|

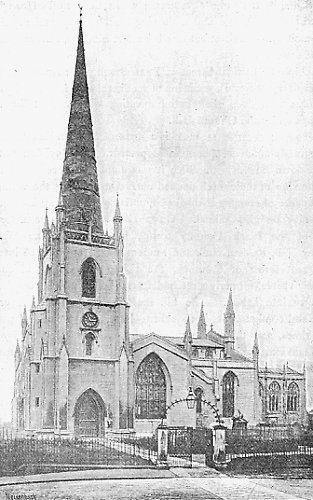

St. Matthew’s Church has dominated the

Walsall skyline since the 13th century. The inner crypt,

which dates from that time, is the oldest man-made structure

in the town. It is possible that its Norman doorway could

date from the previous century.

The church was originally dedicated to

All Saints, and remained as such until the 18th

century when it was rededicated to Saint Matthew.

The building consists of a chancel, a

nave with aisles, transepts, an organ chamber, and a tower

with a spire, containing a clock and twelve bells.

The earliest surviving reference to the

church, dating from around 1220 is a grant by William Ruffus

to the Abbey of St. Mary in Halesowen, for the patronage of

the church. The grant was confirmed by Henry III in 1258.

|

From an old postcard. |

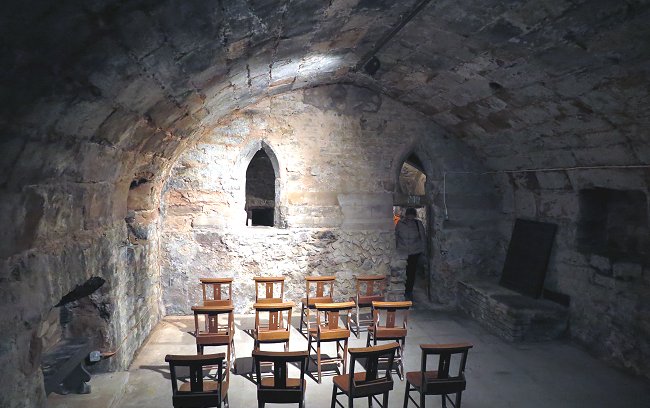

The northern end of the inner

crypt with its original cupboard (minus doors) on the

right. The cupboard was possible an aumbry used to store

holy vessels. |

The southern end of the inner crypt, the

oldest man-made structure in Walsall.

|

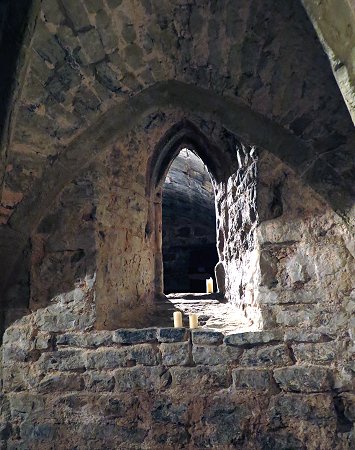

The original window, possibly

Norman, which once looked across to where Ablewell

Street and the Chuckery now stand.

Beyond is the later outer crypt. |

The outer crypt looking towards the inner

crypt, with its original Norman window, and doorway.

| Frederic Willmore in his 'History of

Walsall and its Neighbourhood' suggests that the church was

replaced by a much larger building in the 14th century: |

|

In the latter half of the 14th

century, there appears strong circumstantial evidence that a

much larger building of transition Gothic style was erected,

and the main reasons for this theory are as follows:-

1. The lords of the manor at

that time were Ralph, last Lord Bassett, and Thomas

Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who died in 1401, both wealthy

and powerful men. This Earl of Warwick is known to have

enlarged and rebuilt during his retirement many of the

churches on his various estates, and that he took a direct

interest in the church here is shown by the fact that two of

the windows bore his arms, and that they were also carved on

the stone pulpit and on the existing font. The church

contained also two monuments of the Hillarys, both of whom

died before 1400, while other coats of arms of Ferrers, of

Groby, and the Stafford family, relate to the same time.

2. The general architecture of

the church as evidenced by the discovery of an ancient

window and other medieval remains at the time of the

restoration in 1879, points to the same date, whilst the

enlargement of the building is proved by the fact that the

chancel was carried by means of the present massive archway

over a public road, which then crossed the church yard. |

|

The Hillary Effigy.

|

In the middle ages the church had a number of chantries,

for the exclusive benefit of local wealthy land-owning

families who gave money, and endowed land to the chantries,

which were there to ease their souls into the after life by

the process of prayer. Daily services and prayers were

carried out by the chantry priest, who was funded by the

endowment, usually the income from the endowed land. The

original chantries were those of Saint John the Baptist, The

Blessed Mary, Saint Clement, Saint Catherine, and Saint

Nicholas.

