|

In the 19th century the population of Walsall rapidly

grew, as people moved into the area looking for employment

in the expanding industries. Within 40 years the population

had doubled, and doubled again in the next 25 years. By the

end of the century the population had increased almost nine

times to nearly 90,000, which would have been unimaginable

in 1800.

|

Population |

| 1801

|

10,399 |

|

1811 |

11,189 |

| 1821 |

11,914 |

| 1831 |

15,066 |

| 1841 |

20,852 |

| 1851 |

26,816 |

| 1861 |

39,692 |

| 1871 |

48,529 |

| 1881 |

58,802 |

| 1901 |

86,400 |

A New

Post Office

Around 1800 a new post

office opened on The Bridge. It had previously been in

the Bull’s Head Yard in Rushall Street, and is believed

to have been the town’s first post office. In the early

1800s the postmaster was Mr. Hill, who was assisted by

Mr. Bullock, the postman for the Borough who earned

seven shillings a week. When he delivered letters past

the pinfold he received an extra penny, and an extra two

pence for deliveries over a mile. Letters to the Foreign

were delivered by the postmistress, Mrs. Bullock. In

1813 the revenue for letters coming into the town was

estimated at £2,000 per year. The post was received at

11 o’clock, and the postal charges for letters were as

follows:

To London

- ten pence. To Lichfield - five pence. To

Birmingham - four pence.

In 1827 the post

office moved to Digbeth, with an entrance in Adam’s Row.

It remained there until around 1853 when it returned to

The Bridge, from where it moved to Park Street. In 1879

a new and much larger post office was built on the

corner of Leicester Street and Darwall Street.

Libraries

Walsall’s first public

library opened on 14th November, 1800 in Rushall Street.

It was founded by the Rev. Thomas Bowen, a Unitarian

minister, at his own house, and available to anyone on

the payment of a subscription. He provided a library

room, and a librarian. Bowen published several

educational books, and invented a number of mathematical

instruments. Around 1813 the library moved to a larger

room at Valentine and Throsby's stationery shop in High

Street.

|

| By 1830 there was a need for a larger

library. A public meeting was held on 16th August, 1830

which led to the building of St. Matthew’s Hall in Lichfield

Street which contained a reading room containing around

3,000 books, a news room, and a first floor gallery.

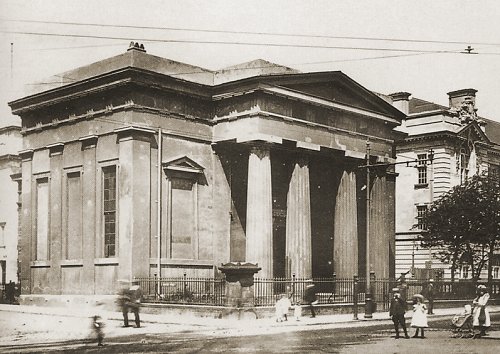

The stuccoed building, on the corner of Leicester Street

was built in 1830 and 1831 in brick and stone, to a Greek

Doric design, with a large portico supported by four

columns. It cost 1,600 guineas to build, raised by a sale of

shares costing £10 each. |

St. Matthew’s Hall. From an old

postcard. |

|

An earlier view of St. Matthew's Hall. |

Unfortunately the subscription proved to be too high,

and the library closed.

The building remained empty for

several years until it was purchased in 1847 by Mr. C. F. Darwall, Clerk to the Magistrates, for £620.

It was

initially used as a savings bank, until around 1855 when the

ground floor became the County Court, and a lecture room.

The first floor was used as a freemason’s hall, and also for

musical entertainment. |

|

The County Court

continued to be held there until the 1990s when it moved to

Upper Bridge Street. The building then became a bar, a

restaurant, a night club, and is now a Wetherspoons pub.

When the library and news room closed

in St. Matthew’s Hall, they were moved to John Russell

Robinson's printing works on the Bridge, where a literary

and philosophical institution was added, where lectures and

discussions were held.

In 1857 Walsall council decided to open

a library under the terms of the Free Libraries Act of 1850,

which gave local boroughs the power to establish free public

libraries. In 1859, a library building, designed by Nichols

& Morgan in a Renaissance style, was built in Goodall

Street. In 1872 the Free Library was converted to a news

room, and a library with a reading room above. Three years

later the books and papers from the library at Robinson’s

printing works were presented to the Free Library when the

subscription library closed.

In 1887 the Free Library was extended,

and in 1890 the upper room became the art gallery, museum,

and reference library. It was replaced in 1906 by a new Free

Library in Lichfield Street. The old free library building

still survives today as shops. |

The Free Library. |

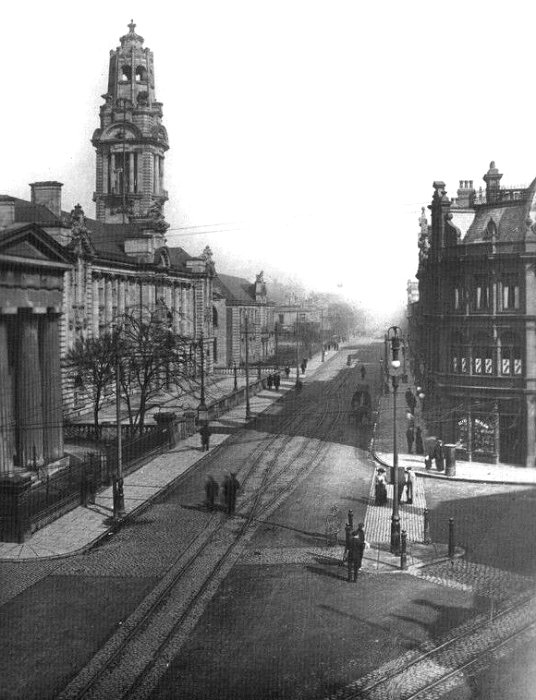

Walsall's second Free Library in Lichfield

Street. From an old postcard.

The new Town Hall.

|

Theatres

Until the early 19th century, most of

the entertainment in the town was provided by travelling

groups of players, in various halls and assembly rooms, the

most popular being at the Dragon Inn in High Street, which

had a stage, but no scenery.

|

| Walsall’s first purpose-built theatre

opened on the eastern side of the Old Square, just off

Digbeth, in 1803. It was built by

subscription, for which fifty pound shares were available. Each subscriber received interest on his investment, which

on paper looked good, because the takings for a full house

could average between fifty and sixty pounds.

Although

several well-known actors performed there, the venture was

not a success, and it closed in the early 1840s.

