|

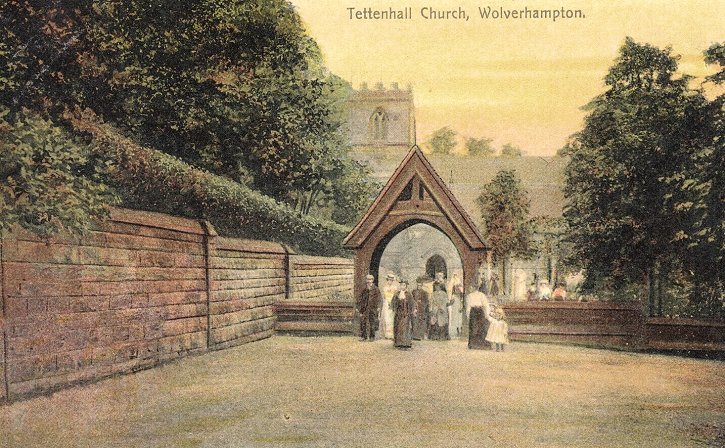

This is the story of St. Michael

and All Angels Church, Tettenhall as it was before the

devastating fire on the night of the 2nd February, 1950

when the building was badly damaged. All that remained

intact was the 14th century tower with its peal of eight bells,

and the Victorian porch. The church was rebuilt in

modern Gothic style, and consecrated on April 16th 1955.

A modern view of the church from

July 2010.

This article was serialised in the

September, October, and November 1906 editions of the

Wolverhampton Journal. The photographs were taken by the

author James P. Jones, who was known for his book "A

History of the Parish of Tettenhall, in the County of

Stafford" published in 1894 by Simpkin &

Marshall, of London.

From an old postcard.

Bev

Parker |

|

Tettenhall Church from its

picturesque situation, quite as much as from the beauty

of the building itself, possesses great attractions for

visitors to the pretty village. Of its origin we know

scarcely anything, but that a Church existed here in

early Saxon times is proved by a grant to the Dean and

Canons of Tettenhall by King Edgar, sometime between

A.D. 959-975.

This early Saxon Church would be

simple in form and construction, and would consist

mainly of a chancel and nave, with a low square tower of

two stages, the upper one containing only one bell. It

is probable there existed both side aisles, and two

smaller chancels, for a Collegiate Church, with a Dean

and five Prebendaries, even in those early clays of

Christian worship, would require a larger building than

is indicated by the above description. |

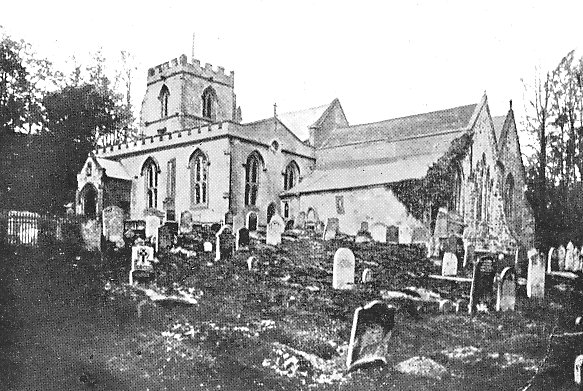

Tettenhall Church before restoration (1878).

|

The masonry of this early Church

would be of the rudest description, being simply rough

wattle and rubble, the windows would be merely slits in

the walls, splayed either way, a ready means of

affording the maximum of light, with the minimum of

interruption and aggression from outside. The building

would naturally be strongly built, as in those lawless

days when might was right, it would have to serve both

as church, and a place of refuge and defence, against

attack.

History and tradition afford no

clue to the founders of this midland church. There is

nothing to suggest who was the first apostle to preach

the gospel to the then pagan Saxons, and whose single

bell, calling over the waste marshes of the Smestow Valley, hastened the lagging feet of converts to the

shrine of St. Michael.

The Domesday Book, A.D. 1086,

contains the first recorded notice of Tettenhall Church.

