|

|

|

Ironworks

At the turn of the 19th century, Tipton and its

neighbouring Black Country towns were in an ideal

situation for the production of iron. The vast local

deposits of coal, iron ore and limestone, and cheap

efficient transport on the canal network meant that

the appearance of ironworks was almost inevitable,

especially because of the country’s growing appetite

for products made of iron.

Tipton’s iron industry began in

a relatively small way with the production of items

such as hinges, wood screws, awl blades, edge tools

and nail rods for the nail makers. At the time,

around one quarter of the local workforce were

involved in the production of nails. Whole families,

including several generations, from children to the

elderly, made nails.

Things began to change with the

development of steam engines, large machinery, iron

bridges, and the building of the railways.

|

|

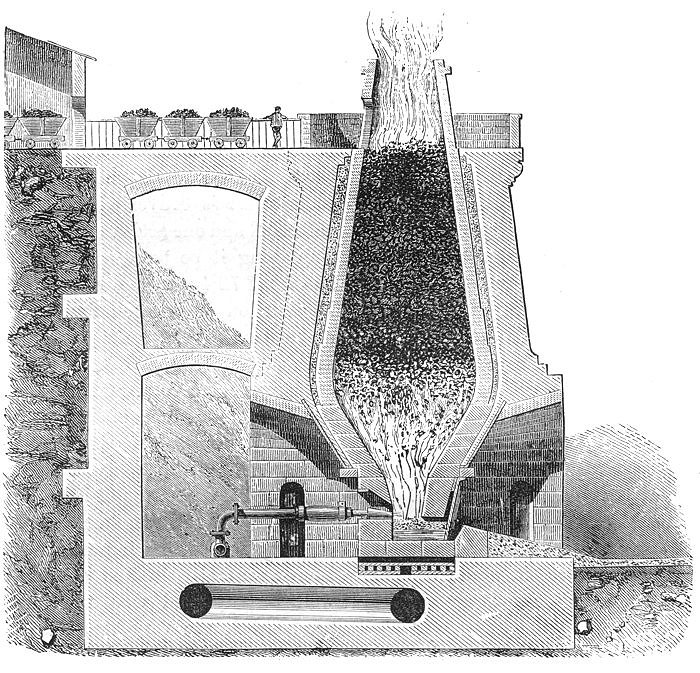

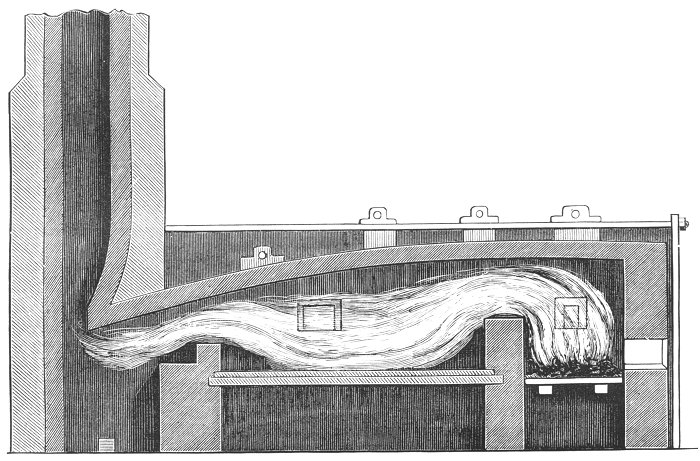

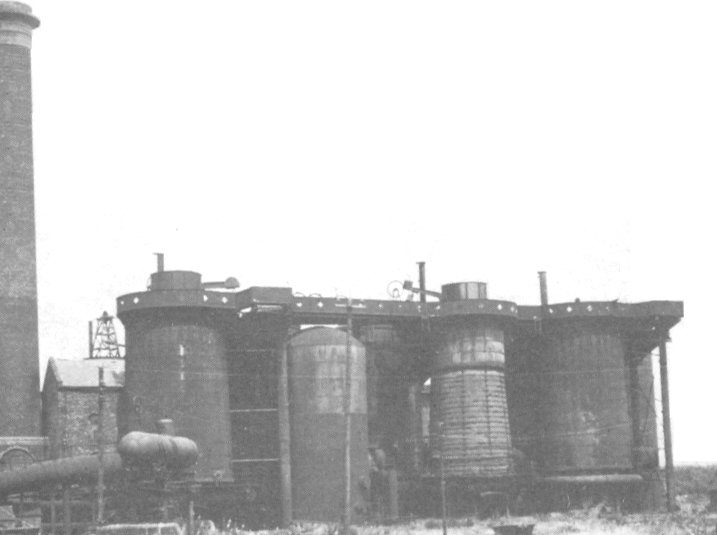

A 19th century blast furnace

which produced pig iron. |

|

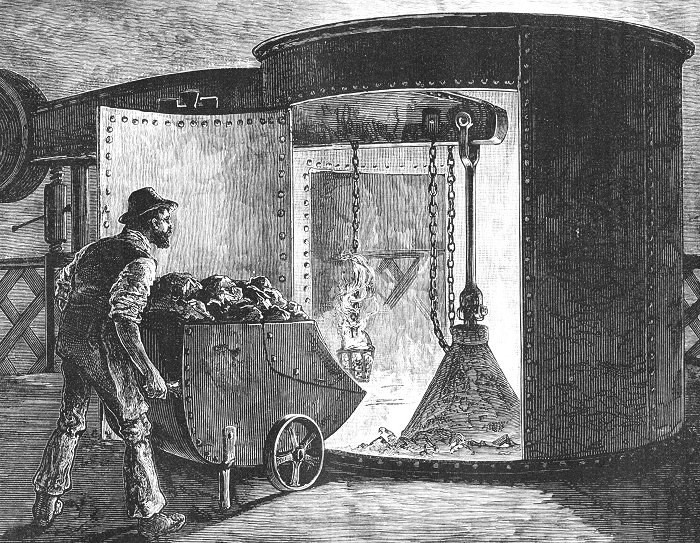

Charging a blast furnace. |

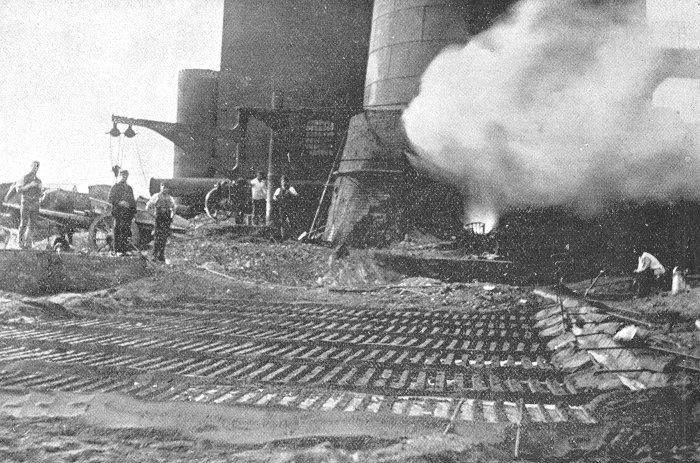

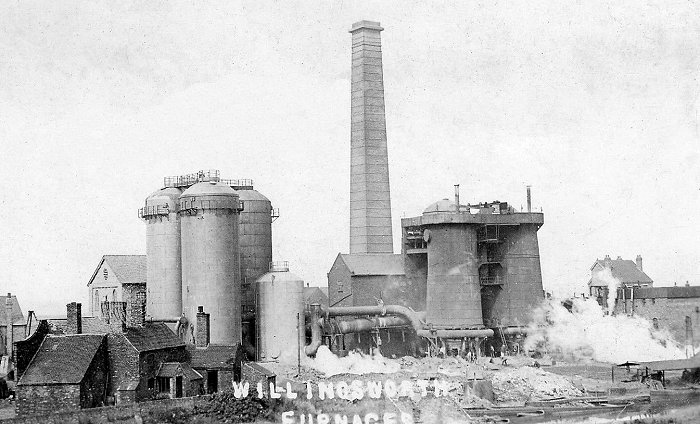

Tapping one of the

furnaces at Willingsworth Ironworks. The

molten iron was run into channels cut into

sand to produce iron ingots. This was known

as a pig bed. The iron was called pig iron

because during casting, the ingots were

likened to a piglet suckling milk from a

sow. |

| The most common method of producing wrought

iron from pig iron in the 19th century was

puddling, invented by Henry Cort in 1784.