In 1845 the

proprietors were evicted for non-payment of rent, and a few

years later the building was converted into shops. |

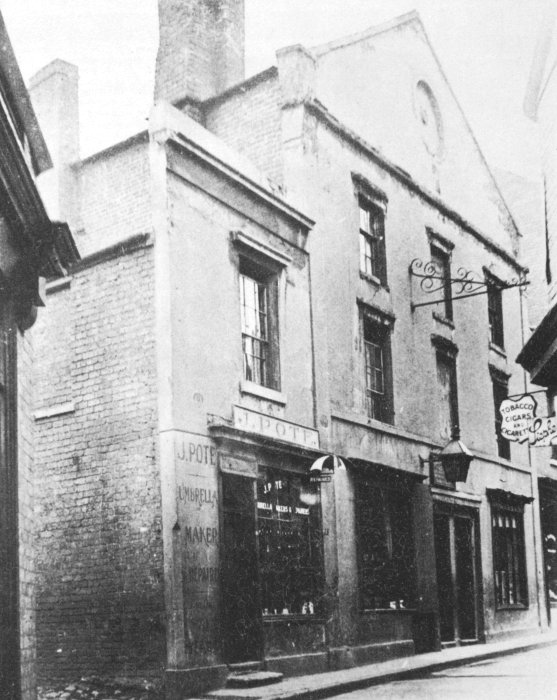

Walsall’s first purpose-built

theatre after it was converted into shops. |

|

|

In 1839 Samwell’s Circus Royal was in

Goodall Street, and in the early 1840s Holloway’s Theatre

opened at Bloxwich racecourse. Productions included popular

plays and musical performances. The theatre moved to

Walsall, and was replaced at Bloxwich by Bennett’s Theatre.

Until the building of the Agricultural

Hall in 1868, entertainment was again mainly confined to

travelling companies and amateur groups, appearing in halls

and assembly rooms such as the Temperance Hall in Freer

Street, and the Guildhall Assembly Rooms in Goodall Street.

The Agricultural Hall was built on The Bridge opposite St.

Paul’s Church in what is now Darwall Street, and sponsored

by leading local farmers, millers, and grain dealers. It

could seat up to 1,000 people, and acquired a theatrical

licence in 1871 after which operatic and dramatic

performances were held. It opened as a permanent theatre on

26th March, 1883 and was run by Rebekah Deering who rented

the building. Unfortunately it was unprofitable, and

suffered the same fate as the Old Square Theatre. After

changing hands several times it was sold in 1885 to become a

public hall, known as St. George’s Hall. It reopened on 22nd

September, 1887 with an increased seating capacity of 1,500,

and was used for a time as a music hall. From around 1895 it

became known as St. George’s Theatre.

In the late 1890s it was rebuilt as the

Imperial Theatre by the Walsall Theatres Company whose

Secretary and Manager was William Henry Westwood who had a

great influence on the local theatres.. It

reopened on 22nd May, 1899 with a seating capacity of 1,600.

The new theatre only operated for around a year because the

company was already building Her Majesty’s Theatre at the

top of Park Street. The Imperial Theatre became Walsall's

first cinema in 1908, and screened its last film in 1968. In

1974 it became a bingo hall, and until recently a Wetherspoons pub.

It is Walsall’s last surviving theatre building from the 19th

century. |

|

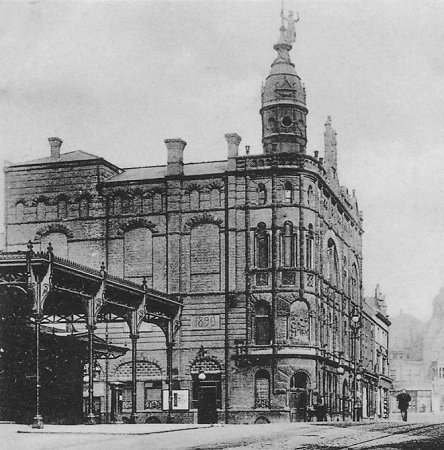

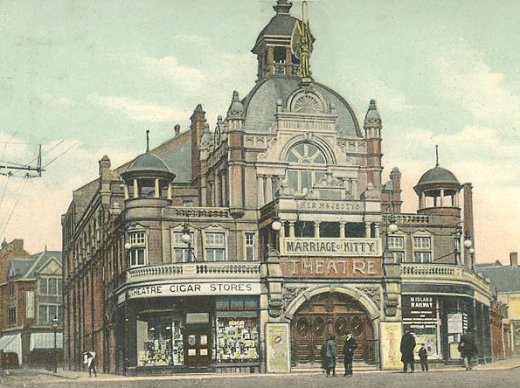

The Grand Theatre. From an old

postcard. |

Around 1870 Charles Crooke opened

Crooke’s Music Hall in his former beer and wine shop on the

corner of Park Street and Station Street. It became known as

the Alexander Theatre, until 1886 when it changed hands. The

new proprietor, William Henry Westwood changed its name to the

Gaiety Theatre.

In 1890 it was replaced by the ornate

Grand Theatre, built to the design of Daniel Arkell of

Birmingham.

It had a cupola on which stood a gilded

lady with a trumpet, and a niche containing another gilded

lady playing a lyre.

It cost £14,000 to build, and had a

seating capacity of 2,000, but like the other theatres was

financially unsuccessful, which led to its closure in 1899.

|

| Many famous acts appeared there including Vesta Tilley, the

gymnasts Volti and Ray, the comedian Frank Seeley, and the

Villion Troupe cycling act. A ticket for the gallery cost

six pence, but a ticket for the dress circle was priced at

two shillings, a lot of money for most people at the time. On 4th September, 1899 it was

officially reopened by Vesta Tilley as the Theatre of

Varieties, and became known for variety shows, silent films,

and drama. It became a cinema in 1931 after Associated

British Cinemas acquired the building. It remained in use

until 1st October, 1938, when it closed. After being

acquired by the grandson of the mayor, Pat Collins, it

reopened as the new Grand Theatre, but disaster struck on

6th June, 1939 when it was completely destroyed by fire.

Her Majesty’s Theatre Walsall’s most

successful theatre, Her Majesty’s Theatre, opened in 1900

and was built of brick and stone in French Renaissance

style, with a large copper dome on the roof and a tall

flagpole. The theatre stood at the top of Park Street on one

of the most prominent sites in the town, which had been

earmarked for the new Town Hall, until the council decided

to build it in Lichfield Street. It formed an impressive sight as seen from Park Street, and had a

lavishly decorated interior with fine ornamental

plasterwork, electric lighting, and a grand hall, paved with

a marble mosaic. The stage was 75 feet long and 45 feet deep

so that it could accommodate the most elaborate scenery and

the largest companies. It could seat over 2,000 people, and was known for its

high class dramas which were initially successful. |

| It was

owned by the Walsall Theatres Company who engaged Owen &

Ward of Birmingham, a firm of specialist theatrical

architects to design the theatre, which was built by

Whittaker & Company of Dudley. The theatre was formally

opened on Saturday 24th March, 1900 by the Mayor of

Walsall, Councillor J. W. Pearman-Smith, and a large

number of guests. They saw a short musical, and enjoyed

a lavish tea. The theatre opened to the general public

on Monday 26th March with a musical comedy called 'The

Belle of New York' which was performed by the Ben Greet

Company. Tickets cost 6 pence and 9 pence for a seat in

the gallery, and one guinea for a ticket to a private

box. A varied programme of music, drama, and variety

became the norm. In 1903 the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

performed 'The Mikado', 'H.M.S. Pinafore', and 'The

Yeoman of the Guard'. In 1906 Lily Langtry performed at

the theatre, and Harry Lauder topped the bill in 1908.

Sadly audiences started to decline, mainly due to

competition from theatres in Birmingham, and so Her

Majesty's turned to vaudeville, before becoming a cinema

in 1933. |

| In 1935 the building was acquired by Associated British

Cinemas (ABC), but the cinema was not a great success.