It describes the possessions of the church at that date,

as returned by the Commissioners, and states that

Sampson, a chaplain of King William 1., was appointed

Dean of Tettenhall, and also of St. Peter's,

Wolverhampton. |

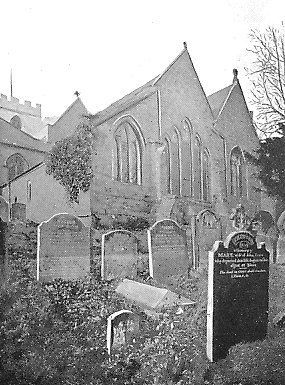

Tettenhall Church after restoration (1883).

|

It then appears again in the return

known as the “Taxatio Ecclesiastica Pope Nicholai IV.,”

which granted to Edward I. towards the expenses of a

crusade, for six years, the tenths of all ecclesiastical beneficies which had hitherto been paid to Rome. King Edward, probably to ensure his

getting the full value of these tenths, and perhaps with

a view to learn the actual value of the Church in

England, caused a valuation roll to be drawn up, which

was completed in A.D. 1291. In this return the yearly

value of the church is given as £29.6s.8d., and the

tenth thereof as £2.18s.8d.; four of the Prebends are put down in a

lump sum for £6.13s.4d.; while Pendeford Prebend is reported as owning land

at Tresull (Trysull) of the annual value of 10s. The record shows also, that

among its other possessions, the Church of Tettenhall

owned a Grange at Oaken, worth10s. annually, and another

Grange at Trescott, worth £1 annually. From these

figures it will be seen that the wealth of the

Collegiate Church of Tettenhall in A.D. 1291 was very

considerable. |

|

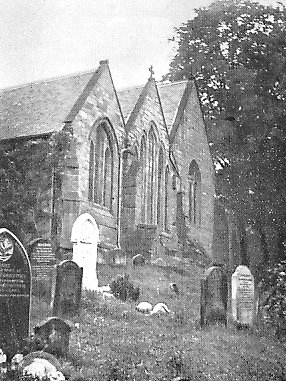

Tettenhall Church (east end)

before restoration. |

From this period until the “Valor

Ecclesiasticus" of Henry VIII., the value of the Church

is only occasionally referred to in local inquiries. In

A.D. 1377, an Inquiry into the possessions of a former

landowner in Tettenhall, brought to light the endowment

of Tettenhall Church.

A later Inquisition, temp

Henry IV., A.D. 1399-1413, on the estates of one Thomas

de Normanton, states as follows:

They (the jury) say that Edgar,

late King of England, gave and conceded to the Dean and

Canons of the Free Chapel of Tetunhal (Tettenhall) 100

acres of land, and 10 marks annual rent to help the

Church there, (viz., Tettenhall) for their own use, and

the use of their successors for ever, etc.

I have translated this from the old

contracted Latin of the Rolls, as this grant is

undoubtedly the endowment giving Tettenhall Church its

title of a "Royal Free Chapel." Unfortunately,

researches at the Record Office have failed to produce

the Inquisition above mentioned, but that it existed, is

proved by the fact that it appears in the large folio

"Calendar of Inquisitio ad quod damnum," officially

published in 1803. |

|

Next in importance in the record of

the church's history is the great known survey of Henry

VIII., as the "Valor Ecclesiasticus," A.D. 1535.

After

obtaining possession of all the property of the church

in England, and proclaiming himself its head, and

defender, King Henry sold the temporal and spiritua1

rights of these dissolved religious houses, to the

highest bidder.

Walter Wrottesley, Esq., as the largest

landowner in the parish of Tettenhall, was practically

compelled to purchase, in order to preclude the

interposition of strangers, who would have levied tithes

upon the whole of his estates.

The Crown exacted the full value of

the property, for Walter Wrottesley paid about twenty

two years purchase for it, which was much above the

value of freehold land at that date.

