|

Dorothy Wyndlow Pattison was born on

16th January, 1832 at the village of Hauxwell, North

Yorkshire, where her father Mark Pattison was rector of the

village church. She was the eleventh child of Jane and Mark

Pattison and lived in Hauxwell Rectory. There were ten girls

and one boy. Another boy was born later.

Sadly she had a terrible childhood,

blighted by the mental state of her depressive father, and

seemingly unloved by her mother. Shortly after her birth,

her brother Mark left home to become a student at Oxford

University. Her father greatly resented his lack of

promotion in the church, and couldn’t cope with the gap left

by his son’s departure for Oxford. In 1835 he had a mental

breakdown and was sent to an asylum in York where he was

badly treated. On his return home his illness worsened, and

his resentment turned towards his family, for sending him to

the asylum. He was sometimes violent, but Jane, his

submissive wife would always do his bidding, which included

forbidding his daughters to marry.

The girls were not allowed any formal

education beyond learning to read and write. They were left

to find their own amusements, and for a time (until

forbidden by their father) they ran the village school, and

became involved in charitable activities such as

distributing food and visiting the sick. Their elder brother

Mark, a brilliant student, became involved in the Oxford

Movement, a group of High Church Anglicans who wanted to

reinstate lost Christian traditions and include them in

Anglican liturgy and theology. They conceived the idea of

the Anglican Church being one of three branches of the

Catholic Church. Mark became Rector of Lincoln College,

Oxford.

Under Mark’s influence, his sisters

embraced the Oxford Movement, in face of their father’s

fierce opposition. Dorothy became his favourite sister, and

on several occasions accompanied him on holiday, which

allowed her to escape from the terrible conditions at home.

Unfortunately the close relationship did not survive. When

she became a nurse a few years later, he was angered because

he thought this to be an unsuitable occupation for one of

his sisters. They drifted apart, and when she died he

refused to attend her funeral.

|

|

From an old postcard. |

Whilst in her twenties Dorothy had a

couple of affairs. The first was with James Tate, the son of

the headmaster of Richmond School. The Tates were close

family friends, and James soon fell in love with the

attractive twenty year old. They intended to marry, but

James easily gave-in to her father’s refusal, which greatly

angered her.

At the same time she had a secret affair with

Purchas Stirke, a young farmer’s son who she met while fox

hunting with her sister Rachel. Purchas’s brother Robert

fell in love with Rachel, and they were married. She was

banished from her family home forever by her father.

Dorothy’s mother became fatally ill,

and Dorothy became her full-time nurse. After her mother’s

death in 1860 Dorothy decided to break-off her engagement to

James, because, as she secretly admitted to Rachel, she

preferred Purchas Stirke. This however was not to be. She

decided to end the affair with Purchas, and with the ninety pounds

left to her in her mother’s will, she decided to leave home

and start a new life elsewhere. |

|

She obtained the post of schoolmistress

in the village of Little Woolston, Buckinghamshire where she

taught the sons of the local farm workers to read. In

November 1862 she took a holiday at Coatham near

Middlesbrough to recuperate from an illness. While there she

bumped into James, who again proposed, and she accepted. But

the marriage was not to be because of a hostile reaction

from his family.

During the following year she returned

to Coatham to look after her sister Frances who was

recovering from a nervous breakdown. While there she saw the

work of the Sisters of the Good Samaritan Order and was

greatly impressed. The sisters’ lives were devoted to strict

religious observance, and charitable work, the things she

aspired to, mainly because of her brothers’ influence and

his work with the Oxford Movement.

Her sister Frances joined the order,

and one year later, in September 1864 so did Dorothy. She

took the name Sister Dora. The sisters’ duties included

nursing patients in the Cottage Hospital at Coatham, and the

Cottage Hospital at Walsall. One of Sister Dora’s heroes was

Florence Nightingale and so the idea of nursing the sick

must have greatly appealed to her.