Audiences of the day did not appreciate the elegant

Victorian interior which was considered to be unfashionable.

The cinema closed on 5th June, 1937 and was demolished to

make way for the Savoy Cinema, later known as the A.B.C. In

the process, Walsall lost one of its most elegant buildings,

but no one seemed to care. There was no public outcry,

people were happy to see it go. |

Her Majesty’s Theatre. From an old

postcard. |

Her Majesty's Theatre in May 1936.

| |

|

View a couple of

early 1930s

programmes for productions

at Her Majesty's Theatre |

|

| |

|

From the 1899 Walsall Red Book.

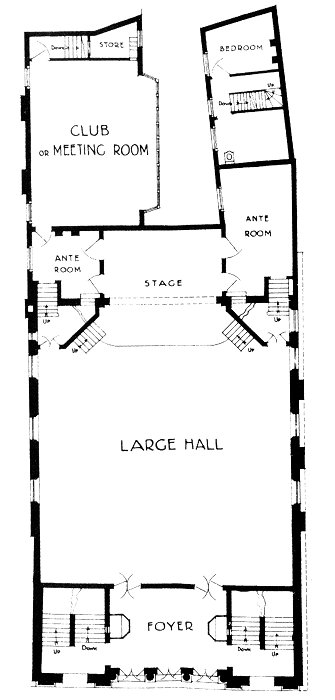

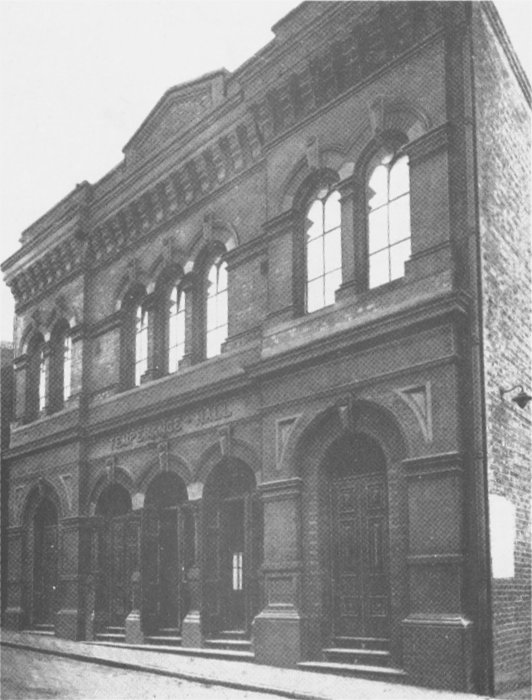

| The Temperance Hall and The

Empire |

|

In the mid 19th century

the temperance movement rapidly grew. In

1855 a temperance society was formed in

Walsall with the aim of reducing the poverty

and misery caused by the excessive

consumption of alcohol. The Temperance

Society purchased a piece of land in Freer

Street in1866, for the site of a temperance

hall, which would offer alternative forms of

entertainment to the public house, to make

people less dependent on alcoholic drinks.

The land was acquired

for £500 and a temperance hall was designed

by local architects, Loxton Brothers of

Wednesbury. The building, which took 9

months to build, cost £1,970, and was paid

for by public subscription. It was built in

the Italian style, of red brick, with

dressings of Bath stone and Portland cement.

The main entrance in Freer Street was via a

foyer with three pairs of swing doors.

The hall covered

an area of 65ft. by 45ft. and could

accommodate around 1,000 people on pine

seats on the floor and on a horseshoe shaped

gallery, which ran around three sides of the

hall. The hall ceiling was lavishly

decorated and well lit, with 5 gas

chandeliers, and side and front windows. At

the far end was the stage.

The building also

contained two reading rooms, two dressing

rooms, a lantern slide and film projection

room, a committee room, a dance hall on the

lower ground floor and cellars. Hall

keeper's residence rooms were also included

at the back.

The building, which

opened on the 2nd February 1867, was let for

religious, philanthropic and charitable uses

that were in keeping with the principles of

the Temperance Society. Each Christmas the

hall was opened for the ‘Robins' Breakfast’

for the poor children of the town, who each

received a packet of sweets, an orange, an

apple and were allowed to play games in the

hall. |

The ground floor plan

of the Temperance Hall. |

|

The Temperance Hall. |

On Saturday nights popular entertainment

was organised by musical or dramatic

societies. One of the first regular uses was

for a series of lectures organised by the

Walsall Literary Institute. The hall became

very popular and was in use most evenings.

In 1892 and 1893 the hall was used for

church services after the old St. Paul's

Church was demolished, until the new church

opened.

The hall was known for its excellent

acoustics and many celebrities performed

there including Oscar Wilde, who spoke on

'The House Beautiful' in 1884.

The first ever moving pictures seen in

Walsall were shown there by Mr. Shrapnel,

but the quality was very poor. |

| After the bombing of Wednesbury Road

Congregational Church, during the Zeppelin

raid on the 31st January, 1916, church

services were held in the hall until the

church had been repaired. |

| In June 1917 a Food Economy

Exhibition was held there, organised by

the Food Control Campaign Committee in

the hope of promoting new ideas to

housewives to help overcome the

shortages caused by the war. Things

went badly wrong on the 21st October,

1921, during a concert. A ceiling

support beam collapsed and part of the

ceiling fell onto the audience. One

person was killed and many were injured.

Expensive repairs were required and the

hall lost much of its former popularity.

The premises were

eventually put up for sale in May 1930

at the Grand Hotel in Birmingham and

sold for £13,500 to a Mr. T. Jackson,

from Bournemouth, who converted it into

a cinema. Before work began on the

cinema, a farewell meeting was held in

the hall during which Alderman Joseph

Leckie, referred to the days when the

Temperance Hall was at the height of its

success.

The new cinema,

called ‘The Empire’ was designed by J.

H. Hickton. The building work was

carried out by J & F Wootton of Bloxwich.

The original facade

was covered with white cement and new

entrance doors replaced the old swing

doors. A new floor was also installed,

together with upholstered seating for

1,200 people in the stalls and balcony.

The cinema opened on Monday 28th August,

1933 with a showing of the musical

comedy ‘Letting in the Sunshine’.

In 1937 The Empire

was sold for £20,000 to Captain Clift to

become part of the Clifton Circuit.

In 1954 it was

Walsall’s first town centre cinema to

install cinemascope, which was extremely

popular and resulted in long queues

forming in Freer Street, particularly

for each performance of 'The Robe'. The

last film to be shown there was

‘Cleopatra’ on the 24th October, 1964.

In February 1965

the cinema was demolished to make way

for the Old Square Shopping Centre. |

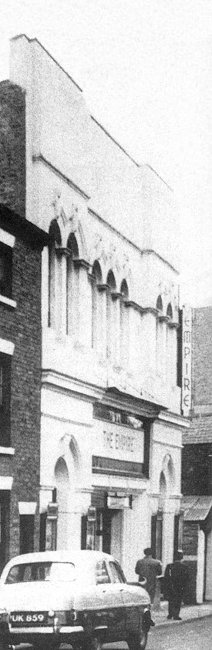

The Empire. |

The location of The Empire.