By this purchase

the whole of the spiritual and temporal rights of

Tettenhall Collegiate Church passed to the Wrottesley

family, who still retain them. |

Tettenhall Church (east end) after

restoration. |

|

Tettenhall Church tower (1894). |

There is little doubt that the

present building occupies the site of the earlier

edifices from which it has been evolved. For apart from

other considerations, the situation is one that would

readily commend itself to these early Christians as

being the most central and sheltered position in the

village community which had settled at Tettenhall.

Traces of the older buildings have been found at various

times during alteration to the Church, and Shaw, in his

History of Staffordshire, published in 1798, mentions

that portions of the old college buildings were still

visible to the east of the church.

The oldest fragment

of any previous church is to be found in the angle

formed by the tower and west wall of the main entrance,

it is a rudely carved slab, decorated on both sides and

probably formed the head of a window, or smaller opening

in the interior walls of the church. From the character

of the ornament I believe it to be a remnant of the old

Saxon church, and worthy of better preservation than its

present situation affords. |

| Of the present building, the east

end is the most ancient, being early XIII. Century. A

contrast between its present appearance, and as it

appeared after the enlargement in 1825, is interesting.

This enlargement and extension of the church in 1825,

was rendered necessary by the growth of the population

in the village, and to make room for the additional

south aisle as shown in the photograph, the whole of the

old XIV. Century south aisle, and the beautiful porch,

with its scriptorium over, was pulled down, and replaced

by a hideous imitation Gothic building, covered with

cheap plaster, while the south chancel, known as the

Pendeford Chapel, was covered with a low penthouse roof.

|

| When the Church was restored in 1883, these ugly

excrescences were removed and the present new south

aisle and porch of early English architecture was

erected. As will be seen from a comparison

of the two photographs of the east end of the church,

the gable end of the chancel, and the Pendeford Chapel

have both been lowered to their ancient pitch, as

indicated by the mason marks, and the east end of the

church has gained in dignity and impressiveness

externally. |

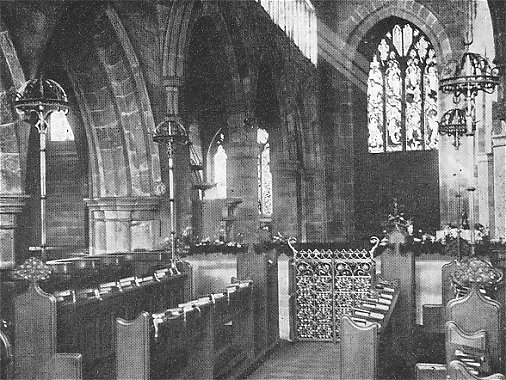

The chancel, looking west. |

|

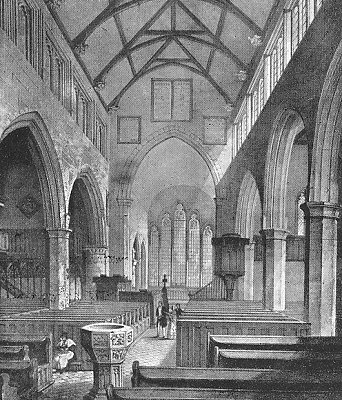

The interior of the church in

1844. |

The north aisle externally, with

the exception of the new doorway, giving entrance to the Wrottesley Chapel,

as now restored, is practically the same as when the original XIV. Century

builders finished it, excepting that originally there

was a doorway, now filled by a window, in direct line

with the porch.

Owing to a great landslip, rather more

than 150 years ago, this old doorway had to be closed

up. The tower is of the same date, and

has undergone little alteration, but the crocketed

pinnacles which originally terminated its four corners

have been destroyed.

The visitor to Tettenhall Church, entering by the

south porch, is at once impressed by the suggested

vastness of the building. The lofty nave with its

beautiful clerestory windows, the massive octagonal

piers supporting the nave, and the vista of arcades of

slender columns and arches looking eastwards, give the

observer more the impression of a cathedral than a

village church; while the dim religious light filtering

through the many coloured windows increases the feeling

of space and mystery. |

|

At either end of the nave you see

the "responds," which mark the extent of the old Norman

nave of the church; the pillars between are of a later

date, probably erected at the same period as the

building of the North Aisle, about A.D. 1350.

