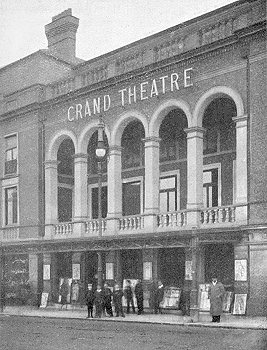

At the beginning of the twenty-first century Wolverhampton is rightly proud of the Grand Theatre - a wonderful example of a late nineteenth theatre completely refurbished to take its place in Wolverhampton's cultural life. Tremendous local pride was felt when the Grand opened way back on 10th December 1894, a pride that was recreated all over again 104 years later when it was re-opened after its restoration. The theatre enjoys a special position in the history of Black Country theatres, partly because of its own merits and partly because it is a sole survivor. This rather blinds us to the fascinating stories of many other local theatres that have vanished forever. Wulfrunians had already enjoyed many opportunities to be theatre-goers for over a century by the time the Grand opened but running a theatre in a town like Wolverhampton was a chancy business - audiences soon grew weary with what was offered and continually had to be tempted back to their seats with newer and better entertainment, or with vastly improved facilities provided at greater and greater expense. Nothing changes!

This plain brick hall tucked away behind the Swan was really Wolverhampton's first purpose built theatre and it lasted from 1779 to 1841. It was not used continuously during that time but was occupied by companies who would appear for a "season" - usually dictated by the duration of their theatrical licence. The law surrounding the granting of a theatre licence was complicated and attempted to distinguish between "drama" and "musical entertainment". In practice this led to some entrepreneurs adding songs, dances, juggling etc. to "drama" in order to avoid the need for a licence; while the providers of musical entertainment could be in trouble if they included a dialogue-based sketch in their show as this might be construed as being "drama". This confusion forms the background to the growth of two nineteenth century theatrical traditions. One tradition became concerned with the presentation of the drama on the stage itself, the other tradition treated what was happening on stage as something incidental to the business of selling drink: the "music hall" tradition.

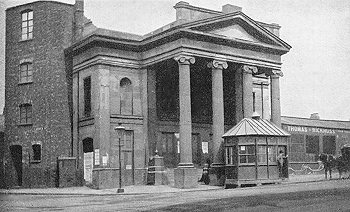

Bennett was one of those actor/manager characters who was equally at home playing the great tragedian on stage as he was at running the business side of things. He had established his reputation at the Swan and wealthy Wulfrunians turned out to support him while the theatre was new. However, within a few months audience figures declined and questions were raised about the economic viability of providing drama night after night on a permanent basis. The Theatre Royal, as this building was known, had a very chequered history with several periods of closure and changes of ownership and management. In the end it was put out of its misery by the very company that built the Grand. It was purchased with the intention of closing it, removing competition and focussing the future of drama at the Grand. It was demolished and the site was used by the Council to build Wolverhampton's Central Library.

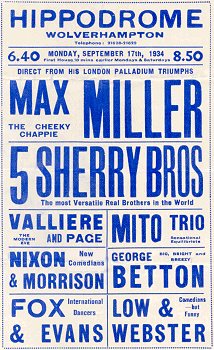

On 4th May 1863 The Prince of Wales opened in Bilston Street, styling itself as a "concert hall", basically providing the music hall type of entertainment in a fairly theatre-like setting. Such entertainment became increasingly popular with the wealthier artisan portion of the urban working classes - possibly at the expense of The Theatre Royal. The theatre in Bilston Street went through a number of refurbishments, some of which were virtually rebuilding programmes. It also changed hands a number of times. But the most confusing aspect of the theatre's history is a bewildering number of changes of name. Sometimes this was accompanied by a change in policy - sometimes moving towards the presentation of popular melodramas, sometimes back towards entertainment in music-hall style. In 1904 it adopted the name "Hippodrome" to convey the idea that the entertainment would be more circus-like, including equestrian acts.

The two competing theatres resolved their battle by working together from the end of 1906 onwards, leading to a situation where the Empire stuck to "variety" and the Bilston Street theatre, by then using the name Theatre Royal, returned to "melodrama". The choice of entertainment in Edwardian Wolverhampton was excellent. It was not even restricted to the three theatres described here. In 1909 the Pavilion opened in Tower Street providing a mixture of "variety" and cinematography. A year later cinemas began to open to concentrate on nothing but showing films, although no one at the time could have imagined that cinema might eventually threaten the existence of live theatres.

And that brings us back to where we began. Of all Wolverhampton's theatrical enterprises, the one that everyone knows is the one that has survived: the Grand. Three cheers for The Grand - but, as you can see, there is more to Wolverhampton's theatre history than just the story of The Grand. |