Others were founded by Sir John Hillary,

Sir Roger Hillary, Sir Thomas Aston, John de Beverleye,

William Colesone, Sir Thomas Aston, and Thomas Mollesley,

who is remembered for his Mollesley dole. In the Valor

Ecclesiasticus of 1535 Walsall is described as a vicarage

with ten chantries.

The chantries continued in use until

Henry VIII’s reformation. They were abolished by an Act of

Parliament in 1547, which would have greatly reduced the

church’s income. The chantry priests were pensioned-off, and

much of the chantry land was kept by the crown, or sold for

the benefit of the crown. The remaining land came under the

control of the Lord of the Manor, John Dudley. |

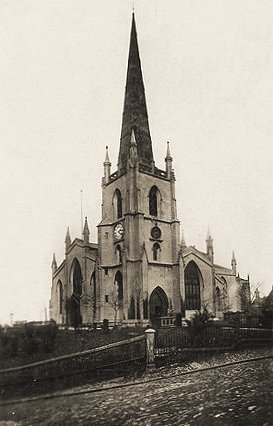

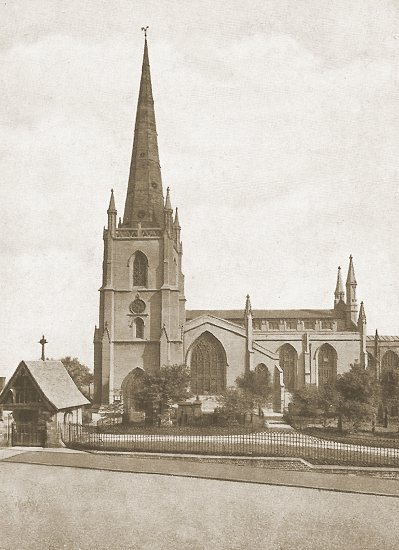

From an old postcard. |

|

The maker's nameplate on the church

clock. |

The church had at least five alters,

and contained two chapels, one dedicated to Saint

Clement (in the north transept), and another dedicated to

Saint Catherine (in the south transept). For several hundred

years the vicars at the church were appointed from the

priests at Halesowen Abbey. |

From an old postcard.

|

Parts of the church, including the

chancel, were rebuilt and redecorated in the late 15th

century. The work included lengthening the chancel,

extending the nave, and moving the rood screen. Around the

same time, the tower which includes the porch was built,

possibly with the first stone spire.

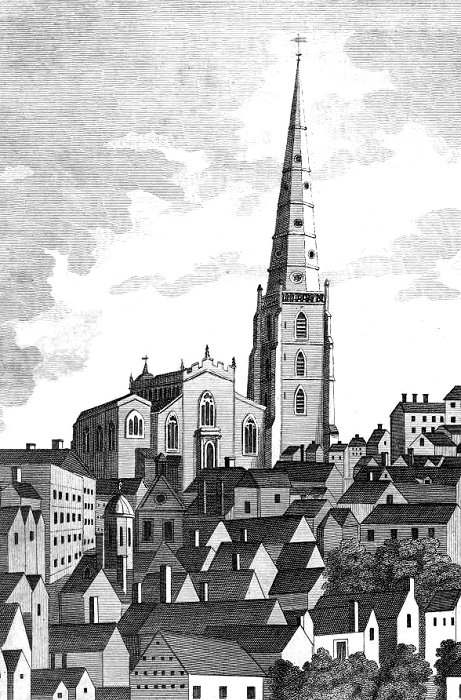

In 1669 the spire was rebuilt, and in

1777 completely replaced, when the tower was reduced in

height. The contractor was John Cheshire.

By 1466 there was a chiming clock in

the tower which was repaired in the 17th century by the

corporation. At the time there were sun dials on the tower,

which were replaced by a clock with dials in the 1790s. An illuminated clock

made by J. Smith & Sons, of Clerkenwell, London was

installed in 1865. It has three dials, eight feet in diameter,

each glazed

with opal glass. |

The church clock. |

The previous, taller tower.

|

From the 1889 Guide to Walsall. |

The tower has contained a peal of bells

since the 16th century. In 1553 there were four bells, by

1656 there were five, and in 1674 there were six.