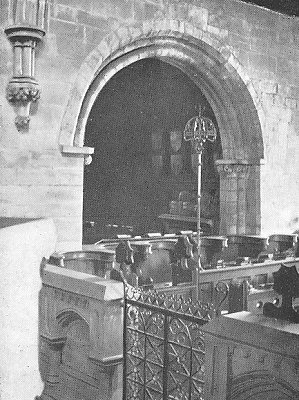

The transition arch leading from

the chancel to the Wrottesley Chapel is of earlier date,

and exhibits some curious features, it was probably

brought from another portion of the church at some

earlier restoration, as the appearance of the stonework

suggests that it has been inserted in the wall after

building.

The beautiful east window, with its

curious arcade of slender columns and decorated lancet

heads, is a pure example of early English work, probable

date about A.D. 1207. It is one of the most remarkable

windows of this period, and is almost unique. |

|

To this same period must be

assigned the north and south chancel arcade of arches,

which are very rich in decorative carving. A careful

inspection of these beautiful pillars will show that

these old workers did not slavishly copy each other, but

infused into their work a considerable variety of

design. In the angle formed by the pillars of the east

window and south chancel arcade will be seen an early

English piscina, in good preservation: the top

ornament was added at the restoration in 1883.

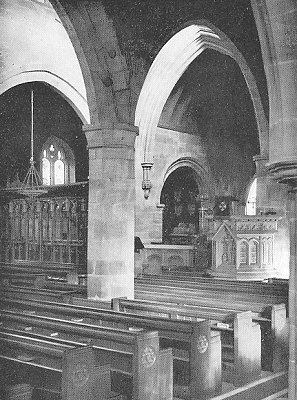

The view looking across the nave

gives a good impression of the massive yet simple

grandeur of the nave, and affords a glimpse of the

monuments in the Wrottesley Chapel. The beautiful carved

oak screen which shuts off the Wrottesley Chapel from

the main body of the church is of richly decorated

perpendicular work. Unfortunately, at the last

restoration of the church, much of the beauty of this

screen was ruined by careless handling. Originally it

had a groined canopy roof, which projected some distance

over the screen proper, the spandrils of which sprang

from the tops of the pillars supporting it and formed an

interlaced pattern of beautiful design, terminating in

the richly carved cornice above. A careful inspection of

the ornament of this screen will show that no two pieces

of ornament are alike. |

The transition arch in the

Wrottesley Chapel. |

|

Looking north eastwards across the

nave. |

In the Wrottesley Chapel are

preserved some interesting monuments to the Wrottesley

family. The oldest is an alabaster slate, with a

portrait of a man in armour and his wife, drawn in black

lines, at their feet sixteen children. It is to the

memory of Richard Wrottesley and his wife, and is dated

1417.

There is also a fine altar-tomb,

with effigies of John Wrottesley, Esq., and Elizabeth his wife, dated 1580, and

other interesting memorials of more modern date.

The armorial shields showing the

descent of the Wrottesley family are most interesting;

as is also the armorial window in this Chapel. The six

hatchments fitted in this window are formed of old

armorial glass, removed from Wrottesley Hall many years

ago.

The view of the nave looking west

gives a good impression of the lofty tower arch and the

great west window. This window was filled with stained

glass in 1860, and was the gift of the Ward family in

memory of their parents. |

| In the foreground of the picture

will be seen the ancient choir stalls. King Henry III.

granted six oaks from his forest to provide stalls for

the Canons of Tettenhall, and it is quite probable,

judging from the style and design of the carvings, that

the present stalls, or at least a portion of them, were

made at this period. The work on the "arms" of the

stalls is contemporary with the period. Under the seats

are some very good examples of "miserere"

carvings. The triple lancet window in the Fowler

Chancel is one of the purest examples existing, and is

of XII. Century date. |

|

The view of the nave, dated

1842, shows the church as it was after the enlargement

made in 1825, when the walls and ceilings were plastered

and white washed. In 1860 attempts were made at

restoring the church, and the disfiguring whitewash was

removed from the walls of the tower, and the great west

window restored to its original proportions; but it

remained for the restorers of 1883 to complete the

careful work of renovation which has resulted in the

present beautiful interior.