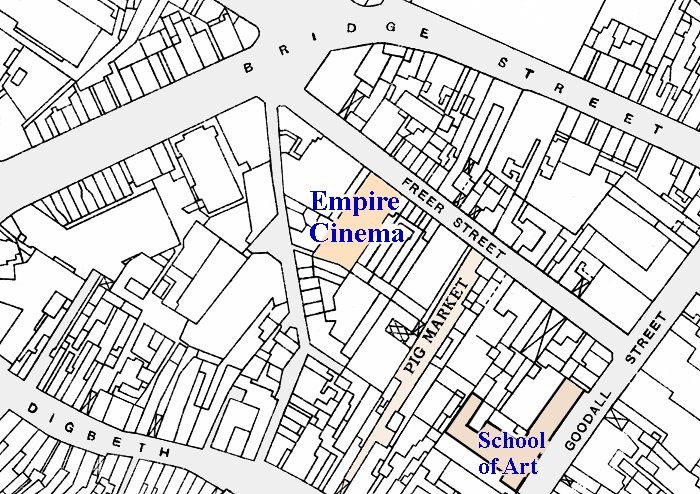

The Gaumont Cinema in

Bridge Street, where Coffee Republic and the

Co-op supermarket are today. |

A 1922 view of Bridge Street and the

Gaumont. From an old postcard.

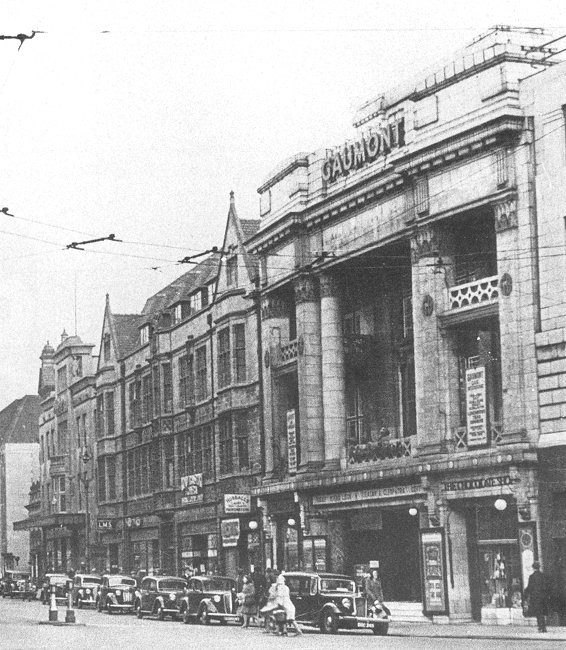

The Palace Cinema in the Old Square.

An advert from 1921.

A view of the Palace Cinema from 1949.

Shortages

F. W. Willmore includes an interesting

letter in his History of Walsall which gives an insight into

some of the problems faced by local people in the early

years of the century. It is from the December 1804 edition

of The Gentleman’s Magazine, and describes the inconvenience

caused by a shortage of small coins:

| Much inconvenience is felt in this

neighbourhood for want of silver in change.

There are many collieries, lime works,

forges, and furnaces which employ hundreds

of people, and the masters to pay their

workmen issue cards of various sorts, from

one shilling to ten each, nominal value.

These cards have been brought to the market

town adjacent, and paid for provisions,

clothing and other things, so that they

became a drug, and very little hard cash is

to be seen. Moreover, many of these have

been counterfeited, and the holders have

been obliged to sustain the loss. |

|

Water Supply

In 1804 large scale repairs to the

town’s water pipes were necessary in order to ensure that

the supply was clean and pure. In 1806 the network was

extended, and in 1810 and 1813 improvements were made to the

drainage system in High Street and Rushall Street. In 1814

the whole system was renovated at the cost of £90.

|

A final view of Her Majesty’s Theatre. From an

old postcard.

|

Law and Order

Policing in Walsall had never been

adequate, and so in 1811 after a spate of burglaries it was

decided to establish a public patrol for the protection of

common property. The parish was divided into six districts,

each with its own watch-house, which was funded from the

poor rate. Each burgess had to take a turn in keeping watch,

or find a substitute.

Each evening the people on watch would

assemble at the guildhall at 10.30 before going on duty.

They had the power to arrest and detain anyone acting

suspiciously, until the following morning, when they would

be escorted to the sheriff. If a prisoner escaped, a hue and

cry would be made in the area until he or she could be

recaptured. If a man on watch was killed in the execution of

his duty, his executors were entitled to a reward of £40. In October 1812 sixteen deputy

constables were appointed for the Borough, and eighteen for

the Foreign.

There had been a jail in Walsall since

the end of the 15th century, and a pillory, stocks and

whipping post beside the old market cross in High Street. In

the 17th century there was a town cage, and from 1627 a gaol

in the town hall. In the early 19th century it consisted of

two totally inadequate cold and damp rooms. Willmore

includes the following description in his History of

Walsall:

| Another insight into local life is

gained from some remarks on Walsall Gaol, by

a Mr. Nields to

Dr. Lettsom in 1802. He says, “Town Gaol, William Mason

gaoler, salary none, fees ¾ and 2d. to the

Town Clerk on commitment of every felon. Two

rooms under the Town Hall, that for debtors

has a fireplace, it is down five steps with

an iron grated window to the street, but not

being glazed and no inside shutters is

extremely cold, straw only upon the damp

brick floor to sleep upon. A door opens out

of this room into a dark dungeon for felons,

about three yards square. Adjoining to the

debtors room is one for felons, with an iron

grated window to the street, and two dark

dungeons with straw on the floor to sleep

on. Allowance to debtors and felons 2d. per

day. No court, no sewer, no water. The

beadle told me he brought it to the grating

for the prisoners. Felons for petty offences

remain here till the Quarter Sessions. The

debtors are confined here for less than 10s. |

|

Things improved somewhat in 1815 when

the gaol was rebuilt in the basement of the guildhall. It

then consisted of six damp cells around a small yard. There

were three fireplaces, but the walls were frequently so damp

that moisture trickled down them. The prisoner’s allowance

was limited to bread and water. At the same time a house was

built for the gaoler, who by 1833 received a proper salary.

Under the terms of the 1824 Improvement

Act, many improvements were made in the town, including the

provision of a night watch. In 1825 and 1826 watch men were

appointed, but the service was soon discontinued because of

inadequate funds.

|

|

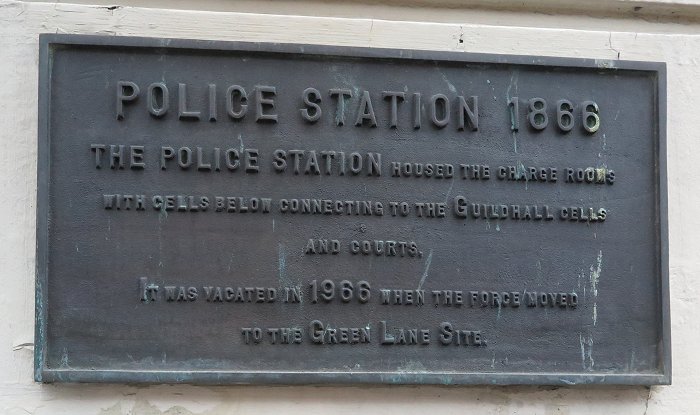

The plaque on the old police station in Goodall Street. |

|

The old police station in Goodall Street. |

Things came to a head in the early

1830s. During the miners’ strike in 1831 six hundred special

constables were enrolled, and on election day in 1832 more

were enrolled, and troops were brought-in. At this time a

permanent police force was established, consisting of a

superintendent, and three officers.

