|

|

|

The town stands on the edge of the

South Staffordshire coalfield, next to the Wenlock

limestone and shale that forms the high ground in

Dudley. It quickly falls away and underlies the coal

measures which in places are several hundred feet deep.

The layers of coal are separated by layers of sandstone

and shale that lie on an irregular, undulating surface,

so their depth varies considerably. There was also a

layer of fire clay and some surface deposits of clay

from the last ice age, which were both used for brick

making. The coal layers varied in thickness and had

several names. There was the Brooch Coal, often about

four feet thick; the Thick Coal, up to about 30 feet

thick; the Bottom Coal and in places the Heathen Coal,

both a few feet thick, and also some ironstone.

The coal mines greatly prospered

with the opening of the canal network in the 1770s,

which allowed large amounts of coal to be easily and

cheaply transported for the first time. The building of

local railways in the 1850s also helped the local

industry, but to a lesser extent.

|

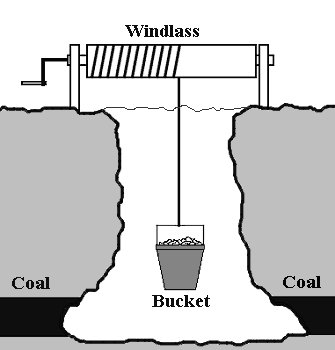

| In places where the coal was close to the surface,

bell pits were dug. They were just an unsupported shaft

around 20 to 25 feet deep, which was widened at the

bottom to remove as much coal as possible. This

continued until the shaft was in danger of collapsing.

The pit was then abandoned and a new one dug nearby.

People were lowered into the shaft, and the spoil

removed by a bucket that was wound up and down the shaft

by a windlass.

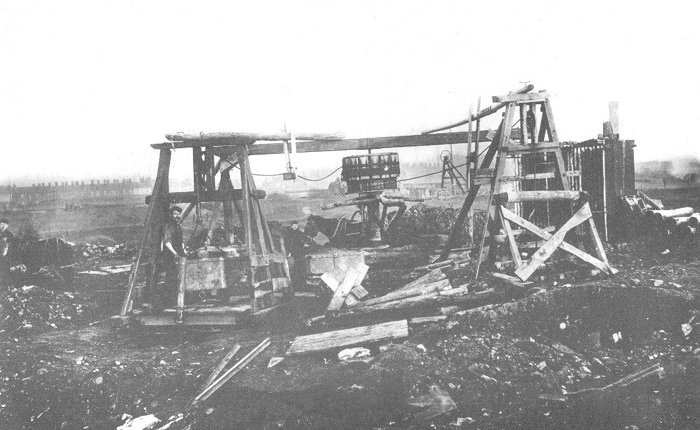

The larger mines, the deep mines, often

used a horse gin to lower the miners and raise the

spoil. They were sometimes several hundred feet deep.

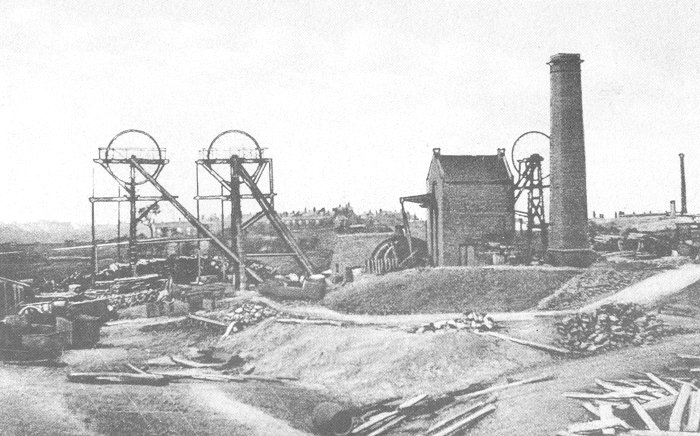

Some of them, particularly the deeper ones had a steam

engine to raise or lower a cage and to pump out flood

water, which was always a problem. |

A typical bell pit. |

A gin pit, showing the horse and the gin. From

an old postcard.