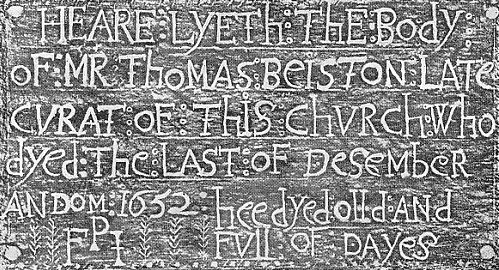

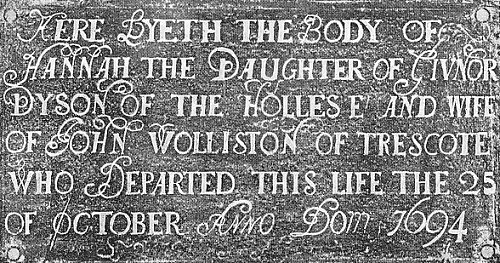

The curious memorial brass of the

Rev. Thomas Beeston, late Curate of this church, has

undergone some strange vicissitudes for, erected in

1652, it was used again in 1694 to serve as a memorial

to "Hannah Wollaston, of the Hollese, Prescott.”

What induced Hannah Wollaston's

husband to purloin this brass and use it as a memorial

for his wife's grave, I have no means of finding out,

but the fact remains that he did so. The brass was

reported by the Rev. S. Shaw, on his visit to the church

in 1797, as being "now lost." It was discovered again

during the restoration of the church in 1883, and is now

affixed to the east respond of the nave, near the

lectern, where the two inscriptions can be clearly seen.

|

The Cresswell Monument. |

| I shall have occasion to refer

again to the Beeston inscription, as I have good reason

to believe that it is the work of a forgotten artist in

metal and stone, whose other work in Tettenhall will be

described and illustrated in the concluding portion of

this history. |

An ancient lintel stone.

|

Tettenhall Farm, Upper Green. |

In the small window on the south

side of the Fowler Chancel is preserved all that is

left of the ancient stained glass which filled nearly

the whole of the windows of the church, but was

destroyed by zealous fanatics during the Puritan

revival. In the centre can be seen the head of a priest,

while underneath is an inscription as follows:

Orate pro anima Henrici Suthwyke,

pbd. Bobynhull.

"Pray for the soul of Henry

Southwick, Prebendary of Bobynhull, or Barnhurst."

This

Henry Southwick was Prebendary of the Barnhurst 1530,

when the Collegiate Church of Tettenhall was dissolved.

The portrait is of the same period, and probably a good

likeness of him.

The ancient stone font has been

restored (1842), but has some curiously carved panels of

Gothic design. Of ancient monuments in the Church,

beyond those already mentioned in the Wrottesley Chapel, there are very

few; but the fine mural memorial in the chancel to the

memory of Joan Cresswell, of the Barnhurst, is worthy of

inspection. It has an inscription in black letter, and

is dated 1590. |

| On the wall of the tower is still

preserved the memorial brass, with its quaint rhyming

epitaph to the memory of William Wollaston, of Trescott.

It has no date; but from evidences I have of the

Wollaston family it cannot be later than A.D. 1560.

Above it, will be seen the Fryer monument, in memory of

Richard Fryer, first M.P. for Wolverhampton. |

A monumental brass (front).

The rear of the monumental brass.

| This old brass was reported as

lost in Shaw's History of Staffordshire, 1797, but it

was discovered under the floor during the restoration of

the church in 1882, and when cleaned was found to have

an inscription on both sides. What induced John

Wollaston to appropriate the brass of the old curate,

and use it as a memorial to his own wife, is beyond me. |

|

The Church is exceptionally rich in

stained glass, all of which, with the exception of the

great west window and the heraldic window in the

Wrottesley Chapel, has been added since the restoration

of the Church in 1883, and in every case bears the name

of the donors.

