|

Wolverhampton in the 19th Century

At the time of the

Queen’s accession, Wolverhampton was a prosperous town, owing

its wealth not just to industry but also to the fact that it was

an important agricultural centre and market town, a mixed

economy town if ever there was one. Writing in 1839 one observer

commented:

“The town is on the

western borders of the mining district, and the neighbourhood

consequently abounds with mines of ironstone and limestone, with

furnaces, gorges and iron works. There is also a corn mill, two

worsted mills and chemical works for the manufacture of

sulphuric acid and nitric acids.

The trade of

Wolverhampton is greatly facilitated by its situation on the

direct line of the road to Holyhead, Manchester and Liverpool.

It also has the advantage of navigable communication to every

part of England by means of the Birmingham Canal”.1

The diversity of industry

in the town was one of its strengths and the list of trades

practiced must rival in sheer diversity any other town in the

country. The manufacture of japanned and tin ware was introduced

into the town from south Wales in the 18th century. Together

with Bilston, Wolverhampton was at the centre of this industry

and produced goods for home and foreign consumption. Although we

now tend to associate the manufacture of locks with Willenhall,

Wolverhampton too was an important centre for the industry but

one that tended to make more expensive products. The Chubb

Brothers, Charles and Jeremiah, first made locks in Portsea and

later moved to Horseley Fields in 1818. Later they moved to the

finest industrial premises in town, the Chubb Building.

|

Locally made products on display in part

of the interior of the Industrial Hall at the Wolverhampton Art

and Industrial Exhibition of 1902. The displays reflect the

confidence and prosperity of local manufacturers at the time. |

Tubing was

made for gas and locomotives and steel works of every

description from nutcrackers through files, rasps, vices, and

anvils to cycles and tricycles. Coach ironmongery was made, as

was kitchen furniture. There were also grease, chemical and

varnish works, malting and brewing, corn mills, and cooperages,

iron and brass foundries. There were no less than ten spectacle

manufacturers not to mention snuff grinders and watchmakers.

There were also many patent articles manufactured in

Wolverhampton including enamelled saucepans and other culinary

utensils “coated on the insides with a sort of porcelain

instead of tin”. |

|

The many fine Victorian

buildings in Wolverhampton are testimony to the prosperity of

the town in the 19th century. Its population in 1831, six years

before the accession of the Queen was 24,732. This can be

compared with the 6,647 of Walsall and the 37,000 of Stoke on

Trent. Between 1801 and 1901 the population of Wolverhampton

increased eight fold.

*

*

*

*

Despite the fact that

much of Wolverhampton is Victorian, the town still has something

of the townscape of a medieval market town. The market was south

of the church and the names Exchange Street and Cheapside gives

away its origins. Victorian Wolverhampton was slow to develop.

“Look at the town…Few

in England wear seemingly more antiquity in general aspect. Here

are houses built in Elizabeth’s day… Its name has a good old

Saxon sound; and its main street and market place have not yet

been reduced to the straight lines and cast-iron uniformity of

modern architecture”.2

It is interesting to note

that one of the old Elizabethan buildings mentioned by the

American writer Eliash Burritt* was the Old Hall on the site of

the present library. A firm of paper makers and japanners used

this until the early 19th century. The hall had been the moated

mansion of the Levesons, a family who had made their money

through the wool trade. In the 18th century Joseph Turton

junior, an iron factor, purchased the hall and removed the upper

storey and inserted sash windows. The hall later became Turton’s

hall. In the 1860s it was still used for industrial purposes by

F. Walston & Co. It is a pity that the hall has not survived, as

it would have be a rare and interesting example of a country

house converted to industrial use.

Like many industrial

towns, the rapid development left the local authority helpless

in the face of fast multiplying slums and the attendant problems

that they brought. As late as 1842 a Government report on the

slums of Wolverhampton read: -

“In

the small and dirtier streets, at intervals of every eight or

ten houses…the great majority are only three feet wide and six

feet high…These narrow passages are also the general

gutter…having made your way through the passage, you find

yourself in a space varying in size with the number of houses,

hutches, or hovels it contains. They are nearly all

proportionally overcrowded”.3

*Burritt is often credited with coining the appellation Black

Country, but the name pre dates Burritt by many years. The

people of Stratford Upon Avon have never forgiven Burritt for

linking them with Birmingham.

The

industrialization of the area and the concomitant loss of

greenery were noted by a German visitor in 1835.

“About Wolverhampton, trees, grass and every trace of verdure

disappear. As far as the eye can reach, all is black, with coal

mines and ironworks”.