The horse gin that's on display at the Museum of

Science and Industry in Manchester.

|

In 1712 a Newcomen steam pumping

engine began to operate at the Coneygree coal mine and

the first commercial steam engine built by Boulton and

Watt began pumping water from Bentley and Company’s

Bloomfield Colliery in 1776.

There was a huge demand for coal to

fuel the local iron works and so large numbers of coal

mines operated in and around Tipton. Some of the blast

furnaces consumed 600 tons of coal per week. Mine spoil

heaps became a common sight. Thanks to the canals it was

a relatively cheap and easy matter to transport coal to

countless industries in the Black Country and

Birmingham. By 1835 the annual rent for coal mining land

was around £1,000 an acre.

In the 1870s things started to go

wrong. A depression in the iron trade led to a fall in

the price of coal, which in turn led to the closure of

many mines. A long strike took place in the coalfield,

during which labour was withdrawn. Pumping engines were

not operated, and many mines flooded. In 1870 it was

estimated that around 150 million tons of coal, and 20

million tons of iron ore were under water in South

Staffordshire.

Some mine owners would not use a pumping engine because

they were also draining their neighbour’s pit at their

own expense. Pumping also altered surface drainage,

because the water was run into streams, which percolated

back into the mines. |

A local pit with a steam-powered hoist and

water pump. From an old postcard.

|

A petition to Parliament led to the

South Staffordshire Drainage Act of 1873. Under the

terms of the act, a Board of Commissioners was created

to raise money to fund pumping operations. A rate of one

penny per ton of coal, slack, and fire clay was levied

on the mine owners, but initially little progress was

made. In 1878 greater powers were granted to the

commissioners. During the next 10 years, £100,000 was

spent on pumping water out of the deeper mines. In 1886

the levy was raised to nine pence per ton of coal, slack

and iron ore, three pence per ton of fire clay, with an

addition of one penny per ton for surface drainage.

Water courses were straightened, and made watertight by puddling the beds with clay.

The Mines Drainage Commission

opened a pumping station off Moat Road, Summer Hill, on

part of the Moat Colliery site. It was powered by a

large beam engine that could pump water from a depth of

620 feet. The engine operated between 1893 and 1902 and

raised over 7.3 billion gallons of water during that

time. The operation cost over £2,500 annually, but in

spite of all the efforts, the drainage problem was never

solved. The Commission was largely ineffective. |

Working at the coal face. From an old

postcard.

|

Coal mines were dangerous places in

which to work. There were many accidents, some resulting

in fatalities. Underground gases such as methane

accumulated in pockets in the coal and adjacent strata.

The gases, known as firedamp, were flammable and could

easily explode. In 1849, an explosion at Moat Colliery

caused around twenty deaths (the exact number is

uncertain). There were 62 survivors. When mining

fatalities occurred, it was customary for the employer

to pay for a coffin and pay burial fees. Injured miners

usually received a coal allowance during their time off

work. Some of the local mines, including Horseley

Colliery, gave gifts of coal to the local hospitals that

looked after injured miners.

In 1890 the Mines Drainage

Commission wanted to know if it was still worth draining

mines in the South Staffordshire Coalfield and so

contacted mine owners to ask for an estimate of the

quantity of workable coal still in the ground. The

results showed that in the Tipton area alone, around 43

million tons of workable coal and ironstone were still

in the ground. By that time coal production had fallen

to half of what it was in 1874, and around £75,000 would

be required to completely drain the deep pits in the

area.

In 1896, W. Beattie Scott, H.M.

