|

Early history

In 985, King Ethelred gave several

large pieces of land to Lady Wulfrun, an Anglo-Saxon

noblewoman and landowner. He granted the land to her in

a charter. Nine years later she gave several pieces of

land to the Monastery of St. Mary in Wolverhampton (now

St. Peter’s Church), including land at Bilston,

Brownhills, Willenhall, and Pelsall, then called

Peolshale. The land became part of the Deanery manor

under the control of the Canons of Wolverhampton, until

after the Norman Conquest when it became Crown property.

The Domesday Book described

Peolshale as half a hide of 'waste', belonging to the

Canons of Wolverhampton. The term ‘waste’ meant that no

taxes were collected from it, possibly because it was

uninhabited. Half a hide of land was about 60 acres. At

that time the area was covered by dense woodland and was

part of Cannock Forest. King William gave Peolshale to

fellow Norman, Robert de Corbeuil, for his assistance in

the conquest. Robert de Corbeuil’s descendants soon

included the territorial title 'de Pelshall' in

their name, which eventually was shortened to 'Pelshall'. The name

survived until the granddaughter of the last Sir Thomas

Pelshall, married the Earl of Breadalbane, in the 18th

century.

Little is known of Pelsall’s early

history. Ernest James Homeshaw, in his book ‘The Story

of Bloxwich’ published in 1955, includes a reference to

a document in the British Library, dated 1215 to 1224

that refers to a mill at Peleshale. This could have been

beside the Clockmill Brook that flows to Goscote, which

is considered to be the site of the earliest settlement

in the area. In 1286 Robert the miller had two acres of

land, possibly by the mill.

The Staffordshire Assize Roll of

1272 includes a reference to John de Chelesle, who

chased and caught William, son of Robert de Thene, and

Adam, son of Alote, on the heath at Norton. He accused

them of breaking into his Lord's grange at Pyshalle,

then bound and beheaded them. He was arrested for

the brutal act and taken to the Bishop's prison at Eccleshale, from where he quickly escaped. He was soon

recaptured and later beheaded.

At this time the area was still

part of Cannock Forest, the chief forester being Phillip

de Montgomery who in 1294 had two acres of rent-free

land. In 1300 the forest at Pelsall ceased to be part of

Cannock Forest and so was freed from the strict forest

laws. This allowed the area to develop. In 1311 the

first church was built in the village and in 1327 eleven

of the villagers paid the sum of £2.12s.0d to be listed

on the Subsidy Roll, a tax that was granted by the first

parliament of King Edward III to meet the expenses of

the Scotch War.

|

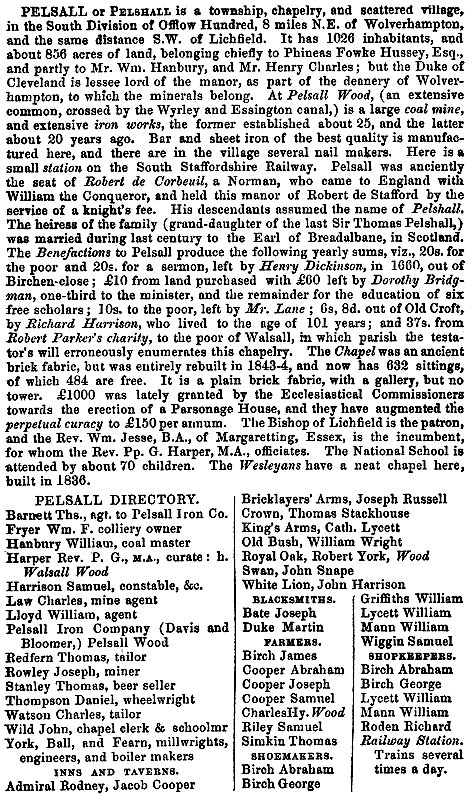

From William White's 'History,

Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire' published

in 1851. |

Sadly, little survives from those

early years. Remains of an ancient moated farm were

found near to the old fingerpost, at the junction of

Norton Road and Lichfield Road. The farm measured 168

feet by 80 feet. Remains of another moated building

could be found in a grove in the Parkfields, opposite

Pelsall Hall, but were destroyed in the 19th century by

coal mining.

