|

The Renaissance of Stained Glass

|

“These Gothic windows, how they wear me out,

With cusp and foil, and nothing straight or square,

Crude colours, leaded borders roundabout,

And fitting in Peter here, and Matthew there!”

|

So wrote Thomas Hardy, who had helped “improve” a few

churches with Gothic additions when training as an architect

in the 1860s. The use of stained glass is one example of

Victorian design that has yet to receive the recognition

that it deserves. Until recently, Victorian stained glass

has been vastly underrated, not to say ignored: “insipid”,

“sentimental”, “the glass is Victorian and not worthy of

comment” are typical guide book remarks. Pevsner acerbically

commented that those who wish to study Victorian glass do so

out of “a somewhat morbid aesthetic curiosity”!1

Yet the mid to late 19th century saw what was undoubtedly

the greatest flowering of stained glass manufacture since

the middle ages, and by looking at the windows we often see

the best in 19th century artistic styles. They are “public

art”, if you will. Edward Burne-Jones, for example, saw his

stained glass designs in this light. They were a way of

giving art to those “whose childhoods had been without

beauty” (As his own had been).2

Nor had the windows’ teaching function, so important in

medieval times, been entirely lost for they reminded

church-goers of important tenets of their faith. So while we

can admire Victorian stained glass as art, we can also study

it to learn about how the Victorians saw their God.

In the 19th century techniques for working with and

colouring glass were rediscovered; tougher glass, less

likely to crack or shatter, became available and most

important of all, the demand for stained glass windows for

churches, public buildings and homes was ever increasing.

Whilst it is undoubtedly true to say that much of the

stained glass produced, especially towards the end of the

century, was of inferior quality, a great deal of 19th

century glass is worthy of our attention and further study.

Wolverhampton has excellent examples from several major

workshops; for a provincial town the glass in its churches

is of singular variety and quality. (See section on Artists

and Craftsmen).

|

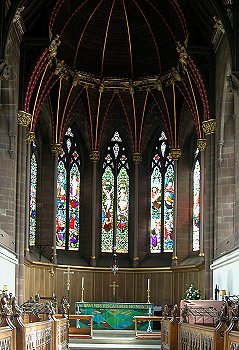

The fine stained glass windows at the

eastern end of the Chancel in St. Peter's Church, Wolverhampton. |

The reasons

for the 19th century Renaissance in stained glass manufacture

are manifold; some technical, some architectural, others

ecclesiastical. All are in some way connected with a longing for

an ideal past which began with the 18th century Romantic

Movement and which, as we have seen in the chapter on

architecture, later became something of an obsession for certain

Victorian artistic groups such as the Pre-Raphaelites and

architects such as A.W.N. Pugin.

Romantic beliefs about

an “ideal past” were reinforced for those wealthy enough to make

the Grand Tour through France to Italy and often on to Greece.

Such travellers saw not only classical remains but also the

glories of medieval stained glass in cathedrals such as

Chartres. This was a revelation as most English glass, certainly

that of the highest quality, was destroyed at the Dissolution of

the Monasteries and during the Commonwealth. The technique of

stained glass manufacture used in medieval times, especially

that of colouring had been lost. How the medieval glass makers

had achieved the glorious deep blue present in so much of their

work was a mystery. |

|

In the late 1840s a barrister and antiquarian named Charles

Winston, with the assistance of a chemist called Dr.

Medlock, rediscovered the technique for making blue glass.

Other pieces of medieval stained glass were analysed by

chemists at the glass firm of Powell of Whitefriars and

their secrets rediscovered. Chance Brothers of Swethwick

began to produce stronger, clearer glass. This so called

“antique glass” became essential for artists and designers.

As we have seen, architects from the 1840s onwards

increasingly turned towards medieval styles for their

inspiration. It was inevitable that a resurgence of interest

in, and use of the styles of this period should become known

as the Gothic Revival.

Established Church politics also left their mark. The Oxford

Movement of the 1840s founded by J. H. Newman, H.E. Manning

and others aimed at restoring the High Church ideals of the

17th century. Despite the reception of Newman and Manning

into the Roman Catholic Church in 1845 and 1851

respectively, the Oxford Movement’s ideals continued to gain

grounds throughout the 1850s leading to an increasing

interest in Anglican worship and ceremonial, which in turn

had a considerable impact on church design.

|

| All in all,

the stage was set for a demand for “medieval” stained glass. The

new churches, built as existing towns and cities expanded and

new towns grew; and the decaying churches of the established

parishes, lovingly if heavy-handedly restored by Victorian

worthies, all cried out for glass. A number of workshops

fulfilled this demand. |

Part of the north window in the Memorial

Chapel in St. Peter's Church, Wolverhampton. |

| The

greatest was undoubtedly the firm of Morris and Company, much of

whose glass was designed by Edward Burne-Jones. Unfortunately,

Wolverhampton has no ecclesiastical glass from the Victorian

heyday of Morris and Company, although Wightwick Manor has fine

domestic examples and those prepared to travel to Birmingham and

Shropshire will be rewarded by some fine examples. The town does

however contain good examples from other prominent workshops.

Styles in stained glass did not remain constant through the

Victorian period. In the 1850s and 60s “medieval” glass was

popular. It fitted well with the prevailing Gothic style of

the new and restored churches, and many churches installed

windows showing lots of small scenes in predominantly dark

tones which must have made their interiors dim and gloomy.

However, as in else, fashions in glass changed as the

century progressed. By the 1870s and 1880s more naturalistic

designs, with larger scenes and fewer dark colours, were the

order of the day thanks to the influence of the

Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements. Churches found

themselves without outmoded and unloved windows. So in the

1870s, 80s and 90s many Gothic designs were replaced, having

stayed the course for a remarkably short time. St. Peter's

Church is a good example of this trend. In the 1850s, after

the church was restored, Gothic windows by the top firms of

the day, Hardman and Company and Michael O’Connor, were

installed. By the 1870s these were already being removed and

gradually replaced by the designs that we see today; by the

end of the Great War they were all gone.

Notes:

| 1. |

Pevsner, "The Buildings of England:

Cambridgeshire", p.363. |

| 2. |

Penelope Fitzgerald, Edward Burne Jones,

Hamish Hamilton. 1975, p.85. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Architecture and the Victorians |

|

Return to

the

Contents |

|

Proceed to

Civic and

Public Buildings |

|