Pig iron or scrap cast iron was melted in a

puddling furnace and stirred with a long pole,

which reduced the carbon content by bringing it

into contact with air, in which it burned. The

puddling furnace heated the iron by reflecting

the exhaust gases from the fire down onto it. In

the drawing below, the iron would be placed in

the central section. Because it was not in

contact with the fire, cheaper, poor quality

fuel could be used. After puddling, the iron was

hammered and rolled to remove the slag. |

|

A puddling furnace. |

|

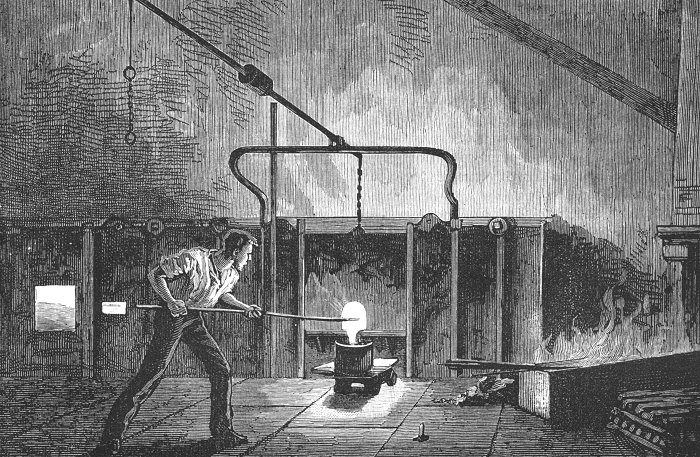

A puddler at work. |

|

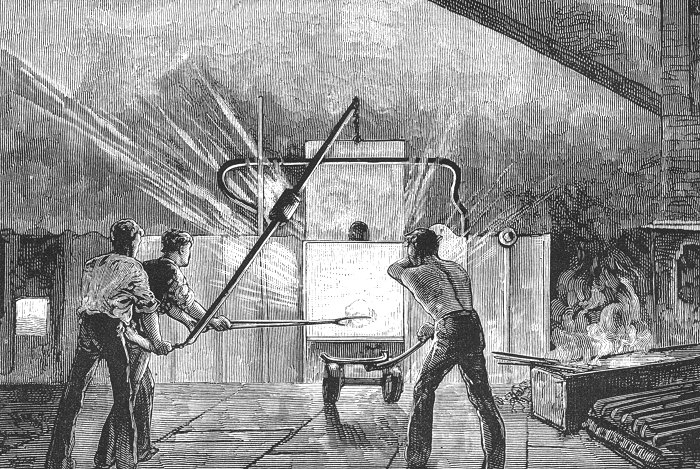

Puddlers at work. |

|

Some of Tipton's

Ironworks

Daniel Moore had a

water-powered slitting mill, with two undershot

water wheels and a steam engine. The firm produced a

wide range of nails and tacks, especially horse

nails, as well as shovels and tongs. Around 40

people worked there.

Edward and James Fisher and

James Bate employed around 100 people in the

manufacture of iron hinges. Zachary Parkes and

Company at Dudley Port had a single furnace that

produced between 20 to 25 tons of iron per week.

They also had a forge and a slitting mill.

George Parker & Company had

two furnaces that produced 20 or 25 tons of pig iron

per week at Coneygre Ironworks, Dudley Port,

established in 1794 by Zachariah Parkes. They had

three forge hammers and a rolling

and slitting mill. One of their products was boiler

plates. Another furnace was added and the business

was acquired by

the Earl of Dudley. The three furnaces then produced around 200 tons of iron per week.

George Parker & Company also owned Tipton Furnace,

also known as 'Parker's New Furnace'. It was later

called Coseley Moor Furnace.

Read, Banks, and Dumaresq had a

forge and a single furnace producing around 25 tons

of iron per week. Richard Hawkes and Company also

had a single furnace which produced around 20 tons

of iron per week. At Toll End was Taylor's Foundry

where heavy items such as parts for steam engines,

whimseys and machinery were cast.

The Great Bridge Iron & Steel Company Limited was

founded by James and Neal Solly, who traded as Solly

Brothers and were one of the oldest and largest

suppliers of puddled steel. There were two forges,

two merchant mills, and two sheet mills that could

produce up to 320 tons of iron and steel per week.