They were based at a

police station that was next to the churchyard, and also

housed the fire engine. The building, known as the Station

House, was for the use of the police and the temporary

confinement of prisoners awaiting their appearance before

the magistrates. The cells were small, and the admission of

light and air was precluded by a mound of earth in the

churchyard, which surrounded the back of the building.

There

were no fireplaces in the cells, and the prisoners only had

straw to lie on. They had no blankets and were sometimes

kept there for eight days. Sometimes police officers would

allow them to use their front room where there was a fire.

In 1836 extra police officers were

appointed for Sunday duties, and in 1843 a new police

station was built in Goodall Street. From 1837, following an agreement with the County

Magistrates, prisoners from Walsall were housed in Stafford

Jail, and in 1843 Walsall Gaol was replaced by a lock-up in Goodall Street police station.

|

|

The Walsall police force came

into existence on the 6th July, 1832 after the Town

Clerk had written to the Commissioner of the

Metropolitan Police Force asking him to recommend a

man to form a police force in Walsall. The man

chosen was Mr. F. H. West who became Walsall's first

Police Superintendent. The following is from the

first report of the Commissioners on the Municipal

Corporations of England and Wales, March 1835:

|

The

Police consists of a

superintendent and three

permanent police officers,

appointed by the magistrates

during pleasure, and the two

sergeants-at-mace, in

addition to two constables

appointed at the court leet,

and 16 deputy constables for

the borough and 20 for the

foreign.

The

Superintendent and the three

police officers were first

appointed in July 1832. The

Superintendent receives a

salary of £70 a year, the

three officers, l7 shillings

a week each. The expense of

the establishment is

defrayed by a voluntary

subscription, to which the

corporation contribute

annually £50. In general all

warrants are executed by

these officers; before their

appointment they were

usually executed by the

sergeants-at-mace.

There

is no nightly watch. The

town is lighted and paved

under the direction of

commissioners appointed

under a local Act of George

IV. The commissioners are

authorised by the Act to

appoint nightly watchmen,

and in 1825 and 1826

watchmen were accordingly

appointed. They were however

shortly afterwards

discontinued, in consequence

of the rate which the

commissioners were empowered

to levy proving inadequate

to the purposes of the Act.

Upon

these watchmen being

discontinued, the

inhabitants of the principal

street in the town

contributed by subscription

to maintain a watch; but

this also was shortly after

abandoned, and the town has

not been watched by night

for several years. It was

stated that a nightly watch

was much required, though

the establishment of the new

police in some measure

lessens the evil which might

otherwise result from the

want of it.

Gaol

The

borough Gaol is situated

under the town hall, below

the level of the street. It

consists of six cells,

inclosing a small yard of

very insufficient

dimensions. This

establishment is altogether

of an unsatisfactory

character: no classification

beyond the separation of men

from women can be effected;

neither is it possible to

separate prisoners committed

for trial from those under

sentence after conviction.

There

is not sufficient space for

air or necessary exercise.

There are three fire places

in the gaol, but the cells

are frequently very damp; so

much so, that the moisture

trickles down the walls. The

prison allowance is limited

to bread and water. The

magistrates do not visit the

gaol regularly; sometimes an

interval of six months or

even more is suffered to

elapse without any

visitation being made. It

was stated by the gaoler,

that he had never known the

magistrate to visit the gaol

during the winter months.

The

mayor has the custody of the

gaol. He appoints a deputy

gaoler, usually one of the

sergeants-at-mace, who

receives as such, a salary

of £12.l0s. a year.

Station House

For the

use of the police and the

temporary confinement of

persons apprehended by them,

a station house has been

fitted up by the

corporation. It consists of

an entrance room for the use

of the officers, and two

cells for the confinement of

prisoners. This building is

also of a very inferior

description. The cells are

small, and the admission of

light and air to them is

precluded by a mound of

earth forming part of the

churchyard, which surrounds

the back of the building,

and rises nearly to the

height of the roof. The

walls are damp, and the

cells are without fire

places; the prisoners have

only straw to lie on, and

are not furnished with

blankets. Persons are seldom

confined here more than a

night, but it sometimes

happens that they are

detained longer: prisoners

have been kept here for

eight days, and in one

instance a female was

detained for a fortnight.

The officers usually allow

persons in custody to remain

in the front room, in which

they themselves sit, and in

which there is a fire; but

this is an indulgence

depending entirely on their

pleasure, and is not always

accorded. |

|

|

|

As already mentioned, the town’s fire

engine was housed in the police station next to the

churchyard. There had been a fire engine at Walsall since

the late 18th century.

It had been kept in the west porch of

St. Matthew’s Church, and also in an engine house near the lich gate, which had been built around 1790. The Improvement

Act of 1824 gave the town commissioners the authority to

provide a fire engine, which was kept in the engine house

next to the churchyard.

By the early 1840s there were two

new fire engines in the town, one in Lichfield Street

belonging to the Norwich Union Fire Office, and another in

Bridge Street belonging to the Birmingham Fire Office. When

they arrived, the parish fire engine was sold, and in the

early 1850s the old engine house was demolished.

|

Another view of the old police station in Goodall Street. |

| The Corporation fire brigade was formed

in 1879 and based at the police station in Goodall Street.

There were also sub-stations at Stafford Street police

station and Bloxwich police station. The brigade came under

the control of the chief constable in 1888. |

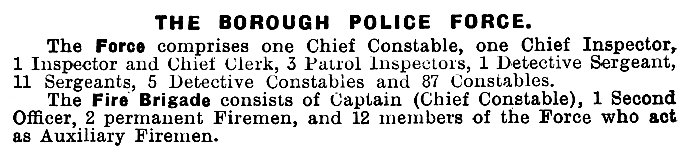

From the 1934 Walsall Red Book.

From the 1899 Walsall Red Book.

|

A new Grandstand

In 1809 a grandstand was added to

Walsall’s racecourse, which opened on Long Meadow in 1777.

The grand stand, which was supported by annual

subscriptions, was built at a cost of £1,300, and by 1823

had 34 subscribers, each of whom possessed a "subscribers'

ticket," entitling them to free admission.

It contained a

billiard room on the ground floor, and had a turret with a

bell. It survived until 1879 when it was sold for £72, and

removed from the site.

The races, which attracted large

numbers of visitors to the town, were supported by the

Corporation, which paid five pounds annually towards the

running of the course.

After each meeting a ball was held at

the George Hotel. In 1828 the Gold Cup was won by "Maria

Darlington," a chestnut mare belonging to Mr. Fletcher.