In 1731 the ‘great bell’ was recast by

Joseph Smith of Edgbaston, and in 1775 several were recast

by Thomas Rudhall of Gloucester. By this time there were

eight bells. Two bells were added in1863, and two more in

1928 to 1929 when the other ten bells were recast by Taylor &

Company of Loughborough.

The earliest reference to an organ is

in a document from 1473. Tradition has it that the finely

carved bench ends, armrests, and misericords are from

Halesowen Abbey, but no evidence for this exists. They were

possibly carved during the 15th century redecoration, which

included new stalls.

Although the Reformation greatly reduced the church’s

income, it received many gifts, and charities were set up

for the priests. Around 1618 William Wheate of Coventry

acquired land, to be rented. The rent paid for four annual

sermons in the church. In the 1620s John Parker gave eight

pound annually to pay for sixteen sermons, four in Walsall

parish church, four at Rushall, and eight at Bloxwich. He

also gave 40 shillings a year for the upkeep of Bloxwich

Chapel and chapel yard. |

|

Some of the well-preserved 15th

century carvings in the chancel, which represent medieval

wood carving at its best. |

|

Other benefactors who gave money for

the upkeep of Walsall church included Robert Parker,

Nicholas Parker, Sir William Craven, and Henry Stone.

Walsall church suffered greatly during

the Civil War. The organ was pulled down and burnt, along

with prayer books. Monuments, carvings and windows were

destroyed or mutilated when the building was used as a

stable.

In 1697 a new organ was built by

Bernard Smith at the east end of the nave. It survived until

1773 when it was replaced by a new organ built by Samuel

Green of London, and later greatly modified, initially being

enlarged in 1844, and then totally remodelled in 1880.

|

The 15th century octagonal font which

has an 18th century alabaster rim. |

The nave looking towards the chancel.

The nave looking westwards.

The late 15th century chancel, restored in

1879-80 by Ewan Christian of London.

|

During the late 18th century some

essential repairs were carried out, and several private

galleries were erected. F. W. Willmore in his History of

Walsall refers to the following sections from an old

manuscript, which describes the building work as follows:

In the year 1785, the new

improvements to a place called the Ditch were made, and a

new roof was made and completed on the south side of Walsall

Church; in doing of which William Sirdefield the undertaker

of the carpenters’ work, lost his life by a wheel going over

his leg, which mortified. In 1787, a new roof over the vestry

and part of the north roof was made and completed at the

expense of Walsall Parish, and in 1790, the steps and

passages leading to the church were in part paved with

stone.

In 1802, a new wall and additional

steps were built and completed in churchyards leading into

the Ditch, and a new roof was made over Nock’s gallery on

the north side of the church.

Willmore also includes part of a letter that was

published in the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1798. It was

written by a local historian named Gee, who was described by

Stebbing Shaw as a self-taught genius. The letter describes

the church at the time:

This church stands on a lofty hill consisting of an

immense body of sand and gravel, and the entrance into the

churchyard from the high street was (as it is now) by a

number of stone steps, but not so steep formerly nor having

so many steps as at present, which are 62 in number.

Over the highest flight of them

there were some ordinary old buildings, which narrowed the

passage and obstructed the view of the west front of the

church. When arrived at the landing place

there were two roads, one to the right and the other to the

left, which led in a circuitous way to the north and south

porches.

|

|

There was also an ancient enclosed

porch at the west door; but this was not much used as a

passage, but served to contain the fire engines, and after

they were removed to a building erected for the purpose near

the lich gates.

Some poor people sat in this porch

on a Sunday, whence they had a full view of the minister,

but within these few years there have been many alterations.

The old building over the uppermost flight of steps has been

taken down, and perhaps this was the only thing done right

in the business.

The old western porch, instead of

being repaired, has been with some trouble also pulled down,

and a modern open portico of the Tuscan or Doric order set

up in the place. As there is now only one door to this entrance, in

bad weather it is obliged to be kept shut, as the wind blows

that way full into the nave; and in order to make a new road

to this door the churchyard has been fairly cut in two, a

passage having been made 24 yards in length and about as

deep as a navigable canal (to which it bears some

resemblance); and the dead have been raised up. |

From an old postcard. Courtesy of

Christine and John Ashmore. |

|

The church seen from the top of High

Street. |

Corpses in all degrees of putrefaction were disturbed and

laid promiscuously in the passage leading to the north

porch, which by that means is much higher than before. The

offensive part of this business was done in the night, and

these matters were effected at an heavy expense and are no

improvements…

The floor of the east chancel is some steps higher

than that of the church, and the ground without, being many

feet lower, there is a curious passage under it, just

beneath the communion table, through a fine old Gothic arch,

for foot passengers. And under this chancel there is also a

large vault, now used to hold lumber in.