Another successful enterprise was the Crown Iron &

Galvanising Works at Toll End, run by Edward Bayley,

who also operated two blast furnaces at Eagle Works.

Crown Works were established in 1870 and were later

extended with the addition of two sheet mills and a

galvanising factory. There were ten puddling

furnaces and three mill furnaces, with a total

capacity of nearly 100 tons per week. The factory

employed around 200 men and produced best quality

black sheet iron and galvanised corrugated iron

sheet.

|

|

The two blast furnaces at

Willingsworth Ironworks that produced good forge

iron. From an old postcard. |

| Eagle Works, founded in about 1800 by Richard

Hawkes, once stood on a site that was later occupied

by Great Bridge Railway Station, alongside Eagle

Road. Around 1844 Eagle Works were put-up for sale

and the site was acquired by the South Staffordshire

Railway, in readiness for the building of the railway

station. The

factory had two blast furnaces, a double refinery

and a

large foundry capable of producing 100 tons of

castings per week. There was a boring mill, capable of boring

cylinders ten feet in diameter,

blast and boring mill engines, a

smiths shop, a fitting shop, a carpenters shop, plus

a manager’s house and three workmen’s cottages.

There were also collieries mining Heathen Coal, New

Mine Coal, and New Mine Ironstone, with two winding

and pumping engines, and three winding engines. Other large concerns included

the Portfield Works near Dudley Port, owned by James and

Charles Holcroft, which could produce almost every size,

shape, variety and section of iron, and had a large

galvanising department. Another sizeable ironworks

was the Church Lane Works run by George Gadd &

Company. There were 14 puddling furnaces, 2 mill

furnaces, and one ball furnace, with a total

capacity of 180 tons of bar iron and 200 tons of

puddled iron per week.

The Hope Iron, Steel and

Tinplate Company Limited at Summerhill had 4 mills. Plant and Fisher at Dudley Port Works produced

250 tons of iron per week from 20 puddling furnaces

and 3 mills. The Gospel Oak Iron & Galvanised Iron &

Wire Company had 24 puddling furnaces and 6 rolling

mills, and the Dudley Port Furnace Company, run by

James Roberts and Fred Deeley had a single blast

furnace with a capacity of 250 tons of pig iron per

week.

The Gospel Oak Iron Works, which

was founded by Samuel Walker and William Yates in

1817, began making cannon in 1822, but the business

failed. The sons of the owners took over and started

to produce ironwork for all kinds of building

projects, including Hammersmith Bridge, in London,

in 1825, and the cast iron columns for the Albert

Dock, Liverpool, in 1846. Similar columns were later

produced for the Gladstone Dock, also in Liverpool. In

1848 the business was taken over by John and Edward

Walker, who employed around 350 people, producing

large amounts of wrought-iron cannon

and tinplate. The business failed for a second time

in about 1860 and cannon manufacture was taken

over by three ex-employees who founded the Hope

Company. Around 1900 the Blackwall Galvanised Iron

Company acquired the Gospel Oak Company and exported

galvanised sheets to many parts of the world using

the product names Poplar, Blackwall and Gospel Oak.

Tubes were produced in Great Bridge by Wellington

Tube Works Limited at Wellington Tube Works. The

firm, founded by Joseph Aird started making tubes in

1861. Products included mild steel and wrought iron

tubes and fittings for gas, water and steam, along

with coated

and wrapped tubes, loose flanged tubes, grilled

metal tubes and special pipe work of all kinds.

Other locally made iron

products included cast iron grates and stoves

produced at the Moat Foundry, Summerhill by Charles

Lathe & Company, established in 1877. There were

also boiler makers, hurdle and iron fencing makers,

anvil makers and manufacturers of vices and hammers.

|

The blast

furnaces at William Roberts Limited

which closed in 1921. |

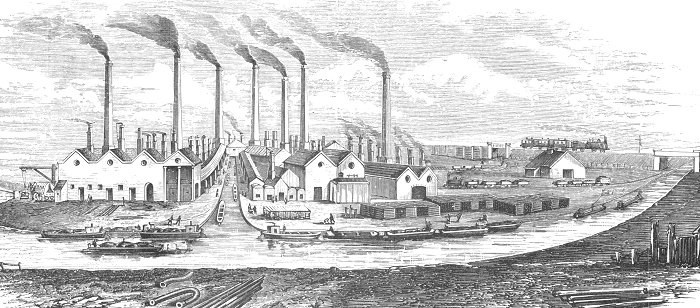

Bloomfield Ironworks

It all began when a local Tipton man invented

a process that revolutionised puddling,

throughout the country and much of the world.