In medieval times the village was

centred on Mouse Hill, with a population of 14

households in 1563. The first recorded ale house in the

village was opened by William Horton, who obtained his

brewing license in 1593. The population continued to

grow. In 1665 the Hearth Tax returns list 51 households,

14 of which were not eligible to pay the tax. The

pre-industrial community, living on the higher ground

around Mouse Hill had a church, a manor house, a smithy,

a communal oven, an animal pound, water from several

wells, farmsteads, and a village green.

In the 17th and 18th centuries,

road transport was difficult because many roads were

simply dirt tracks that were almost impassable during

wet weather, especially for heavy loads. Pelsall’s

economy was greatly boosted by the coming of the canal,

which led to a lot of industrial development in the

area. The Wyrley & Essington Canal opened in 1797 to

overcome the problems of transporting coal from the

mines in the Cannock area to Wolverhampton and the

Birmingham Canal.

|

|

An Act of Parliament was passed on

30th April, 1792 to allow the work to commence. Much of

the finance came from Wolverhampton businessmen,

principally the Molineux family. Work soon started under

the canal company's engineer, William Pitt. There were

two branches, one to a colliery at Essington and the

other to Birchills near the centre of Walsall. The canal

joined the Birmingham Canal at Horseley Fields,

Wolverhampton, and opened on 8th May, 1797. The work

included the building of Chasewater reservoir, that was

built as a canal feeder reservoir. The canal followed

the contours of the land, to avoid the building of

locks. Some of the canal boats were wider then usual,

because they didn't have to pass through narrow locks.

They were unique to this canal and were known as

'Amptons' after their destination, Wolverhampton. Being

a contoured canal and following an extremely circuitous

route, it became known as "The Curly Wyrley".

Gilpin Arm was built in about 1800

by William Gilpin, an edge tool maker at Wedges Mills

near Cannock, to transport coal, iron and limestone to

his mill. William Gilpin and his son, George, traded as

William Gilpin and Son, Wedges Mills, Cannock. They had

several pits that were connected to the arm by tramways.

By the 1840s the arm was no longer in use. When the area

was redeveloped in the 1970s, in the form of the Ryders

Hayes Estate, Gilpin Crescent was named after it.

The Hussey family of Little Wyrley

were farmers and landowners who acquired a lot of land

in the Pelsall area. In about 1790 their land was

purchased by Abraham Charles, from Kings Bromley. He

also purchased Pelsall Hall, where his descendants lived

until 1917, by which time they owned about one third of

Pelsall Parish. The Charles family had acquired the

mineral rights in some areas and greatly benefited from

the growth of the coal mines. They extended the hall and

purchased other properties including a house called

Peolsford, which was used to house families of Belgian

refugees during the First World War. In 1917 the family

sold their property in the area including the hall,

which was purchased by the Health Authority and

converted into a tuberculosis sanatorium.

In 1836 a national system of Poor

Law Unions was established under the terms of the Poor

Law Amendment Act of 1834. The Unions were groups of

parishes that provided for the poor in their area.

Pelsall became part of Walsall Poor Law Union.

Industrial Growth

Thanks to the canal, it was now

much easier to transport heavy items in and out of the

village. This led to the growth of local industries and

an increase in the population, as people moved into the

area to find employment. In 1801 the population was 477,

which increased to 1026 in 1841. By the 1840s nearly

thirteen percent of the local population were nail

makers, many of whom lived in Allen’s Lane and Heath

End. There was also Thomas Otway, who was listed as a

nail factor with a large house and a mill, presumably

a slitting mill.

Many coal mines opened in Pelsall,

both shallow mines, where the seams lay a few yards

below the surface, and deep mines. The coal lay between

layers of shale and sandstone. The larger mines included Pelsall Hall Colliery, which had a tramway leading to a

canal basin and wharf, and Goscote Old Colliery, which

was beside a canal wharf. There was also Blue Fly Pit,

which was known locally as ‘The Lemmie’. Accidents were

common and many people lost their lives. In 1859 the

winding machinery at Pelsall Wood Colliery went out of

gear, resulting in one fatality, and in 1871 three

people lost their lives when part of Highbridge

Colliery, owned by Elias Crapper, flooded. In 1870 there

had been an explosion in the colliery that resulted in

two men and a boy being buried alive. They were rescued,

but one of the men was badly injured.