Inspector of mines for the South Staffordshire District,

compiled a list of working mines. The mines in Tipton

were as follows: |

|

Name |

Owner &

Address |

Manager |

Under

Manager |

Underground

Workers |

Surface

Workers |

Minerals

Worked |

|

Bunn’s Lane |

Joseph Marsh,

Dixon’s Green, Dudley |

|

|

6 |

2 |

household

coal |

|

Coneygre (part) |

Wilkinson &

Vaughan, Park Lane, Tipton |

|

|

9 |

4 |

coal and ironstone |

|

Coneygre (part) |

J. Kirkham,

Coneygre, Tipton |

|

|

10 |

4 |

coal and ironstone |

|

Coneygre (part) |

J. and S.

Baggott, Sedgley Road, Tipton |

|

|

5 |

2 |

fireclay |

|

Coseley Moor |

Wones Brothers,

Coseley Moor, Tipton |

A. P. Taft |

|

36 |

7 |

manufacturing coal |

|

Foxyards (part) |

G. G. Wilkinson

& Co., Foxyards, Dudley |

|

|

11 |

4 |

coal and fireclay |

|

Foxyards (part) |

G. Powell,

Foxyards, Dudley |

|

|

2 |

2 |

manufacturing coal |

|

Foxyards (part) |

Flavell

Brothers, Foxyards, Dudley |

|

|

3 |

2 |

manufacturing coal |

|

Foxyards and

Rounds Hill |

The Earl of

Dudley Priory Offices, Dudley. Gilbert

Claughton agent |

A. W. Grazebrook |

H. Rickward |

276 |

97 |

cement-stone, coal,

ironstone, fireclay |

|

Gospel Oak |

Gospel Oak

Colliery Co., Dudley |

C. A. Clarke |

V. A. Wilks |

191 |

36 |

coal, ironstone, pyrites |

|

Gospel Oak

(part) |

William

Barnbrook, Great Bridge |

|

|

6 |

4 |

household

coal |

|

Groveland |

Joseph Marsh &

Sons, Kate's Hill, Dudley |

|

|

9 |

3 |

manufacturing coal |

|

Horseley (part) |

Thomas

Fieldhouse, Horseley, Tipton |

T. Roper |

T. Fieldhouse |