In the vestry of the church can be

seen a curiously carved stone slab, which I shall

describe more fully in the concluding part.

Ancient Tympana

In all villages with any claim to

antiquity, there will occasionally he found vestiges of

ancient tympana or "lintel plates." The practice

of fixing a stone over the entrance doorway of houses,

bearing the initials of the owner and the date of the

building, sometimes the bare initials, but oftener with

curious symbolical carvings, and in the cases of

churches, with the figure of the patron saint in a

niche, dates from a very early period.

It can be traced back to the

elaborately carved symbols which ornament many a richly

decorated church doorway of Norman origin, when these

artists in stone were content to write their messages in

symbolic pictures, so that “he who runs may read,"

portraying in curved line and graceful scroll the

mysteries they would not perhaps dare not speak of

openly. The practice of this art as applied to dwelling

houses does not appear to date earlier than the

beginning of the 16th century, and was of a rude

character; yet the examples here shown, crude as they

are, exhibit a remarkable knowledge of Biblical history,

combined with originality of design.

The first example was discovered

under the floor of Tettenhall Church during the

restoration of that building in 1882, and is now

preserved in the vestry of the church; it is dated 1686.

This is one of the most curious lintel stones I have

ever met with. Within an elaborately carved border is a

rude carving of a man and woman, while in the centre is

a perfect "crux ansata," or "Tau Cross," between

representations of a palm, and the "sacred lotus" or

lily of the Egyptians. Unlike most other examples I have

seen, this bears no initial letters, but simply records

the message its original designer intended it to convey.

It would be interesting to trace the cutter of this

ancient stone with its mystic symbolism, for we have

here a curious mixture of Christian and pagan worship,

so remarkable as to suggest it is the work of a learned

and travelled brother of one of those great communities

who preserved inviolate the mysteries of their order,

handed down by tradition, and of rites and ceremonies they dare not reveal.

Another example, equally

interesting, and certainly the work of the same artist,

is to be seen on the gable wall of the farmhouse on the

Upper Green. It bears the same date, 1686, and has the

initial letters I.I.H. It is divided into eight panels,

within a decorated border; the first panel has a palm

leaf between the “crux ansata” and the Egyptian

lotus, then the initials, and the date follow. In the

lower half are two representations of a fig tree, with

what appears to be a wheel cross; and a point, within

three concentric circles. I have failed to trace an

owner of this house whose initials correspond to those

on the stone.

Another example, of the same

period, but less interesting, is over the doorway of "Gorsty

Hayes Manor House", it is a plain recessed oval, with

scrolls at the sides, bearing the initials W.S., and

dated 1683.

In some instances, more

particularly in the case of those entitled to bear arms,

a shield bearing the arms of the owner was placed over

the entrance porch of the house: as in the case of the

old Wightwick Manor House. While on houses of more

imposing design, such as Wrottesley Hall, Chillington

Hall, etc., the armorial bearings of the family filled

the pediment in the centre of the main front of the

building.

The artist who carved the two

lintels illustrated was also responsible for the

production of some ancient grave stones in Tettenhall

Churchyard, and for the memorial brass to the memory of

the Rev. T. Beiston, Curate of Tettenhall in 1682. From

this evidence it will be seen that this unknown and

forgotten artist was equally skilled in working in stone

and metal. The specimens of his work here illustrated

show a marked progression in execution and design, the

earlier attempts being crude, rudely cut figures, merely

incised lines scratched on the surface, while the later

examples exhibit a development of power and ability

unequalled in his earlier work. Examples of his work are

to be seen among the row of gravestones which border the

walk on the south side of the church, and again on the

north side, near the giant yew tree. |

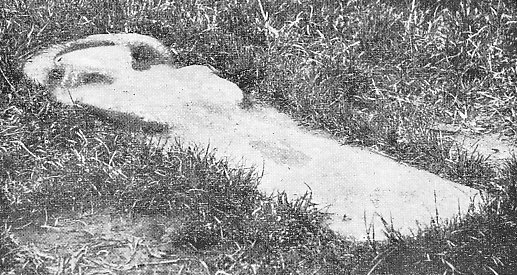

An ancient tombstone in the graveyard.

|

The Genesis of a Myth

“There are quaint stories told

of several gravestones in different parts of the County of Staffs.", Rev. G. S.

