|

Introduction

The term “Victorian” is one of

the most widely used descriptive words and also one of the most

imprecise. We speak of “Victorian values”, “Victorian Architecture”

and the progress of the “Victorians”. However, if we take Victorian

to mean anything appertaining to the reign of Queen Victoria, we are

speaking in terms of a period that lasted from 1837 to 1901: over

sixty years. When the young queen came to the throne, the horse was

still the main form of transport, although it was rapidly being

superseded by the railway locomotive, modern medicine was still in

its infancy and the French Revolution was still very much within

living memory. It has been noted that the British ruling class heard

the thud of the guillotine whenever they heard the cry “reform”.

When the queen died, the first tentative steps towards heavier than

air flight had been made, the motorcar was making its presence felt,

Roentgen had developed X-Ray photography and the aged queen was

captured on moving film. It is perhaps fitting that a monarch who

gave her name to a 19th century age of such vitality and forward

thinking should have died in the 20th century.

In 1901, despite the

magnificence of the Edwardian Age, when the world’s richest nation

was at last unashamed to show its wealth, the massive

self-confidence of the Victorians was beginning to crack. Doubts,

some moral, about the empire, competition from other nations such as

Germany and the United States and increasing industrial unrest, all

served to warn the far-sighted that all was not well. Therefore it

is inaccurate to speak of Victorian without some qualification, for

nothing in these years was static, as was to be expected over such a

long and rapidly developing period.

The purpose of this book is

to look at the Victorian heritage of Wolverhampton, its buildings,

artefacts and art; in the main those remaining, but also those that

only exist in memory and photograph or diagram.

|

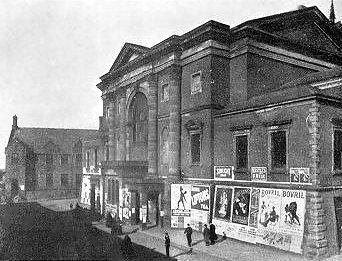

Wolverhampton Art Gallery, one of the City's

finest Victorian buildings, amidst the hustle and bustle of a busy

Saturday morning. |

Fortunately

the former are more than, or at least as numerous as, the latter.

These range from churches to factories, civic buildings to terraced

houses and places of entertainment, for Wolverhampton has a rich

Victorian legacy and a remarkably well-preserved one. We hope that

this book will be more than simply a record of buildings, for they

are nothing without the people who created them and used them. We

therefore hope to set the buildings within the social context in

which they were built. We also hope to show how changes in society

and religion were reflected in the ways in which buildings were

presented. |

|

When we began to write this

book, we originally intended to stay rigidly within the artificial

constraints of the modern Ring Road with occasional excursions

outside. We imposed this restriction on ourselves to prevent the

book becoming too unwieldy as ever more places were drawn in.

However during the course of our researches we realised that our

“excursions” outside were becoming increasingly frequent as we found

that the work of this or that architect could be compared with a

building outside our self-prescribed brief, or that a particular

building was of such interest that it could not be passed by. The

final result is that the main body of the work is therefore confined

to the centre of the town, but the looseness of this description

will soon become apparent to readers, especially in the sections on

villas and housing.

Although when we visit a

town that is new to us, we may admire buildings and may even have a

copy of Pevsner with which to identify certain features, we tend to

take for granted the buildings in our own town; buildings that we

use every day we may not notice. We have used Wolverhampton library

for more years than we care to remember and although we have always

considered it an attractive building, had never looked at it closely

until we came to write this book. It was only then that we began to

appreciate its wealth of detail in terracotta, fine shaped windows,

remarkably beautiful interior and warm attractive woodwork.

|

|

This book then is an attempt

to bring to more people’s attention the many fine Victorian

buildings of Wolverhampton, set in the historical and social setting

in which they were built. Buildings are far more than utilitarian;

they tell us a great deal about the social scene at the time. What

was their purpose? Is there a message in the building? What lies

behind their construction? In what way do they reflect the

development of the town? We hope that we have gone some way towards

shedding light on these questions.

At the end of the book

there are biographies of all the main architects, artists and

craftsmen who either worked in or designed buildings in the town,

together with a short glossary.

|

A long gone Victorian scene. On the left is

St. Peter's School and on the right is the old Exchange, which

dominated the western side of St. Peter's church. It was demolished

in 1898. |

| We have

deliberately avoided over-burdening the text with architectural

terms and although this may lay us open to the charge of

imprecision, we feel that for the majority of readers the esoteric

nature of much architectural vocabulary would make repeated visits

to the dictionary or the glossary tedious.

The writing of this book

gave us enormous pleasure and not a few surprises as we peeped

behind familiar facades to discover unfamiliar and often delightful

interiors. As we researched the buildings and statuary of our town,

it soon became clear that Wolverhampton in the 19th century

commissioned top architects and craftsmen, and that many of the

town’s own architects went on to gain a national reputation. The

civic pride so obvious in this process continues today. We hope that

this work will encourage others to visit and see anew

Wolverhampton’s 19th century architectural heritage.

We intended this book to be a

sober appraisal of an age and buildings that we admire, therefore we

have tried to confine our ire at modern philistinism and

aggrandisement to the footnotes.

Michael Albutt and Anne Amison, Codsall 1991

Since we wrote this book it

has remained dormant whilst other publications took precedence. At

one point we assumed that the manuscript was lost and the computer

information irretrievable. Recently however we found an extant copy

of the manuscript, much to our surprise and decided to revisit it.

The main body of the text remains the same except for a few

additions and re-writings to take note of refurbishments,

demolitions (thankfully few) that have taken place since the

original manuscript was finished. One paragraph that mentions a

particularly fine building, now demolished, we could not bear to

rewrite but a poignant picture from the Express and Star tells its

own story.

Of course, since this book

was completed, the town of Wolverhampton has become a city. We have

chosen to keep the designation town for the simple reason that it

was a town during the period covered by the book. However when we

refer to somewhere in its present context then city is used.

Many of the people

mentioned in the original acknowledgements have moved on from the

town in more senses than one but help given is help given and we

would still like to express our gratitude.

Michael Albutt and Anne Amison, Codsall 2004

|

|

|

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

the prologue |

|