12 |

4 |

coal, ironstone, pyrites |

|

Horseley (part) |

W. J. Hayward &

Co., Horseley, Tipton |

C. A. Clarke |

Luke Roberts |

102 |

19 |

coal, ironstone, pyrites |

|

Hurst Lane |

Hurst Lane

Colliery Co., Tipton |

|

|

22 |

5 |

coal and ironstone |

|

Jubilee |

Joseph Marsh,

Tividale, Tipton |

|

|

|

|

manufacturing coal |

|

Moat |

Mines Drainage

Commission, Trindle, Dudley |

E. Howl, Agent |

|

|

|

pumping

station |

|

Moat |

Moat Colliery

Co., Tipton Moat, Tipton |

Thomas Roper |

W. Tudor |

54 |

15 |

manufacturing coal |

|

Moat |

Ben Southan &

Son, Tipton Moat, Tipton |

|

|

12 |

5 |

Abandoned |

|

Park Lane

(part) |

George Wellings,

Park Lane, Tipton |

|

|

6 |

2 |

manufacturing coal |

|

Wednesbury Oak |

Phillip

Williams & Sons, Wednesbury Oak, Tipton |

A. Wilks |

E. Bowen |

284 |

59 |

coal and ironstone |

| |

|

Number of workers |

1,056 |

276 |

|

|

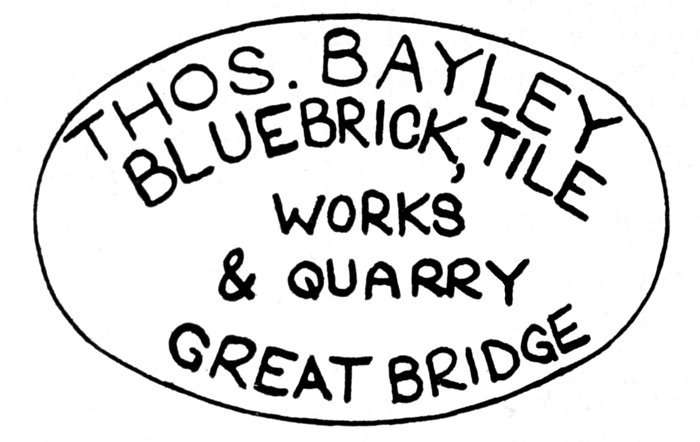

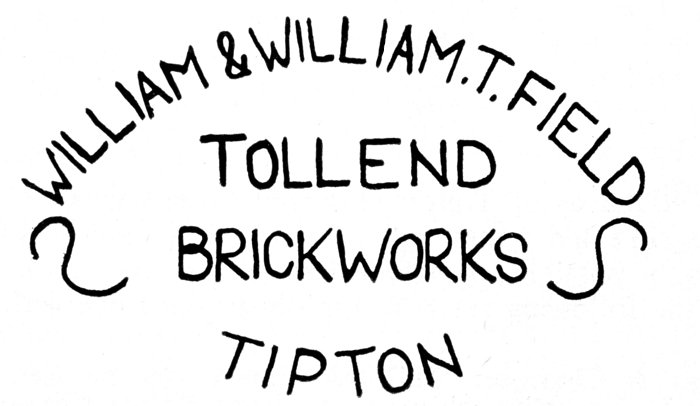

| By 1896 most of the local collieries had closed,

although a few of the larger ones remained, bringing the

total mining workforce to 1,332. By this time, most of

the easily workable coal had gone, and within 25 years

so had the local mining industry. Some mines, such as

the Toll End Colliery Company, run by William and

William T. Field, used the local clay deposits to

produce bricks. They were producing bricks before 1864.

One successful brick maker was Thomas Bayley, whose

family ran the Great Bridge Brickworks, at Golds Hill,

for at least 80 years. Bricks were still made there in

1932.

Trade Mark.