Tyack.

Under the south wall of the church

are some flat slabs, removed from the interior of the

church at the restoration, which are undoubtedly

memorials of former priests of the church. While others,

forming the covers of ancient stone coffins are to be

seen on the north side, near the walk under the yew

tree. These all bear representations of the cross, in

various simple and ornamental forms, clearly proving

they are priestly memorials. The same applies to the

timeworn effigy in the grass near the "Lime Tree Walk."

In connection with this effigy tradition has created a

story to account for its present mutilation. So long as

I can remember there has always been a tradition in

Tettenhall that this old gravestone is the effigy of a

certain wicked woman, who from her persistence in

spinning on Sundays, was punished by the loss of both

arms and legs. This story has invested this particular

stone with an interest and association for which there

is absolutely no foundation. I have investigated every

source of information likely to yield facts, but in

vain, there are no records of such an awful punishment

as the story describes, either in the parish records or

in the local records of the district.

In "Lore and Legend of the English

Church," page 98, the Rev. G. S. Tyack, B.A., gives the

following version of the legend:

In Tettenhall Churchyard.

Staffordshire, is a worn stone on which is carved a head

and body without limbs. Here the local chroniclers

relate, lies a woman who persisted in spinning on

Sundays. Having been severely reproved by her

neighbours, she promised to reform, and impiously wished

that, if she broke her promise, her arms and legs might

drop off. Old habits proved too strong for her, and one

Sunday she turned again to her wheel and set it

murmuring through the room, while she spun the twirling

threads, when, lo! her horrible wish was fulfilled and

she was in a moment reduced to helplessness.

Dr. Plot, who wrote a "History of

Staffordshire," in 1686, and was ever on the look out

for the marvellous in nature or history, makes no

mention of the stone or the legend, but he does tell in

all its gruesome detail, the horrible punishment which

befell one John Duncalf, who was horn at Codsall in

1655. In this story the points of detail are exactly the

same as those in the legend woven round this old stone,

i.e. bad habits, invoking God's judgment, and the

subsequent loss of both arms and legs. The only

difference being that in the legend the old woman

committed no worse a crime than spinning on Sundays,

while John Duncalf committed most of the crimes against

the Decalogue.

Shaw, in his History of

Staffordshire, Vol. II. p 230, prints in full the

history of this village reprobate, but makes no mention

of the stone at Tettenhall. But be does state that in

the churchyard at Tettenhall are some ancient monumental

figures lying buried in the grass, which formerly were

placed to the memory of some of the various members of

the collegiate church.

The stones which Shaw saw when be

visited the churchyard are still there, and a careful

inspection of this particular one will prove that it is

not the figure of a woman at all, but of a priest with

hands folded across the breast and clad in priestly

vestments. In the original photograph the arms are

distinctly shown, while the carving round the head

suggests the nimbus or symbol of his sacred

office. From the style of dress and carving I am

inclined to fix the date of this stone not later than

the end of the XIV. Century. It bas been sadly mutilated

by the careless feet of thousands who have been

attracted to it by the legend of the old woman whose

arms, dropped off, a story which has gained credence for

many years, but for which there is absolutely no

foundation in fact.

As the Rev. G. S. Tyack remarks,

"All these stories illustrate the tendency of the rustic

mind to explain everything about him 'somehow': let a

stone be never so quaintly carved, or strangely placed,

let it be the despair of antiquaries and its inscription

be a standing puzzle to the scholar, yet the local folk

will see no difficulty, but will have some legend

readily to hand which will fully account for

everything." |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|