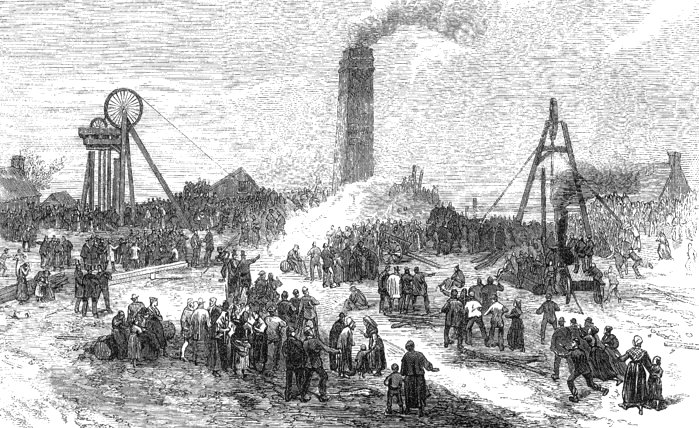

The most serious mining accident

took place at Pelsall Hall Colliery on 14th November,

1872 when water broke into the old workings. The cage

could only be brought to the surface once, leaving many

trapped miners underground. A vast amount of water had

to be pumped out before the men could be reached. Two

pumps were quickly set up, along with a large bucket

that could raise 25 cwt of water at a time. Around

60,000 gallons of water were removed hourly for seven

days, amounting to about 6½ million gallons.

|

|

The accident at Pelsall

Colliery. From The Illustrated London News. |

|

It was thought that the trapped men

were in the shallow workings and that trapped air could

keep them alive. Large numbers of relatives and friends

waited at the pit head for news, and on the third day,

Sister Dora arrived from Walsall Cottage Hospital. She lived

with the waiting relatives, and distributed blankets and

food at the pit head. She did everything possible to

support and comfort them at that terrible time. Twenty

one bodies were eventually recovered, and were buried

together in Pelsall Churchyard, where there is a

memorial obelisk of Aberdeen granite. Unfortunately one

of the bodies, that of John Hubbard, was never

recovered, but the local community got together to raise

money to help the victim’s families, which included the

selling of specially printed memorial cards. A total of

£84 was raised. Hillside Crescent and Hill Wood, which

were built in the mid 1960s, now occupy much of the

colliery site.

There were two foundries in the

area, Yorkes Foundry on Lichfield Road which closed in

the early twentieth century, and Ernest Wilkes’ brass

and iron foundry in Mouse Hill, close to the canal,

which closed in 1978. The business was founded by Joseph

Wilkes in 1852. His son Ernest took over when he

retired. Joseph and his wife had six children before

moving to ‘The Sycamores’ in Church Road. Ernest

purchased a number of properties in 1917 when the

Charles family sold the Pelsall Hall Estate.

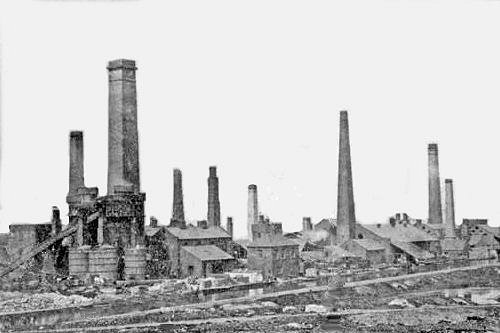

Pelsall’s best known heavy

industrial site was Pelsall Ironworks, which stood on

Wood Common, alongside the canal. The factory opened in

about 1832 and was owned by Wolverhampton banker,

Richard Fryer, along with several adjacent coalmines.

The ironworks gained a reputation for producing the best

quality bar and sheet iron.

Richard Fryer died in 1846, and

Boaz Bloomer, J.P. a prominent industrialist from Holly

Hall in Dudley, joined forces with Mr. Davis to form

Davis and Bloomer. They purchased the ironworks and

expanded the factory and the collieries. Boaz Bloomer’s

family had been in the iron trade for several

generations. He was born in 1801 and married Catherine

Hornblower, on 15th December 1825 at St. Thomas’s Church

in Dudley. They had eight children: Caleb, Boaz Jr.,

Esther, George, Giles, Prudence, Sarah and Benjamin.