The

event was celebrated by Miss Foote, a popular actress, and

the Countess of Harrington who later that day sang "Little

Jockey" at the Walsall Theatre. |

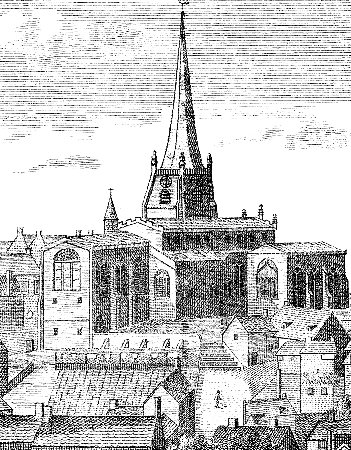

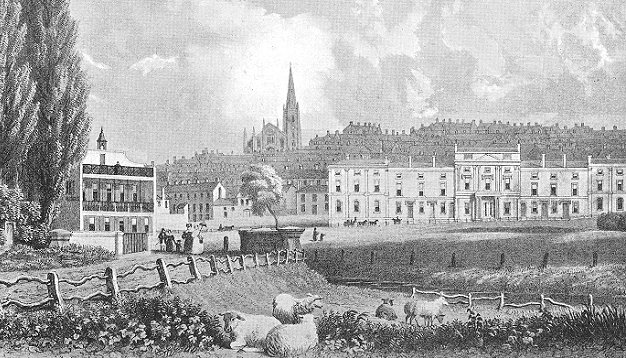

| Looking across the

town towards the parish church in 1795. From F.

W. Willmore's History of Walsall. |

|

The old racecourse. From the 1899 Walsall Red

Book.

|

The Market

During the Napoleonic Wars the market

thrived, selling large quantities of Irish bacon to the

navy. Live pigs were shipped from Ireland for the purpose.

When the war ended in 1815 Walsall market continued to trade

in Irish pigs, and was one of the main English markets

dealing in them. Shopkeepers in High Street used to let pig

pens in front of their shops for the accommodation of the

pigs. In 1815 when a proper pig market was provided at the

back of High Street there was considerable opposition.

It has been claimed that in 1855 as

many as 2,000 pigs were brought to the market in a day. The

trade at Walsall soon suffered because of the coming of the

railways, and by 1889 few pigs were sold. During the latter

part of the century the market concentrated on general

retail sales, and grain. In 1835 barley, beans, oats, peas,

and wheat, were for sale.

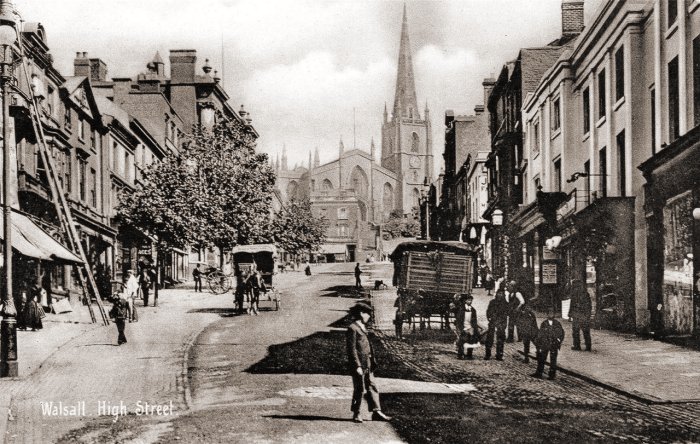

High Street in 1861. From an old

postcard.

The Gas Works

In the early 1820s there was great

dissatisfaction with the state of the town, particularly

with the lack of street lighting. On 28th May, 1824 the

Corporation obtained an improvement act for the town, at a

cost of £620. The 1824 Improvement Act gave the Corporation

powers to carry out improvements in the town centre,

including paving, lighting, and widening the roads. The

improvements were supervised by the improvement

commissioners, a body which included the mayor, capital

burgesses, the recorder, the town clerk, the vicar of St.

Matthew’s, the headmaster of the grammar school, the steward

of the manor of Walsall, the churchwardens, the overseers of

the poor, and 46 others.

The area for improvement covered the

Borough, Stafford Street, Wolverhampton Road, Marsh Lane,

Birmingham Street, part of King Street, and part of New

Street.

The commissioners had the power to make

and repair pavements, order residents to connect their

property to a sewer on pain of a £10 fine, light the streets

with gas and oil lamps, build a gas works, appoint and pay

watchmen, cleanse, name, and number the streets, ensure that

steam engines would consume their own smoke, on penalty of a

40 shillings per day fine to the owner, and provide a fire

engine, and weighing machine.

It was to be paid for by a rate not

exceeding three shillings, but in reality this was

insufficient. The improvements were subsidised by an

additional £900 from the Corporation.

In 1826 they opened a gas works on the

site of Arboretum Road. It was designed in 1825 by the

famous engineer John Urpeth Rastrick who formed Foster,

Rastrick and Company at Stourbridge with James Foster, and

built some early locomotives including the Stourbridge Lion.

The gas works were erected at a cost of £4,000, and let at

such a high rent that the Walsall rates were much lower than

in neighbouring towns. Unfortunately the gas works could not

keep up with the growing demand, and so in 1850 a new gas

works was built in Wolverhampton Street, alongside the

canal.

The work of the improvement

commissioners was taken over by the Corporation in 1876, and

in 1877 Pleck Gas Works was built by the canal.

Wolverhampton Street gas works then became a storage

facility.

The extensions to Walsall Gas Works.

From the 1937 Walsall Red Book.

Developments on The Bridge

At the start of the century the section

of Walsall Brook crossing The Bridge was fully exposed,

shallow, wide, and prone to flooding. It almost divided the

town in two, with Park Street and Digbeth sloping down to

the level of the stream. The houses on either side were

approached by flights of steps, so the whole area looked

very different to what we see today. The brook was crossed

by a low footbridge, which in times of flood could be

partially underwater. When this occurred ladies were carried

across on horseback for a fare of one penny. Horses were

kept for this purpose at the New Inn.

Around 1813 work began on improving the

area starting with the removal of the old manorial mill

which for some time had been used as a blacksmith’s shop by

a Mr. Chadwick. It was soon demolished and the materials

were sold for £31. In front of it was a watering place for

horses, and alongside stood a rubbish heap. Between the New

Inn at the bottom of Park Street and the brook, was a large

well known cock pit which was very popular during race

meetings.

Initially the mill race was partly

covered over, and remained as such until the enlarging of

the square to its present size in 1851. Other changes on The

Bridge included the enlarging of the Blue Coat School in

1826, and the enlarging of the George Hotel, also in 1826.

The pillars that adorned the front of the hotel were

purchased from the Marquis of Donegal in 1822. They formerly

stood in front of his stately home, Fisherwick Hall, which

was demolished. Before the work on the hotel began, the

front entrance was in Digbeth.

|

The Bridge and the enlarged George Hotel. From

an old postcard.

|

The Corn Laws, Politics,

and Rioting

The Corn Laws were introduced in 1815

to protect British farmers from cheap imported grain. No

foreign grain could be imported until domestic grain had

reached 80 shillings per quarter. It was seen as a way of

stabilising wheat prices, but in reality caused violent

fluctuations in food prices, and led to the hoarding of

grain. This only benefited landowners. At the time all MPs

had to be landowners.

