|

In the 16th

and 17th centuries Wolverhampton was a thriving market

town. Although little has survived from that distant time, much can

be learned from the various old documents and records that are

stored in the local archives. A look through them can reveal much

about a long lost world.

The most

important source of information for this period is the Sutherland

Collection that has been on loan to the County Archives at Stafford

since 1959. The owners now wish to sell the collection at an asking

price of 1.9 million pounds and the archives are attempting to raise

enough money for the purchase. This is the unique archive of the

Leveson-Gower family, Dukes of Sutherland and contains much

information on Wolverhampton, including the 1609 survey of the

Leveson’s estate.

Another

source of information is the Paget Deeds and the Wolverhampton Town

Deeds, which are to be found in Wolverhampton Archives and Local

Studies on Snow Hill.

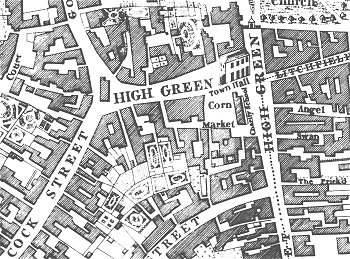

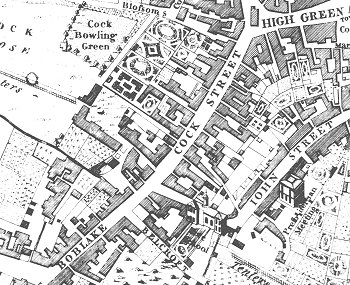

One item

not to be missed is Isaac Taylor’s map of Wolverhampton from 1750.

This is the first detailed map that was made of the town centre and

is always worth examining when considering the geography of the old

town. Many of the streets on the map were there in medieval times,

although the names may have changed. A dotted line on the map still

shows the old division of Wolverhampton into two manors, the Deanery

to the west and Stowheath to the east.

The

following brief description of some of Wolverhampton’s old streets

and buildings is based on information from the above sources, which

contain a vast amount of information on the town at the time. |

|

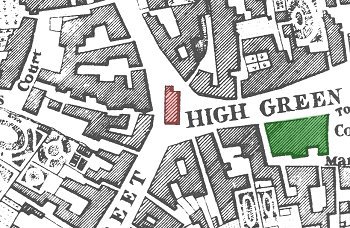

High Green from Isaac Taylor's map of 1750.

|

Wolverhampton centred, as it had for centuries before on

High Green, the old market patch. High Green ran from the junction of

Woolpack Street and Dudley Road, across Queen Square and up Lich Gates.

It also ran across Queen Square to the top of Darlington Street. There

was a late medieval cross standing on the east side of the Square at the

junction of the modern Queen Square and Dudley Street. In 1532 a market

hall was built near the cross, adjacent to where Staffordshire Building

Society is situated today. |

|

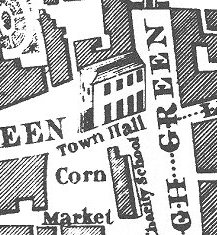

John Huntbach, who researched the now lost early Churchwarden’s

accounts, mentioned in his notes that the market hall was erected

“at the charge of the town”. The building measured 68ft. by 29ft. 4

inches and was later known as “The Old Town Hall”. It had a large

upper room (where the Assizes were held) that was supported by stone

pillars. The building was demolished in 1778 as a result of the

first Improvement Act of 1777 "for Widening, Cleansing and

Lighting the several Streets, Lanes, Alleys, Ways, and other public

Passages, within the Town of Wolverhampton, in the County of

Stafford, and for Taking down, Altering or Rebuilding certain

Buildings therein mentioned, and for removing all other Nuisances

and Encroachments, and for Regulating Carts and other Carriages

within the said Town." |

A close-up of Taylor's map showing the "Old Town

Hall".

|

|

William Addames, a Wolverhampton butcher was

granted a lease by John Leveson on 9th October 1577. This

is recorded in the

Sutherland Collection and describes Addames’ shop as follows “in the

South end of the Shambles Hall” with the “uprooms or buildings over

the same”. Another lease, also referred to in the collection, dated

23rd

March, 1630 calls the building “the Townehall in Wolverhampton”.

At the

northern end of modern Dudley Street was the Charity School, also

marked on Taylor’s map. It was purchased by the Town Commissioners

in 1779 to be demolished, like the market hall under the 1777 Act.

