|

Inventive Genius in Electrical Engineering: ECC of Wolverhampton

Electric lighting was the wonder of the 1880s.

In a land dependent upon shimmering candles or dim gas flames to

cast a fluttering, hazy light over a small space, the ability of arc

lights to brightly illuminate a large area was astounding. And a

Wolverhampton firm was in the forefront of this technological

breakthrough. It was Elwell-Parker of Commercial Road which would

develop into one the most important manufacturing concerns in the

town - the Electric Construction Company. That it did so owed much

to the inventive genius of Thomas Parker, one of its partners. |

|

Thomas Parker in middle age. Courtesy of

Gail Tudor. |

In June 1888, a Manchester newspaper reported that "electric

lighting is rapidly establishing itself as a valuable

illuminating example". This had been made clear the previous

evening at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Old Trafford where the

great improvements which had been made "were shown by what was

undoubtedly a fine display of electric arc lighting", which lit

up the whole of the grounds. A total of 56 arc lamps had been

supplied by Edison and Swan, the business set up just five years

before by the pioneering and inventive Thomas Edison of the USA

and Joseph Swan of England. However the dynamos had been

especially made by Elwell-Parker. There were two machines which

were "shunt wound', each of which was capable of working 40 arc

lamps. Slow-speed machines, they ran at 700 revolutions per

minute.

It was a notable achievement for a company that had only been

founded in 1884 but it was one of a number of remarkable

successes. |

|

In January 1886 it was reported that 380

incandescent lamps had been installed throughout the Swan Garden

Ironworks of Messrs John Lysaght in Wolverhampton. The current

for them was generated by two Elwell-Parker dynamos which were

driven at 95 revolutions per minute by an ordinary high pressure

horizontal engine. A pair of similar dynamos had also been

supplied to the Monmore Ironworks of E. T. Wright and Sons and

at George Wilkinson's Sheet Mill at Tividale.

By now, Elwell-Parker had laid down the

electrical plant for the Blackpool Tramway, one of the earliest

examples of electric traction in the world. Then in late 1888,

and at the behest of Birmingham Corporation and the Birmingham

Tramway Company, the Wolverhampton firm played a crucial role in

the trials of an electric motor for tramcar propulsion in

Birmingham. The motor was made by Elwell Parker under a patent

from a Belgian company, but the necessary dynamo machine and

accumulators were manufactured according to the firm's own

patents. These trials led to the construction of the Birmingham

and Bournbrook Electric Tramway. |

|

Earlier that year the Wolverhampton

business had received a large order for dynamos, exciters,

secondary generators, regulators, metres, and other equipment

from a new company in South Kensington that aimed to replace gas

lighting with that of electric.

It was explained in a Sheffield newspaper

that the orders were valued at many thousands of pounds and that

other orders were expected quickly. Indeed "the works are very

busy, running day and night". |

One of the accumulator-powered Birmingham

trams. |

|

The rapid growth of Elwell-Parker arose

from its innovative and quality products arising from the mind

of the extraordinary Thomas Parker. The son of a moulder in

Coalbrookdale, he had been nine when he had started work at the

foundry where his father was employed. He later recalled that he

arrived at 5.30 in the morning "to light the fires, and so

prepare for the men. Sixty hours and more was the week's work .

. . Life was hard at the works. If a boy did not quickly do what

was ordered, he would often receive a kicking from his

superior."

From an early age, though, Thomas Parker

was determined to educate himself by attending evening classes,

whilst he also showed an aptitude for making things. After

becoming a moulder, he went to work in Birmingham. The

embodiment of a self-improving working-class man, he attended

the Church of the Saviour of the acclaimed preacher George

Dawson and went to lectures at the Birmingham and Midland

Institute.

Following his marriage to his wife, Jane,

and like many another highly-skilled men, Thomas tramped the

country seeking better employment opportunities. After a time in

the Potteries, he went to Manchester, where he also attended

science lectures at Hulme Town Hall. These were to have a

positive impact on his life. Thence he went to Dudley and

finally in 1867 he returned to Abraham Darby's Works at

Coalbrookdale as a foreman in the engineering section.

Now aged 24, he was rapidly promoted to

take charge of the chemical department and electro-depositing.