Sister Dora’s nursing career began at

Coatham. Nursing was under the supervision of Sister Mary

Jacques who greatly influenced her, especially because she

had trained at Kaiserwerth Hospital in Germany, where

Florence Nightingale had worked. Sister Mary had been

working in the hospital at Walsall until she caught scarlet

fever and had to return to Coatham to convalesce. Sister

Dora was hurriedly sent as a temporary replacement, and

arrived at Walsall for the first time on 8th January, 1865.

After staying for two months she returned to Coatham, and in

November came back to Walsall, where she stayed for the rest

of her life.

|

|

Sister Dora and Sister Mary were

initially treated with suspicion, and even hostility by many

local people. At the time anti-Irish and anti-Catholic

feeling was rife in the town. Sister Dora soon caught

smallpox from an outpatient and was confined to her room, in

which the blinds were drawn. This led to a rumour that the

room was an oratory containing a figure of the Virgin Mary

wearing a crown. Stones and mud were thrown at the hospital

widows, but the dedicated sisters carried on caring for the

sick as usual. The hostility gradually faded as people came

to appreciate the sisters’ devotion to duty and their

difficult undertaking. They also worked in the community

visiting outpatients, some of whom were severely injured.

In 1866 she fell in love with a young

surgeon, possibly John Redfern Davies. They were soon

engaged, but this led to a dilemma, stress, and illness. He

was an atheist, and she knew that she would have to choose

between him, and her Christian beliefs, and charitable work.

She decided that she could not give-up her work and so the

engagement ended. She knew that she had badly let him down,

which resulted in illness from stress.

In 1867 the Sisterhood was

reconstituted into a proper religious order, and Sister Dora

was given the opportunity to take vows. Instead she decided

to stay in Walsall serving the local community, where her

true vocation lay.

|

From an old postcard. |

One of the reliefs on Sister Dora's

statue depicting the Pelsall mine disaster of 1872. |

In May 1868 when the new Cottage

Hospital opened she was in sole charge of all aspects of

nursing. She attended post mortems and dissections to learn

new skills, and set about making the hospital the best of

its kind in the country. She became an expert in the

treatment of lacerations, at setting fractures, and treating

eye injuries.

Other hospitals tried to tempt her away

by offering a higher salary, but she was not interested, her

devotion to duty came first.

The hospital’s new surgeon

James MacLachlan was greatly impressed with her and tried to

persuade her to train as a doctor, but Sister Dora’s

commitment to nursing, and desire to help others came first.

To give this up for several years whilst training as a

doctor was very much against her beliefs.

|

|

She looked after her patients extremely

well, and paid attention to the minutest details of their

care. She insisted on high standards of comfort and care,

rigorous cleanliness everywhere, and nutrition, supervising

each meal herself.

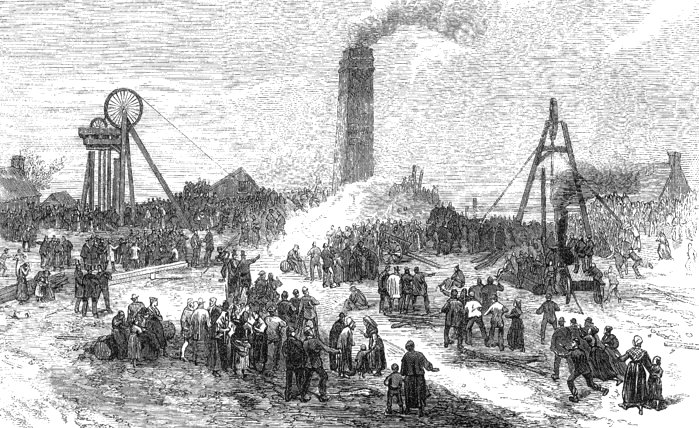

She is particularly remembered for her

valiant work and devotion to care after two serious

industrial accidents, and a smallpox epidemic. The first

accident happened at Pelsall Colliery on 14th November, 1872

when the pit rapidly flooded, trapping twenty two men and

boys underground for five days. Sadly they all died before

help could reach them, but Sister Dora lived with the

waiting relatives, distributed blankets and food at the

pithead, and did everything possible to support and comfort

them at that terrible time.