Others were not so dismissive; the following writer (1851)

refers not only to the improvements taking place in the town,

but also to its quite magnificent settings:

“(The

town) is very salubrious…being seated on the summit of a bold

gravelly eminence…skirted by fertile pastures and gardens, and

having in the distance hills of great magnitude. Until about

twenty years ago, the town displayed but little beauty in its

streets and buildings”.4

There were some areas that

were particularly bad including Lower Stafford Street, Salop

Street, Horseley Fields and the Bilston Road area. Even as late

as 1865, £100 was granted to the Sewerage Committee to meet the

expense of covering over the public ditches. In a report on

Wolverhampton in “The Builder” of August 1872 the writer notes

“the most odious court system, countless courts of the most

unhealthy and objectionable character…with middens full,

stinking and confined, and deadly”.

The writer points out

what to us must seem surprising, that is the close proximity in

which the well-off lived to areas of utter squalor; he ends on

an ominous note:

“In Peel Street and its

neighbourhood and in what is called Caribee Island, the

condition of things is frightful: if the latter were really the

settlement of a tribe of wild Indians, it would be an object of

wonder to the civilized upper classes of Wolverhampton. These

are places which fight against the general salubrity of the

town, and out of which will one day come some frightful epidemic

to dispel the security at present indulged in, and rouse to

salutary action”.

The

poor housing was often not just a health hazard but a physical

danger as well. In 1876 a number of dilapidated houses in

Walsall Street collapsed killing a boy, one Edwin Brown.

|

| Like many

large towns, Wolverhampton took advantage of the Artisans’

Dwelling Act of 1875. This (Conservative) measure passed by the

Government of Disraeli, empowered local authorities to pull down

slums and rebuild decent accommodation for working class

families. In Wolverhampton there was a scheme to clear and

redevelop the area between Queen Square and Stafford Street.

This was the notorious Caribee Island area. The intention was to

provide suitable habitation for the displaced and land at

Springfield was purchased for that purpose. The Act was

implemented in 1881, when much of Lichfield Street was

re-aligned to provide a street of metropolitan grandeur. |

The new post office in Lichfield Street,

which opened on 29th March, 1897 is typical of the imposing and

attractive Victorian buildings that were appearing at the time. |

| The first

shop in Lichfield Street opened in 1883 and building was

completed with the Grand Theatre in 1894.

It was reported in 1818 that

the streets leading off Queen Square were substantial and well

built. The town was paved and well lit by gas. However prior to

this, one of the main problems for Wolverhampton had been the

maintenance of an adequate supply of water. Water was supplied

to Wolverhampton by wells sunk to a great depth under the rock

upon which the town was built (indeed, Banks’s Brewery still

uses one of these pure artesian sources). However this water

supply was inadequate for the needs of the expanding town and so

to supply this need a company was formed and an Act obtained in

1845 for the erection of a waterworks, which was opened in 1847.

The water was obtained from springs in the red sandstone rock at

Tettenhall and Goldthorn Hill where storage reservoirs able to

hold 2 million gallons were constructed. From these reservoirs,

water fell through 15-inch pipes, which were constantly charged,

so that in the event of fire, hoses could be attached to throw

water over the highest building. Water was also obtained from an

artesian well at Cosford. It was reported that the water in

Wolverhampton was remarkably pure and soft. These wells still

supply water to the town.

One of the ways in which

the health of the nation was improved was by the erection of

public baths and in this Wolverhampton was no exception. The

architect G.T. Robinson designed baths built in multi-coloured

bricks in bath Street. There were hot, cold, tepid and vapour

baths. The self-improvement that was such a feature of life at

all social levels was also in evidence here for attached to the

baths were reading rooms and rooms for chess and other

amusements.

|

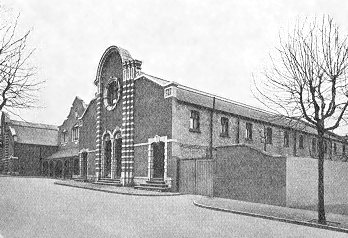

|

The Municipal Swimming Baths.

|

Despite the fact that

Wolverhampton was a major industrial town, we should not forget

that it was also a major market town. The numerous “Folds”

around the church are an indication of the importance of the

town as a medieval market. The nearby Halfpenny Green is a

reminder that here, cattle driven from Shropshire, were fattened

up at a halfpenny a head before being driven to town by way of

Salop Street.

|

|

As

was noted in 1876:

“Few,

if any, large manufacturing towns possess so large an element of

agricultural interests. The weekly market, which takes place on

Wednesdays, is largely attended by farmers of the county, and

also by those of the sister county of Shropshire and an enormous

quantity of cattle is disposed of and finds its way to the

shambles of the metropolis, as well as to those of the immediate

district”.5

(The word “shambles”, as used here, is the old name for a

livestock market).

