|

|

|

A Tragic

Accident

During the First World War,

vast amounts of munitions were manufactured as part

of the war effort. When the war ended, there was a

large amount of unused ammunition to be disposed of,

some of which was recycled for scrap metal. From the

end of 1918 to 1920 there was a spell of prosperity,

followed by a deep recession, and much unemployment,

which lasted for a number of years.

Some firms cheaply purchased

ex-military ammunition for recycling, as a way to

earn money at this difficult time. Breaking-up live

ammunition to recover lead and copper, is, and was a

dangerous business. An appropriate explosives

license had to be obtained, high levels of staff

training were required, suitable workshop facilities

and protective clothing were essential, and health

and safety rules had to be followed.

It is listed in a Government

report that Major Philip Sydney Babty bought 45 to

47 million rounds of miniature live ammunition from

the Disposal Board and sold it to Premium Aluminium

Casting Company Limited of Birmingham. The company

always obeyed the health and safety rules, had

proper facilities, and paid between £3 and £4 a week

to the young girls who carried out the dangerous

work. In 1922, the company sold

160 tons of live 0.22 cartridges to the Dudley Port

Phosphor Bronze Company, who had a foundry in Groveland

Road, Dudley Port. The business was owned by Louisa Kate

Knowles and run by her husband John Walter Knowles, who

asked Harry Andrews, one of Premium Aluminium’s

Directors if he could get some ammunition for him, in

order to recover the lead and copper. He agreed to pay

£500 for the ammunition, plus half the profits from the

sale of the scrap metal. |

|

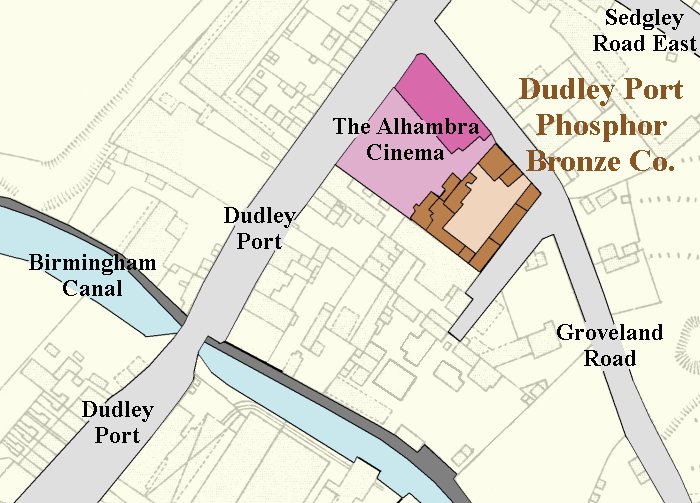

The location of the Dudley Port

Phosphor Bronze Company. |

|

It seems that another of Premium

Aluminium’s Directors, Mr. R. V. Dawkins carefully

advised Knowles, before delivery, about the health and

safety issues and informed him that he needed the

appropriate explosives licence. Knowles assured him that

he had one and ignored all of his advice. The workshop

in Groveland Road was totally unsuitable for the work in

hand. All that mattered was short-term profit.

Mr. and Mrs. Knowles ran a small

foundry on the Groveland Road site. They decided to use

an old pattern shop for recycling the cartridges, which

was 30 feet long by 27 feet wide, with a concrete floor,

and an old stove in the middle that had been used for

heating iron bars. There were no extractor fans or

proper ventilation. In order to maximise their profit,

they employed young girls between the ages of 13 and 16,

on very low wages, with no safety training, and no

protective clothing. They were paid between 2 shillings

and 4 pence and 3 shillings and 4 pence per week. 30

girls were involved in the project, but the actual

number at work on any day varied.

Ebor Chadwick, the foundry foreman,

was instructed to oversee the operation, even though he

had no experience with explosives and no safety

training. He realised that it was dangerous to use the

stove in the workshop because of the danger of an

explosion from the gunpowder dust that covered the

concrete floor and many flat areas, but his worries were

ignored by Knowles, who told him 'not to be silly'.

Chadwick usually left the girls to their own devices. He

hardly ever entered the workshop.

