|

|

|

Tipton Urban District Council

produced an annual report on health and hygiene in

the town, which was a good indication of social

conditions at the time. It covered everything from

housing, sanitation, disease and included data from

inspections of working premises, schools and

hospitals. In 1912 the report was produced for the

council by the town's Medical Officer of Health, Dr.

A. S. Underhill.

Housing

The standards of health and

hygiene were not very high. Working class

inhabitants tended to live there for convenience,

being close to their workplace. Upper classes also

lived there because of professional reasons rather

than by choice. Things were improving. In the

previous year, 97 houses had been reported as being

uninhabitable, 49 had been made habitable, 5 had

been demolished and 32 had been given closing orders

by the council. Houses were always available for

working men, at low rents and were generally being

better cared-for than previously. The town’s

mediocre standards of health and hygiene were blamed

on the working class inhabitants.

Domestic sanitation was

described as closet accommodation. Sanitary

conveniences were usually of the closet or cess pit

method with separate accommodation for ashes. Some

excreta was thrown onto neighbouring fields, other

onto tips hired by the council, or loaded onto

covered canal boats and transported to the country

to any farmer who required if for fertilizing his

land. Collection and transportation of human refuse

was carried out by men under the direction of Mr.

Clifton, sanitary inspector. At the time of the

report there were approximately 2,615 privies with

fixed receptacles, 10 with moveable receptacles.

There were 406 fresh water closet receptacles, 6

wash water closets. Mr. Clifton, the sanitary

inspector recommended that fresh water closets

should be connected to the sewers as soon as

possible. He bad noticed that many landlords were

reluctant to do this.

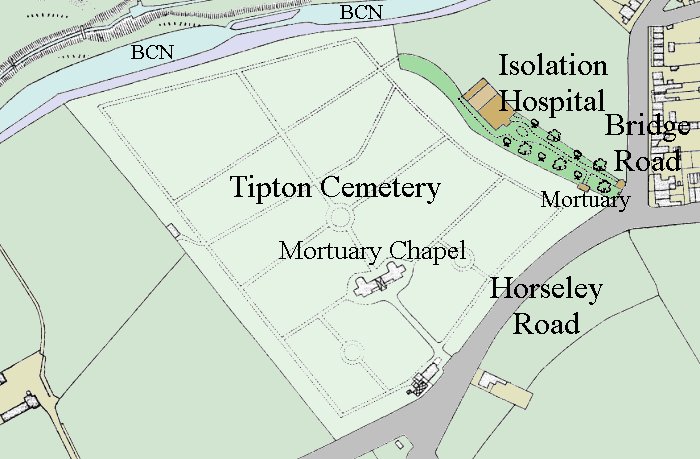

Isolation

Hospital

The isolation hospital stood

alongside the cemetery, at the junction of Horseley

Road and Bridge Road. In the report it is described

as not strictly modern, but had been renovated. It

could accommodate 28 patients, and specialised in

the treatment of scarlet fever, typhoid, and

diphtheria. There were two larger and two smaller

wards. Four beds were set aside for daily admissions

and there was a resident nurse, a caretaker and one

or two casual helpers. It was administered by Tipton

Council’s Cemetery and Hospital Committee. |

|

The location of the

Isolation Hospital. |

|

Disease

During 1912 there were 78

cases of scarlet fever, 11 cases of typhoid, 3

cases of puerperal fever, 13 cases of diphtheria

and membranous croup, 65 cases of pulmonary

tuberculosis, 23 cases of erysipelas, and 1 case

of polio. The cases of scarlet fever came from

the western part of Tipton and 11 of the cases

of diphtheria were in people between the ages of

5 and 25 years. Dr. Underhill regretted that

diphtheria antitoxin could not be freely

supplied to medical men in the area. He also

mentioned that the Tipton area was freer from

tuberculosis than many other districts because

of the towns high elevation, the healthy

occupation of men and the open condition of the

streets and alleyways.

In the previous year there

had been 45 deaths from diarrhoea and enteritis

in infants less than a year old. Dr. Underhill

suggested that this was due to the dusty nature

of the earth in the summer months. The dust

contained decomposed organic matter which was

inhaled by the infants. The death rate due to

diarrhoea and enteritis over the previous five

years was by the standards at the time,

incredibly high: 30 deaths in 1907, 47 deaths in

1908, 26 deaths in 1909, 30 deaths in 1910, 85

deaths in 1911, and 24 deaths in 1912.

In 1912 there were 11 cases

of typhoid, which resulted in 3 deaths. In the

previous five years, deaths from the disease

were as follows: 7 deaths in 1907, 7 deaths in

1908, 5 deaths in 1909, 7 deaths in 1910, and 2

deaths in 1911. There were also 56 cases of

scarlet fever.

In 1912 there was only one

outbreak of measles, confined to one school,

resulting in a single death. Because most

children were affected before they reached the

age of five years and in infants’ schools, they

could not be admitted to the isolation hospital.