According to a local newspaper it was here that "his faculty for

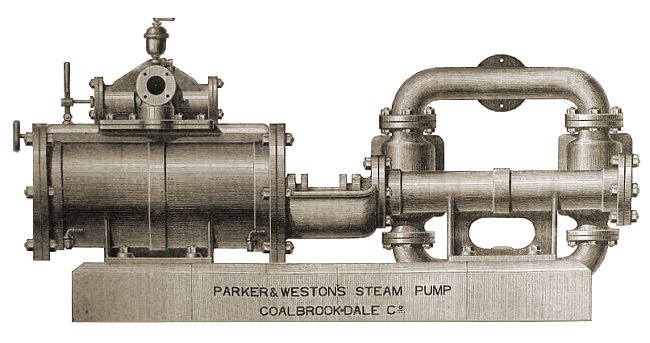

invention asserted itself". In 1877 he and Philip Weston, a

machinist at Coalbrookdale, patented improvements in direct

acting steam pumps and steam engines - for which they were later

awarded a medal at the Inventions Exhibition. |

|

A Parker and Weston steam pump. |

|

Two years later, Thomas designed and built

a dynamo for the electro-plating department at Coalbrookdale and

he went on to invent the open Kyrle grate and the Robinson gas

engine for Tangye's of Smethwick. But henceforth it was

electricity which gained the attention of his quick and talented

mind. By 1882 Thomas was on the management of the engineering

portion of the foundry and that year he gave a lecture in which

he demonstrated Edison incandescent lamps. The source for the

current was secondary batteries made by Parker. In their

manufacture he had "discovered and utilised the important point

of the great value of concentrated nitric acid in facilitating

the formation of the necessary oxide". He applied for a patent

for this discovery at the same time as Garton Plante and the

patent was divided between them.

That year, Parker also became involved with

Paul Bedford Elwell of the Patent Tip and Horseshoe Company in

Commercial Road, Wolverhampton and next to the Crown Nail

Company. Elwell had been educated at King's College, London,

where he had obtained a distinction in mathematics, and he had

studied coal mining and iron manufacturing in northern France.

He also had an inventive bent and had taken out patents for

venetian blinds and nail making machinery. Together Elwell and

Parker patented an improved lead-acid accumulator and

improvements in dynamos and electric lighting apparatus.

At the end of 1882, Parker moved to

Wolverhampton and the two men joined forces. With 100 people

working in Elwell's operation making nails and horseshoes,

Parker started his side of things with one of his sons and one

man. At first they built accumulators but early the next year

they made a dynamo. Parker himself thought it was a 'waster',

but it was bought by a representative of the Edison and Swan

Company of Manchester who had visited the works. After some

attention on site by Parker, it was successful in coating calico

printing rollers with nickel.

The inventor remembered that he received a

£40 and a testimonial. He was encouraged to build a dynamo for

lighting, and "this was a success, and got us an order for six.

We received from the Manchester Edison Company of that time,

£1,000 in advance for building dynamos: this was the beginning

of Elwell-Parker, and of dynamo manufacturing at Wolverhampton."

This business developed rapidly and in

December 1884 the company of Elwell-Parker Ltd was formed with a

capital of £50,000. Interestingly the move gained more attention

in the Manchester newspapers. This was because of the connection

with Edison and Swan and because all seven subscribers were

Manchester men. |

|

From 'The Engineer'. |

|

Parker was now gaining considerable notice

and acclaim. In 1885 he was made a member of the Institution of

Electrical Engineers and was praised in the Royal Society of

Arts Journal for leading the way in developing the electricity

industry in Britain. His ingenuity was highlighted two years

later when he developed a cheaper process to extract phosphorus

and chlorate of soda by electrolysis.

By now, Paul Bedford Elwell had left for

Paris to prepare plans for its underground electric railway but

Parker continued to direct the growth of the Wolverhampton

company. In 1889 he was made a member of the Institute of Civil

Engineers, whilst Elwell-Parker Ltd, which now employed 400

people, was taken over by the Electric Construction Corporation

Ltd. Parker was appointed engineer and manager and under his

supervision an impressive new factory at Bushbury was designed,

laid out and constructed. This included a large electrical

'Erecting Shop' which housed two tracks running 30 ton cranes.

Parker went on to direct numerous "very

large installations in connection with electric traction,

including the Liverpool Overhead Railway and the overhead system

of the electric traction in South Staffordshire". The

installation of electrical lighting in Oxford was also designed

by Parker and this 'Oxford System' was adopted by other towns.