His name was Joseph Hall, who was born in 1789.

In about 1811 he noticed how his employer,

carefully saved old scraps of iron for use at

the refinery, where large quantities of iron

were lost in the wasteful process of making it

into wrought iron by refining and puddling. He

began to follow his employer’s example and saved

all the odd bits and pieces of iron that were

lying about the works. Around 1816 he noticed

that the cinder from puddlers' boshes (the water

tanks where the puddler cooled his tools)

contained a quantity of iron, and so he began to

save this also.

Some time later, he tried adding some of the

bosh cinder to a puddling furnace and found,

rather to his alarm, that a violent boiling

occurred, the contents of the furnace running

out in all directions. He feared that the

furnace would be damaged, but the boiling ceased

and when he looked in the furnace he saw that

pieces of iron were present. When he gathered

them into a ball and hammered them together, he

was surprised to find that iron was the best he

had ever seen.

He had accidentally discovered an ideal

method of working a puddling furnace. The cinder

that he used consisted of small pieces of iron,

brought out of the furnace by the tools, mixed

with a rich iron oxide. When heated, the oxygen

had united violently with the impurities in the

iron, making the contents of the furnace boil,

leaving behind, high quality wrought iron.

He formed a partnership with Thomas Lewis and

in 1830 they bought a piece of land at

Bloomfield, where they built a small ironworks

with three puddling furnaces beside the canal.

The site was later connected to the main railway

line by sidings. Hall continued his experiments

to improve the process. There was a serious

problem with the cast-iron bottom plates of his

furnaces, which were attacked by the bosh

cinder. He overcame the problem by roasting the

cinder, which became known as bull-dog and was used for the furnace bottoms.

Bull-dog was

patented in 1838.

Bloomfield Ironworks in

1884.

He also discovered that a small addition of

some hammer cinder and mill scale (the iron

oxide that breaks off the surface of the iron as

it is rolled and hammered) fully protected the

furnace bottom plates. His process was now

perfect. Pig iron was charged into the furnace

in the usual way, the fettling or lining of

bull-dog and scale being repaired before

charging as required. The metal was then melted

down and in due course it began to work, as the

oxygen from the fettling united with the carbon

in the iron. The reaction was violent, and for

about half an hour the surface of the metal

boiled, with bubbles of carbon monoxide breaking

through, and burning with little blue flames or

puddlers' candles. Because of this violent

reaction, the process became known as pig

boiling or wet puddling.

Hall's patent greatly reduced the amount of

waste from puddling furnaces so that by 1900,

only 21 cwt of pig was needed to make a ton of

wrought iron. Since the furnace bottom was

formed of oxide, the supply of oxygen for the

elimination of carbon was assured. The amount of

silica was strictly limited to that in the sand

adhering to the pigs, plus the silicon in the

pigs themselves, so there was no build-up of an

acidic slag. The slag remained basic; as this

combines with phosphorus, the removal of that

unwanted element was facilitated. Furthermore,

the violent reaction of the oxides with the

carbon in the pig iron, by agitating the charge,

helped to ensure a thorough mixing and reduced

the time required to complete the process, which

also

reduced the amount of manual labour needed.

Thomas Lewis soon left the firm and Joseph

Hall was joined by two new partners, Richard

Bradley and Mr. Welch, who left in 1834 and was

replaced by William Barrows. The firm became

Bradley, Barrows and Hall. The factory was

greatly extended and the iron was sold under the

brand name B.B.H.