If more than 50 percent of children were absent

with the disease in a school, it would be

automatically closed. Dr. Underhill remarked

that a large number of mothers completely

disregarded the need to nurse children sick with

measles. He had on numerous occasions seen small

children covered with the rash running around in

the streets, coming into contact with other

children. He charged working class mothers as

being mostly at fault here. Epidemics of measles

were frequent, as can be seen from the death

rate: 29 deaths in 1907, none in 1908, 21 deaths

in 1909, none in 1910, and 45 in 1911. There had

been previous outbreaks of the disease in 1900

and 1905.

For a period of 12 days,

from April 6th to April 18th, 1912 there were no

deaths and the hospital remained empty. |

|

Schools

Dr. Underhill had 16

schools under his control, 12 were council

schools and 4 were church schools. The school

furniture was regarded as old fashioned and the

ventilation was criticised. He recommended that

it could be improved by a regular and systematic

opening of windows.

Dr. Underhill visited the

pupils in each school twice a year in order to

examine them. He also attended a daily surgery

at his premises in Horseley Road at 10.30 in the

morning to which any child could be sent by his

teacher. During the examinations several

interesting facts came to light. In certain

parts of the town, the quality of the children’s

clothing was poor and in some cases bare feet

would have been better than the shoes that they

wore.

At that time the Tipton

Education Committee felt that it was not an

option to build a schools clinic because

Birmingham and Wolverhampton clinics were easily

accessible.

Schools were sprayed weekly

to combat disease, and district nurses regularly

visited them to examine the heads and general

cleanliness of the pupils. They also gave advice

to the mothers of children with verminous heads,

describing the best methods to keep them clean.

In 1912 the schools

attendance officer reported only one absentee

for blindness and 4 absentees for epilepsy. It

was believed that backwardness in children was

due to epilepsy, but Dr. Underhill stressed that

the cases he came across were, congenital. |

The Nurses' Home, in Lower

Church Lane, opened by Princess Aribert, the

King's niece, on 3rd August, 1909. Also known as

Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein.

From an old postcard. |

|

150 children were found to

be infested with vermin. In some cases the child

was sent away from school and not allowed to

return until clean. 1,033 boys and 1,047 girls

had their eyesight tested. 396 boys and 523

girls had perfect sight, but 101 children had

serious eye defects. 3 girls and 10 boys had

serious heart defects. The health of children's

throats was reasonable, but of the 940 boys and

934 girls examined, 113 of each sex had enlarged

tonsils. Dr. Underhill also advised the removal

of adenoids from 58 children.

Most of the children were

well fed. 1,026 cases were found to be fair and

52 were poor. Dr. Underhill was not satisfied

with the condition of the children's teeth. He

had not met a single child who used a toothbrush

and there was not a schools’ dentist.

Food

Most of the food consumed

by locals at the time was hygienic, but had a

low nutritional value. Mr. Clifton, the sanitary

inspector gained a certificate as a qualified

meat inspector, so the inspection of meat was

under his control. The cold meat on sale at

Great Bridge Market, late on Saturday evenings

was described as lacking nutrition, but on

analysis there was no sign of disease. Local

pigs were often inspected by special request and

in many cases found to have a disease. During

1912, 18 tubercular pigs had been condemned as

unfit for human consumption. The 24 local

slaughter houses were found to be generally

clean and serviceable, though most were old and

not up to date.

One of the favourite local

foods was fish and chips but fish frying was

regarded as one of the principle nuisances

because of the heavy fumes produced when frying,

which gave some people much cause for concern.

Dairies, cowsheds and

retail milk shops were visited during the year

by the inspector. All sources of milk supply

were kept under inspection. Dairies and milk

shops were generally found to comply with

standards, but cowsheds were criticised. Some

were ill ventilated and hygienically unfit for

dairy cows. In some cases where ventilating

units had been fitted, they were not used

because it was thought that fresh air diminished

the animals’ milk supply, which was dismissed as

fiction.

The town's water supply,

maintained by the South Staffordshire Water

Company, was praised as being good and

plentiful, the only criticism being its chemical

hardness.

The General

Area

Dr. Underhill’s report

gives a picture of an industrial town which does

not claim to have very high standards of health

and hygiene, but with good standards in many

workplaces, which were generally lofty, not

particularly overcrowded and occasionally

whitewashed.

The population in 1912 was

around 32,000 including a floating population

who moved to the town when work was plentiful

and left when work was not available. In 1912

there were 491 deaths, including 86 people sent

here from other districts. The birth rate was

slightly higher than the previous 10 years,

amounting to 1,143 registered births.

The traditional coal mining

industry was being superseded by a rise in the

number of foundries which created more jobs and

lighter work, such as polishing and assembling.

This was ideal employment for women and was

mainly taken up by younger single girls, who

formerly went into service.

Doctor A. S.

Underhill

Doctor Underhill, Tipton’s

Medical Officer of Health, had an outstanding

career. The Lancet, October 18th, 1890 includes

a report stating that Dr. A. S. Underhill, of

Tipton, was elected as president of the

Birmingham Society of Medical Officers of

Health. It was also reported in ‘Public Health’

January 1926 that Dr. A. S. Underhill was

congratulated for completing 52 years in the

public health service. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|