|

|

Pelsall Colliery. From The

Illustrated London News. |

| The employees of the London & North

Western Railway were so impressed with her efforts after the

accident that they subscribed fifty pounds out of their

wages (a substantial sum at the time) to present her with a

pony and trap. The presentation took place on 20th June,

1873. |

| In February 1875 a virulent smallpox

epidemic broke out in Walsall. Although the Epidemic

Hospital in Hospital Street, built in 1872, had all of the

necessary facilities, it gained a terrible reputation. Sufferers preferred to take their chances at home

rather than enter the hospital.

Sister Dora knew that the

only way to control the disease was to isolate the

sufferers, and so she moved into the Epidemic Hospital on

28th February and took charge. Her reputation was such that

people soon changed their mind and were convinced of the

benefits of entering the hospital.

She was assisted by two old women from the workhouse to

wash clothes and bedding and was visited daily by a doctor and the secretary from the

Cottage Hospital.

She stayed at the hospital for six months until August

1875 when the epidemic was over. |

Another of the reliefs on Sister

Dora's statue showing her caring for the sick. |

| The following is from a

letter that was sent by Sister Dora. It is

from D. C. Woods' book, 'A Documentary

History of Walsall and District in the

Nineteenth Century.'

My room is between the wards, with little

windows as you have, peeping into both. My

bed in one corner, chest of drawers, and

slip for my basin. The doctor said it 'smelt

of pox' this morning; and no wonder - they

were airing all the sheets by my fire when I

came in. I think the most infectious thing I

have to do is to nurse the babies, taking

them streaming out of their mothers' arms.

One has the pox on its arms and chest very

slightly. Our worst case is a lad of

eighteen. He vomits everything, and is so

delirious; he got out of his bed this

morning, and I thought he had escaped into

the town, but I found him in an empty ward.

All the patients are

alive but that is generally the case with

smallpox and dirty people. I could only

venture to wash their hands and faces in hot

water this morning. I have had to make

garments for my urchins today; it is very

difficult to get anything here. Everything

has to be ordered at the Town Council

office. I see -- - is timid! He kept a

respectful distance today from me and the

patients, but do not tell him I said so . .

. I am going to send a letter to the

patients, which you are to read to them, and

you must tell me what they say. As I read

the prayers this morning I saw the tears

roll down one woman's face, who I know is

living in sin with a man I have nursed.

There is not one case in who does not know

me.

One of the police came

to see me to-day, and he said they declared

in the town they should not mind having the

smallpox with 'Sister' to nurse them. I

declare I taste it in my tea. I have made my

room look as respectable as I can . . . . Is

not this a glorious retreat for me in Lent?

I can have no idle chatter. |

|

The relief on the statue which depicts

the Birchills furnace explosion. There is no evidence to

suggest that she actually went to the scene of the

explosion. |

The second industrial accident for

which she is remembered took place on 15th October, 1875 at

Birchills Iron Works.

A blast furnace exploded as it was

being tapped, when a tuyère

burst. The furnace workers were covered with molten metal and red hot ashes.

Three men died instantly, and twelve others, all with

serious burns were rushed to the Cottage Hospital.

Sister

Dora immediately took charge of the men and treated them

alone, shutting herself up in their side ward, nursing them

both day and night for several weeks. Despite all of her

efforts, ten of them died from their terrible injuries.

At the time burns would often be

infected and were difficult to treat. The men’s presence,

and their infected wounds had infected the whole hospital

with erysipelas, which meant that the wounds of new patients

would also be infected. Contemporary medicine offered no

solution, the only option was to close the hospital.

|

| |

|

| Read a contemporary account

of the Birchills explosion |

|

| |

|

|

The Sisters of the Good Samaritan Order

wanted Sister Dora to move elsewhere, but she refused. When

asked why, she replied "I am a woman not a piece of

furniture!" Around this time she severed her formal

links with the Sisterhood, but retained the name Sister

Dora.