It was known as “Upper Butcher’s Row” or “Over Butcher’s Row” and

was owned by at least 5 vendors. The Wolverhampton Town Constables

Accounts state that both this building and the

market hall were used by the trustees of the school at various

times.

|

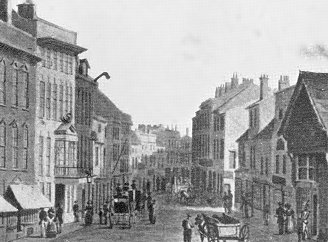

Dudley Street in 1835. From Noyes' drawing of

High Green. |

The Sutherland

Collection contains many details of High Green and states that the land

from modern day Woolpack Street to Queen Square was in the manor

of the Prebend of Hatherton, and included a medieval horse mill that

stood on the corner of Woolpack Street and Dudley Street. In 1609 a

detailed survey of Sir Walter Leveson’s Wolverhampton estates was

carried out and it includes details of the Swan Inn that stood where

Lloyds Bank is today. At the time the inn was leased to John Aldersey,

whose land went across to Piper’s Croft where there was a large barn. |

| Piper’s Croft was a large field, roughly in between

modern Queen Street and Castle Street. The Swan is also referred to in

the surviving Wolverhampton Town Deeds. Sir Richard Paget’s Oldfallings

deeds contain details of a lease dated 26th February, 1516.

The Swan was then owned by Richard Lane of the Hyde, Brewood and was

leased to John Baxter. At the time the Swan was being either wholly or

partially rebuilt after a fire. |

|

In the 1770s the town’s first theatre was built

in the yard behind the inn and described in a report in a

Wolverhampton Chronicle of 1894 as follows:

The building was a plain but substantial brick

structure about 80ft. long by 36ft. in breadth, with two entrances –

one to the boxes (or dress circle) facing down the Swan Yard, and

the other leading to the pit and gallery, being opposite the opening

or gateway entrance from Wheeler’s Fold. The interior was almost as

plain as the exterior, there being little attempt at artistic

embellishment or decoration, except in the vicinity of the stage,

which occupied the entire breadth of the building at the east end.

It is estimated that the theatre seated about 600

people.

Also listed in the 1609 survey is a large house

leased to Elizabeth Pershouse. The house was close to the swan and

the garden extended to Piper’s Croft. A nearby house and shop were

leased to John Wightwick and close by stood the houses of John Key

and Richard Shenton. Each house had a sizeable piece of land at the

back. Elizabeth Pershouse paid 30s a year rent for her house, John

Wightwick paid 31s.4d. a year and Richard Shenton paid 36s a year.

|

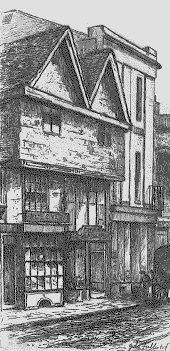

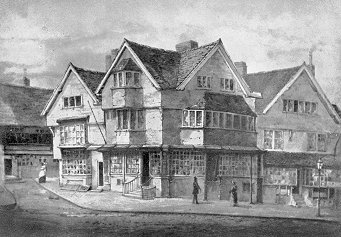

John Fullwood's drawing of 19th century shops in

High Green, Now Dudley Street. |

| The houses on the western side of the street appear to

have been smaller. One was rented by Henry Smythe who also rented

Culwalle Meadow and Whytmore Reaynes pasture from the Levesons.

At this time the southern end of Dudley Street was less populated.

Bell Street was then known as Hollow Lane and used to extent to

Dudley Street (until the 1970s). There were two houses in Dudley

Street adjoining the junction with Hollow Lane. The first was rented

by Richard Brett, who paid 15s a year and the other tenant, Hugh

Sambrooke, paid 16s.4d. a year. These cottages were opposite the

main entrance to the Old Hall, the Leveson’s home.

|

|

High Hall shortly before demolition. By R.

Noyes.

|

The Leveson family also owned a grand house on High

Green approximately where Wolverhampton’s Information Centre stands

today. It was known as High Hall and was a fine 16th

century half-timbered building that survived until1841.

The Sutherland Collection contains leases for the house from about 1620

to 1654, but many are badly damaged. One that has survived is dated 20th

April, 1654 and was granted by Sir Richard Leveson of Trentham to

William Normansell senior, for a term of 99 years.

|

|

The

rent was £10 per year with two fat hens at Christmas and two fat

capons at Easter. When the lease was granted he had to pay a heavy

£200 premium and Mr. Leveson reserved the right to use any of the

rooms in the house at will. The lease also included a great deal of

arable land, meadowland, pastures, closes and crofts, all in the

outskirts of Wolverhampton.

The

collection of Wolverhampton Town Deeds includes deeds for the house

from 1705 to 1841, when it was purchased by the Town Commissioners.

One carries an inventory of some of the rooms as they were in 1780

when the occupier was Peter Talbot, a mercer and draper. At the time

the business was taken over by James Hordern. By 1841 the house had

been divided into two parts, the upper shop and the lower shop.