It caused great hardship and distress

amongst the working classes, who could not grow their own

corn, and had to spend most of their earnings on over-priced

food in order to stay alive. There was much opposition to

the laws, which were not repealed until 1846. The following

extract from the edition of the Wolverhampton Chronicle

published on 6th November, 1815 describes some of the local

opposition to the inflated prices:

| The town of Walsall was thrown into

confusion on Tuesday night by a numerous

assembly of persons, by whom the windows of

several bakers were broken, and who

eventually attacked the new mill near that

place. They did not succeed in getting into

the mill, but they either destroyed or

carried away everything they could find in

the adjoining dwelling house. |

|

By 1820 Walsall was in the grip of a

severe depression, which caused much anger, and the signing

of the following petition:

| To Charles Windle, Esq., Mayor of the

Borough and Foreign of Walsall. Sir, we the

undersigned, do hereby request you to call a

meeting as soon as possible of the

merchants, factors, manufacturers, and other

inhabitants of the Borough and Foreign of

Walsall, to take into consideration the very

depressed and impoverished state of the said

parishes, and to draw up a petition to the

Commons House of Parliament thereupon, and

to adopt such measures as may be proper,

right, and legal. |

|

The petition, which had been signed by

a number of prominent citizens, led to a meeting at the

Guildhall, and the sending of a petition from Walsall to

Parliament which included details of the immense burden of

the poor rate, and implored Parliament not to accede to any

proposals for enhancing the price of agricultural produce.

Leicester Square in the early 1900s.

From an old postcard.

Due to the high taxes, and high food

prices, the inhabitants of Walsall took an active part in

calling for the reform of parliament. Many joined the

Birmingham Political Union and held numerous meetings in the

town. In 1830 the Political Union for Walsall was formed at

a meeting in the Black Boy Inn in Fieldgate. Prominent

members included Samuel Cox, B. Abnett, J. Cotterell,

William Cotterell, and Joseph Hicken who was appointed

secretary. He later became secretary to the Anti-Corn Law

League founded in 1838.

In 1830 the anti-reform Tory Government

led by the Duke of Wellington were defeated, bringing Earl

Grey and the Whigs to power. A Reform Bill was introduced

March 1831, but it failed to get through Parliament and Grey

resigned, which led to a general election. It was fought on

the question of reform, and resulted in the re-election of

Grey and the Whigs with an increased majority. A second

Reform Bill was introduced, which went through the Commons,

and was awaiting its passage through the House of Lords.

Fearing that it would not be passed by the House of Lords,

the Birmingham Political Union held a meeting at Newhall

Hill, Birmingham to pressurise the Lords into accepting the

Bill. Around 15,000 people attended the meeting, but the

Bill was rejected, and large scale riots were held

throughout the country.

The Bill again passed through

Parliament with a large majority in March 1832, but it was

again feared that it would be rejected by the House of

Lords. By now the Political Union for Walsall had greatly

increased in size, and meetings were held at the Duke of

Wellington in Stafford Street, which was renamed the Earl

Grey. Because of the fear that the Bill would not be passed

by the House of Lords, around 200,000 people gathered at

Newhall Hill, Birmingham in what was known as the Meeting of

the Unions. Their aim was to pressurise the House of Lords

into accepting the Bill.

Around 500 members of the Walsall Union

met at five o’clock on the morning of May 17th at the back

of Mr. Hicken’s house in Windmill Street and with a brass

band playing, marched to Handsworth. They were met by

members of the Wolverhampton Union, and after a lively

discussion, Walsall took the lead into Birmingham. In spite

of the massive show of support for the Bill, it was defeated

in the Lords, and Grey resigned. The King called upon the

Duke of Wellington to form a new government, but he was

unable to do so, and Grey was recalled to office.

Feelings in Walsall were high, as can

be seen from the following article that appeared in the May

23rd edition of the Wolverhampton Chronicle:

| On Friday evening last, an effigy

intended to represent a noble duke, was

carried through the streets of Walsall. In

Stafford Street a man named Spencer,

probably to show his detestation of the

original, fired at the figure, as others had

done in its progress, but his pistol being

foul, instead of injuring the head of his

supposed enemy, rebounded against his own,

which was severely lacerated, etc. Mr.

Spencer is likely to carry with him for the

future a mark of his zeal in the cause of

reform. |

|

On 4th June the Bill finally passed

through the House of Lords and received its Royal assent

three days later. It was greatly welcomed and celebrated

throughout the country. Feelings were so high, that if the

Bill had not been passed, a revolution could easily have

followed.

As a result of the Reform Act of 1832

Walsall became a Parliamentary Borough. In December of that

year Charles Smith Forster, a Tory, a local banker and

former mayor was elected as Walsall’s first Member of the

reformed parliament., a seat he held until 1837. There was

much excitement in the town during the election, mainly as a

result of the political unions. Over ten thousand people

marched through High Street to the Dragon Inn where the

flags and banners were deposited. Many were members of the

Birmingham Political Council who supported Thomas Attwood,

one of the candidates, and one of their founders. A battle

followed between the Birmingham and Walsall men who were

armed with sticks and other weapons.

When Mr Attwood’s followers were

expelled from the George Hotel, the Birmingham mob broke

every window and forced entry into the hotel removing any

piece of furniture they could find, which was piled on The

Bridge, and set alight.

The Riot Act was read, and two

companies of the 33rd Foot charged the protestors with fixed

bayonets, until law and order was obtained. On the election

the following day, a company of the 33rd Regiment, and a

detachment of the Scots Greys was on hand in case of

trouble. An immense crowd formed on The Bridge, and a large

bonfire was lit. Attwood’s supporters tried to prevent

Forster’s supporters from reaching the polling booth. The

riot Act was again read, but the special constables that

were on duty could not control the angry crowd, and so the

Scots Greys charged through the mob on horseback, soon

putting them to flight. During the scuffle thirty five

arrests were made. It was a sad episode in Walsall’s

political life.

Other happenings in the 1820s and 30s

In May 1824 Walsall’s first savings

bank opened on The Bridge under the patronage of the Earl of

Bradford, the Earl of Dartmouth and others. Within a year

deposits amounted to over £7,000.

In the edition of the Wolverhampton

Chronicle for 23rd January, 1820 there is a mention of body

snatching in Walsall. At the time, the so called

‘Resurrectionists’ would open graves and remove, and sell

corpses for dissection or anatomy lectures in medical

schools. The news item is as follows:

|

Ressurrectionists

Several of these gentry have been

lately prowling about the neighbourhood of Lichfield, and

last week they stole the body of an elderly female from

Walsall Burial Ground.

|

|

In 1825 the Corporation finally decided

to discontinue the Mollesley Dole. In its place the

Corporation built eleven almshouses by St. Mathew’s burial

ground, for poor women, five from the Borough, five from the

Foreign, and one from Rushall. The decision was unpopular

and resulted in a considerable disturbance in the town.

Placards were put-up, and the authorities were subjected to

a great deal of scurrilous abuse.

The 2nd May, 1831 saw the opening of

Bradford Street, a new road to greatly improve the journey

between Walsall and Darlaston, and Wednesbury. People

assembled on the opening day to watch Mr. Quinton’s

Birmingham coach pass along the road, and stop half way for

the road naming ceremony.

