|

My Early Years

I was born on 17th January 1924 at

the Kings Arms public house in Princes End, Tipton, the

first of three boys. At that time, my grandmother, Alice

Preston, was the licensee. My father, Harold Smith,

worked at a factory as a supervisor, but at night he

helped in the pub. They inform me that when I was born I

was the ugliest baby that anyone had seen. My next door

neighbour tells me that I have not changed much!

I kept them awake at night, so one

night my father took the top off a bottle of milk, put a

teat on the end, and left it in the cot. I drank the lot

and slept for 24 hours. My grandmother said that he had

killed me, but that they had had the best night's sleep

since I was born.

The choice of names is not very

clear. My father chose Stanley and they wanted another

name as well. Whether by accident or design, my mother's

youngest sister, Nance, was sitting on the old night

soil toilet, which was down the garden, when she came

running down shouting that she had thought of another

name: 'Bertram'. It was decided: 'Stanley Bertram

Smith'. So why 'Tony'? Well, that will be explained

later on. |

|

Me, Tom, Bob, Reg and Frank. |

I will now jump forward four years

to when my brother Reg was born. You do not remember too

many facts, but I always thought that I had three

mothers and one father. The reason I thought this was

because the house was my grandmother's. Mum and Dad and

my Aunt Nance, my mother's youngest sister, would tell

me to do this, grandmother would come out and ask why

was I doing this, then Mother would tell me to do

something else. Confused?

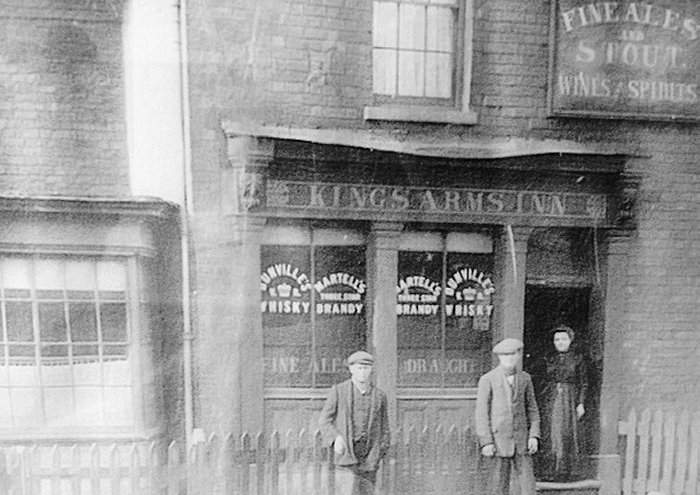

In the local paper they have a

photograph of the old pub and with it is grandmother and

two of the old customers. When I began to understand the

layout of the pub, you never saw any ladies in, only

men. Ladies only started coming in later on. There was

sawdust on the floors, iron tables, and spittoons under

the tables. The men used to spit in these from a good

distance.

The main room was called the 'Tap

Room'. I still have not learned why this was the case.

In the middle of the Tap Room stood a coke burning stove

and after the men had left at night, around 11 or 12pm,

we would take a shovel and bring the coke out of the

stove and put it on our fire in the kitchen. Then we

would grill beef steaks over the fire on a wire grill.

The last one was wonderful. On my 5th birthday I started

school. This was next to the public house. I think I

must have been the quickest youngster to be sent home.

They sent me home because they found me kissing a young

girl in the playground. |

|

At about six years old we were

allowed to attend the local cinema known as the 'Flea

Pen'. I would go with my cousin Tom who was twelve

months older than me. The films we liked were cowboys

and indians and this was how my nickname 'Tony' was

thought up. In one of the long-running films there was a

cowboy and his horse: Tom Mix and Tony', we would go

back home taking off these two. One of the customers in

the pub saw us and started calling me Tony. That is how

I got the name and now no one since that time has used

my real one.

In the cinema they had long wooden

benches and when it got too busy, the owner would come

along with a long bamboo pole, tap you on the head and

ask you to move closer. We did not mind this, but some

of the men would come straight from work, bringing their

sandwiches with them, usually it was bread and cheese

with onions.

On the 23rd May, 1931, Frank, my

youngest brother, was born. The world has changed a lot

since we were young, but not for the better. There were

no televisions, only radio and these were run on

batteries and accumulators. You had to take them to be

charged. There could be as many as six or more of these

and only people with money could afford them. The young

children didn't swear as they do today. Most houses left

their doors open and you felt safe. Some of these

ordinary folk would make stone ginger beer, or it cost

you one penny a bottle. You could speak to most people

without being afraid.

The churches were our centre of

social entertainment and Milk Bars where we went for

drinks and a chat. Most houses had what we called 'the

brew house'. This was attached to the dining room and

had the cooking stove and the boiler for washing

clothes, nearly always done on a Monday morning. The hot

water in the boiler was also used for baths. Our bath

was a metal one and could be carried around the 'brew

house'. It was very cold so you tried not to have many

baths. There were no washing machines, so every Monday

women would boil the clothes and then you would hear

them thumping the clothes with a wooden dolly in a

wooden tub. The main transport was by horse and trap or

trams. To go ten to twenty miles was like going fifty to

a hundred miles today.