Immediately behind High Hall in the early 19th century

were two inns known as “The Wheatsheaf” and “The Lamb” and on the

western side of the house was a block numbered 25, 26 and 27 High

Green. A deed from 1738 contains information on the block, much of

which was occupied by Sarah Unett and Thomas Bradshaw, an

apothecary. The gardens at the rear are visible on Taylor’s map and

were known as “The Little Garden” and “The Great Garden”. In 1899

the block was owned by Edgar Harley who ran “Harley’s Vaults” from

number 25, the remainder being rented to Messrs Picken and Waring

who were drapers.

|

| Taylor’s map

shows an isolated building at the western end of High Green, known as

“The Roundabout”. The ancient building stood in-between Cock Street and

Goat or Tup Street (now North Street).

It is described in one of

the Town Deeds dated 3rd August, 1682 as a burgage or

tenament owned by John Southwicke, a Wolverhampton saddler who sold

it to Jonathan Farrian and Thomas Skett for £220.

|

Part of Isaac Taylor's map of 1750. "The

Roundabout" is coloured in red and High Hall is coloured green. |

| Sometime

before 1783 the building had been divided into two halves because in

that year the half owned by Thomas Jarvis was acquired by the Town

Commissioners. From 1788 Samuel Adey, a mercer and draper occupied the

other half of the building. He sold it to the Town Commissioners in May

1815 and “The Roundabout” was demolished to make way for the building of

Darlington Street. One important feature associated with “The

Roundabout” was one of the town centre’s water pumps, which survived

after the building was demolished. The edition of the Wolverhampton

Chronicle for the 8th March, 1820 contains an article that

states that the materials from the building were sold by auction to the

highest bidder.

|

|

Cock Street and Boblake as shown on Taylor's map.

|

At the south

western corner of High Green was Cock Street and Boblake, renamed

Victoria Street after the Queen’s visit in 1866.

Cock Street was probably

named after the “Cock Inn”, which stood on the western side of the

street approximately opposite Lindy Lou’s, the only surviving 17th

century building in the street. The “Cock Inn” burned down on 22nd

April 1590 after one of the many fires that took place in the area

and destroyed many of the timber-framed buildings.

|

| In fact in

Barn Street, now Salop Street, 104 houses were bunt down and 694 men,

women and children were “impoverished by the fire” and 30 stacks of hay,

corn and straw were destroyed.

Cock Street was previously

known as Tunwell Street or Tunwalle Street, which is derived from

the words town well, the name is perpetuated in Townwell Fold. An

account of the wells can be found in Robert Plot’s “Natural History

of Staffordshire” from 1686. The wells were situated behind the

“Cock Inn” and so were roughly where Beatties store stands today.

The lower part of the Street (Boblake on Taylor’s map) was a marshy

area through which ran the town brook. It is called Puddle Brook on

Taylor’s map and ran down from Snow Hill towards Chapel Ash.

|

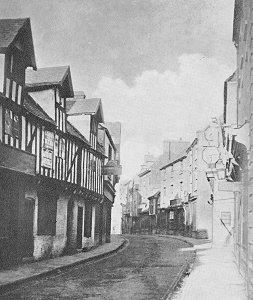

| On Taylor’s map,

at the eastern side of High Green is Lichfield Street. This ancient

street was originally called Kemstrete or Kempstrete, as stated in the

14th and 15th century Paget deeds. This name is

almost certainly derived from the medieval word for a “comb” and so is

another link with the wool trade. On the southern side of the street

stood Stirk’s Cooperage and the “Noah’s Ark” Inn where the early

Methodists met in a back room. Here they built the “Noah’s Ark Chapel”

in which John Wesley himself preached on a number of occasions, the last

being on 23rd

March, 1790. The proprietor at the time was William Horton who had

only been there for several months. In 1791 he advertised as a rum and

spirit dealer and became very active in the affairs of the town. His

niece was married to John Hargrove, who kept the “White Rose”, also in

Lichfield Street. On the northern side stood the Old Posthouse

and the “King of Prussia” Inn. |

Old Lichfield Street before demolition in the

late 1870s. |

|

In the Town Deeds the Inn is described as a burgage house, which

carried the right to a pew in St. Peter’s Church. It stood on the

site of what is believed to have been the medieval Guildhall where

the wool merchants would have met.

A look at Taylor’s map reveals that in those days Lichfield Street

ran into Horsefair (now Wulfruna Street) via the modern day

Lichfield Passage and it remained as such until the wholesale

demolition and widening of the street in the 1880s.

This is but a brief glimpse into the old town and

much more can be found in the records by anyone wishing to visit the

local archives. The records can, with a little imagination almost

bring the old town back to life, which can’t be done in any other

way.

Bibliography

History of Wolverhampton to the Early Nineteenth

Century, Gerald P. Mander, M.A., F.S.A. and Norman W. Tildesley,

Wolverhampton C.B. Corporation, 1960.

Wolverhampton. The Early Town and Its History,

John S. Roper, M.A., Wolverhampton, 1966.

A History of Wolverhampton, Chris Upton,

Phillimore & Co. Ltd., 1998.

|

|

Return to the

previous page |

|