|

Possibly the most famous trial in

Walsall’s history is that of the Walsall anarchists in 1892.

It involved a revolutionary organisation, a secret bomb

factory, and police informers.

It all began in the summer of 1891 when

four foreigners arrived in the town from London, looking for

work. They were Victor Cailes, his partner Marie Piberne,

Frederick Charles, and George Laplace. Victor and Marie

found lodgings at 54 Green Lane, while Frederick and George

moved into 272 Green Lane, the house and workshop of William

Ditchfield. Another person involved in the plot was Joseph

Deakin, a railway clerk who lived above a draper’s shop at

238 Stafford Street. He was one of the founders of the

Walsall Socialist Club, a branch of the Social Democratic

Federation whose members were extreme socialists, greatly

influenced by the writings of Karl Marx. The club was based

in a rented house at 18 Goodall Street which had been

procured by one of the members, John Wesley, who had a

brush making business next door at number 17.

This was a time of political unrest,

most prominently demonstrated by the Irish Nationalists who

had been planting bombs in England. Bombs were also planted

by other revolutionary groups known as anarchists, who at an

international conference in 1881 at Brussels announced their

intention to use the dagger, the gun, bombs, and dynamite to

promote their cause.

Local police forces were quite rightly

interested in the activities of such groups and kept a close

eye on them. Walsall’s Chief Constable, Christopher Taylor

had been keeping a close watch on the activities of the

Socialist Club and became concerned about the presence of

the four foreigners. At the time many European immigrants

were political refugees who brought their political beliefs

with them, and so their presence in Walsall set alarm bells

ringing.

The police had informers within the

anarchist movement and so the Chief Constable turned to them

in an attempt to discover what was going on. Aguste Coulon,

a London-based anarchist and police informer mentioned that

bombs were being manufactured in Walsall, which led to a

visit by Inspector Melville from London. He informed the

Chief Constable that Jean Battolla, a flamboyant Italian was

about to visit the town, and so the police kept a lookout

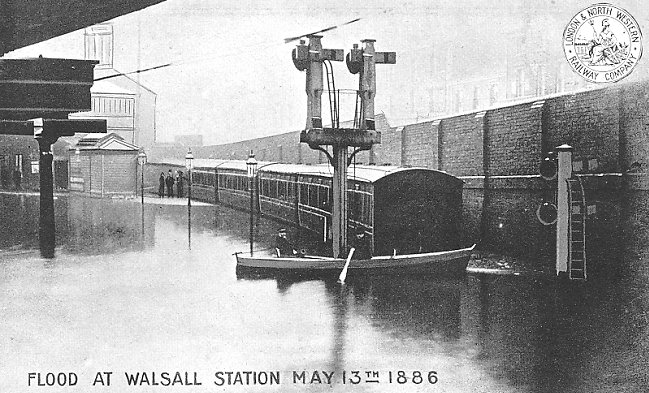

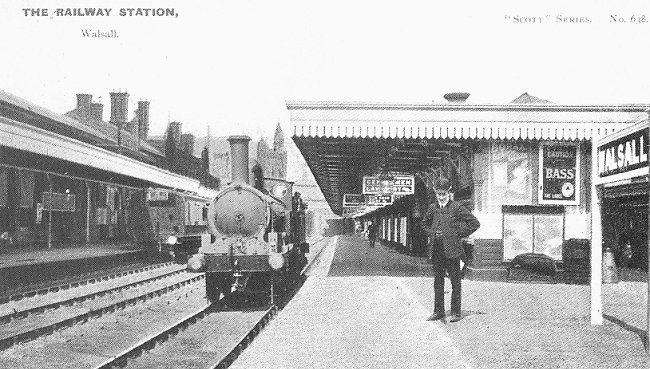

for him. Two police officers Taylor and Melville were on

duty when Battolla arrived at Walsall railway station. They

followed him to the Socialist Club, and then followed him

when he left to go to William Ditchfield’s house in Green

Lane with Victor Cailes and Marie Piberne. They then

followed the group back to the Socialist Club and continued

their vigil until their watch ended at 8 p.m.

By this time they had observed Joseph

Deakin, Frederick Charles, and John Wesley going in and out

of the club several times. Afterwards Sergeant Cliffe took

over the police watch until Taylor and Melville returned the

following morning. Battolla stayed the night in Walsall, and

his activities, and those of the club members were noted. In

the afternoon they followed Battolla, Wesley, and Charles to

the railway station where Battolla caught the five twenty

train to London.

On 6th January, 1892 Joseph Deakin went

to London, where he was arrested for refusing to explain why

he was in possession of a bottle of chloroform. Battolla was

also arrested.

Back in Walsall the police jumped into

action. On 7th January, Christopher Taylor and Sergeant

Cliffe questioned William Ditchfield at his house in Green

Lane and removed a plaster mould, and lead and brass bolts.

They took Ditchfield into custody for further questioning.

They then visited the Socialist Club and arrested Charles,

Cailes, and Marie Piberne. They took away more moulds, a

length of fuse, a mixture of plaster and horsehair, and some

anarchist literature. At the time John Wesley was away, but

he was arrested on his return to the railway station.

Deakin and Battolla were brought from

London, and the whole group was held in the cells beneath

the Magistrates Court. Marie Piberne was quickly released,

but the others continued to be held until they could appear

before the local magistrates, which they did on 21st

January.

During the proceedings the Chief

Constable stated that when Charles was arrested he was in

possession of a loaded revolver, ammunition, and a

sketch of a bomb. He also said that on the night of 15th

January he had been given a statement written by Deakin

stating that the chloroform had been taken to London at the

request of Frederick Charles. The Chief Constable also

stated that Deakin was later interviewed by Inspector

Melville. During the interview Deakin stated that Charles

was a police spy. He then supplied Deakin with paper to

write a second statement. In the statement he stated that he

and his comrades had been making bombs, and that the idea

had originated in a letter to Charles from someone at the

anarchist club in London. He believed the bombs were to be

used in Russia against the tyrannous regime of the Czar.