While a new hospital was built, a

temporary hospital opened in a house in Bridgeman Place,

owned by the London & North Western Railway. It

was far from ideal, only having ten beds on four floors.

There was little space, and not even enough room to

manoeuvre a stretcher between floors. Patients (alive or

dead) had to be carried, usually by Sister Dora herself.

Because of the lack of space many people had to be treated

as outpatients. In 1877 over 15,000 people were treated in

this way, usually by Sister Dora. The hospital was close to

the railway and so patients were continually disturbed by

passing trains.

The house was far from suitable for use

as a hospital. In 1878 it became infected with typhoid fever

and had to be closed.

Sister Dora refused the honour of

laying the foundation stone for the new hospital, but was

deeply involved in planning the new building, continually

suggesting amendments to the plans.

During 1877 she began to suffer from

exhaustion. This gradually worsened and so she consulted two

doctors who both confirmed that she was suffering from

breast cancer. Although a mastectomy was a possibility, the

procedure had not been fully mastered, and often left the

patient an invalid. Because of this it was seldom carried

out.

|

|

She decided to carry on with her work,

in the certainty that she only had a short time to live. She

kept the disease secret and decided to treat it herself.

After the hospital closed, Sister Dora visited London and

Paris. While in London she attended operations conducted by

the surgeon Joseph Lister, a pioneer of antiseptic surgery.

She quickly realised its benefits and ensured that the new

hospital would have the necessary equipment.

In September her health deteriorated. She returned to

Walsall to inspect the building work, but felt too ill to

look for lodgings. She returned to a hotel in Birmingham

where she collapsed. She was given two weeks to live, and

greatly wanted to return to Walsall so that she could die

amongst her own people.

The hospital committee

rented a small house for her in Wednesbury Road, where she

arrived on 8th October. She was in constant pain, and found

it difficult to breath, and couldn’t take solid food.

|

The final relief showing her caring

for children. |

|

It had been hoped that she could

perform the opening ceremony when the new hospital opened on

4th November. Unfortunately she was too ill to be there. She suffered for three months. The end

finally came on December 24th. She asked friends and

colleagues to leave her bedside saying “I have lived alone,

let me die alone.” The end finally came at 2 p.m.

Her funeral took place on Saturday 28th December. She had

wanted a quiet affair, but it was not to be. The coffin was carried to Queen Street Cemetery by

eighteen railway workers, and watched by large crowds who

came to pay their last respects.

The crowd delayed the long procession from

the Cottage Hospital. It included members of the police

force, choristers and senior choir members, physicians and

surgeons, clergy and ministers, mourners, the executor

James Slater, the executive committee, the Mayor and

Councillors, representatives of the press, the Governors of

Queen Mary’s School, the Guardians of the School Board, old

patients, and many others. The funeral was an elaborate

affair. Sister Dora had chosen the words for her headstone

herself. It simply reads:

In memory

of Sister Dora who entered into rest on Christmas Eve 1878

She is remembered by a stained glass

window in St. Matthew’s Church, and the statue on The

Bridge. It was paid for by public subscription. The

collection began in 1879, and the statue was unveiled on

Monday 11th October, 1886. The unveiling ceremony was a

civic affair, with a long procession starting at the

hospital. Most of the town came to watch.

|

|

A memorial card for Sister Dora. Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore. |

|

Sister Dora's marble statue on

The Bridge, was replaced with a bronze replica in 1957, as

can be seen from the newspaper article on the left,

dated 2nd January, 1957. |

Sister Dora's statue in the mid 1970s.

Taken by Richard Ashmore. Courtesy of John & Christine Ashmore. |

| Even though she

died over 130 years ago, she is still remembered by most

people for her outstanding work and devotion to duty. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|