Trade Mark. |

|

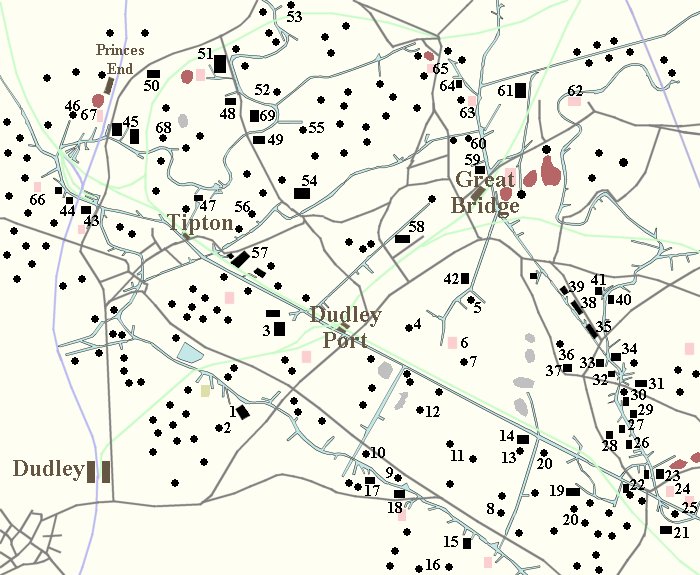

|

|

1. |

|

Coneygre Furnaces |

24. |

Albion Brick &

Tile Works |

47. |

Tipton Green

Furnaces |

|

2. |

|

Coneygre

Colliery |

25. |

Piercy Brick

Works |

48. |

Summer Hill

Works |

|

3. |

|

Wellington Works |

26. |

Vulcan Foundry |

49. |

Hope Works |

|

4. |

|

Denbigh Hall

Colliery |

27. |

Vulcan Tube

Works |

50. |

Tibbington

Foundry |

|

5. |

|

Cophall Colliery |

28. |

Brush Farm

Ironworks |

51. |

Gospel Oak

Works |

|

6. |

|

Pumphouse Brick

Works |

29. |

Nelson Ironworks |

52. |

Moat

Colliery |

|

7. |

|

Pumphouse

Colliery |

30. |

Woodlane

Ironworks |

53. |

Schoolfield

Colliery |

|

8. |

|

Peartree Pit |

31. |

Royal Eagle Tube

Works |

54. |

Horseley

Furnaces |

|

9. |

|

Victoria

Colliery |

32. |

Eagle Ironworks |

55. |

Hope

Colliery |

|

10. |

|

Hullbridge

Colliery |

33. |

Staffordshire

Works |

56. |

Horseley

Colliery |

|

11. |

|

Waterloo

Colliery |

34. |

Ryders Green Tar

Works |

57. |

Gas Works |

|

12. |

|

Groveland

Colliery |

35. |

Atlas Ironworks |

58. |

Horseley

Ironworks |

|

13. |

|

New England

Colliery |

36. |

Whitehall

Colliery |

59. |

Great Bridge

Iron & Steel

Works |

|

14. |

|

Bradeshall

Furnaces |

37. |

Dunkirk Foundry |

60. |

Eagle

Colliery |

|

15. |

|

Hange Furnaces |

38. |

Dunkirk

Ironworks |

61. |

Golds Hill

Ironworks |

|

16. |

|

Hange Colliery |

39. |

Nelson Foundry |

62. |

Golds Green

Brick Works |

|

17. |

|

Tividale Sheet

Mills |

40. |

Ryders Green

Tool Works |

63. |

Crownmeadow

Colliery & Brick

Works |

|

18. |

|

Etna Iron Works |

41. |

Crown Bridge

Works |

64. |

Crown Iron

Works |

|

19. |

|

Union Furnaces |

42. |

Sheepwash

Ironworks |

65. |

Toll End

Blue Brick Works |

|

20. |

|

Union Colliery |

43. |

Tipton Hall

Works |

66. |

Foxyards

Fire Brick Works |

|

21. |

|

Izons Foundry |

44. |

Coseley Moor

Furnaces |

67. |

Bloomfield

Brickworks |

|

22. |

|

Gas Works |

45. |

Bloomfield

Ironworks |

68. |

Tibbington

Colliery |

|

23. |

|

Albion Ironworks |

46. |

Roundhill

Colliery |

69. |

Mines

Drainage Pumping

Station |

|

|

|

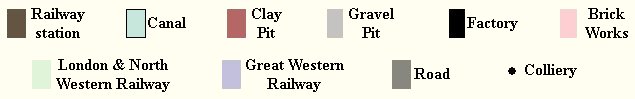

Ironworks and coal mines in the 1880s. |

|

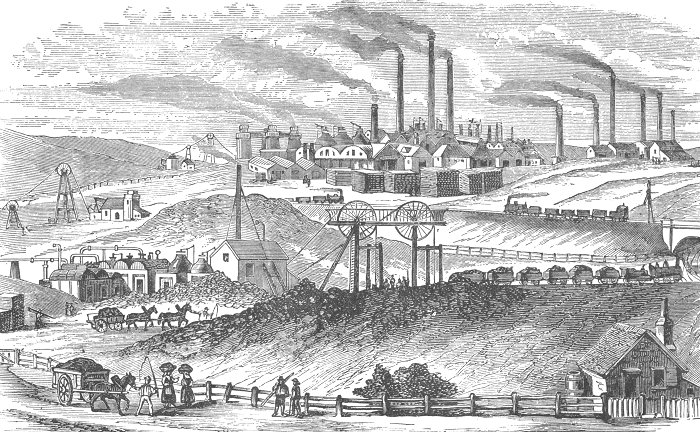

The

industrial scene in the middle

of the 19th century. A mixture

of coal mines and ironworks. |

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|