Catherine died in 1849. Three years later, Boaz married

Emily Treffrey.

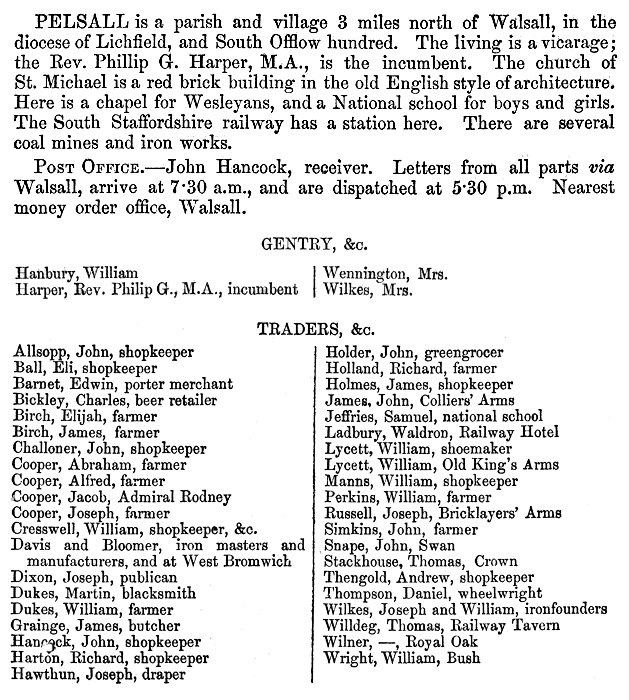

|

From Harrison, Harrod & Company's 1861

Directory and Gazetteer of Staffordshire.

|

In 1865 Boaz Bloomer purchased

Davis’s share of the company and began to run it with

his son, Boaz Jr. It became the Pelsall Coal and Iron

Company. By the 1870s, several hundred men worked there,

which caused a rapid rise in the local population. Many

of them moved to the Heath End and Pelsall Wood areas

with their families. A lot of the new employees had come

from the Ironbridge area. Coal was transported to the

factory by a network of tramways, and also from a canal

basin, next to Pelsall Ironworks. By 1872 there were

forty puddling furnaces, two blast furnaces, seven mills

and forges, a gas house with a gasometer, and limekilns.

The Pelsall Coal and Iron Company’s products were sold

throughout much of the world including Canada, China,

India, Norway, Sweden, and the United States.

Ironwork was hard physical labour,

and liquid refreshment was essential. Beer in buckets

was brought to the factory from the Free Trade Inn in

Wood Lane. The men were partly paid in tokens that had

to be exchanged for goods in the company’s ‘tommy shop’

in Wood Lane, near the canal bridge, where employees

could exchange tokens for goods at a lower cost than in

a regular shop.

Boaz Bloomer was a staunch Wesleyan

Methodist and a generous benefactor to the village. He

supplied the land for the building of the Wesleyan

Methodist Church in 1858, which stood in Chapel Street,

and largely funded its construction. When the church

opened on 14th July, 1859, he was made treasurer. His

son Ben Bloomer was church organist.

|

|

Boaz also contributed £750 towards

the building of the minister’s house and gave £1,000

towards the building of the Wesleyan day school in

Chapel Street in 1866, where he became Sunday School

Superintendent.

In the 1880s Chapel Street was developed

by the Bloomer family, who built houses for company

employees, near to the chapel and school.

|

Pelsall Ironworks. |

|

The ironworks and the collieries

acquired a rail link to the London and North Western

Railway in 1865, and an interchange basin was built to

transfer coal from barges to the railway.

In the 1860s Boaz Bloomer opened a

reading room at the iron works in which newspapers and

periodicals were available for the employees to read. He

believed in the importance of education, and in the late

1860s introduced a scheme to help company employees pay

their children’s school fees. He soon made it a

condition of employment, that all employees’ children

had to go to school. In 1870, Boaz Bloomer and his

family had a large house built at 46 Church Road, called

‘The Sycamores’, which was later occupied by Ernest

Wilkes, a brass and iron founder.

