|

Extracts from

Dr. J .H. Stallard's report on Walsall Workhouse.

Published in The Lancet. November 9th,

1867

The male tramp ward is a narrow

barn-like building, only eight feet wide. Within it

is something like a hound kennel, though neither

half so clean or comfortable. It is paved with rough

brick, and there is a small window for ventilation

at the side. There are two wooden shelves across the

end, one above the other; the lower is three feet,

the other six feet from the ground, and on them the

unfortunate vagrants are supposed to sleep, under

cover of a dirty rug. The only accommodation is a

filthy-looking iron bucket sprinkled with carbolic

acid, and enclosed by the present master in a wooden

box. This ward, in the opinion of the medical

officer, is fitted to contain seven inmates, but the

average is much more, and on several occasions

twenty seven tramps have been locked in, without

food or light, or any means of communication with

the officers outside. Imagination cannot picture the

fearful pandemonium on such occasions, and we cannot

trust ourselves to comment on the continuance of

such a gross enormity for twenty years.

In the interval between these

two reports we find no hint recorded of imperfection

or complaint. When the yards were unpaved and the

privies had stinking cesspits; when the sick were

compelled to go to the receiving wards to get a

bath, and were scattered about the house, far

removed from their nurses; when the supply of linen

barely sufficed to afford a pair of sheets for every

bedstead, or a change for every inmate; when there

was not a cupboard in the wards, and the general

storeroom was not larger than a closet, the state of

the workhouse was still "reported satisfactory”.

No attention appears to have

been directed to the fact that sickness and

infirmity had completely occupied the place of

idleness, and that the workhouse from having been

the refuge of destitution and the lodging of

vagabonds, had become an infirmary for sick almost

from top to bottom. Not withstanding the change of

inmates, "the workhouse test" must be maintained,

and no deviation from the rules or dietary was or is

willingly permitted. Even the poor old women may not

smuggle in a teapot to make themselves a quiet cup

of tea; they must be contented with the workhouse

slops, which if anyone desire to try, let him pour

fourteen imperial pints of boiling water on an ounce

of tea at 1s. 8d. per lb., add 5 oz. of moist sugar,

and a little skim milk, and taste it if he can.

But the local authorities have

kindly hearts; they wink at the women's smuggled

teapot, and give tobacco to the men; they have made

the wards look cheerful; they have polished the

floors and painted the walls; they have put matting

between the beds and curtains to the windows, and,

at the instigation chiefly of the master and the

surgeon, they have attended to a variety of minor

matters, which show that more still would have been

done if only they had known how to do it.

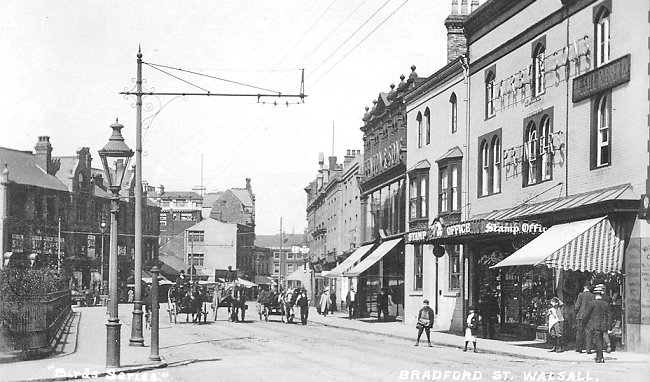

From an old postcard.

Throughout the entire

establishment there is but a single wash handbasin,

and it was a mystery to the master how it came

there. The bedridden, the fever-stricken, the

venereal, the infected with itch, and the

convalescent, nay, even the infants in the nursery,

are washed in dirty-looking wooden buckets. Two

towels a week are given to a ward of ten patients;

and there are neither combs nor brushes given out to

any throughout the house. So little are the

essentials of cleanliness attended to that the male

nurse has but a single iron basin, which is used to

wash all wounds alike, to make poultices, and for

every office for which a basin is required.

The tidy appearance of the

wards is equally superficial and deceptive. The male

infirmary consists of seven wards, which are for the

most part 17ft. wide, and 9ft. or 10ft. high, with

opposite windows. They look light and clean. But the

beds are so close together that another could not

anywhere be placed, and there is scarcely space to

walk between them. There is, therefore, no room for

lockers. The ventilation is throughout defective,

and the water closets (where there are any) open

directly upon the wards. They are universally small

and badly ventilated, and stink abominably.

The fever ward contains 3978

cubic feet, and has nine beds. It is, therefore more

than twice too crowded. The classification is most

extraordinary, and shows the unfitness and

inadequacy of the building in the strongest light.

The female infirmaries, though

scrupulously clean and tidy looking, are even worse

than the male in all essential points. The wards are

generally crammed to the full with beds, the

ventilation is defective, and the water closets

equally objectionably, and even more unclean. An

acute case had just been admitted into No. 1 ward

from the school. The presence of four epileptics

would scarcely conduce to her quiet or recovery. As

there are no special wards, the imbeciles are

distributed amongst the sick and bedridden; a most

improper arrangement, which cannot be too strongly

condemned.

Before concluding, it is

necessary to make a few observations on the

condition of the children, a considerable number of

whom are confined in a separate ward on account of

skin disease. The schoolroom appeared to us close

and overcrowded, and both playgrounds are reported

by the surgeon damp and insufficient. The boys’

bedroom is also overcrowded. As there is no garden,

green vegetables are only exceptionally provided.

These circumstances would seem to account for the

obstinacy of skin complaints, and should be remedied

at once. If this be impossible, let the guardians

break up the school and distribute the children in

the villages around on the Scotch plan. They would

thus relieve their overcrowded house, and avoid the

necessity of the proposed extension.

In conclusion, the Walsall

Workhouse presents an example of cleanliness and

order calculated to deceive a superficial observer.

A closer inspection, however, reveals the absence of

all essentials for the proper treatment of the sick.

The wards are ill furnished, overcrowded, and for

the most part unfitted for their purpose. The

ventilation is defective and ill arranged. The

stinking closets open upon the wards, many of which

are not provided for at all. There are no baths, no

day rooms, and no airing ground. There is a shameful

deficiency of lavatories and washing apparatus.

There is no classification of the patients, who are

necessarily disturbed by imbeciles and epileptics.

There are no night nurses, and not sufficient paid

assistance to secure attention to so large a number,

the master being overwhelmed with accounts and other

duty. The surgeon is ill-paid, and the dispensing

arrangements are unsatisfactory in the extreme.

Indeed, we can only wonder that anyone could have

visited the wards without discovering causes of

complaint. |