Another, a lesser

vault or crypt, opens into this, filled with the sad remains

of mortality, skulls and bones. There is a fireplace in the

large vault, and a chimney carried up within one of the

buttresses to the roof of the chancel. |

|

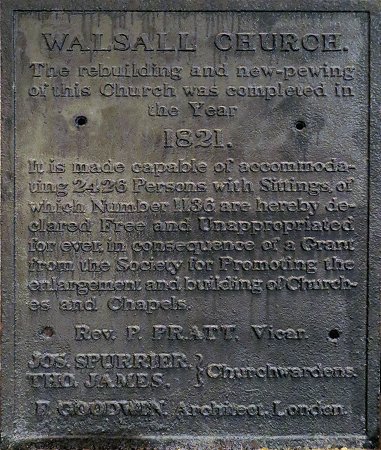

By the beginning of the 19th century

the building was in a state of disrepair, and so between1819

and 1821 much of the church was rebuilt at a cost of

£17,000.

The architect Francis Goodwin of London

added cast iron columns and window frames, and a beautiful

fan vault. The chancel gallery was removed, as were the old

pews and galleries in the nave, which were replaced with an

up-to-date design. Extra galleries were built in the side

chapels to increase the accommodation, and the old tower,

built of coarse limestone was re-cased in stone

The church was again extensively

altered in 1879 to 1880 to the design of Ewan Christian. The

chancel was partly rebuilt and opened-up with the removal of

the organ gallery, and a triple-decker pulpit that had been

built during the reconstruction of 1819 to 1821. The pews

were replaced with chairs, and the galleries over the

side-chapels, and the east gallery were removed.

The work involved the demolition of the

west portico, the addition of two new porches, and casing

the tower in Bath stone.

|

A cast-iron plaque which commemorates

the rebuilding of the church in 1821. |

| The Sister Dora memorial east window,

made by Burlison and Grylls of London, was added at a cost

of £300. |

|

The damage after the 1847 gas

explosion. From the 1899

Walsall Red Book. |

|

Part of the interior, including a

stained glass figure of Saint Matthew was badly damaged by a

gas explosion in 1847, which killed one of the beadles who

accidentally ignited the gas, and in so doing wrecked the

south-west corner inside the church.

Further building work and modifications

took place in the 20th century. New choir vestries were

completed in 1908, and around the same time the spire was

restored. Also in 1908 the organ was rebuilt, and rebuilt

again in 1953.

In 1920 Saint Clement's chapel was

refurnished as a

war memorial, and in 1927 the lich gate was built. In 1945

the patronage was transferred to the bishop of Lichfield,

and in 1951 the upper part of the spire was rebuilt.

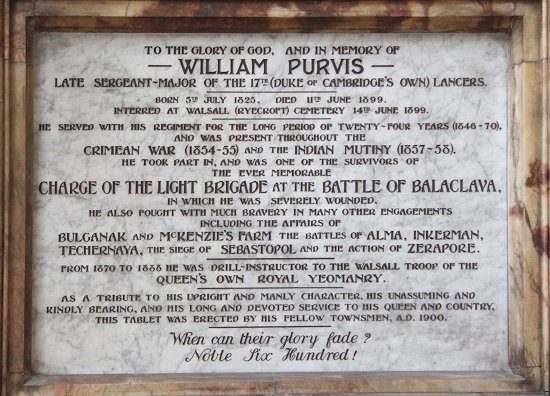

The oldest monument in the church is an

effigy of Sir Roger Hillary dating from 1399. There is also

a monument and medallion bust of William Purvis, a Walsall

soldier who served in the 17th Lancers for 24 years, and was

one of the survivors of the Charge of the Light Brigade

during the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October, 1854. In

1975 a screen and a stained-glass window were installed in

St. Catherine's chapel, which acts as the children's chapel.

St. Matthew’s Church is now Grade II*

listed. |

The lich gate, tower, and entrance. |

The memorial to William Purvis.

From an old postcard.

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|