Boaz built another large house in

the 1870s called ‘Riddings House’ which stood on the

corner of Wolverhampton Road and Wood Lane. In 1900 it

was owned by local mine owner John Starkey, and then

acquired in the 1920s by George Harrington, a local

baker. There were tennis courts in part of the grounds

that became the headquarters of the first Pelsall Lawn

Tennis Club. After lying empty for some time, the house

was demolished in the 1950s. The coachman’s house still

stands in Wood Lane. Boaz died in 1874 in Kensington,

Middlesex. After his death, his sons continued to run the business.

Boaz Bloomer Jr. lived in Grove

House, which was later occupied by Joseph Bullock,

Managing Director of the Pelsall Coal and Iron Company.

Groveside Way now stands on the site of the house.

The Pelsall Coal and Iron Company

remained profitable until the recession in the iron

trade in the 1880s. The factory began to open only one

week in every three, and by March 1891 it was

£3,647.11s.7d. in debt. In 1892 the bank demanded the

repayment of a £20,000 overdraft, which pushed the

company into liquidation. The collieries were sold to

the Walsall Wood Colliery Company, and Bilston

Steelworks bought much of the plant in the factory. The

buildings and chimneys on the site were demolished in

the 1920s when many locals came to watch the spectacle.

The site is now part of Pelsall North Common.

|

|

Chapel Street in the

1930s. From an old postcard. |

|

The Growing Village

The village became less isolated

with the coming of the railway in 1849, which changed

many people’s lives. The building of the South

Staffordshire Railway was authorised by an Act of

Parliament on 3rd August 1846 that allowed the

construction of a railway line from Dudley to Lichfield

via Walsall. It was designed by civil engineer,

John Robinson McClean, who

obtained a lease for the line on 5th August,

1850. He agreed to operate the line for 21 years from

1st August 1850.

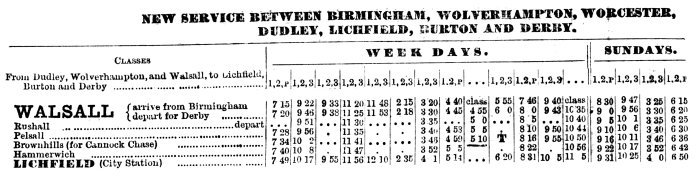

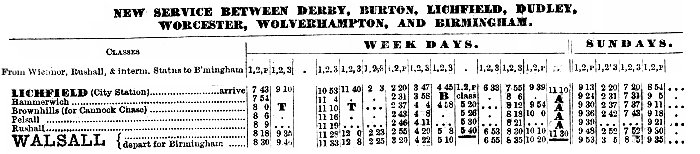

The first

section between Bescot Junction and Walsall opened on

1st November, 1847, followed by the opening of the

section to Wichnor Junction, on the Midland Railway, on

9th April, 1849. The line started at Dudley and ran

through Wednesbury, Walsall, Rushall, Pelsall,

Brownhills, Hammerwich, Lichfield, and Alrewas, to

Wichnor Junction. The final section from Walsall to

Dudley Park opened 8th May 1850 and was extended to the

new railway station at Dudley in 1860. Pelsall Railway

Station was roughly half way along Station Road, near to

where the public footpath is today.

|

|

| |

|

|

From the

London & North Western Railway's

timetable, August 1874. |

|

|

In

1861 the lease for the South Staffordshire

Railway was transferred

to the London and North Western Railway Company,

who then operated the line. The company took it over on 15th

July, 1867 and it became part of the London and North

Western Railway. As the local coalfields closed, the

pits at Cannock responded to increased demand and so Highbridge and Ryders Hayes Junction became a

marshalling yard for coal trucks from the Cannock pits.

By the 1920s and 1930s the junction had become extremely

busy and so was a prime target in World War 2 for German

bombers, in an attempt to cripple coal supplies to

Birmingham and Coventry. They were attacked in a bombing

raid, but the bombs missed their target and destroyed a

house in Highbridge Row. Luckily there were no injuries.

The Row was demolished in 1964.

Brownhills Railway Station

closed in 1965 as a result of the Beeching Report,

although the line continued to be used for goods until 1983.