Colonal Ford, a Home Office explosive

expert gave evidence about the moulds. He stated that they

could be used to produce the casing for a bomb if they were

slightly adjusted during moulding, but admitted that he

would not have thought them to be suspicious if it hadn’t

been suggested beforehand. He also said that the fuse was

not suspicious, being just ordinary miner’s fuse.

Evidence was given to show that on 23rd

November, 1891 the moulds had been sent to Mr. Bullows, an

ironfounder in Long Street to ask for a quotation for some

castings. He unsuccessfully tried to produce samples, but

there were problems with the mould. The police later asked

him to try again, and this time he was successful after

slightly altering the mould. It hadn’t occurred to him that

the castings might be for bombs.

Several other experts gave evidence,

and all six men were committed for trial at Stafford

Assizes.

The trial took place on 30th March,

1892 before Mr. Justice Hawkins, and the Attorney General,

Sir Richard Webster, Q.C. in the Crown Court Room at

Stafford Shire Hall. The defendants were charged with two

offences under the 1883 Explosive Substances Act:

1. That between 1st November,

1891, and 7th January, 1892 at the Borough of Walsall, with

being in possession of explosive substances for unlawful

purpose.

2. That between 1st November,

1891, and 7th January, 1892 they unlawfully conspired

together to cause by explosive substances, an explosion in

the United Kingdom.

The evidence was much the same as had

already been given at Walsall. None of the defendants gave

evidence. After a short trial Charles, Cailes, and Battola

were sentenced to ten years penal servitude, and Deakin to

five. Ditchfield and Wesley were acquitted.

After the convictions many socialist

campaigners believed the whole thing was a police plot. A

London journalist called Nicholls was imprisoned for making

speeches, and publishing pamphlets in which he stated that

the men were framed by police spies, notably Aguste Coulon.

After the trial Walsall Council

presented Chief Constable, Christopher Taylor with fifty

pounds for his efforts in the case. It had been rumoured

that the Czar of Russia presented him with a diamond tiepin.

It is not known what happened to Wesley, Ditchfield, Cailes,

and Battolla, but Joe Deakin returned to Walsall and

continued his socialist work. Frederick Charles married

twice, and became involved in socialist agricultural

experiments. He died in Oxfordshire in 1934.

The episode leaves a lot of unanswered

questions. Were the castings really for bombs? If so where

were they to be used? Did the police simply over react?

|

The

Walsall Anarchists (1892)

From

the Walsall Free Press and South

Staffordshire Advertiser. April 1892.

In January, 1892, five

men who lived in Walsall and one who lived

in London, were arrested on charges of being

in possession of explosive substances for an

unlawful purpose and conspiring to cause an

explosion in the United Kingdom of a nature

likely to endanger life or to cause serious

injury to property, under the Explosives Act

of 1883.

The prisoners were:

| Frederick

Charles |

(27) |

57 Long Street,

Walsall |

Commercial Clerk |

| Victor Cailes

(French ) |

(33) |

18 Goodall

Street, Walsall |

Railway man |

| John Wesley |

(32) |

17 Goodall

Street, Walsall |

Brush Maker |

| William

Ditchfield |

(40) |

272 Green Lane,

Walsall |

Hand Filer |

| Joseph Thomas

Deakin |

|

238 Stafford

Street, Walsall |

Railway Clerk |

| Jean Battolla

(Italian) |

|

Charlotte

Street, Soho, London |

|

Joseph Deakin was one

of the founder members of the Walsall

Socialist Club which met at 18 Goodall

Street, Walsall. He had represented the

United Kingdom at an International

Anarchists Conference in Brussels where he

had met Cailes, Battolla and Aguste Coulon,

member of the Autonomie Club group of

Anarchists. Cailes was wanted by the French

police and he came to Walsall where Deakin

helped to find him a job.

The case was first

brought before the Walsall magistrates and

the prisoners all complained about their

treatment, accommodation and food. 'The

Chief Constable admitted that the prisoners

were only given enough food to keep them

alive'.

It later emerged that

one of the prisoners had been woken up and

cross examined in the middle of the night

and been offered whisky and cigars as an

inducement to make a statement. However, a

subsequent enquiry by the Walsall Watch

Committee as to the treatment of the

prisoners whilst in custody at Walsall,

exonerated the Chief Constable Christopher

Taylor, and as subsequent documents

illustrate he was rewarded by the Treasury

for his efforts.

On February 16th, 1892,

the case was transferred to Stafford

Assizes, although the trial did not begin

until March 30th. The case came before Mr.

Justice Hawkins and the Attorney General

(Sir Richard Webster, Q.C.) who led the

prosecution for the Crown. The prisoners all

pleaded not guilty and it does appear from

the evidence that Aguste Coulon, an

anarchist based in London had acted as an

agent provocateur for the police. However,

evidence was also given at an attempt to

manufacture explosive devices, although this

was unsuccessful. A number of Anarchist

pamphlets, found at 18 Goodall Street, were

also read out in the court, which appeared

to threaten a bombing campaign. The

prisoners claimed that most of this

literature had been planted by the police.

In April 1892, the jury

found Charles, Cailes, Battolla and Deakin

guilty. Wesley and Ditchfield were

discharged. The Judge sentenced Charles,

Cailes, and Battolla to ten years penal

servitude and Deakin to five years penal

servitude.

Many socialist and

labour clubs throughout the country

campaigned against the sentence, believing

the whole thing to be a police plot. |

|

|