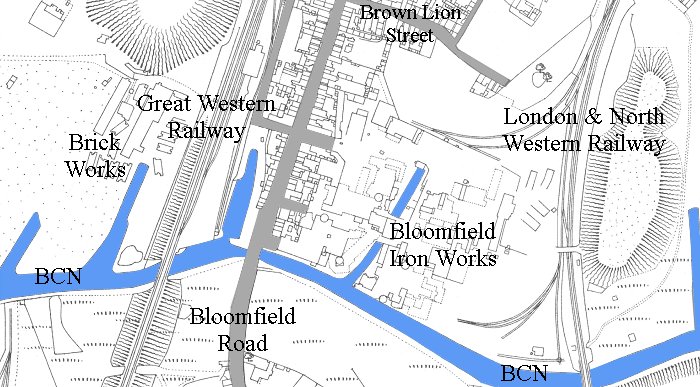

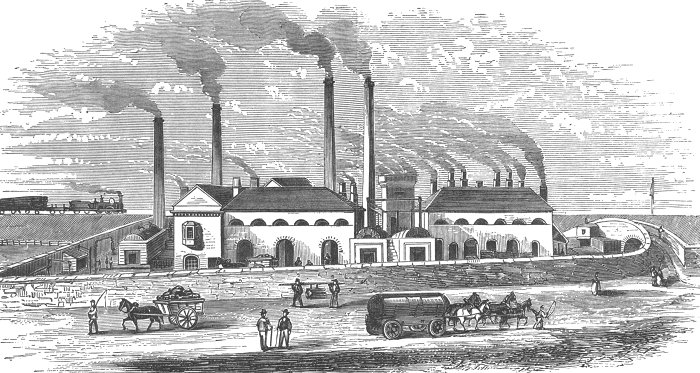

Bloomfield Ironworks in

1872.

Richard Bradley retired in 1844 and was

succeeded by Mr. Bramah, who lived at

Kingswinford. Mr. Bramah died in 1846 and the

firm became Barrows and Hall, William Barrows

and Joseph Hall being equal partners. In 1851

the firm employed 1,000 men.

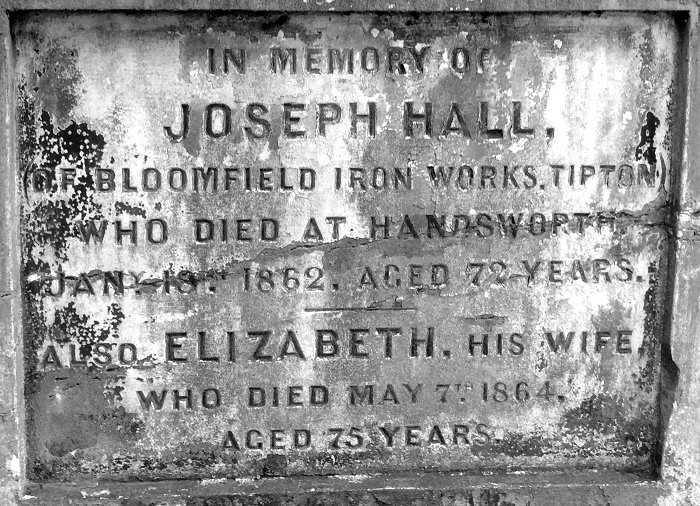

In 1849 Joseph Hall moved to Bloomfield

House, in Holyhead Road, Handsworth, where a

Farmfoods shop now stands. He died there on the

18th January, 1862 at the age of 72 and was

buried in a family vault at Key Hill Cemetery,

Birmingham.

Joseph Hall's family vault

at Key Hill Cemetery, Birmingham.

Joseph Hall's memorial stone, on the family

vault at Key Hill Cemetery, Birmingham.

|

|

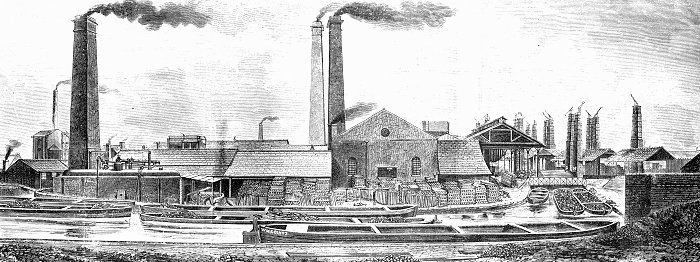

From Griffiths' Guide to

the Iron Trade of Great Britain. 1873. |

In 1848 two men were killed in a boiler

explosion at the ironworks. They were Mr.