The track bed is still in use today, for leisure. In

2000 the section from Walsall to Pelsall became part of

the Sustrans National Cycle Route and in 2018 it became

part of the 'McClean Way' named after John Robinson

McClean.

|

|

Looking towards Station

Road in the early 20th century. From an old

postcard. |

|

As the population increased in

the 1860s, affordable houses were built at Heath End and

in Wood Lane, and the first shops were built in Norton

Road, which supplied the villagers with their every day

needs, including food, clothing, and household goods.

The wealthier members of society had houses built in

Chapel Place (now Chapel Street) and later in Ashtree

Road.

In the 1860s and 1870s Heath End

rapidly grew due to the establishment of a brickworks

and two collieries in the area. This led to the building

of back to back terraces around Princess Street that

stood between Walsall Road and Victor Street. They

suffered from poor sanitation and a crude water supply,

having just a single communal tap that supplied water to

20 or 30 houses.

The population of Pelsall in 1851

was 1,132, which had grown to 2,928 in 1881. Around

1885, Miss Hussey of Wyrley Grove opened a free lending

library and a night school in Highbridge (now Lichfield

Road) and closed the Railway Colliery Hotel. She had it

converted into houses and improved the adjacent

buildings.

By the 1890s, Pelsall’s shopping area was

well developed. The 1891 census lists the following

shopkeepers and their shops in Norton Road:

William Clark, grocer; William

Gilbert, butcher; Ernest Haldane, draper; James

Harrison, hairdresser; Richard Lane, greengrocer; Moses

Palmer, tailor; Edward Sluter, the postmaster; Harry

Smith, druggist; Edward Trimingham, chemist; and Joseph

Williams, stationer and picture framer.

By 1891 the local population had

grown to 3,364. Pelsall Parish Council was formed in

1894, and three years later took over the care of the

common land. By the end of the century the village had

become almost self-sufficient; with its local council,

shops and amenities, and an identity of its own.

|

|

Norton Road. From an old

postcard. |

|

Churches and Chapels

The earliest known church in the village was in

Paradise Lane, near to Pelsall Hall. The church, known

as St. Peter’s, had an area of land that was farmed to

fund a priest. The land had been given to the church by

William de Keu in 1311. During the short reign of King

Edward VI (1547-1553), an attempt was made to introduce

the Protestant faith to England, based on churches in

Switzerland and Germany. During the campaign, churches

were inspected to determine the value of property and

goods, and Catholic trappings were taken away. When

Pelsall church was inspected, the plate and vestments

were removed by Richard Forsett, and only the two church

bells in the steeple were left.

The roof of St. Peter’s Church collapsed in 1762, and

in 1763 the church was rededicated to St. Michael and

All Angels. On the 7th November of that year, the first

burial took place in the new graveyard next to the

church in Paradise Lane. The first person to be buried

there was Edward Wiggin. The old graveyard can still be

seen today, next to Pelsall Hall. The site has been

tidied and grassed-over, but a few of the old headstones

have survived. They have been placed against

the brick wall on the left-hand side of the site, next

to the drive that leads to the hall. Stebbing Shaw

describes the church as 'small and ancient' in his

'History and Antiquities of Staffordshire' published in

1801. The half-timbered vicarage was further along

Paradise Lane and had a thatched roof.

The church could only seat 174

people and so was too small to cope with the growing

population. The decision was taken to build a larger

church in the village that could seat around 600 people.

The foundation stone for the new church in Hall Lane was

laid on 7th June, 1843 and building work was completed

in the following year. The new St. Michael and All

Angels Church was built of plain brick, and initially

had no tower. When the church opened, the old church in

Paradise Lane was demolished. The church tower, built

some years later, was a gift from Mrs. Sarah Dickenson,

who provided the clock and a peal of five bells. A sixth

bell, added in 1920 was a gift from Mrs. J. S. Charles.

In 1848 a vicarage was added at a cost of £1,000, but

this fell into a state of disrepair and was demolished

in 1980. The chancel was added in 1889 and a new organ

was installed.

The first Methodist chapel in the

village opened at Heath End in 1830. It was replaced by

a new building in 1869, but was never a great success.