My grandmother was one of the first

ladies to hold a pub licence and she was very strict

with the customers as they were big drinkers, employed

mainly in the steel works. Rules were laid down so that

they could play dominoes, but no cards. This came about

because four men were playing one day and an argument

started, one of the men took his boots off and threw

them at the other man. The boots missed him and went

through the window, so no more games of cards. They

still tried to cheat, even at dominoes. We kept four

boxes of them behind the bar and the way they would

cheat was by marking the double sixes. If the men found

one marked they would put them back in the box, stick

them in the stove and ask for another box.

|

|

The Kings Arms. Standing in

the doorway is licensee, Alice Preston. |

|

There are a lot of stories I could

tell as regards the customers, but there is one that

comes to mind. Grandmother ran a Christmas club. The

customers saved all year then just before Christmas we

would pay it out with the interest they had made. This

one Christmas I was helping Grandmother put the money in

the little bags when who should come in but Nelly Hill.

Nelly was about twenty years old.

Her mother had died and she lived alone with her father

whose nickname was Honky Hill. I assume it was because

of his big nose. As Nelly picked up her packet my

grandmother said "I like your new hair perm, Nelly", and

she said thank you Mrs Preston and left. When we had

cleared the money we went back into the bar and

grandmother spoke to Honky Hill about his daughter's

hair. She said "Honky, I like your daughter's hair, but

why didn't she wash her face?" He said that she had done

because when he was in the kitchen, he saw her washing

the crockery and then she washed her face in the water.

That's what you call conserving water; even in those

days!

When my youngest brother was born,

everything got a bit crowded in the pub, so my father

decided to move into a house in Salter Road. It was not

too far away from the pub. I still remember walking back

at night, Frank in the pram, Reg sitting on top, and me

walking by the side. About this time I moved up to the

Princes End School.

I was very lucky because my cousin,

Doreen, sat by me at the back of the class and she was

very bright. She was an only child and her mother was a

teacher. My luck ran out when the headmaster took our

class in an exam. We had to take the exam papers to him

to mark. He marked Doreen's 'very good' but when I took

mine to him he put a cross through it and threw my paper

to the back of the class. I think he thought I had been

copying, as if I would! I am not going to say whether I

did copy or not. The only thing I will say is that she

became a headmistress. |

|

When you look back, I think my

generation had the best of both worlds. Before World War

One there were the Victorians. My grandmother was sent

away into service at the age of fourteen. My grandfather

was working in a factory at the same age. There was no

television or radio and young people had to make their

own entertainment: marbles, skipping etc.

After 1924 things began to get

different, more relaxed, but not enough to let children

and teenagers get out of hand. Mind you, my English

master would tell us that he felt sorry for us because

we were born in a nervous time, just after the First

World War, 1914 - 1918.

The one thing at that time was that

you did not grow too old too quickly. Sex was a bit more

reserved and not many girls got into trouble as it was

frowned upon. If a girl did get pregnant she was sent

away to her auntie's to have the child.

My Aunt Nance, who lived at the pub

with us before she got married, died in 1996 at the age

of 93. Just before she passed away I was able to ask her

if some of the stories I had been told were true. She

said they were, and they did happen. |

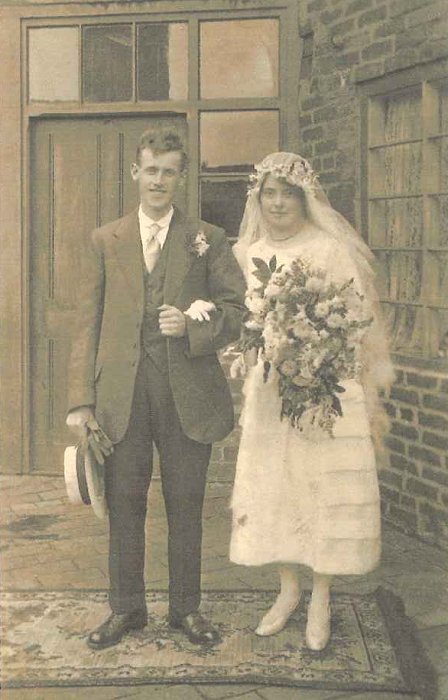

My mother and father at the back

of the pub. |

|

On a Saturday night we would cut up

loaves of bread, butter it, and then make sandwiches for

the men on Sunday, all free. I could never understand

how they went home on Sunday and ate their dinners.

George Ashfield, one of our old Boar War customers (you

could always tell them because they had large beards),

was a heavy drinker. The story goes that his wife was

cooking his dinner when the plate slipped and it went on

the floor. She went into a panic because he kept to a

set time and would be very nasty if it was not on the

table. When the bell rang she had to think what to do

and luckily George was not too drunk so she told him to

go into the front room and his dinner would be about

five minutes.

The gods must have been with her,

because he went to sleep in his rocking chair. When he

had gone off she had a brain wave. She put her finger in

the gravy and very gently, so as not to wake him,

smeared the gravy on his beard. He was only asleep for

about five minutes and woke up angry shouting for his

dinner, fingers crossed, his wife said 'you had it when

you came in. There's still food in your beard.' He put

his tongue round, tasted the food, and said 'yes, you're

right', and went back to sleep.

The second story is about a bald

headed butcher. His name was Mr. Yeardsley and a young

boy came to work for him. Mr. Yeardsley gave him the job

of sweeping the old sawdust off the floor and putting

more sawdust down. Twenty minutes later the boy was back

asking what he should do next. Mr. Yeardsley told him to

be very careful and clean the knives. Twenty minutes

later he was back for a new job. Yeardsley, after some

time, got fed-up with the boy asking what to do, so when

he came back after his sixth job, old Yeardsley told him

to take his trousers down and stick his behind in the

window. Twenty minutes later the boy was back saying

that he had done that. Yeardsley went mad and asked what

the customers had said, the boy replied "they said, good

morning, Mr. Yeardsley"! |

|

|

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

The 1930s |

|