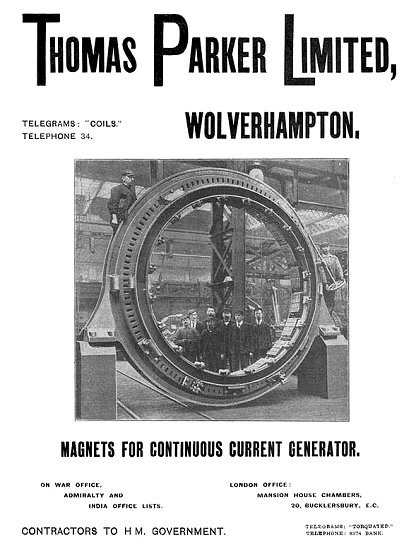

In 1894, Parker ended his association with

the ECC and set up Thomas Parker Ltd to manufacturing plant for

electric lighting, electric transmission of power, electric

railways, electric tramways, and electro-chemical and

electro-metallurgical purposes amongst other things. The three

other directors were Charles Tertius Mander, the Mayor of

Wolverhampton; Thomas Graham, the proprietor of the 'Express &

Star'; and William Thomas, a manufacturer. |

|

A 1905 advert from 'The Electrical

Review'. |

Production was at a new works on the

Wednesfield Road. The company was awarded a gold medal for

high-speed railway motors at the International Exhibition in

Brussels in 1897.

That year Parker's initiative led to the

formation of the Midland Electric Corporation to distribute

electricity in South Staffordshire. It was the first company to

get statutory powers to distribute electricity over such a wide

area. A power station was built at Ocker Hill with sub-stations

at Bilston, Brierley Hill, Darlaston, Old Hill, Tipton and

Wednesbury.

In 1899 Parker stepped down as managing

director of Thomas Parker Ltd. However, he remained on the board

and as consulting engineer until 1904 when he moved to London,

where he was consulting engineer to the Metropolitan Railway

Company. As such he was responsible for the design and

construction of its first electric engine.

When he died in December 1915, Thomas

Parker was acclaimed as a pioneer of electrical railways and as

one of those responsible for the progress made in electrical

science in the latter part of the nineteenth century. |

|

As for the Wolverhampton companies with

which he had been associated, unfortunately it seemed that there

was not enough business nationally for two large electrical

engineering firms to prosper in one town and in 1909 Thomas

Parker Ltd was wound up.

The Electric Construction Corporation had

also struggled after a bright start. In 1893 it too had been

wound up, but fortunately it was reconstituted as the Electric

Construction Company. It then prospered. During the 1930s and

40s its main production was in rotating electrical machinery,

switch and control gear, static transformers, and rectifiers;

and by the 1960s it was also manufacturing and installing many

of the power station generator systems in the UK.

By this decade the firm boasted several

factories in Wolverhampton and abroad. Locally, a control gear

factory had been built at Shaw Road, by the main works; whilst

the associate companies of E.C.C. Moulded Breakers Limited and

Federal Electric Limited had been set up in Fordhouse Road,

Bushbury. These made a complete range of medium voltage

switchgear for use in electrical distribution in industry,

hospitals, shops and houses. |

|

|

In the late 1970s a policy decision was

made to concentrate all the production effort onto the range of

Brushless A.C. Generators and the 'Automatic Voltage Regulation'

system. These generators were produced in large quantity and

supplied worldwide to diesel set manufacturers such as Lister,

Blackstones, and Petter but in 1983, despite efforts to redesign

the machine, which unfortunately lacked capitalisation, cost

effective competition began eating into the market.

Employing about 2,300 people at its peak,

E.C.C. was of massive importance to the economic well-being of

Wolverhampton, but by the end of the 1960s it was beginning to

face problems. In particular, cheaper foreign products, some of

them subsidised by governments, had an adverse effect upon

sales. These problems mounted and sadly the E.C.C. factory at

Showell Road, Bushbury was closed in 1985 and 800 people lost

their livelihoods. It is a pity that today, too few realise the

importance of this site and of Wolverhampton to the emergence

and development of electrical engineering.

However the company lives on through former

employees who meet at the 'ECC Social Club' in Showell Road,

Bushbury. Since 1985 a well-supported reunion has been held each

October, bringing together old friends and companions. Details

are available via tetlow620@btinternet.com or rogben@blueyonder.co.uk |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|

|