 report

on St. Peter’s (Salt Library, Stafford) refers to the

ruinous state of the 1680s chancel – and its utter

meanness and ugliness - he gives no information about

its predecessor

7. Shortly

afterwards, he was building the chancel we see today,

and his builders most likely discovered the foundations

of the Medieval building (just as Basil Spence’s

builders unearthed the foundations of St. Mary’s eastern

chapels, when beginning work on Coventry’s 1962

cathedral). With St. Peter’s chancel foundations (as

surely was the case at Coventry – though those

foundations were not going to be built upon) it would

not have been (financially) worthwhile for those who

demolished the building, to dig them up and remove them.

Is it possible that Christian decided to re-use the old

foundations, and rear his new building upon them (the

urge to avoid the unnecessary cost of setting new

foundations must have been irresistible)? Perhaps he had

already decided upon a polygonal apse, or, changed his

plans in favour of one, when (if) the old foundations

emerged; Chapter records might surely reveal discussions

about such a change of plan. Or it may be that the

Medieval chancel was shorter than Christian’s

(more akin to the 17th century chancel, and that that

– square-ended, as the photograph shows – may have used

(square-ended) Medieval foundations, so that the

Medieval chancel may have been the same shape, and size,

as its Seventeenth Century successor – but this is

unlikely if the Medieval chancel was, as suggested,

‘great’). (Christian’s restoration, etc., of course

(1852-65) involved much additional work on most parts of

the building.)

Many questions remain (another one is:

Just why was a building the size of the 1680s chancel,

or indeed any chancel at all, needed, at that time?

What went on in it?). While there has been some

geophysical research done north and south of the nave

8,

none has been done east of the extant termination –

would such investigation reveal any foundations (perhaps

the Medieval chancel was longer than Ewan

Christian’s)? Certainly, until there is research at that

end (that is, near the Art Gallery) we will not really

know, unless further documentation comes to light.

Hopefully, these matters and questions will be taken up

by future studies of the church’s building history,

which are badly needed.

| 1. |

Reproduced in John Roper,

Wolverhampton As It Was, Vol. 1, Nelson,

Hendon Publishing Company, 1974, the second

photograph, opposite the Introduction (the

book lacks page numbers). |

| |

|

| 2. |

John S. Roper, Historic

Buildings of Wolverhampton. A Study of 15

Buildings in the Town Dating from Mediaeval

Times to 1837, Wolverhampton, [no

publisher], 1937, p. 8. |

| |

|

| 3. |

G. P. Mander, ‘Wolverhampton

Antiquary’, Vol. 1, No. 11, pp. 330-341. The

information comes from a letter of John

Huntbach (10 April 1665) to his uncle the

antiquary Sir William Dugdale. Apparently

the chancel roof’s lead had been stripped

off. |

| |

|

| 4. |

John Thomas, Coventry

Cathedral, London, Unwin Hyman, 1987,

pp. 45 (plan), 58. |

| |

|

| 5. |

Thomas, work cited note 4, p.

33 (photograph). |

| |

|

| 6. |

Andy Foster, Birmingham

(Buildings of England), New Haven, Conn. ;

London : Yale University Press, 2005; entry

for

Aston. |

| |

|

| 7. |

D1157/1/8/13, in the

collection: Miscellaneous Accounts and

Papers Relating to the Collegiate Church of

St. Peter, Wolverhamton (collated c.

1966). |

| |

|

| 8. |

Roland Wessling, Report .

Assessment of the Potential for

Geophysical and Archaeological

Investigations to Determine the Presence or

Absence of Subterranean Structures

Underneath and Around the Church of St.

Peter, Wolverhampton, Shrivenham,

Cranfield University, DASSR, 2009. |

Much information regarding the history of

St. Peters church was given to me by Richard Wisker.

John Thomas

2018

johnalfredthomas@aol.com

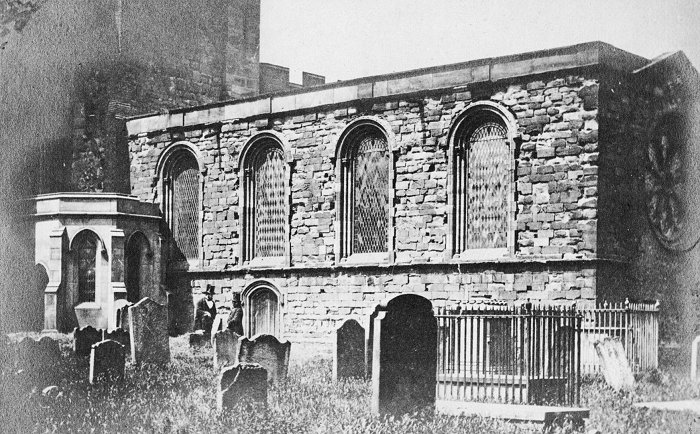

An Interesting Image

St. Peter’s Chancel; a Curious Image from a Glass

Slide.

A fascinating image of St. Peter’s

has come to light which possibly adds to the story (and

surrounding confusion!) regarding the chancel. This

originated on a glass lantern slide, scanned by Steve

Martin, and resides in the Archives Collection, probably

donated by the Wolverhampton Literary and Scientific

Society. David Clare made this available to me, after

extensive cleaning up, and removal of large smudges.

The western

portion of the image (of the church) may be

photographic, and may show the church as it was

after Ewan Christian’s restorations (1852-), but

before a new chancel was added. The eastern portion

may be a drawing added to the photograph, intended to

display to the client (the church authorities) the

appearance of a proposed chancel (or one of several

proposals?) which was never actually built (there

appears to be a tiny vertical join or break in the

image, at this point, suggesting addition). It may have

recommended a “Gothic” re-casing of the 1680s chancel

(its short projection may seem to suggest that).

Certainly, I think that St. Peter’s never had a chancel,

or eastern termination, the same as that shown on this

image.

My thanks

to David.

John Thomas

September 2019 |