Monday the 6th March, 1922, began like any

other day in the workshop. It was a cold morning and so

a good fire was burning in the stove and the girls

happily worked, sitting on the ammunition boxes while

separating the lead and the copper in the 0.22 caliber

cartridges and tipping the gunpowder into open boxes,

that would be emptied into the canal at the end of the

day. At about a quarter to twelve, something terrible

happened. A spark, either from the stove, or possibly from one of

the girls’ hobnail boots on the concrete floor, caused a

massive explosion that blew the roof off the building.

The explosion sounded like a clap of thunder, as a thick

cloud of black smoke rose above the badly damaged

building and the pungent smell of gunpowder filled the

air.

After a short silence, the screams

and cries of the injured girls could be heard, as people

rushed to the factory to help. They came across a

terrible scene of death, injury and destruction. The

survivors were left with horrible burns and injuries. Some were naked

because their clothes had been blown away. They were

carefully covered with bags and sacks and conveyed to nearby Dudley Guest Hospital for treatment.

Within twelve hours of the explosion, twelve of the

girls were dead.

|

|

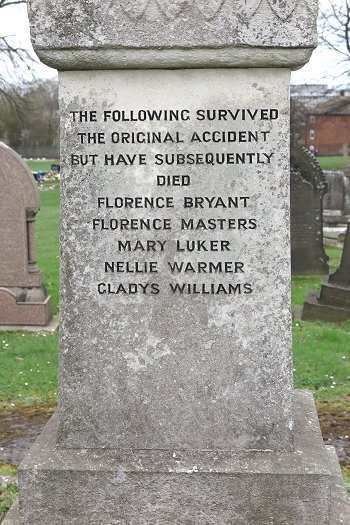

The memorial to the girls in

Tipton Cemetery. |

|

The hospital staff did all that

they could to save the others, but in spite of their

efforts another four died within hours, and three others

died in the following weeks. Four of the badly burned

girls survived against all the odds, thanks to the new

treatment of skin grafting, but their terrible injuries

would greatly affect the rest of their lives.

There was a huge public outcry over the way the girls

had been terribly exploited and treated by Mr. and Mrs.

Knowles. One man even walked to Dudley from Sheffield, to

offer some of his skin to save one of the girls.

Questions were asked in Parliament and Mr. and Mrs.

Knowles and Ebor Chadwick were charged with ‘feloniously

killing and slaying Mabel Weaver’. Mrs Knowles, as owner

of the factory, was also charged with storing explosives

without a licence.

The trial was soon held at Stafford

Assizes. Wealthy John Knowles, engaged the services of

one of the best lawyers, Sir Henry Curtis Bennett, and

they all pleaded not guilty. |

|

|

|

The

inscriptions on the four sides of the memorial. |

|

The Judge, when summing up, stated

that it was the worst case of manslaughter, he had ever

come across. He found it difficult to believe that

Knowles, a man with intelligence, could claim he knew

nothing whatever about the explosive act, after being

given advice, and some guidance from the Premium

Aluminium Casting Company Limited. Like many others he

said, Knowles had chosen, in the pursuit of avaricious

greed, to exploit, and put in extreme danger, very young

girls, desperate for work.

The court also found that it was

the duty of Mr. H. Andrews and Mr. R. V. Dawkins,

directors of Premium Aluminium Castings to see that the

ammunition was broken down under proper precautions, and

that their negligence was a contributing cause of the

explosion.

The jury decided that Louisa Kate

Knowles and Ebor Chadwick were not guilty, and so they

were acquitted. John Walter Knowles, aged 55, was

sentenced to five years Penal Servitude. Knowles lodged

an appeal against the sentence, but this was refused.

Many people at the time thought that his sentence was

far too short and that he had got off lightly.

Louisa Knowles, as the factory

owner, was ordered to pay compensation of £10,000 to the

families of the dead and injured. Only £5,650 of this

was recorded as being received. Both her and her husband

were wealthy and lived in a grand house. When John

Knowles died in 1951 he left over £50,000 in his will

and when his wife died in 1955 she left an estate valued

at £93,000. After the trial, Louisa Knowles

sold the Groveland Road factory, to Thomas Dudley.

The exact number of survivors of

the accident is uncertain. It is often stated that there

were four, but some records state that there were six.