Millington and William Perry. Several people

were injured. The boiler, weighing 7 to 8

tons was thrown about 70 yards across the

canal. After Joseph Hall's death the

company became W. Barrows & Sons. William

Barrows was born in Birmingham in 1800 or

1801. In the 1830s he lived in Hampstead

Row, Handsworth, before moving to

Springfield House, Dixon's Green, Dudley.

In 1861 he was living at Himley House,

Himley, (now a pub and restaurant) with his

wife Martha and four servants. Their sons

Thomas and Joseph were both ironmasters.

William Barrows died on 10th December,

1863 at Stafford Railway Station. In 1867

the firm had 58 puddling furnaces and eight

mills.

By 1872 there were 100 puddling furnaces

and 10mills and forges. There were around

800 employees producing approximately 800

tons of iron sheets, plates and bars per

week. Their iron was second to none. |

|

W. Barrows & Sons,

Bloomfield Ironworks.

By the late 1870s the industry was in

decline. Bloomfield Ironworks closed in 1902

and were offered for sale in local

newspapers. By that time trade was bad and

so no one offered to buy the site. Joseph

Barrows, the principal partner, died in

1903, and the works were again offered for

sale, but again no purchaser could be found.

In 1904, the site was sold privately for the

coal which was plentiful there. The factory

was demolished to clear the way for mining

operations at what became known as Bloomfield Colliery.

The final sale catalogue shows a large

site, covering just over 18 acres, but only

a small part of the site was occupied by

buildings, which had all been erected in a fairly

haphazard way. The various rolling mills lay

clustered together and were at all angles,

as were the puddling furnaces. The rolling

mills were under cover and roofs were

provided for departments that had valuable

machinery, such as lathes. Quite a

number of the puddling furnaces had no

protection from the weather at all. There

were bull-dog kilns, foundry and fitting

shops for maintenance purposes, and

extensive roll-turning equipment. Several of

the puddling furnaces still had their little

individual chimney stacks, and were not

connected to a boiler. There were several

boilers of the cylindrical egg-ended type,

which were coal-fired. It was in every way a

typical 19th century factory, which probably

couldn't have survived much longer without

being modernised.

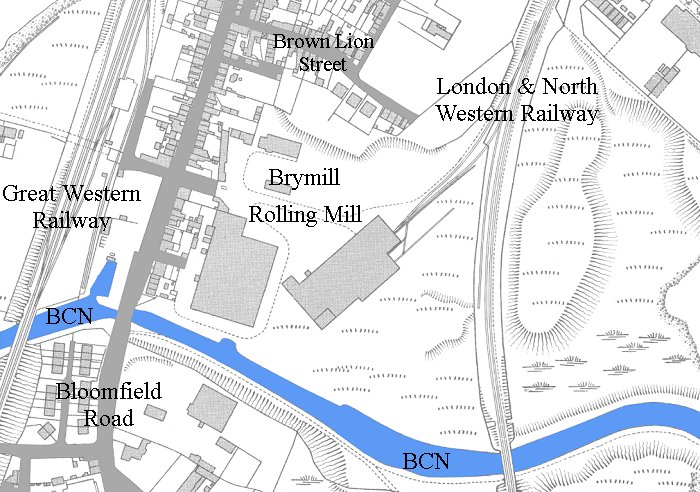

Bloomfield Colliery was purchased by

British Rolling Mills Limited and their

subsidiary, Brymill in the 1930s. Rolling

mills and a steelworks were built on the

site. Later Corus Steelworks constructed

their Firsteel Cold Mill and Service Centre

there. Most of the site is now occupied by

houses.

Brymill in 1938. |

| Wednesbury Oak Ironworks The business was founded in

1820 by Philip Williams and Sons, who were from an

old Shropshire family who moved to the area in 1776.

Philip started in business in about 1800. After

working for several companies, became a partner in

Gibbons, Whitehouse, and Williams, who built their

first furnace at Wednesbury in 1814. His partners

soon left the business and he purchased the

foundation timbers for a forge and mill from the

Government authorities at Woolwich, in 1818.

In 1820 the forges and mills

were built at Wednesbury Oak Ironworks and

manufacture of ‘Mitre Brand’ iron began. The factory

was extended and modernised in 1847 and 1880 for the

production of cold-blast pig iron. In 1829 Philip

Williams and his family founded and ran the Union

Furnaces at West Bromwich and also acquired the

Albion Works, and the Union Works at Smethwick,

along with Birchills Collieries and Furnaces, Mabbs Bank

Colliery, and

Bunker's Hill Colliery. By 1846 they were

employing over 5,000 men.