In White’s Directory of 1861

the writer could say that Wolverhampton was “the most

populous borough and market town in Staffordshire”.

Many buildings serving

primarily agricultural purposes were witness to this unusual

combination of industry and agriculture. (The Royal Agricultural

Society held their 1871 show in Wolverhampton). An open market

was once held in Queen Square, formerly High Green. The modern

buildings of the Square still outline the ancient market area.

Before the erection of the cattle market, animals had been

driven into the town and sold openly on the streets, “often

to the annoyance of the public and injury to the beasts

themselves”.

The cattle market, designed by Edward Banks, was situated in the

Cleveland Road near to St George’s Church. It was thoroughly

well drained and had an abundant supply of water. Its capacity

for some 700 horses, 5,000 sheep and 3,000 pigs gives some

indication of its importance as a livestock market. The

delightfully named Fat Pig Market was situated in Bilston

Street, adjoining the Cattle market. This was opened in 1856 and

had accommodation for about 800 porkers.

The agricultural side of

the town’s activities is shown by the erection of an

Agricultural Hall in 1863, which occupied a prominent position

on Snowhill. A large moulding showing a plough and a sheaf of

corn surmounted the entrance. It was later used as a corn

exchange and for the display of agricultural implements. In its

open space of 1,200 sq yards, there were held flower, poultry

and dog shows. The recently demolished Gaumont Cinema occupied

the site of the Agricultural Hall. The cinema and the present

shop on the site both follow the contoured outline of the old

Agricultural Hall.

Few people in Wolverhampton

could fail to be aware both of the close proximity of the

countryside and the novelty of industry occupying former

agricultural land. One of the main complaints about St. Mark’s

Church in Chapel Ash, was that although the view from Queen

Square was impressive, it blocked out the vista of the Clee

Hills and Shropshire. It was also written of Horseley Fields, (a

ley for horses), that it is “but…now redundant in smoke, and

the noise of the forge and steam hammer is heard, where formerly

the lowing of cattle and the bleating of sheep were the

prevailing sounds”.6

Politically Wolverhampton came into its own after the passing of

the 1832 Reform Act. By this Act Wolverhampton was allowed to

send two M Ps to Westminster. The first two men who had the

honour of representing the town were Charles Villiers and Thomas

Thornley. Under the Redistribution of Seats Act of 1885, the

number of seats was increased to three. The constituency also

included Willenhall, Bilston and the parish of Sedgley. In 1848,

under the terms of the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835, the

town received a charter of incorporation. By this the town was

governed by a Mayor, twelve aldermen and thirty-six councilors.

The town was divided into eight wards, a further four being

added in 1896. From its incorporation, Wolverhampton council

acted with vigour and enthusiasm that was the hallmark, though

not the prerogative of the new industrial towns.

There was vigorous political

activity in the town with numerous political and social clubs.

In 1889 there were three Conservative Clubs, one being for

Conservative Working Men, and two Liberal clubs including the

Villiers Reform Club. As an expanding and prosperous town, with

a secure artisan class, there were quite a number of

institutions to help those of an industrious nature to rise in

the world, that social mobility so beloved of the Victorians.

Among the provident institutions of the town were a savings bank

and a number of friendly societies. The Wolverhampton Freehold

Land Society was established in 1848, for the purpose of

enabling working men and others to obtain plots of freehold

building land and thus become entitled to vote in parliamentary

elections. Initially 1,200 shares were issued to 750 individuals

with which land was purchased in Moorfields and Sedgley Road.

Also the society entered into an agreement for the purchase of

Whitmore Reans estate for £8,000.

All in all, the picture

of Victorian Wolverhampton is one of improvement, wealth,

energy, pride and redevelopment and this is reflected in the

many buildings of the town.

The term “Victorian” is one

of the most widely used descriptive words and also one of the

most imprecise. We speak of “Victorian values”, “Victorian

Architecture” and the progress of the “Victorians”.

Notes:

| 1. |

W.G. Hoskins, "The Making of the English

Landscape". |

| 2. |

Eliash Burritt, "Walks in the Black Country

and its Green Borderland", 1868. |

| 3. |

Factory Inspector's Report, 1842. |

| 4. |

White's Directory, 1851. |

| 5. |

Steen & Blackett, Wolverhampton Guide 1871. |

| 6. |

ibid. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

19th Century Britain |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Victorians

and Architecture |

|