Compensation was paid as follows: Mrs Bryant, who was

seriously, injured received £1,230. Three of the others,

who were seriously injured, each received £900. Another

girl, badly injured, received £200 and an injured child

received £105. The dependents of the 19 dead girls each

received £75. As already stated, the remainder of the

compensation was never paid.

| From a

contemporary newspaper cutting

from an unknown newspaper:

At Stafford Assizes, John Walter

Knowles, 55, manufacturer, was

found guilty of the manslaughter

of Mabel Weaver, one of the

victims of the Tipton workshop

on March 6. Mr. Justice Shearman

sentenced him to five years

penal servitude. Eber James

Richard Chadwick, 31, works

manager to Knowles, was found

not guilty and was discharged.

The girls

were engaged in breaking down

miniature rifle ammunition when

the explosion occurred. After

the verdict, Mr. Justice

Shearman was informed that

nineteen had died from their

injuries, and three were still

in hospital. The police proved a

previous conviction against

Knowles of eighteen months

imprisonment for receiving

stolen metal, and several

convictions for contraventions

of the Factory Act.

Mr. Graham

Milward, who defended Knowles,

said that ammunition worth

£2,800 had been seized by the

authorities, and there were

twenty three actions pending as

a result of the explosion.

In passing

sentence Mr. Justice Shearman

this was one of the worst cases

of manslaughter he had ever had

to deal with. He was not taking

into consideration any previous

offences at all. Knowles saw an

opportunity, as so many people

did now, to make a big profit on

a transaction. There was gross

exploitation of the labour of

little girls and boys – the

sweepers were the little boys –

in order to get more profit out

of it. If he were to treat the

case lightly he should be

wanting in his duty. |

|

A public appeal raised £4,766. Three of the girls,

all disfigured and disabled, were trained at college as

commercial clerks. They each received 12 shillings per

week, and a £6 dress allowance. The invested funds

provided the disabled girls, 5 in total, with a lifetime

income of 17 shillings a week, or a lump sum of £133 on reaching

the age of 21. The bereaved parents also

received funds from the Dudley Port Explosion Fund, which

raised over £10,000.

Councillor and hinge manufacturer, William Wooley

Doughty, J.P., Chairman of Tipton Urban District

Council, set up a relief fund on behalf of the town to pay for funerals etc.

|

The 19 girls who

sadly lost their lives, were as

follows:

| Elizabeth Aston |

age

14 |

|

Died

later, no address given. |

| Gladys

May Bryant |

age

14 |

|

15 West

Street, Dudley Port. |

| Margaret

(Maggie) Burns |

age

15 |

|

Sheepwash

Lane, West Bromwich. |

| Laura Dalloway |

age

15 |

|

36 Upper Church

Street, Tividale. |

| Edith Drew |

age

15 |

|

No1 House, 1

Court, Boat Row,

Tipton. |

| Annie

Eliza Florence Edwards |

age

15 |

|

77 "A" Block,

Munitions Huts,

Dudley. |

| Lucy Edwards |

age

14 |

|

Died some weeks

later. 3 Sheepwash Street, Tipton. |

| Elsie Follows |

age

15 |

|

196 Dudley Port. |

|

Violet May Franklin |

age

15 |

|

17 Cleton Street, Tipton. |

| Annie Freeth |

age

15 |

|

42 Farley

Street, Great

Bridge. |

|

Lily Griffiths |

age

15 |

|

Railway Street, Horseley Heath. |

|

Hannah Hubbard |

age

16 |

|

No.1 House, 5

Court, Dudley Port. |

|

Ethel May Jukes |

age

15 |

|

Died some time

later, no address

given. |

|

Nellie Kay |

age

15 |

|

Dudley Port,

Tipton. |

| Priscilla Longmore |

age

13 |

|

337 Dudley Port. |

|

Annie Naylor |

age

14 |

|

162 Dudley Port. |

|

Edith Richards |

age

14 |

|

Factory Road,

Tipton. |

|

Mabel Weaver |

age

14 |

|

3 Victoria

Terrace, Tipton. |

|

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Williams |

age

13 |

|

Cross Street,

Tipton. |

The five

survivors listed on the

memorial were:

Florence Bryant,

Florence Masters,

Mary Luker, Nellie

Warmer and Gladys

Williams

|

|

|

A final view of the memorial.

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|