The trustees were often faced with bills from costly

repairs, especially in 1905-6 when the cost of

renovation work amounted to £103.13s.10½d., a

considerable sum at the time. A pipe organ was also

installed at a cost of £50. The congregation dwindled in

the late 1940s when the old houses at Heath End were

demolished and the people were re-housed elsewhere. The

chapel closed in 1959 and was soon demolished.

In 1836 another Methodist chapel

opened in Station Road, after a petition had been sent

to the local authority, stating that although the local

population was rapidly increasing due to the growth of

ironworks and collieries, there was no provision for

education. If permission could be granted for the

building of a chapel, a school for children of all

denominations would also be built on the site.

Joseph Fletcher, an inspector of

schools was sent to Pelsall to investigate, and reported

that due to the poverty of the poor nail makers and

miner population of this remote neighbourhood, nothing

but extraneous aid will ever meet their case. Thanks to

his report, permission was given for the building of the

chapel and a school, which were built for £260. In 1858

the school came under Government control and received

its first certified teacher in January 1859. The

Wesleyan chapel and the school were a great success, so

much so that they couldn’t cope with the demand.

|

|

St. Michael and All Angels Church

in Hall Lane. From an old postcard. |

|

A larger Wesleyan Methodist chapel

opened in Chapel Place (now Chapel Street), on 14th

July, 1858. It was largely funded by Boaz Bloomer who

ran the Pelsall Coal and Iron Company. He supplied the

land on which the church was built and contributed £750

towards the building of the minister’s house. He was

made church treasurer, and his son, Ben Bloomer, was

church organist.

Boaz Bloomer also gave £1,000

towards the building of the replacement school, which

opened in 1866 in Chapel Street. Boaz became Sunday

School Superintendent. The school was enlarged in 1895

and continued as a day school until the mid 1960s.

The chapel was renovated in 1904 at

a cost of £660, and survived until demolition in 1970.

By this time the chapel had taken over the old Wesleyan day school and

amalgamated with the worshipers from the Primitive

Methodist Chapel in Paradise Lane, which had opened in

1853. A large extension was added to the church in 1970,

which is now known as Pelsall Methodist Church.

The old chapel in Station Road,

became known as Central Hall and remained in use as a

community centre. The Mutual Improvement Society had a

reading room in the building, and the Wesley Guild, the

Pelsall United Friendly Society, and the Parish Council

held meetings there. In 1923 a concert and a billiards

room opened in an extension at the back of the building,

and the hall became the headquarters of the local A.R.P.

wardens in the Second World War. It has now been

demolished.

Education

Some of the older inhabitants

remembered a Dame School and a Poor School in the

village that charged 4d and 1d per week, respectively,

for lessons. Although the Employment Act of 1842

prohibited children under 10 years of age, from working

in the mines, many families could not afford the education

fees.

In 1845 St. Michael and All Angels

Church applied to the National Society for a grant

towards the building of a National School, which could

cater for 133 pupils, with a residence for a master. A

site for the school was provided next to the graveyard.

The estimated cost of the school was £432.4s.7d., which

included the £95 grant from the National Society and

£110 that was given locally. Pelsall National School

opened in about 1848. In 1865 there were 180 pupils

being taught in one room by a master and a mistress.

Large numbers of children started at the school from the

age of three, which led to an acute shortage of

accommodation. In 1870 the room was divided into two

smaller rooms by sliding doors.

In 1881, after the passing of the

1880 Education Act, which led to compulsory education

for 5 to 13 year olds, a new boys’ school was built

alongside the existing premises to accommodate 230

pupils. Free schooling did not happen in the village

until 1891, before which, a two pence a week fee was

charged for each pupil. Another room was added in 1891,

and in 1895 there were 395 pupils. In 1907 the school

became Pelsall Church of England School.

In 1916 the infants were moved to a

new council school in School Lane and in 1931 the

original school building was demolished to make way for

a new infants block. In December 1965 most of the staff

and pupils moved to the new school that opened in Maple

Road in 1961. The old school continued in use as an

annexe until 14th December, 1977.

|

|

Station Road. From an old

postcard. |

|

Into the Twentieth Century

In 1901 the population was 3,626

and more shops opened, in order to keep pace with

growing demand. In High Street in 1908 the shops were

occupied by shoe makers, bakers, a grocer, a tailor, and

a beer seller. In 1909 gas mains were laid in the

village, and in 1924 electricity cables were added. The

village’s first regular bus service to and from Walsall

began operating in 1925, and in 1934 Pelsall came under

the control of Aldridge Urban District Council.

|

|

The Swan Inn, Wolverhampton

Road. |

By the 1950s there were many

run-down and dilapidated houses in the village and so

the local authority started a slum clearance programme.