Philip Williams died in 1864

and the business continued to be run by members of

his family. One of his nephews, Walter Williams

became honorary secretary to a scheme that

encouraged ironworkers and colliers to keep their

children at school in the days before School Boards

were formed. He also anonymously wrote about the

value of education to the labouring classes and was

Chairman and President of the Mining Association of

Great Britain, Chairman of the local Mines Drainage

Commission, and Chairman of the Birmingham, Dudley,

and District Bank. He was also a Justice of the

Peace for Staffordshire and High Sheriff of

Staffordshire in 1880 to 1881. He lived at Sugnall

Hall, Eccleshall.

Around 1875 Wednesbury Oak

Ironworks were managed by George MacPherson who

became a partner in about 1890. The other partners

at the time were Philip A. Williams, Walter

Williams, and Joseph W. Williams. There were 3 blast

furnaces, 32 puddling furnaces, 5 mills and forges,

extensive collieries, saw mills, carpenters and

pattern makers' shops, foundries, millwrights,

engine fitters’ shops, blacksmiths’ shops, and

boiler makers' sheds. Finished products included bar

iron, angle iron, strips, nail rods, sheets, etc.

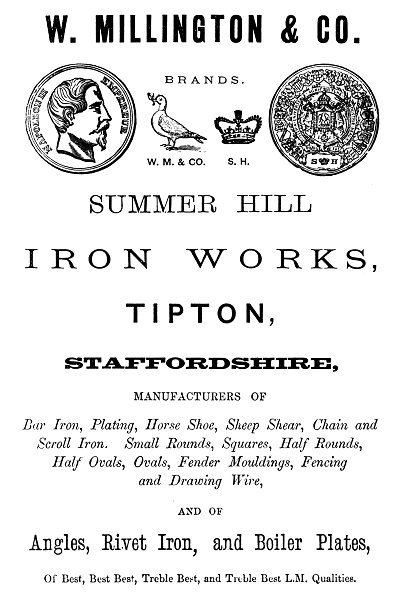

Summer Hill Iron Works

Summer Hill Iron Works was

founded by Thomas Millington in about 1820.

|

|

Summer Hill Iron Works. |

|

An advert from 1872. |

The firm was run by several generations of

the Middleton family, beginning as Thomas

Middleton, then Thomas Middleton & Son, followed

by T. Middleton & Sons, William and Isaiah

Millington, and finally W. Millington and

Company. By the 1870s it was run by Samuel

Millington.

There were 16 puddling

furnaces, 4 mills and forges, an annealing furnace,

a forge and up-to-date machinery.

Products included

boiler plates, merchant bar iron, plates, strips,

angle iron, shoe tip iron, horseshoe and rivet iron,

cable and chain iron of nearly every size, shape,

and variety.

The average production was around 200

tons per week and 150 men were employed at the

factory. |

|

Tipton Green Furnaces

The original two furnaces were

built in 1808 by Bradburn, Scott, and Foley, and in

the 1840s were let to Benjamin Gibbons, junior, of

Corbyn's Hall, who started to operate them in 1847.

He also rented the adjoining Tipton Green Colliery.

In 1848 he was joined by William Roberts who became

an equal partner in 1851. The furnaces originally

produced about 30 tons of iron per week using cold

blast, but they were enlarged and hot blast stoves

and winding engines were added to increase

production to 100 tons of iron per week.

In 1848 there were three furnaces,

which gave their name to a public house in Wood

Street. The old furnaces were demolished and

replaced by two new ones in the late 1850s and a

further two in 1860. In 1858 Benjamin Gibbons left

the firm, and in 1869 Alfred Roberts joined William

Roberts, and Mr. E. A. Spurgin joined in 1882.

Cowper stoves were added in 1889 and one of the

furnaces was rebuilt to include all of the latest

developments. The firm’s main customers were steel

works at Wednesbury, Bilston, and Round Oak. By the

1890s only two furnaces were in operation producing

200 tons per week of ‘Roberts' Tipton Green Iron’.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|