The Coronation of William IV took place

on Tuesday 8th September, 1831. This was celebrated in

Walsall by a procession through the town which marched to

the grandstand at the racecourse. It consisted of the

mayor, John Heeley, the corporation, the odd fellows, the

druids, and other lodges. A few days later school children

paraded through the town to the racecourse where they were

given wine and cake. |

| In 1832 the town received an unwelcome visitor in the

form of Asiatic Cholera, which had been sweeping through

much of the country. In June it appeared at Tipton, and in

August caused a large number of deaths in Bilston.

It was suggested at the time that it arrived in Walsall

direct from Bilston, carried by the water in the canal,

mainly because the first victims lived alongside the canal.

|

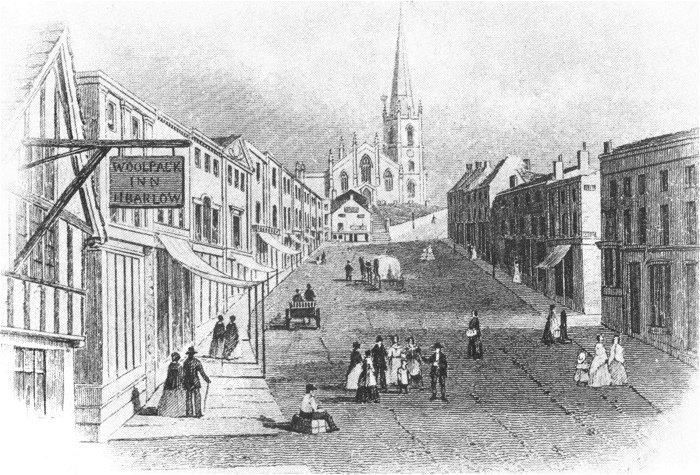

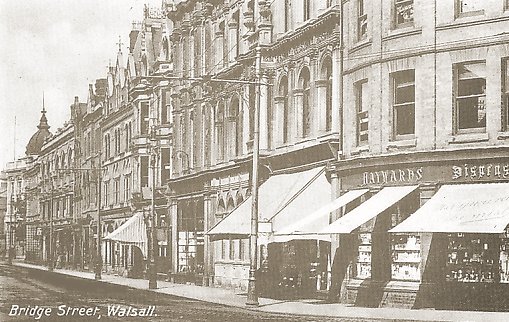

Bridge Street, originally called New

Street. From an old postcard. |

| The first man in Walsall to die from the disease lodged

in a house on the bank of the canal, and died within 24

hours. Another man who worked on one of the boats met with

the same fate. The whole neighbourhood around Walsall Town

Wharf was affected. People were dying rapidly, and no one

could be found to put them into coffins and carry them away

for burial. The local authority had to employ a man to go

around the neighbourhood twice daily, to remove the corpses.

One resident, Thomas Jackson, described the disease as a

shocking and agonising pain in the stomach and the bowels,

and cramp in the limbs, where life, even in the strongest

man, seldom held out for more than thirty hours. In that

year there were 346 cases of the disease in the town, and 85

deaths.

| |

|

Read a contemporary

description of

the cholera epidemic |

|

| |

|

The Walsall Horticultural Society was

formed in 1834 thanks to the efforts of Dr. Kent and Mr. C.

F. Darwall. It prospered for three years, but soon came to

an end. The society reformed in 1880.

A New Council

When Lord Grey’s government had

succeeded in reforming parliament its attention turned to

local government. In February 1833 a select committee was

appointed to look into the state of Municipal Corporations

in England, Wales, and Ireland, and to report any abuses

that existed in them, and what corrective measures were

needed.

The commission issued its report in

1835 after investigating 285 towns, including Walsall. The

findings of the report led to passing of the Municipal

Corporations Act of 1835. The Act established a uniform

system of municipal boroughs, each governed by a town

council that was annually elected by ratepayers. The council

in turn were to elect aldermen to serve on it, with a six

year term. Towns were divided into wards. The Act reformed

178 Boroughs, and others soon followed.

The publication of the commission’s

report led to a crisis in Walsall. The Mayor, Charles

Forster Cotterell resigned, but was then informed by the

steward of the lord of the manor, that he could not resign.

This led to a special meeting of the Corporation who took

legal advice on how to proceed. A writ was issued by the

King’s Bench, ordering the Mayor to return to his office,

but he failed to do so.

A petition was sent to the House of

Commons from the inhabitants of Walsall in favour of reform,

and under the terms of the Municipal Corporations Act the

old Corporation was restructured into the new Borough

Council.

The first council elections were held

in December 1835, with only one member of the old

Corporation elected, he was Charles Forster Cotterell who

was re-elected as Mayor. The first council members were as

follows:

Foreign Ward: Charles Forster Cotterill,

Henry Wilkinson Wennington, Edwards Elijah Stanley, David

Badger, John Brewer, and Moore Hildick.

St. George’s Ward: Richard James

junior, Joseph Cowley, Samuel Powell, John Eglington, John

Wilkes, and Thomas Hackett.

Bridge Ward: Charles Forster Cotterill,

Joseph Cotterill, William Dixon, Samuel Smith, Thomas

Dutton, and Charles Mason.

The new council met for the first time

in January 1836.

|

|

The Bridge.

From an old postcard. |

|

Walsall in 1835

In the early part of the century, the

old Corporation did little for the town directly, but was

active through the improvement commissioners, who did their

best to improve the town, according to the limited means at

their disposal. The principal improvements included the

construction of Lichfield Street, a fine new street

connecting Bridge Street to Lichfield Road. Other new

streets included Bradford Street, Goodall Street, Freer

Street, Mountrath Street, Great Newport Street, and Little

Newport Street. Many old buildings were removed or rebuilt,

and the growing, prosperous town began to look more

affluent.

| |

|

Read about the

Walsall Red

Books and the Walsall

Advertiser |

|

| |

|

Although there had been many problems

with law and order, particularly due to people’s anger over

the Corn Laws and the Reform Bill, the same problems were

almost universal at the time.

The population was still growing, and

more manufacturing industries were appearing, which would

guarantee the future prosperity of the town. Walsall could

look forward to bright future.

|

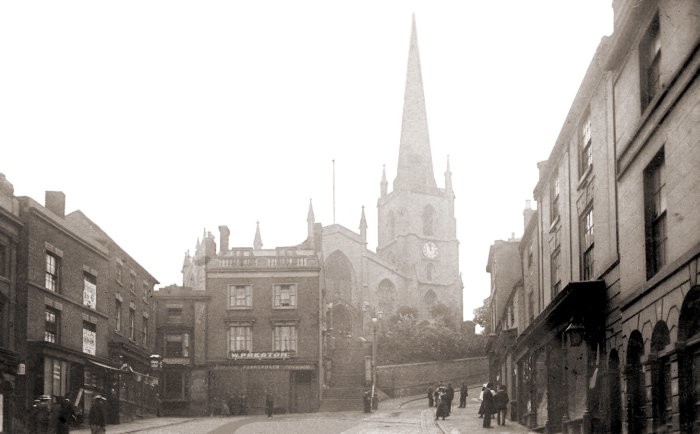

The view from the top of High

Street looking into Upper Rushall Street, around the end

of the 19th century. The shop by the church steps was

owned by William Preston, a pawnbroker. From an old

postcard. |

|

A similar view from lower down

High Street. From an old postcard. |

|

From an old postcard. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to Religion |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to Industry |

|