In 1952 Pound House in Paradise Lane was demolished. It

stood next to the village pound where the stray animals

were kept. Other demolitions at the time included the

old chapel, the old vicarage, and Paradise House in

Paradise Lane, which had been a large house with a

picture of Adam & Eve above the front door. Another

casualty was a row of terraced houses known as Slate

Row, in Church Road. They had once been occupied by nail

makers, ironworkers and miners, and in 1895 a resident

died from typhoid. There were also several cases of diphtheria.

Another casualty was Pelsall Farm,

a large three storey building off Charles Crescent with

a cottage attached. It had twelve acres of land,

including meadows and two ponds with ducks and geese.

In

1952 the council purchased the estate from Mrs Wallace

of Little Wyrley Hall for £2,000 and rented the land to

a local farmer.

In 1964 the site was redeveloped for

housing and Charles Crescent was built on part of the

site. |

|

Oaklands House was a large house in

Station Road that had been owned by the Binns family,

and previously by Thomas Starkey, when it was known as

Victoria House. In 1956 Aldridge Urban District Council

purchased the house and grounds for £3,000. The grounds

were sold for redevelopment in 1962 and the house was

demolished and replaced with the Pelsall Community

Centre building, which is there today. The Pelsall

Community Association, which is based at the community

centre, was formed on 1st July, 1946 to serve the local

community. The community centre was officially opened by

Sir Alfred Owen, CBE. on 4th September, 1965. In 1974

the building was extended when the Oaklands Lounge & Bar

were added. Activities at the centre include adult dance

sessions, keep fit classes, Taekwando, ladies'

kickboxing, art classes, embroidery classes, and mother

and toddler sessions. The site includes a bowling green

and tennis courts.

There were several working farms in

the area until the late 1940s, but most of the land has

now been used for housing development. In the 1960s a

large number of council houses were built on the Ryders

Hayes Estate between Ryders Hayes Lane and Railswood

Drive, and in 1970 much of the old housing and the New

Inns pub near the end of the old Gilpin Arm were

demolished and replaced by the modern estate. The pub

began life as a beer shop and afterwards became the

headquarters of the local pigeon flying club. By 1940 it

had become a general store.

In 1966 Pelsall became part of

Aldridge and Brownhills Urban District Council, and on

1st April, 1974 it became part of Walsall Metropolitan

Borough Council, which was formed following a local

government reorganisation.

The old fingerpost at the junction

of Norton Road and Lichfield Road still remains, after

being restored in the 1980s by Bert Kellitt, for the

local Civic Society. Pelsall also has a Millennium

Stone, marking the 1994 millennium of the village. Since

July 1972 Pelsall has had an annual carnival which was

originally a week-long event. It is very popular and

features decorated floats, many outdoor events on the

common and indoor events at the community centre.

The Pelsall bus in the old Walsall

bus station.

The main shopping area around Norton Road and High

Street continues to thrive. There are card and gift

shops, dry cleaners, estate agents, fish and chip shops,

flower shops, food shops, hairdressers, The Queens pub,

and much more.

The population is now over 11,000. It is listed as

11,505 in the 2011 census. A valuable asset to the local

people is Pelsall Village Centre, in Highfield Road,

which opened in 2012. Sadly Pelsall Library which was based

there, closed in 2017 as part of Walsall Council’s

cost-cutting plans. Luckily a team of volunteers now run

the Pelsall Book Exchange there, where people can sit in

comfort to read books, or borrow them.

Pelsall is still a very pleasant

place to live, partly because the open areas have been

well protected and preserved over the years. The North

Common Local Nature Reserve is an important asset,

consisting of wet heathland and a wonderful variety of

wildlife from butterflies and bees, to many species of

birds and mammals.

|

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|